Полная версия

Полная версияDiary in America, Series One

The cattle-show took place when I was at Lexington. That of horned beasts I was too late for; but the second day I went to the exhibition of thorough-bred horses. The premiums were for the best two-year old, yearlings, and colts, and many of them were very fine animals. The third day was for the exhibition of mules; which, on account of size there being a great desideratum, are bred only from mares; the full-grown averaged from fifteen to sixteen hands high, but they have often been known to be seventeen hands high. I had seen them quite as large in a nobleman’s carriage in the south of Spain; but then they were considered rare, and of great value. After all the other varieties of age had made their appearance, and the judges had given their decision, the mules foaled down this year were to be examined. As they were still sucking, it was necessary that the brood mares should be led into the enclosed paddock, where the animals were inspected, that the foals might be induced to follow; as soon as they were all in the enclosure the mares were sent out, leaving all the foals by themselves. At first they commenced a concert of wailing after their mothers, and then turned their lamentations into indignation and revenge upon each other. Such a ridiculous scene of kicking took place as I never before witnessed, about thirty of them being most sedulously engaged in the occupation, all at the same time. I never saw such ill-behaved mules; it was quite impossible for the judges to decide upon the prize, for you could see nothing but heels in the air; it was rap, rap, rap, incessantly against one another’s sides, until they were all turned out, and the show was over. I rather think the prize must, in this instance, have been awarded to the one that kicked highest.

The fourth day was for the exhibition of jackasses, of two-year and one-year, and for foals, and jennies also; this sight was to me one of peculiar interest. Accustomed as we are in England to value a jackass at thirty shillings, we look down upon them with contempt; but here the case is reversed: you look up at them with surprise and admiration. Several were shown standing fifteen hands high, with head and ears in proportion; the breed has been obtained from the Maltese jackass, crossed by those of Spain and the south of France. Those imported seldom average more than fourteen hands high; but the Kentuckians, by great attention and care, have raised them up to fifteen hands, and sometimes even to sixteen.

But the price paid for these splendid animals, for such they really were, will prove how much they are in request. Warrior, a jackass of great celebrity, sold for 5,000 dollars, upwards of 1,000 pounds sterling. Half of another jackass, Benjamin by name, was sold for 2,500 dollars. At the show I asked a gentleman what he wanted for a very beautiful female ass, only one year old; he said that he could have 1,000 dollars, 250 pounds for her, but that he had refused that sum. For a two-year old jack, shown during the exhibition, they asked 3000 dollars, more than 600 pounds. I never felt such respect for donkeys before; but the fact is, that mule-breeding is so lucrative, that there is no price which a very large donkey will not command.

I afterwards went to a cattle sale a few miles out of the town. Don Juan, a two-year old bull, Durham breed, fetched 1,075 dollars; an imported Durham cow, with her calf, 985 dollars. Before I arrived, a bull and cow fetched 1,300 dollars each of them, about 280 pounds. The cause of this is, that the demand for good stock, now that the Western States are filling up, becomes so great that they cannot be produced fast enough. Mr Clay, who resides near Lexington, is one of the best breeders in the State, which is much indebted to him for the fine stock which he has imported from England.

Another sale took place, which I attended, and I quote the prices:– Yearling bull, 1,000 dollars; ditto heifer, 1,500. Cows, of full Durham blood, but bred in Kentucky, 1,245 dollars; ditto, 1,235 dollars. Imported cow and calf, 2,100 dollars.

It must be considered, that although a good Durham cow will not cost more than twenty guineas perhaps, in England, the expenses of transport are very great, and they generally stand it to the importers, about 600 dollars, before they arrive at the State of Kentucky.

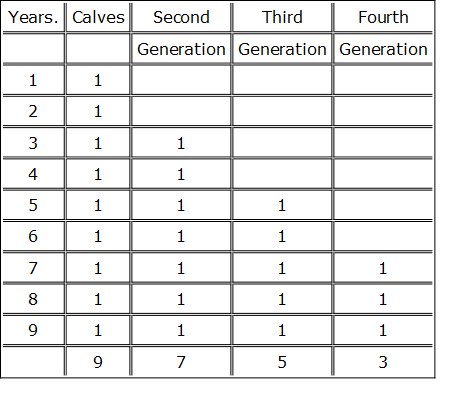

But to prove that the Kentuckians are fully justified in giving the prices they do, I will shew what was the profit made upon an old cow before she was sold for 400 dollars. I had a statement from her proprietor, who had her in his possession for nine years. She was a full-bred cow, and during the time that he had held her in his possession, she had cleared him 15,000 dollars by the sale of her progeny: As follows:—

averaging 625 dollars a head, which is by no means a large price, as the two cows, which sold at the sale for 1,245, and 1,235 dollars, were a part of her issue.

Lexington is a very pretty town, with very pleasant society, and afforded me great relief after the unpleasant sojourn I had had at Louisville. Conversing one day with Mr Clay, I had another instance given me of the mischief which the conduct of Miss Martineau has entailed upon all those English who may happen to visit America. Mr Clay observed that Miss Martineau had remained with him for some time, and that during her stay, she had professed very different, or at least more modified opinions on the subject of slavery, than those she has expressed in her book: so much so, that one day, having read a letter from Boston cautioning her against being cajoled by the hospitality and pleasant society of the Western States, she handed it to him, saying, “They want to make a regular abolitionist of me.” “When her work came out,” continued Mr Clay, “although I read but very little of it, I turned to this subject so important with us, and I must say I was a little surprised to find that she had so changed her opinions.” The fact is, Miss Martineau appears to have been what the Kentuckians call, “playing ’possum.” I have met with some of the Southern ladies whose conversations on slavery are said, or supposed, to have been those printed by Miss Martineau, and they deny that they are correct. That the Southern ladies are very apt to express great horror at living too long a time at the plantations, is very certain; not, however, because they expect to be murdered in their beds by the slaves, as they tell their husbands, but because they are anxious to spend more of their time at the cities, where they can enjoy more luxury and amusement than can be procured at the plantations.

Every body rides in Virginia and Kentucky, master, man, woman, and slave, and they all ride well: it is quite as common to meet a woman on horseback as a man, and it is a pretty sight in their States to walk by the Church doors and see them all arrive. The Churches have stables, or rather sheds, built close to them, for the accommodation of the cattle.

Elopements in these States are all made on horseback. The goal to be obtained is to cross to the other side of the Ohio. The consequence is that it is a regular steeple-chase; the young couple clearing everything, father and brothers following. Whether it is that, having the choice, the young people are the best mounted, I know not, but the runaways are seldom overtaken. One couple crossed the Ohio when I was at Cincinnati, and had just time to tie the noose before their pursuers arrived.

At Lexington, on Sunday, there is not a carriage or horse to be obtained by a white man for any consideration, they having all been regularly engaged for that day by the negro slaves, who go out in every direction. Where they get the money I do not know; but certain it is, that it is always produced when required. I was waiting at the counter of a sort of pastry-cook’s, when three negro lads, about twelve or fourteen years old, came in, and, in a most authoritative tone, ordered three glasses of soda-water.

Returned to Louisville.

Volume Two—Chapter Fourteen

There is one great inconvenience in American travelling, arising from the uncertainty of river navigation. Excepting the Lower Mississippi and the Hudson, and not always the latter, the communication by water is obstructed during a considerable portion of the year, by ice in the winter, or a deficiency of water in the dry season. This has been a remarkable season for heat and drought; and thousands of people remain in the States of Ohio, Virginia, and Kentucky, who are most anxious to return home. It must be understood, that during the unhealthy season in the southern States on the Mississippi, the planters, cotton-growers, slave holders, store-keepers, and indeed almost every class, excepting the slaves and overseers, migrate to the northward, to escape the yellow fever, and spend a portion of their gains in amusement.

They go to Cincinnati and the towns of Ohio, to the Lakes occasionally, but principally to the cities and watering places of Virginia and Kentucky, more especially Louisville, where I now am; and Louisville, being also the sort of general rendezvous for departure south, is now crammed with southern people. The steam boats cannot run, for the river is almost dry; and I (as well as others) have been detained much longer on the banks of the Ohio than was my intention. There is land-carriage certainly, but the heat of the weather is so overpowering that even the Southerns dread it; and in consequence of this extreme heat the sickness in these western States has been much greater than usual. Even Kentucky, especially that part which borders on the Mississippi, which, generally speaking, is healthy, is now suffering under malignant fevers. I may here remark, that the two States, Illinois and Indiana, and the western portions of Kentucky and Tennessee, are very unhealthy; not a year passes without a great mortality from the bilious congestive fever, a variety of the yellow fever, and the ague; more especially Illinois and Indiana, with the western portion of Ohio, which is equally flat with the other two States. The two States of Indiana and Illinois lie, as it were, at the bottom of the western basin; the soil is wonderfully rich, but the drainage is insufficient, as may be seen from the sluggishness with which these rivers flow. Many and many thousands of poor Irish emigrants, and settlers also, have been struck down by disease, never to rise again, in these rich but unhealthy States; to which, stimulated by the works published by land-speculators, thousands and thousands every year repair, and, notwithstanding the annual expenditure of life, rapidly increase the population. I had made up my mind to travel by land-carriage to St. Louis, Missouri, through the States of Indiana and Illinois, but two American gentlemen, who had just arrived by that route, succeeded in dissuading me. They had come over on horseback. They described the disease and mortality as dreadful. That sometimes, when they wished to put up their horses at seven or eight o’clock in the evening, they were compelled to travel on till twelve or one o’clock before they could gain admittance, some portion in every house suffering under the bilious fever, tertian ague, or flux. They described the scene as quite appalling. At some houses there was not one person able to rise and attend upon the others; all were dying or dead and to increase the misery of their situations, the springs had dried up, and in many places they could not procure water except by sending many miles. A friend of mine, who had been on a mission through the portion of Kentucky and Tennessee bordering on them Mississippi, made a very similar statement. He was not refused to remain where he stopped, but he could procure no assistance, and everywhere ran the risk of contagion. He said that some of the people were obliged to send their negroes with a waggon upwards of fifteen miles to wash their clothes.

That this has been a very unhealthy season is certain, but still, from all the information I could obtain, there is a great mortality every year in the districts I have pointed out; and such indeed must be the case, from the miasma created every fall of the year in these rich alluvial soils, some portions of which have been worked for fifty years without the assistance of manure, and still yield abundant crops. It will be a long while before the drainage necessary to render them healthy can be accomplished. The sickly appearance of the inhabitants establishes but too well the facts related to me; and yet, strange to say, it would appear to be a provision of Providence, that a remarkable fecundity on the part of the women in the more healthy portions of their Western States, should meet the annual expenditure of life. Three children at a birth are more common here than twins are in England; and they, generally speaking, are all reared up. There have been many instances of even four.

The western valley of America, of which the Mississippi may be considered as the common drain, must, from the surprising depth of the alluvial soil, have been (ages back) wholly under water, and, perhaps, by some convulsion raised up. What insects are we in our own estimation when we meditate upon such stupendous changes.

Since I have been in these States, I have been surprised at the stream of emigration which appears to flow from North Carolina to Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri. Every hour you meet with a caravan of emigrants from that sterile but healthy state. Every night the banks of the Ohio are lighted up with their fires, where they have bivouacked previously to crossing the river; but they are not like the poor German or Irish settlers: they are well prepared, and have nothing to do, apparently, but to sit down upon their land. These caravans consist of two or three covered wagons, full of women and children, furniture, and other necessaries, each drawn by a team of horses; brood mares, with foals by their sides, following; half a dozen or more cows, flanked on each side by the men, with their long rifles on their shoulders; sometimes a boy or two, or a half-grown girl on horseback. Occasionally they wear an appearance of more refinement and cultivation, as well as wealth, the principals travelling in a sort of worn-out old carriage, the remains of the competence of former days.

I often surmised, as they travelled cheerfully along, saluting me as they passed by, whether they would not repent their decision, and sigh for their pine barrens and heath, after they had discovered that with fertility they had to encounter such disease and mortality.

I have often heard it asserted by Englishmen, that America has no coal. There never was a greater mistake: she has an abundance, and of the very finest that ever was seen. At Wheeling and Pittsburg, and on all the borders of the Ohio river above Guyandotte, they have an inexhaustible supply, equal to the very best offered to the London market. All the spurs of the Alleghany range appear to be one mass of coal. In the Eastern States the coal is of a different quality, although there is some very tolerable. The anthracite is bad, throwing out a strong sulphureous gas. The fact is that wood is at present cheaper than coal, and therefore the latter is not in demand. An American told me one day, that a company had been working a coal mine in an Eastern State, which proved to be of a very bad quality; they had sent some to an influential person as a present, requesting him to give his opinion of it, as that would be important to them. After a certain time he forwarded to them a certificate couched in such terms as these:– “I do hereby certify that I have tried the coal sent me by the company at —, and it is my decided opinion, that when the general conflagration of the world shall take place, any man who will take his position on that coal-mine will certainly be the last man who will be burnt.”

I had to travel by coach for six days and nights, to arrive at Baltimore. As it may be supposed, I was not a little tired before my journey was half over; I therefore was glad when the coach stopped for a few hours, to throw off my coat, and lie down on a bed. At one town, where I had stopped, I had been reposing more than two hours when my door was opened—but this was too common a circumstance for me to think any thing of it; the people would come into my room whether I was in bed or out of bed, dressed or not dressed, and if I expostulated, they would reply, “Never mind, we don’t care, Captain.” On this occasion I called out, “Well, what do you want?”

“Are you Captain M—?” said the person walking up to the bed where I was lying.

“Yes, I am,” replied I.

“Well, I reckon I wouldn’t allow you to go through our town without seeing you any how. Of all the humans, you’re the one I most wish to see.”

I told him I was highly flattered.

“Well now,” said he, giving a jump, and coming down right upon the bed in his great coat, “I’ll just tell you; I said to the chap at the bar, ‘Ain’t the Captain in your house?’ ‘Yes,’ says he. ‘Then where is he?’ says I. ‘Oh,’ says he, ‘he’s gone into his own room, and locked himself up; he’s a d—d aristocrat, and won’t drink at the bar with other gentlemen.’ So, thought I, I’ve read M—’s works, and I’ll be swamped if he is an aristocrat, and by the ’tarnal I’ll go up and see; so here I am, and you’re no aristocrat.”

“I should think not,” replied I, moving my feet away, which he was half sitting on.

“Oh, don’t move; never mind me, Captain, I’m quite comfortable. And how do you find yourself by this time?”

“Very tired indeed,” replied I.

“I suspicion as much. Now, d’ye see, I left four or five good fellows down below who wish to see you; I said I’d go up first, and come down to them. The fact is, Captain, we don’t like you should pass through our town without showing you a little American hospitality.”

So saying, he slid off the bed, and went out of the room. In a minute he returned, bringing with him four or five others, all of whom he introduced by name, and reseated himself on my bed, while the others took chairs.

“Now, gentlemen,” said he, “as I was telling the Captain, we wish to show him a little American hospitality; what shall it be, gentlemen; what d’ye say—a bottle of Madeira?”

An immediate answer not being returned, he continued:

“Yes, gentlemen, a bottle of Madeira; at my expense, gentlemen, recollect that; now ring the bell.”

“I shall be most happy to take a glass of wine with you,” observed I, “but in my own room the wine must be at my expense.”

“At your expense, Captain; well, if it must be, I don’t care; at your expense then, Captain, if you say so; only, you see, we must show you a little American hospitality, as I said to them all down below; didn’t I, gentlemen?”

The wine was ordered, and it ended in my hospitable friends drinking three bottles, and then they all shook hands with me, declaring how happy they should be if I came to the town again, allowed them to show me a little more American hospitality.

There was something so very ridiculous in this event, that I cannot help narrating it; but let it not be supposed, for a moment, that I intend it as a sarcasm upon American hospitality in general. There certainly are conditions usually attached to their hospitality, if you wish to profit by it to any extent; and one is, that you do not venture to find fault with themselves, their manners, or their institutions.

Note—That a guest, partaking of their hospitality, should give his opinions unasked, and find fault, would be in very bad taste, to say the least of it. But the fault in America is, that you are compelled to give an opinion, and you cannot escape by a doubtful reply: as the American said to me in Philadelphia, “I wish a categorical answer.” Thus, should you not agree with them, you are placed upon the horns of a dilemma: either you must affront the company, or sacrifice truth.

End of DiaryVolume Three—Chapter One

Remarks—LanguageThe Americans boldly assert that they speak better English than we do, and I was rather surprised not to find a statistical table to that effect in Mr Carey’s publication. What I believe the Americans would imply by the above assertion is that you may travel through all the United States and find less difficulty in understanding or being understood, than in some of the counties of England, such as Cornwall, Devonshire, Lancashire and Suffolk. So far they are correct; but it is remarkable how very debased the language has become in a short period in America. There are few provincial dialects in England much less intelligible than the following. A Yankee girl, who wished to hire herself out, was asked if the had any followers or sweethearts? After a little hesitation, she replied, “Well, now, can’t exactly say; I bees a sorter courted and a sorter not; reckon more a sorter yes than a sorter no.” In many points the Americans have to a certain degree obtained that equality which they profess; and, as respects their language, it certainly is the case. If their lower classes are more intelligible than ours, it is equally true that the higher classes do not speak the language so purely or so classically as it is spoken among the well educated English. The peculiar dialect of the English counties is kept up because we are a settled country; the people who are born in a county live in it, and die in it, transmitting their sites of labour or of amusement to their descendants, generation after generation, without change: consequently, the provincialisms of the language become equally hereditary. Now, in America, they have a dictionary containing many thousands of words, which, with us, are either obsolete or are provincialisms, or are words necessarily invented by the Americans. When the people of England emigrated to the states, they came from every county in England, and each county brought its provincialisms with it. These were admitted into the general stock; and were since all collected and bound up by one Mr Webster. With the exception of a few words coined for local uses (such as snags and sawyers, on the Mississippi,) I do not recollect a word which I have not traced to be either a provincialism of some English county, or else to be obsolete English. There are a few from the Dutch, such as stoup, for the porch of a door, etcetera. I was once talking with an American about Webster’s dictionary, and he observed, “Well now, sir, I understand it’s the only one used in the Court of St. James, by the king, queen, and princesses, and that by royal order.”

The upper class of the Americans do not, however, speak or pronounce English according to our standard; they appear to have no exact rule to guide them, probably from the want of any intimate knowledge of Greek or Latin. You seldom hear a derivation from the Greek pronounced correctly, the accent being generally laid upon the wrong syllable. In fact, every one appears to be independent, and pronounces just as he pleases.

But it is not for me to decide the very momentous question, as to which nation speaks the best English. The Americans generally improve upon the inventions of others; probably they may have improved upon our language.

I recollect some one observing how very superior the German language was to the English, from their possessing so many compound substantives and adjectives; whereupon his friend replied, that it was just as easy for us to possess them in England if we pleased, and gave us as an example an observation made by his old dame at Eaton, who declared that young Paulet was, without any exception, the most good-for-nothing-est, the most provoking-people-est, and the most poke-about-every-corner-est boy she had ever had charge of in her life.

Assuming this principle of improvement to be correct, it must be acknowledged that the Americans have added considerably to our dictionary; but, as I have before observed, this being a point of too much delicacy for me to decide upon, I shall just submit to the reader the occasional variations, or improvements, as they may be, which met my ears during my residence in America, as also the idiomatic peculiarities, and having so done, I must leave him to decide for himself.

I recollect once talking with one of the first men in America, who was narrating to me the advantages which might have accrued to him if he had followed up a certain speculation, when he said, “Sir, if I had done so, I should not only have doubled and trebled, but I should have fourbled and fivebled my money.”