Полная версия:

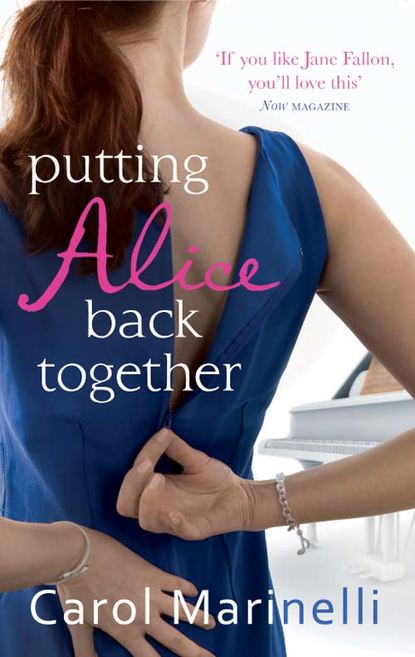

Putting Alice Back Together

I headed back out there, scorching with shame but trying to act as if nothing just happened.

‘Where did you get to?’ Roz asked, but she didn’t wait for my answer. ‘Are you coming out for a cigarette?’

Nicole was enjoying herself. Christopher, having ordered more champagne for the group, was saying goodbye, though he didn’t extend a farewell to me.

‘Have a great night, Nicole.’ He kissed her on the cheek and she smiled back at him.

‘Thanks for coming.’

Only then did he smirk in my direction. ‘It was no trouble at all.’

I stood outside with Roz and I didn’t have a cigarette, I just breathed in the cool night air and tried not to think about what I’d just done.

‘I can’t believe she’s going into work tomorrow…’ Roz was chatting away. ‘She’s flying tomorrow night…’

‘That’s Nic.’ I went into my bag for my cigarettes and I pulled out the appointment card too.

‘I’ll come back to the flat with you after work and we can all—’

‘Actually…’ I hesitated. I didn’t really know how to tell Roz. ‘I’m leaving work a bit early tomorrow, I’ve got an appointment.’ I knew she was curious, that she was waiting for me to explain, but I didn’t and Roz would never push. ‘I’ll be back in time to pick up Nic. You can meet me back at the flat.’

‘That’s fine,’ Roz said. ‘I’ll just meet you at the airport.’

I’d been intending to cancel.

Or just not show up.

I had no intention of examining my past, but I needed a prescription and, I reluctantly admitted, perhaps I should speak to someone—not about it, of course, but about other things.

Maybe this Lisa could help.

Three

Another Alice

I liked the piano. It was my first instrument, the violin my second, but it was the piano I loved.

I hated the lessons, but I sort of understood I had to have them.

Young Mozart I was not—but I could read music.

I just could.

To me, it was easier than learning to read English—a quaver was an eighth of a whole, that dot meant you lengthened the note.

I supposed I had not talent as such but, as my mother would tell everyone she met, her youngest daughter had an ‘ear for music’.

I lived and breathed music—the classics, hymns, anything I heard I wanted to play.

And as a teenager it had been considered nerdy.

Seriously nerdy.

Especially as I’d also sung in the church choir.

Of course I’d got teased at school and hated it when people found out about my other life, but I loved hymns and singing and a couple of times I even played the organ.

Yep—a serious nerd.

There’s nobody musical in my family. Mum’s a nurse, dad’s in sales and marketing, Eleanor is my oldest sister and basically does nothing apart from look good—well, she has to, she’s married to a cosmetic dentist. Then there’s Bonny the middle one, who takes after Mum and is a nurse too. It really took a lot of convincing from my teachers for Mum to realise that she wasn’t being ripped off when the school suggested that if I wanted to pursue a career in music, then I needed some extra private tuition. (I was fifteen then. Dad and Mum had just broken up so it caused a few rows, Dad said he was paying Mum plenty—Mum said… well, plenty.)

So, with things a bit tight, instead of more lessons with my regular music teacher, Mum found various students from a school of music to coach me. I was doing fairly well and looking at a career in teaching. As well as lessons and choir and choir practice, I had to practise my instruments for hours every day—though I didn’t mind practising the piano. In fact, I lived for it. It was the lessons I hated.

Still, as I said, I understood that I had to have them and just put up with them, I suppose…

Till Bonny’s wedding loomed, when everything changed.

As far as I can remember, Eleanor’s wedding just seemed to happen without fuss. I was ten and, along with Bonny, I was a bridesmaid, but I don’t remember the whole world stopping in preparation for Eleanor’s big day—I just remember the church and the party afterwards.

Oh, and the gleaming teeth in the photos.

One minute Eleanor was dating Noel and the next we were in the church, or so it had seemed.

Whereas Bonny’s wedding was the full circus.

Bonny’s life was a full circus, but the wedding and the preparation were the worst.

It was to be a New Year’s Eve wedding—it was the only way Lex’s relatives could all get over for it, and Mum, devastated that her middle child would be moving to Australia as soon as she took her final nursing exams, would do anything to please and appease. And, as much as I love Bonny, boy, did she take full advantage of the situation.

I was seventeen and full of teenage angst and wondering if I’d ever lose my virginity, especially since I’d never even been kissed. I was heavily in love with Gus, my latest music tutor, and I was also very aware that I was behind on piano practice and my exams were just a few months away. Which sounds ages, but it really wasn’t.

Not that any of this mattered to Bonny.

Lex, Bonny’s fiancé, was a sexy six-foot-three Australian who worked for some international pharmaceutical company and was helping to compile statistics both here and in America. They had met at the hospital Bonny worked at, had fallen in love and within three months had got engaged.

Everyone said Bonny was too young to marry, but Lex refused anything less. He didn’t want to live with her—if she was going to take the leap and move to Australia, then it would be as his wife.

He’s a nice guy, Lex.

A really nice guy, and even if Bonny was a bit young, I could understand why she didn’t want to let him go.

I had a crush on him—of course I did—I had a crush on everyone!

Bonny went a touch crazy in the weeks before the wedding: it was colour schemes and flowers and cakes and invitations. The whole house was wedding central. I couldn’t practise my violin or piano for two weeks before the big day. Really, I didn’t mind missing the violin, I could make up the time later, but I don’t think I’d ever been even two days without playing the piano. I didn’t just practise… I played. If I was tired, if I was depressed, if I’d been teased, if I’d had a shit day, I’d play. It didn’t lift me, instead it met me. I could just pour it out and hear how I was feeling.

Sometimes I glimpsed it—this zone, a place, like a gap that I stepped into and filled with a sound that was waiting to be made.

There’s no one else I can talk about it with, except for Gus—he gets it. Gus says that playing is a relief.

He’s right, that’s what it feels like sometimes—relief.

An energy that builds and it has to be let out somewhere.

It’s more than relief—it’s release.

Or it would be if it didn’t upset Bonny.

Everything upset Bonny.

Everything was done to appease her.

Which was why I had been forced to wear pink.

A sort of dusky pink, which was fashionable, my mum insisted—as if she would know. As if a size twenty, middle-aged woman with bad teeth and the beginnings of a moustache would know.

I hated it—I hated it so much, there was no way I was going to wear it. But my threats fell on deaf ears. It was Bonny’s Special Day—and what was a bit of public humiliation to a seventeen-year-old as long as the bride was smiling?

So I wrote reams of pages of ‘I hate Bonny’, ‘I want to kill Bonny’ and ‘I want to gouge out her eyes’ as I lay on my bed the afternoon before the wedding with the beastly pink dress hanging up in plastic on my wardrobe. I had my period and was having visions of flooding in the aisle, and to add to the joy, the hairdresser was here and, as anyone with frizzy red hair would understand, I wasn’t looking forward to that either.

I lay down and imagined that it was me getting married and not Bonny.

That sexy Lex only had eyes for me.

Then I felt bad—I mean, I might hate her but she is my sister—so I moved my fantasy over to Gus instead.

Except he was already married…

Apparently you couldn’t wash your hair on the day of the wedding, because the spectacular style Bonny had finally chosen after several screaming trips wouldn’t stay up on newly washed hair. So she was being blow-dried while I washed my hair and then the hairdresser would dry it with a diffuser and put in loads of product and then pin it up tomorrow. We’d had a practice a couple of weeks before and it had looked suitably disgusting but, again, I’d been told to shut up and not complain because it was Bonny’s Special Day.

So I washed my hair and I sat sulking in the kitchen as Bonny’s hair was being blow-dried, and then Eleanor’s was blow-dried too. Mum wasn’t having hers put up, so she was getting ‘done’ tomorrow, and as I moved to the stool, perhaps seeing my expression when the hairdresser took out her scissors, Mum tried to appease me. She couldn’t give a shag that I hated hairdressers and hated, hated, hated getting it trimmed—no, she just didn’t want me making a scene and upsetting Bonny.

‘It’s just a little trim,’ Mum warned, clucking around and trying to pour cold water on the cauldron of hate we were all sitting in before it exploded. ‘Oh, I didn’t tell you, I rang Gus and you can have an extra piano lesson,’ Mum said to my scowling face. ‘He’s working over the holiday break and he can fit you in on Monday.’

Now, that did appease me.

You see, Gus wasn’t like the usual, scurf-ridden, vegan tutors that Mum had found for me in the past. He was as sexy as hell, with brown dead-straight hair, no hint of dandruff and dark brown eyes that roamed over me for a little bit too long sometimes. He smelt fantastic too. Sometimes when he was leaning over me, or sitting beside while I played, I was scared to breathe because the scent of him made me want to turn around and just lick him! Like Lex, he was from Australia (they must make sexy men there—I was thinking of a gap year there to sample the delights). Gus spoke to me, instead of down to me. He spoke about real things, about his life, about me. Once when his moody bitch of a wife walked in on our lesson and reminded him that he’d gone over the hour, it came as a surprise to realise that we had. Instead of playing, for those last fifteen minutes we’d been talking and laughing and I felt a slight flurry in my stomach, because I knew that when I left there would be a row.

He started to tell me more and more about his problems with Celeste and I lapped every word up and then wrote it in my diary each night—analysing it, going over and over it, looking for clues, wishing I’d answered differently, wondering if I was mad to think that a man as sexy as Gus might somehow fancy me… but I felt that he did. He told me that he had intended that the sexy Celeste, who—and Gus and I giggled when he told me—played the cello, would be a fling. Well, she was now almost six months pregnant, his visa was about to expire, and he and Celeste would be going back to Melbourne once the baby was born—but for now he was broke and miserable and completely trapped. The sexy cello player he had dated was massive with child and the only thing, Gus had told me bitterly, that was between her legs these days was her head as she puked her way through pregnancy—not her cello, and certainly not him.

I loved Gus—he wasn’t like a teacher. And even though I knew Mum was paying him to be one, for that hour, once a week, I was more than his pupil. I was the sole focus of his attention—and I craved it.

He was so funny and sexy, and I couldn’t stand the thought of him going back to Melbourne, or even understand why the hell he put up with Celeste and her moods.

She was a bitch. She didn’t say hi to me, didn’t look up and say goodbye when the lesson was over. Occasionally she’d pop her head in and say something to Gus and look over me as if I were some pimply teenager, which of course I was. She thought she was so fucking gorgeous, wearing tight dresses and showing off her belly and massive boobs, but I knew how Gus bitched about her.

Actually, at our lesson yesterday he’d told me a joke. He knew I was as fed up with Bonny’s wedding as he had been with his and as I packed up my music sheets and loaded my bag and headed for the door, he called me back.

‘Hey, Alice.’ He smiled up at me from the piano stool. ‘Why does a bride smile on her wedding day?’

I could feel his dark eyes on my burning cheeks and I shrugged—I hate jokes, I never get them, oh, I pretend to laugh, but I never really get them.

‘I don’t know.’

‘Because she’s given her last blow job!’

I didn’t really get it. I laughed and said goodnight. I knew what a blow job was, sort of—I hadn’t even kissed a guy. I even told Bonny the joke when I got home but she wasn’t too impressed.

It was only that night as I lay in bed that I sort of got it, that I realised he was talking about Celeste.

I lay there feeling grown up—thought about Mandy Edwards and her snog with Scott, thought about Jacinta Reynolds and her fumble with Craig, a boy in lower sixth.

Gus was twenty-two.

It made me feel very grown up indeed.

Four

I was expecting offices. Nice, bland offices, but as I turned into the street I saw that it was a house, and better still there was a large sign that displayed to all and sundry that I was entering a psychologist’s practice.

Really. You’d think they’d be more discreet and write ‘Life Coaching’ or something.

A very bubbly receptionist greeted me and handed me a form to fill in. She told me to take a seat with the other psychopaths and social misfits and that Lisa would call me in soon.

God, I so did not belong here. There was a couple, sitting in stony silence, who were presumably here for marriage counselling (and from the way he rolled his eyes when she had the audacity to get up and get a drink from the water cooler, I didn’t fancy their chances much). Then there was a huge guy with a face like a bulldog who had probably been sent by the courts for anger management. There was, though, one fairly normal-looking guy, who was reading a magazine. He was rather good looking and he gave me a smile as he caught my eye, but I quickly looked away—I mean, normally I’d have been making conversation by now, but I had some standards, and refused to be chatted up in a psychologist’s waiting room. I mean, God alone knows what he was there for.

And what would you say when people asked where you met?

Mind you, I did feel guilty for snubbing him and when I saw him look at me again, I gave him a sort of sympathetic, understanding smile, just in case he was normal and was here for grief counselling. I started on the form and the disclaimers, telling them who my GP was, my job (er… why?) and filling in all the little boxes. I ticked my way merrily through the form—though it was completely unnecessary. What business of theirs was it where I worked? Or if I was at any risk of blood-borne diseases or had heart problems or had been involved in a workplace accident. I was here for a chat, not cardiac surgery. Mind you, I almost ticked ‘No’ to allergies, but quickly moved my pen to the ‘Yes’ box and in the bit below, where I had to elaborate, I wrote: ‘Hazelnuts—cause shortness of breath and lips to swell.’

And on the bit about current medication I made sure to remind this Lisa why I was here and boldly wrote my order.

Valium.

I put Roz down as my emergency contact, even though she had no idea I was here.

A woman, presumably Lisa, opened the door and gave me a patronising smile as she took my forms, then invited me to follow her.

On sight I didn’t like her.

I certainly couldn’t imagine myself relating to her, or her to me. She was a big woman, about sixty, with massive, pendulous breasts. Worse, she wore a really low-cut olive top, so you could see her crêpe chest and cleavage. Add to that a flowing A-line, snot-green skirt, green sandals. And she had accessorised with—in case we hadn’t noticed her colour choice for today—a huge jade necklace.

There were four seats for me to choose from. No doubt the one I chose would mean something, and I hesitated for a moment, before settling for the one in the middle.

‘Excuse all the furniture…’ She gave a pussycat smile. ‘I had a family in before you.’

Lucky them, then.

I put down my bag, checked my keys were there, zipped it up and sat back. There was a bowl of sweets on her desk, cola bottles, snakes, wine gums, all my favourites really, and I stared at them instead of her.

‘So…’ Lisa finally broke the silence. ‘What brought you here today?’

I so did not need this. Last night had been a one-off drunken mistake, I’d by now decided, and I’d learnt my lesson—I was never mixing alcohol with Valium again.

‘Okay,’ she said to the ensuing silence. ‘Why don’t you tell me about Alice?’ I could feel a really inappropriate smile start to wobble on my lips. I couldn’t believe I was sitting in a psychologist’s office being asked to discuss me in the third person. ‘Alice is English?’

‘She is,’ my twitching lips answered.

Well, we skirted around for a bit, I told her I had to leave promptly, that my flatmate was going to the UK and I had to take her to the airport.

‘Nicole’s English as well?’ Lisa checked.

‘She’s been here five years,’ I said. ‘She’d never leave.’

Lisa wrote a little note but I couldn’t make out what it was.

‘You’ll miss her?’

‘I guess,’ I admitted. Though lately we hadn’t been getting on too well. Not that I’d tell Lisa that, so instead I mentioned that Nicole’s cousin Hugh, a doctor, was arriving in a couple of days and staying till he found somewhere near the hospital to live.

‘You don’t look too pleased.’

‘I like my own company.’ I shrugged. ‘I was looking forward to a few weeks to myself.’

Actually, that had nothing to do with it.

Normally I’d be thrilled to have the good doctor to myself, but I’d found out from Nic that he was a redhead—need I say more?

I know that sounds anti-redhead, but I’m allowed to be, because I am one.

Think Ronald McDonald meets Shirley Temple.

I had the kind of hair that stopped old ladies in the street, made them pat it as they chattered away to my mother.

‘Beautiful hair. Of course, she’ll hate it later.’

I hated it already. By the time I was six it regularly reduced me to tears. Hour after hour was spent in front of my mother’s dressing-table mirror trying to brush out the curls. Night after uncomfortable night was spent sleeping with pins speared into my scalp in the hope of producing a straight fringe by morning. And as for the colour! I’d barely hit puberty before I bought my first hair dye and even now a very significant portion of my monthly pay cheque is spent on foils, serum, ceramic straighteners, regular blow-dries and, if I ever save up enough, I’m getting that Brazilian keratin treatment.

Though I digress, there is a point—my hair is now strawberry blonde and straight. For the first time in my life I’m actually pleased with my hair and I do not need a reminder of the au naturel version of myself walking around the flat.

Not that Lisa needed to hear that.

Honestly, it was the most boring, pointless hour of my life.

Yes, I suppose sometimes I did get a bit homesick.

Yes, I’d been here for nearly ten years now since my sister Bonny had got married and emigrated.

‘But you only initially came to Melbourne for a year?’

‘That’s right.’ I nodded. ‘I just loved it, though. I got a good job…’

‘Doing what?’

‘Working on the classifieds section at the newspaper. Well, it was a good job at the time.’

‘And you’re still there?’ She peered at the form I had filled in.

I felt myself pink up just a little bit. ‘I’m a team manager now and I do web updates.’ I gave a little shrug. ‘It’s not my ideal job, of course…’

‘What is your ideal job?’

‘I don’t know…’ another shrug ‘… something in music, I suppose. My exam results weren’t great. That was one of the reasons I came in the first place—to have a break and work out what I was going to do.’

We chatted some more, or rather she dragged information out of me. ‘And are the rest of your family here?’

‘Just Bonny. My mum and Eleanor, she’s the oldest, live back in the UK.’

‘And your father?’

I felt my face redden. I mean, I hadn’t meant to leave him out. ‘He’s in the UK too.’ I waited for her to scribble something down, but she didn’t. ‘They’re divorced. I speak to him and everything… it’s no big deal.’

‘When did they divorce?’

‘When I was fifteen.’

Well, it would seem that I had my Valium. She pounced on the fact my parents were divorced. Really, she worried away at it for the rest of the hour. How did I feel when they broke up, had there been rows? I couldn’t convince her that it hadn’t been that bad. I mean, you hear all these terrible tales, but the truth is, Mum let herself go after I came along, Dad met Lucy and left. We still saw him. Every Friday night we stayed over while Mum did a night shift, and then on Saturday lunchtime he took us to the pub for lunch, just as he had done when they were still married. Mum had been upset, of course—depressed, in hindsight—but it really wasn’t that much of a big deal at the time. I told Lisa that as she started jotting down a little family tree and making copious notes.

‘Look, I’m not here about that.’ And I supposed, if I wanted the prescription, I was going to have to tell her. ‘I had an anxiety attack.’ My cheeks were flaming as I cringed at the memory of Olivia’s leaving do last week. Everyone gathering around, offering me water, paramedics, being strapped to a stretcher and taken down in the lifts and out onto the street. ‘Really, I’m not even sure that it was an anxiety attack—the doctors at the hospital thought it might be an allergic reaction.’ She frowned. ‘I had a similar thing when I was seven and I ate hazelnuts.’ But still she just sat there. ‘The medicine they gave me at the hospital really helped, though.’

‘The Valium?’

‘Yes.’ I gave a little swallow. ‘I’m worried it might happen again, but if I had some Valium, just till I get the allergy tests done…’

‘You could just avoid hazelnuts!’ I swear her eyes crinkled. Honestly, I felt as if she was laughing at me, which she couldn’t be, of course.

But then she did.

She laughed.

I couldn’t believe it. She didn’t sit there and roar, but she gave a little laugh that made her shoulders go up. The type you do when you say something amusing, only this wasn’t funny.

I’d get her struck off.

If she didn’t give me my script.

‘Okay.’ She glanced at her watch and managed to contain herself enough for another little scribble on her pad. ‘If you can make an appointment again for about two weeks’ time. Now, don’t be surprised if you feel a bit unsettled over the next couple of days—we’ve touched on some sensitive areas.’

Which was news to me.

‘But what about…?’ I gave a nervous swallow as she stood. ‘The doctor said I should see a psychologist if I needed more Valium. He was only comfortable giving me ten.’

‘That’s very sensible.’

God, she wasn’t making this easy—I wasn’t asking her to buy them, just to write the bloody script.

I decided to go for direct. ‘Do you think you could write me up for some?’

‘I don’t prescribe medication.’

What the hell? My ears were ringing from her words as she droned on. I’d been through all of this, all of this, and she still refused to write me up for drugs—what did she suggest then? Was she some sort of alternative psychologist, was she going to suggest meditation? ‘I’m happy to write a note for your GP explaining that you are seeing me.’

‘But the doctor at the hospital said I should come and see you.’ I could hear my voice rising. I’d taken my last Valium yesterday and I had none left.