Полная версия

Полная версияThe Letters of Cicero, Volume 1

78

See end of Letter XXI. Cicero playfully supposes that Atticus only stayed in his villa in Epirus to offer sacrifices to the nymph in his gymnasium, and then hurried off to Sicyon, where people owed him money which he wanted to get. He goes to Antonius first to get his authority for putting pressure on Sicyon, and perhaps even some military force.

79

C. Calpurnius Piso (consul b.c. 67), brother of the consul of the year, had been governor of Gallia Narbonensis (b.c. 66-65), and had suppressed a rising of the Allobroges, the most troublesome tribe in the province, who were, in fact, again in rebellion.

80

M. Pupius Piso.

81

"By the expression of his face rather than the force of his expressions" (Tyrrell).

82

See p. 27, note 2.

83

Pompey.

84

Or, "inclose with my speech"; in both cases the dative orationi meæ is peculiar. No speech exists containing such a description, but we have only two of the previous year extant (pro Flacco and pro Archia Poeta). Cicero was probably sending it, whichever it was, to Atticus to be copied by his librarii, and published. Atticus had apparently some other works of Cicero's in hand, for which he had sent him some "queries."

85

Apparently the speech in the senate referred to in Letter XIV, p. 23, spoken on 1st January, b.c. 62. Metellus had prevented his contio the day before.

86

The letter giving this description is lost. I think frigebat is epistolary imperfect—"he is in the cold shade," not, "it fell flat."

87

πανήγυρις. Cicero uses the word (an honourable one in Greek) contemptuously of the rabble brought together at a market.

88

Pompey's general commendation of the decrees of the senate would include those regarding the Catiline conspirators, and he therefore claimed to have satisfied Cicero.

89

Meis omnibus litteris, the MS. reading. Prof. Tyrrell's emendation, orationibus meis, omnibus litteris, "in my speeches, every letter of them," seems to me even harsher than the MS., a gross exaggeration, and doubtful Latin. Meis litteris is well supported by literæ forenses et senatoriæ of de Off. 2, § 3, and though it is an unusual mode of referring to speeches, we must remember that they were now published and were "literature." The particular reference is to the speech pro Imperio Pompeii, in which, among other things, the whole credit of the reduction of Spartacus's gladiators is given to Pompey, whereas the brunt of the war had been borne by Crassus.

90

Fufius, though Cicero does not say so, must have vetoed the decree, but in the face of such a majority withdrew his veto. The practice seems to have been, in case of tribunician veto, to take the vote, which remained as an auctoritas senatus, but was not a senatus consultum unless the tribune was induced to withdraw.

91

Comperisse. See Letter XVII, note 1, p. 28.

92

See Letters XVI and XVIII, pp. 26, 32.

93

παντοίης ἀρέτης μιμνήσκεο (Hom. Il. xxii. 8)

94

The allotment of provinces had been put off (see last letter) till the affair of Clodius's trial was settled; consequently Quintus would not have much time for preparation, and would soon set out. He would cross to Dyrrachium, and proceed along the via Egnatia to Thessalonica. He might meet Atticus at Dyrrachium, or go out of his way to call on him at Buthrotum.

95

ὕστερον πρότερον Ὁμηρικῶς.

96

That is, the resolution of the senate, that the consuls should endeavour to get the bill passed.

97

Cicero deposed to having seen Clodius in Rome three hours after he swore that he was at Interamna (ninety miles off), thus spoiling his alibi.

98

The difficulty of this sentence is well known. The juries were now made up of three decuriæ—senators, equites, and tribuni ærarii. But the exact meaning of tribuni ærarii is not known, beyond the fact that they formed an ordo, coming immediately below the equites. Possibly they were old tribal officers who had the duty of distributing pay or collecting taxes (to which the translation supposes a punning reference), and as such were required to be of a census immediately below that of the equites. I do not profess to be satisfied, but I cannot think that Professor Tyrrell's proposal makes matters much easier—tribuni non tam ærarii, ut appellantur, quam ærati; for his translation of ærati as "bribed" is not better supported, and is a less natural deduction than "moneyed."

99

I.e., the Athenians. Xenocrates of Calchedon (b.c. 396-314), residing at Athens, is said to have been so trusted that his word was taken as a witness without an oath (Diog. Laert. iv. ii. 4).

100

Q. Cæcilius Numidicus, consul b.c. 109, commanded against Iugurtha. The event referred to in the text is said to have occurred on his trial de repetundis, after his return from a province which he had held as proprætor (Val. Max. ii. x. 1).

101

Hom. Il. xvi. 112:

ἕσπετε νῦν μοι, Μοῦσαι, Ὀλύμπια δώματ' ἔχουσαιὅππως δὴ πρῶτον πῦρ ἔμπεσε νηυσὶν Ἀχαίων.102

The reference is to Crassus. But the rest is very dark. The old commentators say that he is here called ex Nanneianis because he made a large sum of money by the property of one Nanneius, who was among those proscribed by Sulla. His calling Crassus his "panegyrist" is explained by Letter XIX, pp. 33-34.

103

C. Curio, the elder, defended Clodius. He had bought the villa of Marius (a native of Arpinum) at Baiæ.

104

Q. Marcius Rex married a sister of Clodius, and dying, left him no legacy.

105

L. Afranius.

106

Reading deterioris histrionis similis, "like an inferior actor."

107

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, married to Cato's sister. Consul b.c. 54. A strong aristocrat and vehement opponent of Cæsar.

108

Aufidius Lurco had apparently proposed his law on bribery between the time of the notice of the elections (indictio) and the elections themselves, which was against a provision of the leges Ælia et Fufia. What his breach of the law was in entering on his office originally we do not know: perhaps some neglect of auspices, or his personal deformity.

109

I.e. to Quintus Cicero, now proprætor in Asia, who apparently wished his brother-in-law to come to Asia in some official capacity.

110

Some epigrams or inscriptions under a portrait bust of Cicero in the gymnasium of Atticus's villa at Buthrotum. Atticus had a taste for such compositions. See Nepos, Att. 18; Pliny, N. H. 35, § 11.

111

Cicero had defended Archias, and Thyillus seems also to have been intimate with him: but he says Archias, after complimenting the Luculli by a poem, is now doing the same to the Cæcilii Metelli. The "Cæcilian drama" is a reference to the old dramatist, Cæcilius Statius (ob. b.c. 168).

112

Of Amaltheia, nurse of Zeus in Crete, there were plenty of legends. Atticus is making in his house something like what Cicero had made in his, and called his academia or gymnasium. That of Atticus was probably also a summer house or study, with garden, fountains, etc., and a shrine or statue of Amaltheia.

113

Cicero is evidently very anxious as to the misunderstanding between Quintus and his brother-in-law Atticus, caused, as he hints, or at any rate not allayed, by Pomponia. The letter is very carefully written, without the familiar tone and mixture of jest and earnest common to most of the letters to Atticus.

114

At the end of the via Egnatia, which started from Dyrrachium.

115

The election in question is that to be held in b.c. 60 for the consulship of b.c. 59. Cæsar and Bibulus were elected, and apparently were the only two candidates declared as yet. They were, of course, extremists, and Lucceius seems to reckon on getting in by forming a coalition with either one or the other, and so getting the support of one of the extreme parties, with the moderates, for himself. The bargain eventually made was between Lucceius and Cæsar, the former finding the money. But the Optimates found more, and carried Bibulus. Arrius is Q. Arrius the orator (see Index). C. Piso is the consul of b.c. 67.

116

Reading (mainly with Schutz) animus præsens et voluntas, tamen etiam atque etiam ipsa medicinam refugit. The verb refugit is very doubtful, but it gives nearly the sense required. Cicero is ready to be as brave and active as before, but the state will not do its part. It has, for instance, blundered in the matter of the law against judicial corruption. The senate offended the equites by proposing it, and yet did not carry the law. I think animus and voluntas must refer to Cicero, not the state, to which in his present humour he would not attribute them.

117

The temple of Iuventas was vowed by M. Livius after the battle of the Metaurus (b.c. 207), and dedicated in b.c. 191 by C. Licinius Lucullus, games being established on the anniversary of its dedication (Livy, xxi. 62; xxxvi. 36). It is suggested, therefore, that some of the Luculli usually presided at these games, but on this occasion refused, because of the injury done by C. Memmius, who was curule ædile.

118

By Agamemnon and Menelaus Cicero means Lucius and Marcus Lucullus; the former Memmius had, as tribune in b.c. 66-65, opposed in his demand for a triumph, the latter he has now injured in the person of his wife.

119

A man who was sui iuris was properly adopted before the commitia curiata, now represented by thirty lictors. What Herennius proposed was that it should take place by a regular lex, passed by the comitia tributa. The object apparently was to avoid the necessity of the presence of a pontifex and augur, which was required at the comitia curiata. The concurrent law by the consul would come before the comitia centuriata. The adopter was P. Fonteius, a very young man.

120

L. Afranius, the other consul.

121

M. Lollius Palicanus, "a mere mob orator" (Brutus, §223).

122

The toga picta of a triumphator, which Pompey, by special law, was authorized to wear at the games. Cicero uses the contemptuous diminutive, togula.

123

To be absent from the census without excuse rendered a man liable to penalties. Cicero will therefore put up notices in Atticus's various places of business or residence of his intention to appear in due course. To appear just at the end of the period was, it seems, in the case of a man of business, advisable, that he might be rated at the actual amount of his property, no more or less.

124

A special title given to the Ædui on their application for alliance. Cæsar, B. G. i. 33.

125

The migration of the Helvetii did not actually begin till b.c. 58. Cæsar tells us in the first book of his Commentaries how he stopped it.

126

Consul b.c. 69, superseded in Crete by Pompey b.c. 65. Triumphed b.c. 62.

127

Prætor b.c. 63, defended by Cicero in an extant oration.

128

Cn. Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus, consul in b.c. 72. Cicero puns on the name Lentulus from lens (pulse, φακή), and quotes a Greek proverb for things incongruous. See Athenæus, 160 (from the Necuia of Sopater):

Ἴθακος Ὀδυσσεὺς, τὸ ἐκὶ τῇ φακῇ μύρονπάρεστι· θάρσει, θυμέ.129

b.c. 133, the year before the agrarian law of Tiberius Gracchus. The law of Gracchus had not touched the public land in Campania (the old territory of Capua). The object of this clause (which appears repeatedly in those of b.c. 120 and 111, see Bruns, Fontes Iuris, p. 72) is to confine the allotment of ager publicus to such land as had become so subsequently, i.e., to land made "public" principally by the confiscations of Sulla.

130

That is, he proposed to hypothecate the vectigalia from the new provinces formed by Pompey in the East for five years.

131

The consulship. The bribery at Afranius's election is asserted in Letter XXI.

132

The day of the execution of the Catilinarian conspirators.

133

Epicharmus, twice quoted by Polybius, xviii. 40; xxxi. 21. νᾶφε καὶ μέμνας' ἀπιστεῖν, ἄρθρα ταῦτα τῶν φρενῶν.

134

Pedarii were probably those senators who had not held curule office. They were not different from the other senators in point of legal rights, but as ex-magistrates were asked for their sententia first, they seldom had time to do anything but signify by word their assent to one or other motion, or to cross over to the person whom they intended to support.

135

P. Servilius Vatia Isauricus, son of the conqueror of the Isaurians. As he had not yet been a prætor, he would be called on after the consulares and prætorii. He then moved a new clause to the decree, and carried it.

136

The decree apparently prevented the recovery of debts from a libera civitas in the Roman courts. Atticus would therefore have to trust to the regard of the Sicyonians for their credit.

137

A son must be hard up for something to say for himself if he is always harping on his father's reputation; and so must I, if I have nothing but my consulship. That seems the only point in the quotation. I do not feel that there is any reference to praise of his father in Cicero's own poem. There are two versions of the proverb:

τίς πατέρ' αἰνήσει εἰ μὴ κακοδαίμονες υἱοίand

τίς πατέρ' αἰνήσει εἰ μὴ εὐδαίμονες υἱοί.138

Contained in Letter XXII, pp. 46-47.

139

Reading tibi for mihi, as Prof. Tyrrell suggests.

140

Σπάρτην ἔλαχες κείνην κοσμεῖ. "Sparta is your lot, do it credit," a line of Euripides which had become proverbial.

141

οἱ μὲν παρ' οὐδέν εἰσι, τοῖς δ' οὐδεν μέλει. Rhinton, a dramatist, circa b.c. 320-280 (of Tarentum or Syracuse).

142

See pp. 52, 56, 65.

143

See p. 57.

144

The lex Cincia (b.c. 204) forbade the taking of presents for acting as advocate in law courts.

145

Nep. Att. c. 18.

146

Atticus seems to have seen a copy belonging to some one else at Corfu. Cicero explains that he had kept back Atticus's copy for revision.

147

Cicero evidently intends Atticus to act as a publisher. His librarii will make copies. See p. 32, note 1.

148

The passage in brackets is believed by some, not on very good grounds, to be spurious. Otho is L. Roscius Otho, the author of the law as to the seats in the theatre of the equites. The "proscribed" are those proscribed by Sulla, their sons being forbidden to hold office, a disability which Cicero maintained for fear of civil disturbances. See in Pis. §§ 4-5.

149

Pulchellus, i.e., P. Clodius Pulcher, the diminutive of contempt.

150

Where he had been as quæstor. Hera is said to be another name for Hybla. Some read heri, "only yesterday."

151

Clodius is shewing off his modesty. It was usual for persons returning from a province to send messengers in front, and to travel deliberately, that their friends might pay them the compliment of going out to meet them. Entering the city after nightfall was another method of avoiding a public reception. See Suet. Aug. 53.

152

See p. 37, note 3.

153

Clodia, wife of the consul Metellus. See p. 22, note.

154

We don't know who this is; probably a cavaliere servente of Clodia's.

155

I.e., in the business of her brother Clodius's attempt to get the tribuneship.

156

Though Cæsar has been mentioned before in regard to his candidature for the consulship, and in connexion with the Clodius case, this is the first reference to him as a statesman. He is on the eve of his return from Spain, and already is giving indication of his coalition with Pompey. His military success in Spain first clearly demonstrated his importance.

157

During the meeting of the senate at the time of the Catilinarian conspiracy (2 Phil. § 16).

158

The consul Cæcilius Metellus was imprisoned by the tribune Flavius for resisting his land law (Dio, xxxvii. 50).

159

M. Favonius, an extreme Optimate. Ille Catonis æmulus (Suet. Aug. 13). He had a bitter tongue, but a faithful heart (Plut. Pomp. 60, 73; Vell. ii 73). He did not get the prætorship (which he was now seeking) till b.c. 49. He was executed after Philippi (Dio. 47, 49).

160

P. Scipio Nasica Metellus Pius, the future father-in-law of Pompey, who got the prætorship, was indicted for ambitus by Favonius.

161

Ἀπολλόνιος Μόλων of Alabanda taught rhetoric at Rhodes. Cicero had himself attended his lectures. He puns on the name Molon and molæ, "mill at which slaves worked."

162

See pp. 57, 60.

163

Reading discessionibus, "divisions in the senate," with Manutius and Tyrrell, not dissentionibus; and deinde ne, but not st for si.

164

His study, which he playfully calls by this name, in imitation of that of Atticus. See p. 30.

165

See Letter XV, p. 25.

166

His translation of the Prognostics of Aratus.

167

Gaius Octavius, father of Augustus, governor of Macedonia.

168

The roll being unwound as he read and piled on the ground. Dicæarchus of Messene, a contemporary of Aristotle, wrote on "Constitutions" among other things. Procilius seems also to have written on polities.

169

Herodes, a teacher at Athens, afterwards tutor to young Cicero. He seems to have written on Cicero's consulship.

170

These remarks refer to something in Atticus's letter.

171

Gaius Antonius, about to be prosecuted for maiestas on his return from Macedonia.

172

P. Nigidius Figulus, a tribune (which dates the letter after the 10th of December). The tribunes had no right of summons (vocatio), they must personally enforce their commands.

173

"The Conqueror," i.e., Pompey. Aulus's son is L. Afranius.

174

I.e., his military get-up.

175

Cyrus was Cicero's architect; his argument or theory he calls Cyropædeia, after Xenophon's book.

176

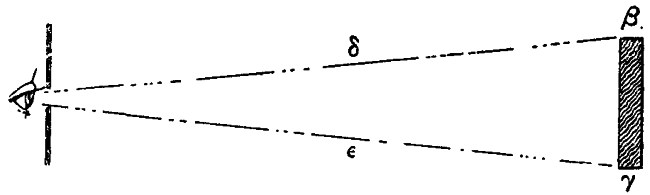

He supposes himself to be making a mathematical figure in optics:

177

The theory of sight held by Democritus, denounced as unphilosophical by Plutarch (Timoleon, Introd.).

178

Apparently a villa in the Solonius ager, near Lanuvium.

179

The Cornelius Balbus of Gades, whose citizenship Cicero defended b.c. 56 (consul b.c. 40). He was Cæsar's close friend and agent.

180

Cicero was apparently not behind the scenes. The coalition with Pompey certainly, and with Crassus probably, had been already made and the terms agreed upon soon after the elections. If Cicero afterwards discovered this it must have shewn him how little he could trust Pompey's show of friendship and Cæsar's candour. Cæsar desired Cicero's private friendship and public acquiescence, but was prepared to do without them.

181

From Cicero's Latin poem on his consulship.

182

εἶς οἰωνός ἄριστος ἀμύνεσθαι περὶ πάτρης (Hom. Il. xii. 243).

183

A country festival and general holiday. It was a feriæ conceptivæ, and therefore the exact day varied. But it was about the end of the year or beginning of the new year (in Pis. § 4; Aul. Gell. x. 24; Macrob. Sat. i. 4; ad Att. vii. 5; vii. 7, § 2).

184

Of the persons mentioned, L. Ælius Tubero is elsewhere praised as a man of learning (pro Lig. § 10); A. Allienus (prætor b.c. 49) was a friend and correspondent; M. Gratidius is mentioned in pro Flacco, § 49, as acting in a judicial capacity, and was perhaps a cousin of Cicero's.

185

The class of Romans who have practically become provincials.

186

Rome and its society and interests.

187

Father of Augustus, governor of Macedonia, b.c. 60-59. But he seems to refer to his prætorship (b.c. 61) at Rome; at any rate, as well as to his conduct in Macedonia.

188

Reading primum; others primus, "his head lictor."

189

That is, if it ends in his death, for Meliodorus of Skepsis was sent by Mithridates to Tigranes to urge him to go to war with Rome, but privately advised him not to do so, and, in consequence, was put to death by Mithridates (Plut. Luc. 22). The word Scepsii (Σκηψίου) was introduced by Gronovius for the unintelligible word Syrpie found in the MSS., which so often blunder in Greek names.

190

Clodius, alluding to his intrusion into the mysteries.

191

Atticus has asked Cicero for a Latin treatise on geography—probably as a publisher, Cicero being the prince of book-makers—and to that end has sent him the Greek geography of Serapio.