Полная версия

Полная версияItalian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car

The “Villas” of Naples are often mere maisons bourgeoises of modern date. Many of them might well be in Brixton so far as their architectural charms go.

Over in the Posilippo quarter, a delightful situation indeed, are innumerable flat-topped, whitewashed villas, so-called, entirely unlovely, all things considered. One of these, the Villa Rendel, was once inhabited by Garibaldi, as a tablet on its wall announces.

Garibaldi and the part that he and his red shirt played are not yet forgotten. Apropos of this there is a famous lawsuit still in the Italian courts, wherein the Garibaldian Colonel Cornacci, in accord with Ricciotti Garibaldi, son of the general, makes the following claim against the Italian government:

I. All the “tresor” (gold and silver) of the house of Bourbon.

II. Eleven millions of ducats taken from the Garibaldian government at Naples.

III. The Bourbon museum now incorporated with the National Museum.

IV. The Palace of Caserta and its park.

V. The Palace Farnese at Rome.

VI. The Palace and Villa Farnese at Caprarola at Naples.

VII. Two Villas at Naples, Capodimonte and La Favorita.

This is the balance sheet discrepancy resulting from the war of 1860 which the Garibaldian heirs claim is theirs by rights. It’s a mere bagatelle of course! One wonders why the Italian government don’t settle it at once and be done with it!

Naples is the birth-place of Polichinelle, as Paris is of Pierrot, two figures of fancy which will never die out in literature or art, a tender expression of sentiment quite worthy of being kept alive.

The Neapolitan, en fête, is quite the equal in gayety and irresponsibility of the inhabitant of Seville or Montmartre. The processionings of any big Italian town are a thing which, once seen, will always be remembered. At Naples they seem a bit more gorgeous and spontaneous in their gayety than elsewhere, with rugs and banners floating in the air from every balcony, and flowers falling from every hand. It is every man’s carnival, the celebration at Naples.

Leading out to the west, back of Posilippo, is the Strada di Piedigrotta, which is continued as the Grotto Nuovo di Posilipo, and through which runs a tramway, all kinds of animal-drawn wheeled traffic, and automobiles with open exhausts. All this comports little with the fact that the ancient tunnelled road along here was one of the marvels of engineering in the time of Augustus and that it led to Virgil’s tomb. This supposed tomb of Virgil is questioned by archæologists, but that doesn’t much matter for the rest of us. We know that Virgil himself has said that it was here that he composed the “Georgics” and the “Æneid,” and it might well have been his last resting-place too.

“Addio, mia bella Napoli! Addio!”

CHAPTER XII

THE BEAUTIFUL BAY OF NAPLES

“SEE Naples and die” is all very well for a sentiment, but when we first saw it, many years ago, it was under a grim, grey sky, and its shore front was washed by a milky-green fury of a sea.

Fortunately it is not always thus; indeed it is seldom so. On that occasion Vesuvius was invisible, and Posilippo in dim relief. What a contrast to things as they usually are! Still, Naples and its Bay are no phenomenal wonders. Suppress the point of view, the focus of Virgil, of Horace, of Tiberius and of Nero, and the view of “Alger la Blanche,” or of Marseilles and its headlands, is quite as beautiful. And the Bay of Naples is not so beautifully blue either; the Bai de la Ciotat in Maritime Province is often the same colour, and has a nearby range of jutting, jagged, foam-lashed promontories that are all that Capri is – all but the grotto.

The Bay of Naples has its moods, and there are times when its blueness is more apparent than at others; in short there are times when it looks more beautiful than at others, and then one is apt to think its charms superlative.

The praises of the ravishing beauty of the Bay of Naples have been sung by the poets and told in prose ever since the art of writing travel impressions has been known, but though the half may not have been told it were futile to reiterate what one may see for himself if he will only come and look. “A piece of heaven fallen to earth,” Sannazar has said, and certainly no one can hope to describe it with more glowing praise.

For the artist the whole Neapolitan coastline, and background as well, is a riot of rainbow colouring such as can hardly be found elsewhere except in the Orient. It is not only that the Bay of Naples is blue, but the greys and drabs of the ash and cinders of Vesuvius seem to accentuate all the brilliant reds and yellows and greens of the foliage and housetops, not forgetting the shipping of the little ports and the costuming of land-lubbers and sailor-men, and of course the women. The Italian women, young or old, are possessed of about the loveliest colouring of any of the fair women of the twentieth century portrait gallery.

The environs of Naples have two plagues which, when they rise in their wrath, can scarcely be avoided. One is the sirocco, that dry, stiff wind which blows along the Mediterranean coast in summer, coming from the African shore and the desert beyond, and the much worse, or at least more dreaded, aria cattiva, which is supposed to blow the sulphurous gases and cinders of Vesuvius down the population’s throats, and does to a certain extent.

Out beyond Posilippo, which itself is properly enough bound up with the life of Naples, lies Pouzzoles. The excursion is usually made in half a day by carriage, and automobilists have been known to do it in half an hour. The former method is preferable, though the automobilist is free from the rapacious Neapolitan cab driver and that’s a good deal in favour of the new locomotion. If only automobilists as a class wouldn’t be in such a hurry!

Pouzzoles has no splendid palaces but it has the remains of a former temple of Augustus in the shape of twelve magnificent Corinthian columns, built into the Cathedral of Saint Procule, and some remains of another shrine dedicated to Serapis. There are also the ruins of Cicero’s villa at Baies, a little further on. Mont Gauro, where the “rough Falernian” wine, whose praises were sung by Walter de Mapes, comes from, shelters the little village on one side and Mont Nuovo on the other, this last a mountain or hillock of perhaps a hundred and fifty metres in height, which grew up in a night as a result of a sixteenth century earthquake.

The Lake of Averno is nearby, a tiny body of water whose name and fame are celebrated afar, but which as a lake, properly considered, hardly ranks in size with the average mill-pond. With a depth of some thirty odd metres and a circumference of three kilometres its charms were sufficient to attract Hannibal thither to sacrifice to Pluto, and Virgil there laid the “Descent into Purgatory.” Agrippa, with an indomitable energy and the help of twenty thousand slaves, made it into a port great enough to shelter the Roman fleet. At Baies there is a magnificent feudal work in the form of a fortress-château of Pedro of Toledo (1538).

At the tiny port of Torregaveta, just beyond, one takes ship for Procida and Ischia, two islands often neglected in making the round of Naples Bay.

Procida, off shore three or four kilometres, and with a length of about the same, has a population of fifteen thousand, most of whom rent boats to visitors. Competition here being fierce, prices are reasonable – anything you like to pay, provided you can clinch the bargain beforehand.

Ischia is twice the size of Procida, twice the distance from the mainland and has twice the population of the latter. One might say, too, that it is twice as interesting. It is a vast pyramid of rock dominated by a château-fort dating from 1450. It looks almost unreal in its impressiveness, and since it is of volcanic growth the island may some day disappear as suddenly as it came. Such is the fear of most of the population.

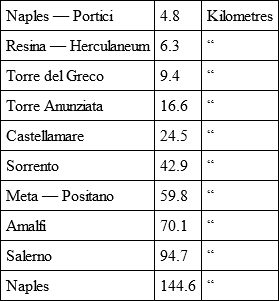

A quick round south from Naples can be made by following the itinerary below. It can be done in a day or a week, but in the former case one must be content with a cinematographic reminiscence.

Some one has said that Vesuvius was a vicious boil on the neck of Naples. There is not much sentiment in the expression and little delicacy, but there is much truth in it. Still, if it were not for Vesuvius much of the charm and character of the Bay of Naples and its cadre would be gone for ever.

All around the base of the great cone are a flock of little half-baked, lava-burned villages, as sad as an Esquimaux settlement in the great lone land. This is the way they strike one as places to live in, though the artist folk find them picturesque enough, it is true, and a poet of the Dante type would probably get as much inspiration here as did Alighieri from the Inferno.

It has been remarked before now that Italy is a birdless land. The Renaissance poets sang differently, but judging from the country immediately neighbouring upon Vesuvius, and Calabria to the southward, one is inclined to join forces with the first mentioned authority. Not even a carrion crow could make a living in some parts of southern Italy.

So desolate and lone is this sparsely populated region towards the south that it is about the only part of Italy where one may hope to encounter the brigand of romance and fiction.

The thing is not unheard of to-day, but what brigands are left are presumably kidnappers for political purposes who wreak their vengeance on some official. The stranger tourist goes free. He is only robbed by the hotel keepers and their employees who think more of buona mano than anything else. A recent account (1907), in an Italian journal, tells of the adventures of the master of ceremonies at Victor Emmanuel’s court who was captured by bandits and imprisoned in a cave in that terra incognita back of Vesuvius away from the coast.

Newspaper accounts are often at variance with the facts, but these made thrilling reading. One account said that the kidnappers tore out the Marquis’s teeth, one by one, in order to force him to write a letter asking for ransom. As he still refused, lights were held to the soles of his naked feet.

The Marquis was lured from Naples to the neighbourhood of a grotto in the direction of Vesuvius, where he was seized by the brigand’s confederates.

“I was seized unexpectedly from behind,” said the Marquis in his version, “and after a sharp struggle with my unseen assailants was carried down into the grotto with Herculanean force and tightly bound.

“Then, liberating my right arm, the brigands fetched a lamp and writing materials, covering their faces with masks. Threatening me with instant death, the chief forced me to write a letter to my friends demanding that money be sent me forthwith. At the same time he took from me all my valuables and then disappeared, leaving me a prisoner with a guard before the entrance of my cave.”

The adventure ended harmlessly enough, and whether it was all a dream or not of course nobody but the Marquis knows. At any rate it has quite a mediæval ring to it.

Pompeii is remarkable, but it is disappointing. All that is of real interest has been removed to the Naples museum. Without its Forum and its magnificent temples and Vesuvius as a toile de fond Pompeii would be a dreary place indeed to any but an archæologist. It is a waste of time to view any restored historic monument where modern house painters have refurbished the old half-obliterated frescoes. The famous Cave Canem, too, the only mosaic that remains intact, has been twice removed from its original emplacement. Yes, Pompeii is a disappointment! It is too much of a show-place!

The most notable observation to be made with regard to the admirable architectural details of Pompeii is that they are all on a diminutive scale. The colonnade of the Forum, for instance, could never be carried out on the magnificent scale of the Roman Forum, and indeed, when modern architects have attempted to reproduce the façade of a tiny pagan temple, as in the Église de la Madeleine, or the Palais Bourbon at Paris, they have failed miserably.

The rival claims of the Hotel Suisse and the Hotel Diomede at Pompeii (to say nothing of that of the Albergo del Sol opposite the entrance to the Amphitheatre) make it difficult for the stranger to decide upon which to bestow his patronage.

The artists go to the Albergo del Sol, which is rough and uncomfortable enough from many points of view, and the tourists of convention go to one of the other two, where they are “exploited” a bit but get more attention. At any one of these hotels one can hire a horse to climb up the cone of Vesuvius, if one thinks he would like such rude sport, and prices are anything he will pay, about five or six francs, though it costs another two francs for a guide and another two francs for the ragamuffin who follows after and holds the horses while you explore the crater. If the latter was blacking boots in New York, even for a padrone, at five cents a shine, he would make more money and be counted out of the robber class. As it is he is a rank impostor and needless – provided you have the courage to refuse his services.

The contrast between Herculaneum and Pompeii is notable. Herculaneum was buried under thirty metres of liquid lava, but Pompeii was buried only roof-high under cinders. Herculaneum will some day be uncovered to the extent of Pompeii, and then it is probable the world will have new marvels at which to wonder.

The rewards from the excavation of Herculaneum may well be commensurate with the toil. It was an infinitely more important place than Pompeii, which was only a little country town without libraries or particularly wealthy inhabitants. Herculaneum, on the other hand, was the summer resort of wealthy Romans, who spent their lives in adorning their beautiful villas with the choicest work of Greek art. Pliny said that they had a mania for collecting Greek silver and other works of art, and at prices that would even make the wealthiest art connoisseurs of to-day pause for thought. Agrippina, among others, had her villa here. Herculaneum remains intact and undespoiled, as it was more than eighteen centuries ago.

From Pompeii to Sorrento via Castellamare is twenty-five kilometres.

Sorrento is, in summer, a bathing place for such of the Neapolitan high-life population as are not able to get far away from home. One properly enough attaches no importance whatever to the gay life of the boulevards, the cafés and the restaurants of Naples. It is the same thing as at Rome, Paris and London over again with all its silly flaneries, but here at Sorrento, or across the peninsula at Amalfi, life is less feverish and one may stroll about or indeed live free and tranquil from care in hotels, less luxurious no doubt than those of the Quai Parthenope, but offering a sufficient degree of comfort to make them agreeable to the most exacting.

The real winter birds of passage only alight here for a period of three or four weeks in January or February. After that it is delightful, except for the short period when it is given up to the crowd of tourists which invariably comes at Easter.

Sorrento is the great centre for all the charming region bordering upon the southern shore of the Bay of Naples. It is at once the city and the country. Its hotels are delightfully disposed amid flowering gardens or on a terrace overlooking the escarpments of the rock-bound coast. Six or seven francs a day, or eight or ten, according to the class of establishment one patronizes, and one finds the best of simple fare and comfort. Eight days or a fortnight one may roam about the neighbourhood at Sorrento, from Sant Agatha on a nearby height to Sejano Castellamare, Positano, Amalfi and finally Capri. There is hardly such a range of charming little towns and townlets to be found elsewhere in all the world.

Except for its restricted little business quarter the houses and villas of Sorrento are disposed on the best of “garden city” plans. Again a plague on a beauty spot must be admitted: mosquitoes will all but devour you here between mid-August and the end of October. The only safe-guard is to paint yourself with iodine, but the cure is as bad as the complaint.

The traveller in Italy learns of course to beware of coral, of white, pink and milky coloured coral. We had been afraid to even look at such ever since we had seen it being made by the ton in Belgium – and good looking “coral” it was.

Once the artist bought a string of the real thing at Tabarka in Tunisia, and once a friend who was with us on the Riviera di Ponente bought a necklet of what was called coral, at an outrageous price, of a wily boatman. It all went up in smoke (accompanied by a vile smell) ultimately, though fortunately it was not on the owner’s neck at the time. It was an injudicious mixture of gun-cotton, nitroglycerine or what not. It wasn’t coral; that was evident.

Now, when we walk out at Sorrento, no Graziella, her shoulders scintillating with ropes of coral, beguiles us into buying any of her family heirlooms. To sum up: the coral which is sold to tourists is often false; that which is fished up before your eyes from the sea is always so. Beware of the coral of Sorrento or Capri.

The trip to Capri is of course included in every one’s itinerary in these parts, and for that reason it is not omitted here, though indeed the famous grotto over which the sentimentally inclined so love to rave has little more charm than the same thing represented on the stage. This at any rate is one man’s opinion. It is most conveniently reached by boat from Sorrento.

The famous retreat of Augustus and the scene of the debauches of Tiberius will ever have an attraction for the globe-trotter, even though its romance is mostly fictitious. One may gather any opinions he chooses, and, provided he gathers them on the spot and makes them up out of his own imaginings, he will be content with Capri’s grotto; only he mustn’t take the guide-books too seriously.

The Blue Grotto’s goddess is Amphitrite, and if any one catches a glimpse of her traditional scanty draperies swishing around a corner, let him not be misguided into following her into her retreat. If he does the sea is guaranteed to rise and close the orifice so that he may not get out again as soon as he might wish.

In that case one must wait till the wind, which has veered suddenly from east to west, comes about again and blows from the south. Without bringing Amphitrite into the matter at all it sometimes happens that visitors entering the grotto for a pleasant half hour may be obliged to stay there two, three or even five days. The boatmen-guides, providing for such emergencies, carry with them a certain quantity of biscotti with which to sustain their victims. As for fresh water it trickles through into the grotto in several places in a sufficient quantity to allay any apprehensions as to dying of thirst. One might well blame the Capri guides for not calling the visitor’s attention to these things. But if one is reproached he simply answers: “Ma che! eccelenza, if we should call attention to this thing, half the would-be visitors would balk at the first step, and that would be bad for our business.”

Alexandre Dumas tells of how on a visit to Capri in 1835 the fisherman was pointed out to him who had ten years earlier re-discovered the Blue Grotto of Augustus’ time, whilst searching for mussels among the rocks. He went at once to the authorities on the island and told them of his discovery and asked for the privilege of exploiting visitors. This discoverer of a new underground world was able by means of graft, or other means, to put the thing through and lived in ease ever after, through his ability to levy a toll on other guides to whom he farmed out his privilege.

Quite the best of Capri is above ground, the isle itself, set like a gem in the waters of the Mediterranean. The very natural symphonic colouring of the rocks and hillsides and rooftops of its houses, and indeed the costuming of its very people, make it very beautiful.

For Amalfi, Salerno and Pæstum the automobilist must retrace his way from Sorrento to Castellamare, when, in thirty kilometres, he may gain Amalfi, and, in another twenty-five, Salerno. Pæstum and its temples, to many the chief things of interest in Italy, the land of noble monuments, lie forty kilometres away from Salerno. The automobilist, to add this to his excursion out from Naples, is debarred from making the round in a day, even if he would. It is worth doing however; that goes without saying, though the attempt is not made here of purveying guide-book or historical information. If you don’t know anything about Pæstum, or care anything about it, then leave it out and get back to Naples as quickly as you can, and so on out of the country at the same rate of speed.

CHAPTER XIII

ACROSS UMBRIA TO THE ADRIATIC

THE mountain district of Umbria, a country of clear outlines against pale blue skies, is one of the most charming in the peninsula though not the most grandly scenic.

The highway from Rome to Ancona, across Umbria, follows the itinerary of one of the most ancient of Roman roads, the Via Valeria. The railway, too, follows almost in the same track, though each leaves the Imperial City, itself, by the great trunk line via Salaria and the Valley of the Tiber.

Terni is the great junction from which radiate various other lines of communication to all parts of the kingdom. Terni is, practically, the geographical centre of Italy. It is a bustling manufacturing town and, supposedly, the Interamna where Tacitus was born.

From Terni one reaches Naples, via Avezzano in 257 kilometres; Rome, via Civita Castellana in 94 kilometres; Florence via Perugia and Arezzo in 256 kilometres and Ancona, on the shores of the Adriatic, via Foligno in 209 kilometres. All of these roads run the gamut from high to low levels and, though in no sense to be classed as mountain roads, are sufficiently trying to even a modern automobile to be classed as difficult.

The Cascades of Terni used to be one of the stock sights of tourists, a generation ago, but, truth to tell, they are not remarkable natural beauties, and, indeed, are too apparently artificial to be admired. Moreover one is too much “exploited” in the neighbourhood to enjoy his visit. It costs half a lira to enter by this gate, and to leave by that road; to cross this bridge, or descend into that cavern; and troops of children beg soldi of you at every turn. The thing is not worth doing.

Spoleto, twenty-six kilometres away, is somewhat more interesting. It is famous for the fine relics, which still exist, of its more magnificent days, when, 242 B. C., it was named Spoletium.

The towers of Spoleto, like those of San Gimignano and Volterra, are its chief glory; civic, secular and churchly towers, all blending into one hazy mass of grim, militant power. The Franciscan convent, on the uppermost height, seems to guard all the towers below, as a shepherd guards his flock, or a mother hen her chickens.

In 1499 the equivocal, enigmatic Lucrezia Borgia came to inhabit the castle of Spoleto. The fair but unholy Lucrezia was a wandering, restless being who liked apparently to be continually on the move.

Here, in the fortress of Spoleto, Lucrezia Borgia, coming straight from the Vatican, held for a brief year the seals of the state in her frail hands, her father at the time being governor.

The aspect of this grim fortress-château, grim but livable, as one knows from the historical accounts, is to-day, so far as outlines are concerned, just as it was five centuries ago. It is grandiose, severe and majestic, and is dominant in all the landscape round about, not even its mountain background dwarfing its proportions. The military defence was that portion lying lowest down in the valley, while the residence of the governor was in the upper portion. One reads the history of three distinct epochs in its architecture, the Gothic of the fifteenth century, that of the sixteenth, and the later interpolated Renaissance decorations.

Through Foligno and Assisi runs the road to Perugia. Assisi is a much visited shrine, but Foligno is remembered by most of those who have travelled that way only as a grimy railway junction.