Полная версия:

Wilfred Thesiger: The Life of the Great Explorer

They reached the outskirts of Addis Ababa on 10 December, where they were met by the retiring Consul, Lord Herbert Hervey, with an escort of Indian sowars, troopers, in full dress uniform, an Abyssinian Ras and various ministers of state. Later, in an undated memoir, Kathleen described her first impressions of the British Legation, her home for the next nine years:

The Legation lies on a hillside outside the town with vast and beautiful views of the surrounding mountains. I was told that the Legation compound is the same size as St James’s Park. In 1909 the large and imposing stone building in which we later lived in such comfort did not exist and we arrived to a settlement of thatched huts or ‘tukuls’. Each room was a separate round mud hut joined to the next one by a ‘mud’ passage and the whole built round a grassed courtyard with a covered way down the middle. [This accommodation had been planned by Wilfred Gilbert’s predecessor, Captain (later Sir) John Harrington, and was being constructed when the writer Herbert Vivian arrived at Addis Ababa in 1901.]

The servants’ quarters – kitchens etc., stood at the back. The sowars’ quarters and the stables stood higher up on the hillside and the native ‘village’ where the Abyssinian servants lived lay in a hollow beneath them. ‘Mud hut’ is not really at all descriptive of those charming round thatched rooms; always cool in summer and warm in winter. They were wonderfully spacious and most comfortable to live in, although at that time our furniture was very primitive. The [ceiling] was not boarded over, but rose with thatch to a point in the centre and the supporting laths of wood were inter-wound with many gay colours. The effect was enchanting…I shall never forget our first meal that evening. Roast wild duck I most particularly remember! Our head servants were Indians and we had an excellent Goanese cook…12

In the first draft of her memoir Kathleen recalled that the furniture ‘was mostly made from packing-cases but we had some very handsome “pieces” and a few comfortable beds’.13 Wilfred Gilbert wrote to his mother: ‘Kathleen is making cushion covers and tablecloths…the effect of a circular room is rather good only one does miss the corners.’14 He eulogised the Legation’s compound, with its

masses of glorious big rose bushes smothered in blossom [and] a bed of scarlet geraniums…rather tangled and wild, but very pretty. Tall Eucalyptus trees make an inner boundary and our compound is a square about a quarter of a mile each way. A big field serves for grazing and hay making and will allow a little steeple chase course all round. There is a good tennis court [and] a regular village of little stone circular houses for the servants…All round are highish hills broken and covered with scrub and to the East a big plain with mountains all round…the evening lights are very beautiful…15

During the week before Christmas 1909, Captain Thesiger had his first formal audience with Menelik’s grandson, Lij Yasu (or ‘Child Jesus’), who was attended by the corrupt Regent, Ras Tasamma. Thousands of Abyssinian soldiers riding horses or mules escorted Thesiger’s parents to the Emperor’s palace, the gibbi, which crowned the largest hill at Addis Ababa. ‘At that first meeting,’ Thesiger wrote, ‘my father can have had no idea of the troubles this boy would bring on his country.’16 The previous year Menelik had appointed Lij Yasu, then aged thirteen, as his heir. By 1911, when Lij Yasu seized power, the government of Abyssinia had begun to crumble. Five years later, Captain Thesiger would report to the Foreign Office that ‘Lij Yasu…has succeeded in destroying every semblance of central government and is dragging down the prestige of individual ministers so that there is no authority to whom the Legation can appeal.’17

The Thesigers, meanwhile, each recorded impressions of that first audience: ‘a big affair and a wonderful sight’,18 wrote Wilfred Gilbert, while Kathleen found it ‘magnificent beyond my wildest dreams’.19 Wilfred Gilbert continued:

As at Harar the big men wore their crowns with fringes of lions’ mane standing up all round and the skins of leopards and lions over their gold embroidered silk and velvet mantles, an escort of Galla horsemen in the same dresses, each with two long spears rode on either side on fiery little horses and added immensely to all the movement…We circled the walls of the palace to the far gate and here there was a great rush to get into the inner court on the part of the Abyssinians and various gorgeously dressed chiefs told off for the purpose, but right and left with long bamboos to keep out the unauthorised, they did not spare the rod. One chief in full dress hit over the head missed his footing and rolled down the steep entrance to my mule’s feet. I expected he would hit back, but it seemed part of the game, get in if you could, but accept blows if you can’t. Another stick smashed to splinters on the head of a less gorgeous official…

Inside a large courtyard lined with soldiers a brass band play[ed] a European tune for all they were worth, others with long straight trumpets, like those played by angels in [stained] glass windows, negroes with long flutes all added to the din…We passed into another court by an archway…and came to the central one where the walls were lined by chiefs only. We rode into the centre and dismounted and formed our little procession. I went first with the interpreter, then Kathleen, Lord Herbert [Hervey], Dr Wakeman, and behind them the escort on foot…

I went on alone up the steps to the foot of the throne in front of which Lij Yasu sat with all his big officials and after being introduced…I read my little speech and then handed it over to the interpreter to be translated and when he had finished I handed over the letter to Menelik to Lij Yasu who then read his speech which was interpreted by the court dragoman. I then asked leave to present Kathleen and went back to bring her up with the others…It was a very impressive ceremony. The hall is an enormous building very dimly lighted with pillars of wood on either side, the floor…strewn with green rushes and a long carpet down the centre.20

Later that day, after the presentation ceremony, the Thesigers met Lij Yasu again at Ras Tasamma’s residence. Wilfred Gilbert praised Lij Yasu: ‘a nice boy of clear cut Semitic features and very shy…when something amused us he caught my eye and laughed and then suddenly checked himself’. He added cautiously: ‘Everyone was very friendly but at present I am only on the surface of things.’21 Kathleen wrote that for the occasion ‘Wilfred was wearing full diplomatic uniform and I my smartest London frock [her ‘going away’ dress worn after her wedding] and a large befeathered hat. To the European eye we surely would have presented an amusing spectacle more especially as the “diplomatic mule” [ridden by Wilfred Gilbert] was also in full dress with gaily embroidered coloured velvet hanging, and tinkling brass and silver ornaments.’

Kathleen’s candid account of the feast that followed might have been borrowed from James Bruce of Kinnaird’s Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790), a work whose descriptions of alleged Abyssinian customs, such as eating raw meat cut from live oxen, had been dismissed as nonsense by critics following Dr Johnson, who doubted that Bruce had ever been there:

Course after course, one more uneatable than another and served by very questionably clean slave women. This feast lasted quite interminably, or so it seemed to me. But at last it ended…and the curtains surrounding the daïs [where we sat] were suddenly drawn back and a vast Hall was revealed below us crowded with thousands of soldiery. An incredible number of them packed like sardines and all wearing the usual white Abyssinian ‘Shamma’. They sat on benches stretching into the far distance, and between these benches there was just room for two men to walk in single file. These men carried a pole on their shoulders which stretched from one to the other, and from this pole was suspended half the carcase of a freshly killed ox. Each man, as it passed him, pulled out his knife and skilfully cut for himself as large a piece of bleeding meat as possible and this he proceeded to eat pushing it into his mouth with his left hand and with his right cutting off a chunk which I think he gulped down whole – and so on until all was finished. Eventually the soldiery filed out somehow and I shall always remember our exit, because, for some reason we went out by the door at the end of the great Hall and to do so we had to pick our way through the bloody remains of the Feast.22

In The Real Abyssinia (1927), Colonel C.F. Rey described a ‘raw meat banquet’ on this scale, marking the Feast of Maskal, when ‘no fewer than 15,000 soldiers and 2000 or 3000 palace retainers were fed in four relays in the great hall’.23 The way of life Kathleen Thesiger had left behind in England must have appeared at that moment incredibly remote. Yet it would be events such as the Regent’s feast that gave her eldest son Wilfred his craving for ‘barbaric splendour’ and ‘a distaste for the drab uniformity of the modern world’.24

England and home were brought suddenly into sharp focus by the death of King Edward VII in May 1910, news of which affected the Thesigers almost like a family bereavement. Captain Thesiger wrote to his mother on 14 May: ‘What a terrible blow the King’s death has been…We had heard nothing of his short illness to prepare us. Even now it seems impossible to believe and realize it.’25 Edward VII died four weeks before the younger Wilfred Thesiger was born. The King’s death signalled the waning of an era, which the First World War would finally end. In the microcosm of Addis Ababa’s British Legation, ‘everything [was]…put off, polo, races, gymkhana and lunches’. To Wilfred Gilbert and Kathleen it seemed ‘as tho’ everything had suddenly come to a stop’.26

FOUR ‘One Handsome Rajah’

In the heart of the British Legation’s dusty compound at Addis Ababa, Wilfred Patrick Thesiger was born by the light of oil lamps at 8 p.m. on Friday, 3 June 1910, in a thatched mud hut that served as his parents’ bedroom. The following day his father wrote to Lady Chelmsford, the baby’s grandmother: ‘Everything passed off very well and both are doing splendidly. He weighs 8½lb and stands 1ft 8in [corrected in another letter to 1ft 10in] in his bare feet and his lungs are excellent…He is a splendid little boy and the Abyssinians have already christened him the “tininish Minister” which means the “very small Minister”. We are going to call him Wilfred Patrick but he is always spoken of as Billy. He has a fair amount of hair, is less red than might have been expected and has long fingers.’1

On 12 July Thesiger was christened at Addis Ababa by Pastor Karl Cederquist, a Swedish Lutheran missionary. Count Alexander Hoyos and Frank Champain were named as godfathers; his godmothers were Mrs John Curre and Mrs Miles Backhouse, the wives of two British officials. Captain Thesiger reported proudly: ‘The man Billy [whom he called ‘a jolly little beggar’] grows very fast and puts on half a pound every week with great regularity. I think he is quite a nice looking baby. He has a decided nose and rather a straight upper lip, his eyes seem big for a baby and are wide apart.’2 Frank Champain had accepted his role as the baby’s godfather with reluctance. He would write to Wilfred in 1927: ‘Sorry to have been such a rotten Godfather. I told your Dad I was no good…I can’t be of much use but if I can I am yours to command.’3

Thesiger’s good looks, inherited from his father, were strengthened by his mother’s determined jaw and her direct (some thought intimidating) gaze. As a baby he was active, alert and observant. His adoring parents took photographs of him at frequent intervals from the age of one month until he was nine. They preserved these photographs in an album, the first of four similar albums they compiled, one for each of their sons. Some of the earliest photographs show Billy cradled in his mother’s arms or perched unsteadily on his nurse Susannah’s shoulder, grasping her tightly by her hair. Susannah, a dark-skinned Indian girl, stayed with the Thesigers for three years, working for some of the time alongside an English nurse who proved so incapable and neurotic that Wilfred Gilbert felt obliged to dismiss her. To the devoted, endlessly patient Susannah, little Billy could do no wrong. ‘When my mother remonstrated with her,’ Thesiger wrote, ‘she would answer, “He one handsome Rajah – why for he no do what he want?”’4 Thesiger may have heard his mother tell this story, mimicking Susannah’s broken English.

Though he walked at an unusually early age, Thesiger admitted that he had been slow learning to speak. He said his mother told him that his first words were ‘“Go yay” which meant “Go away” and showed an independent spirit’.5 One day the Thesigers found Billy in Susannah’s hut, lying on the earth floor surrounded by the servants, who bent over him performing a mysterious rite. Susannah reassured the astonished couple: ‘We were just tying for all time to our countries.’6

The child’s birthplace, a circular Abyssinian tukul of mud and wattle with a conical thatched roof, like an East African banda or a South African rondavel, could scarcely have been a more appropriate introduction to the life he was destined to lead. Thesiger realised this, and used to talk about being born in a ‘mud hut’, which implied that the circumstances of his birth were more primitive than they had been in reality. He also liked to stress any extraordinary adventures during childhood which helped to explain his longing for a life of ‘savagery and colour’7 In his early fifties Thesiger confessed that he had probably exaggerated his preferences and dislikes – his resentment, for instance, of cars, aeroplanes and twentieth-century technology foisted on remote societies he called ‘traditional peoples’. He wrote in The Marsh Arabs:

Like many Englishmen of my generation and upbringing I had an instinctive sympathy with the traditional life of others. My childhood was spent in Abyssinia, which at that time was without cars or roads…I loathed cars, aeroplanes, wireless and television, in fact most of our civilisation’s manifestations in the past fifty years, and was always happy, in Iraq or elsewhere, to share a smoke-filled hovel with a shepherd, his family and beasts. In such a household, everything was strange and different, their self-reliance put me at ease, and I was fascinated by the feeling of continuity with the past. I envied them a contentment rare in the world today and a mastery of skills, however simple, that I myself could never hope to attain.8

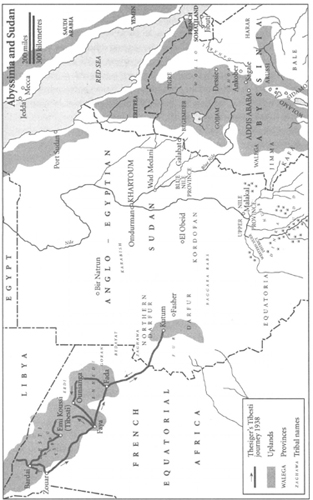

Thesiger did not experience this sense of easy harmony among remote tribes at Addis Ababa, nor indeed for many years after he first left Abyssinia. Throughout his childhood and his teens, even as a young man in his early twenties, he lived in a European setting, with European values imposed by his family. He had felt instinctively superior by virtue of his background, education and race. Until the 1930s, he admitted, he was ‘an Englishman in Africa, travelling very much as my father would have travelled’.9 He fed and slept apart from the Africans who accompanied him. In 1934 in Abyssinia he read Henri de Monfreid’s book Secrets de la Mer Rouge, and afterwards sailed aboard a dhow from Tajura to Jibuti. Sitting on deck, sharing the crew’s evening meal of rice and fish, Thesiger realised that this was how he wanted to live the rest of his life. During the next fifteen years he accustomed himself to living as his tribal companions lived, in the Sudan, the French Sahara and Arabia. Meanwhile, reflecting on his influential childhood in Abyssinia, he said: ‘When I returned to England [with my family in 1919] I had already witnessed sights such as few people had ever seen.’10

Aged only eight months, early in 1911 Thesiger was taken by his parents on home leave. Carried in a ‘swaying litter between two mules’,11 the baby travelled three hundred miles from Addis Ababa to the railhead at Dire Dawa, and from there by train and steamer to England. A few months later this long journey was repeated in reverse, following the same route Thesiger’s parents had taken in November 1909. ‘The water for his baby food on these treks had to be boiled and then strained through gamgee tissue; his nurse hunted out the tent for camel ticks before he went to bed at night.’ Once, when Thesiger’s nurse had carried him a short distance from camp, they found themselves face to face with a party of half-naked warriors. ‘But she need not have worried, the warriors were just intrigued by a white baby; they had never seen such a sight before.’12

In 1911, to avoid the hot weather, Thesiger and his mother, escorted as far as Jibuti by an official from the Legation, travelled to England ahead of his father, who arrived there on 15 June with members of an Abyssinian mission representing the Emperor at the coronation of King George V. The second of Wilfred Gilbert and Kathleen’s sons, Brian Peirson Thesiger, was born at Beachley Rectory in Gloucestershire on 4 October 1911. Wilfred Gilbert had bought the house, with its large overgrown garden overlooking the Severn estuary, to provide his expanding family with a home of their own in England. Billy and Brian became inseparable. Sixteen months older, Billy dominated his younger brother, who seemed content to follow his lead. Those who knew the two elder Thesigers affirmed that this continued for the whole of Brian’s life. Whereas Wilfred Thesiger and his youngest brothers, Dermot Vigors (born in London on 24 March 1914) and Roderic Miles Doughty (born in Addis Ababa on 8 November 1916), had inherited their parents’ looks, Brian bore little obvious resemblance either to the Thesigers or to the Vigors. From his mother’s side no doubt came his reddish fair hair and his freckled, oval face – colouring and features which set him apart from Wilfred, Dermot and Roderic. In his late twenties Brian’s face showed more bone structure, but even then he bore little resemblance to his brothers. Lord Herbert Hervey’s successor as Consul at Addis Ababa, Major Charles H.M. Doughty-Wylie, nicknamed Brian ‘carrot top’ because of his red hair.13 Roderic Thesiger was named after Charles Doughty (who had changed his name to Doughty-Wylie before he married, in 1907, a rich and ‘capable’ widow, Lily Oimara (‘Judith’) Wylie).

Thesiger’s childhood recollections from the age of three or four were clear, lasting and vivid. He remembered his father’s folding camp table with Blackwood’s Magazine, a tobacco tin and a bottle of Rose’s lime juice on it. He remembered, aged three, seeing his father shoot an oryx, the mortally wounded antelope’s headlong rush, and ‘the dust coming up as it crashed’.14 How many animals he saw his father kill for sport we don’t know. The only others he recorded apart from the oryx were two Indian blackbuck, ‘each with a good head’,15 and a tiger his father shot and wounded in the Jaipur forests in 1918 but failed to recover. Such sights as these had thrilled Thesiger as a boy; they fired his passion for hunting African big game, most of which he did in Abyssinia and the Sudan between 1930 and 1939. He continued to hunt after the Second World War in Kurdistan, the marshes of southern Iraq and in Kenya. By the time he arrived in northern Kenya in 1960, however, his passion for hunting was almost exhausted, and he only shot an occasional antelope or zebra for meat.

In 1969 Thesiger told the writer Timothy Green how as children he and Brian sat up at dusk in the Legation garden, waiting to shoot with their airguns a porcupine that had been eating the bulbs of gladioli. ‘Before long Brian, who was only three, pleaded “I think I hear a hyena, I’m frightened, let’s go in.” “Nonsense,” said Wilfred, “you stay here with me.” Finally, long after dark, when the porcupine had not put in an appearance, Wilfred announced, “It’s getting cold. We’ll go in now.”’16 Thesiger’s conversation shows how, aged less than four and a half, he was already taking charge in his own small world. He went on doing so all his life. A born gang leader, Thesiger dominated his brothers, just as, as a traveller, he would dominate his followers.

He was aware of this tendency, and in later years he strove to play it down. In My Kenya Days, he stated: ‘Looking back over my life I have never wanted a master and servant relationship with my retainers.’17 A key to this is his instinctive use of the term ‘retainers’: literally ‘dependants’, or ‘followers of some person of rank or position’. Throughout his life he surrounded himself with often much younger men, or boys, who served him and gave him the companionship he desired. Many of them, initially, owed Thesiger their liberty, or favours in exchange for financial assistance he gave them or their families. These favours affected their relationship with him, in which the distinction between servant and comrade was frequently blurred.

As a child Thesiger had ruled over his younger brothers, even using them as punchbags after he learnt to box. The ‘fagging’ system at Eton encouraged his thuggish behaviour, which was tolerated only by friends who realised that he had a gentler side, which he kept hidden for fear of diluting his macho image. It was characteristic of him, from his mid-twenties onward, that he would choose ‘retainers’ younger than himself, over whom he exerted an authority reinforced by the difference between their ages, as well as by his dominating personality and his position or status – for example, as an Assistant District Commissioner in the Sudan, and in Syria an army major ranked as second-in-command of the Druze Legion. In contrast, Thesiger’s relationships with his older followers were seldom as close or as meaningful. The same applied to his young companions in Arabia and Iraq after they became middle-aged and, in due course, elderly men. Thesiger reflected: ‘I don’t know why it was. They were just different. We had travelled together in the desert and shared the hardships and danger of that life. When I saw them again, thirty years later, they lived in houses with radios and instead of riding camels they drove about in cars. The youngsters I remembered had grey beards. They seemed pleased to see me again, and I was pleased to see them; but something had gone…the feeling of intimacy, and a sense of the hardships that once bound us together.’18

At the Legation, Thesiger’s parents encouraged the children to play with pet animals, including a tame antelope, two dogs and a ‘toto’ monkey his mother named Moses. Kathleen wrote: ‘Altho’ we kept [Moses] chained to his box at times, we very often let him go and then he would rush away and climb to the nearest tree top, only to jump unexpectedly from a high branch on to my shoulder with unerring aim. Every official in the Legation loved my Moses and he was so small that they could carry him about in their pockets. He was accorded the freedom of the drawing room [in the new Legation] and I must confess that I still have many books in torn bindings [which] tell the tale.’19

Thesiger remembered Moses and the tiny antelope wistfully, with an amused affection. He commented in My Kenya Days: ‘My father kept no dogs in the Legation,’20 but this was a lapse of memory. Later he remembered: ‘Our first dog in Addis Ababa was called Jock. The next dog had to be got rid of because Hugh Dodds [one of Wilfred Gilbert’s Consuls] thought it was dangerous. This was about 1916…As a child, I was afraid of nothing but spiders…When we were at The Milebrook, the first dog I owned was a golden cocker spaniel, and it died of distemper. I had only had the dog for about a year.’21

In The Life of My Choice Thesiger pictured his childhood at Addis Ababa against a background of Abyssinia in turmoil. This was the chaotic legacy of the Emperor Menelik’s paralysing illness and his heir Lij Yasu’s blood-lust, incompetence and apostasy of Islam. The turbulent decade from 1910 to 1919 gave the early years of Thesiger’s life story romance and power, and enhanced the significance of his childhood as a crucial influence upon ‘everything that followed’.22 As a small boy he was no doubt aware of events he described seventy years later in The Life of My Choice, however remote and incomprehensible they must have appeared at the time. In reality his life at Addis Ababa had little to do with the Legation’s surroundings – except for its landscapes, including the hills (Entoto, Wochercher and Fantali) and the plain where Billy and Brian rode their ponies and went on camping trips every year with their parents. On these memorable outings Mary Buckle, a children’s nurse from Abingdon in Oxfordshire, accompanied the family. Mary, known to everyone as ‘Minna’, had been engaged in 1911 to look after Brian. Thesiger wrote in 1987: ‘She was eighteen and had never been out of England, yet she unhesitatingly set off for a remote and savage country in Africa. She gave us unfailing devotion and became an essential part of our family.’23 Just as he idealised his father and mother, Thesiger idealised Minna, whom he admired as brave, selfless and indispensable. He wrote affectionately in The Life of My Choice: ‘Now, after more than seventy years, she is still my cherished friend and confidante, the one person left with shared memories of those far-off days.’24 This statement was literally true. Thesiger, a confirmed bachelor, respected strong-willed, practical women, mother figures whose common sense and devotion tempered their undisputed authority. Thesiger’s occasional travelling companion and close friend Lady Egremont later remembered visiting Minna with him at Witney in Oxfordshire. She watched as he smoothed his hair and straightened his tie, ‘like a twelve-year-old schoolboy on his best behaviour’,25 as they waited for Minna to open her front door.