Полная версия:

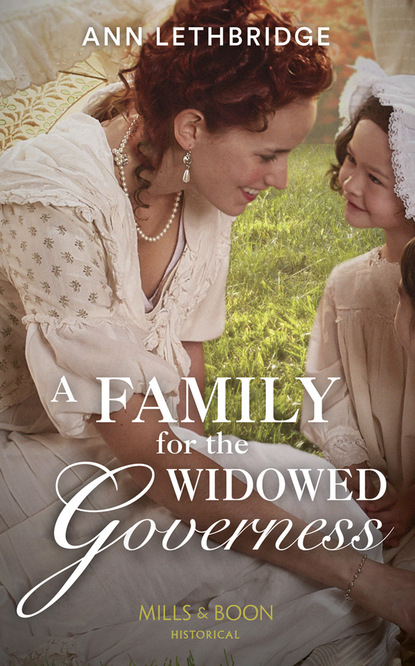

A Family For The Widowed Governess

If indeed she had any coal.

There had been a good pile of logs at the back door, though. Hopefully, his lad would have the sense to split them when he ran out of work in the stables. Jack went to his desk, looked at the pile of paperwork and then went to the window. It was nearly two in the afternoon. She should be here at any moment. Unless she intended to be fashionably late.

But no. He smiled at the sight of the trap advancing up his drive at a steady clip. He went outside to greet her.

A groom ran out from the stables to take her horse and held it steady while he helped her down. She was dressed in the same dun-brown coat she had worn the day she brought his daughters home. And as on that occasion, her hair was neatly pinned beneath a plain cap and covered by a serviceable bonnet with the sprig of daisies on the brim a startling little nod to femininity.

‘Good afternoon, Lord Compton,’ she said coolly.

‘Good afternoon, Lady Marguerite.’

She gave him a tight little smile. ‘Where might I find my charges?’

‘In the nursery. Come. I will show you the way.’

He had spent his own childhood in this nursery with his own nanny. She’d been a little livelier than Nanny James was now. Certainly spryer. But there was no one else he would trust as much as he trusted her to care for his children.

Sounds of excited talking and giggling grew louder as they walked along the corridor. He made his step extra heavy, the sound echoing off the walls. The sounds ceased. He threw open the door and the three children were lined up in a row opposite, just as he had requested the previous evening. As was her wont, Nanny James was sitting beside the hearth, rocking back and forth and smiling at the little row of children. He smiled at them. His children were a credit to him.

‘Good afternoon, daughters,’ he said.

‘Good afternoon, Papa,’ the older two chorused, showing off their best curtsies. Netty removed her thumb from her mouth with a little pop and wobbled when she bent her knees. He really should try to have Nanny break her of the habit of thumb-sucking. He just didn’t have the heart. She was still barely more than a baby. And besides, as Nanny always said when he discussed the matter with her, how many adults did he know who walked around sucking their thumbs?

‘Ladies, this is Lady Marguerite, whom you know already. She has kindly agreed to give you drawing lessons. You will behave and do exactly as she says.’

‘Yes, Papa,’ they said in unison.

He handed Lady Marguerite the paper he had prepared that morning. ‘This is a list of rules with regard to the children’s activities. Please ensure they are followed.’

Lady Marguerite took the list with raised eyebrows. ‘I will let you know if I think they are suitable.’

He gritted his teeth. ‘They are my rules.’

‘I see.’ She glanced around the nursery. ‘We cannot work in here, I am afraid. The girls need tables, easels and drawing implements.’

He’d thought of that. ‘Let me show you the schoolroom. I am sure you will find it meets your needs.’

He led her to the very end of the hallway and opened the door. ‘Will this do?’

It was a large airy space that he and his wife had prepared for the large brood they had expected. They had incorporated it into this wing of the house with a good deal of joyful anticipation. Now it only made him feel sad.

Lady Marguerite nodded. ‘This will do very well, my lord.’

‘The cupboard contains supplies I obtained on the instructions of the last two governesses. I recall they included things like pens and ink and charcoal.’

She crossed to the cupboard and scanned its contents. He could not help but admire the way she strode across the room with a purposeful step. She was ladylike, but also confident as his wife had never been. Which was why he still did not understand why on earth she would have gone out when night was drawing in on foot and alone. A lie. To himself. He knew why. She had gone alone and without talking to him because she knew he would not approve.

‘This looks like a very good start,’ Lady Marguerite said and turned to face him.

‘Excellent. Let me know if anything else is required.’

She glanced around. ‘If we could have this table moved closer to the window, it would be better.’

‘I’ll send a man up to do it.’

She nodded and looked down at his note. She ran her eye down the list and frowned. ‘This is very restrictive, my lord.’

‘As you have seen already, the girls are not easy to manage. I believe these rules will ensure their safety.’

She took a little breath and he had the feeling she intended to argue with him about his instructions. Instead, she gave a little shake of her head. ‘And my fee?’

He handed over four guineas. ‘For this week. We will discuss the future on Friday.’

She slipped the money into her reticule. ‘About the groom you sent to my house—’

‘No need to thank me. I am simply ensuring you arrive on time to give your lessons.’

‘But—’

‘No buts. I do not want the smell of horses in my daughters’ schoolroom.’

She glared at him and muttered something under her breath. It sounded a bit like ‘Men. Impossible.’

He pretended not to hear. ‘Shall we fetch Elizabeth and Janey?’

She pressed her lips in a straight line and for one long moment he thought she was going to refuse to teach them. Then her shoulders drooped a fraction and she nodded.

Damnation. He should be pleased, not feeling like a bully. He was right about needing to establish proper rules and regulations. He was the girls’ papa. He could not risk anything happening to them. This was the best way to keep them safe.

Chapter Three

Marguerite showed the girls how to draw basic shapes—squares, circles, triangles and ovals—and set them to practising on slates. There was no sense in using up valuable paper for this exercise. Lizzie was reluctant, but eventually complied.

While the girls worked she stood behind them and, with one eye on what they were doing, she reread His Lordship’s list of rules.

The children were to remain in the schoolroom at all times. They were to be walked from the nursery and back again. Walked. No running allowed. They were to have a snack sent up after the first hour of lessons. They were not to go outside or downstairs. She was also to make sure they minded their manners and, if they were rude, she was to report them to Nanny or himself.

She frowned. Were their lives so completely regimented? The man seemed to want to control every aspect of what they did or did not do. A shiver ran down her spine. She had not grown up under such strict controls, but she had experienced it with her husband. It had been awful. Was Lord Compton like Neville? If so, could she actually be complicit in something she did not like or believe in?

‘Is this right, my lady?’ Janey asked.

She had drawn a lovely circle. One of the hardest things to master. The line wavered a bit here and there, but for a first try it was very good.

‘That is exactly what is needed,’ Marguerite said.

Janey put down her chalk and shook her hand. ‘That was hard.’

‘It is not easy,’ Marguerite admitted. ‘But it is worth the effort. Lizzie, how are you doing?’

The child sat back. She had copied all of the demonstrated shapes across her slate in a rather slapdash manner. The circle did not join up. The triangles lines overlapped. The square looked more like a diamond.

Marguerite smiled. ‘A very good first attempt.’ She drew a circle next to the one Lizzie had drawn. ‘See if you can get it looking a bit more even. The lines are supposed to touch.’

‘This is silly,’ Lizzie said, folding her hands across her chest. ‘I want to draw a picture. Not shapes.’

‘You cannot draw anything unless you know how to draw these shapes and several others I will show you,’ Marguerite said. ‘Everything is made up of shapes.’

Lizzie frowned. ‘I don’t understand. I want to draw a horse. It is horse shaped.’

Marguerite smiled. ‘Let us see, shall we?’ She moved to an empty space on the blackboard and started to draw. She showed them how circles and ovals and rectangles worked together to create the basic shape of a horse. ‘This is only the start,’ she said, turning to face them. ‘But this is why you need to know these shapes.’

Janey clapped her hands. ‘It looks just like a horse.’

Lizzie frowned. ‘That looks nothing like a real horse.’

‘But it will eventually,’ Marguerite said. She softened the lines, drew the mane and tail. ‘The better you get at controlling shapes, the easier it will become.’

Lizzie looked unconvinced, but rubbed her slate clean and started again.

A knock at the door. Their snack had arrived. Apples and cheese and milk, and tea for her. Well, at least the girls were properly fed. The two girls tore into the apples and gobbled up the cheese.

Marguerite laughed. ‘Slow down, ladies. Where are your manners?’

The girls stopped and stared at her. They continued to eat, but with much more decorum. Yet Marguerite had the feeling they were holding themselves back. As if they were starving. How could that be? Was it possible that they were deprived of food as some sort of punishment?

Once they had finished and cleaned up they went back to drawing on their slates.

* * *

By the end of the second hour, Marguerite had them connecting shapes.

‘Very soon, you will be ready to start putting your drawings on paper,’ she said as they cleared up the slates and chalks to put them away. ‘If you want to practise these shapes by yourself, you may.’

‘Oh, we are not allowed in here without a teacher,’ Lizzie announced. ‘And Papa is still looking for a governess for us.’

And when he found one, his need for her would be at an end. All governesses taught drawing along with the other necessary lessons a girl needed to prepare her for life. Indeed, drawing was the least important skill. Needlework, writing and reading were far more valuable.

‘Who is teaching you lessons at the moment?’

‘Nanny reads to us, when her eyes aren’t too tired,’ Janey said.

Marguerite frowned. This was not the way to bring up such spirited intelligent girls.

They walked back to the nursery. At the door, Lizzie turned and looked at her. ‘Are you coming back tomorrow.’

‘Not tomorrow, but the day after.’

Elizabeth gave her a narrow-eyed stare, as if she did not believe her.

Janey gave a little skip. ‘Goody. I like drawing.’ Lizzie ushered her into the nursery and then turned back. ‘You don’t have to come again if you don’t want to. I am teaching Janey to read.’ She went inside and shut the door.

What on earth did Lizzie mean? Since it had been a busy afternoon, with them learning lots of new things, Marguerite decided to ask her about it another time. She returned to the schoolroom for her outer raiment.

* * *

All afternoon, Jack had wanted to go up to the schoolroom to see how the girls were faring with their drawing teacher. He had personally overseen the snack to be taken up to them. What if the girls were misbehaving? What if Lady Marguerite was not following the rules? He had forced himself not to go and check. Until Lady Marguerite proved that she could not cope, he would leave her to it.

At precisely five minutes after four he went up to the schoolroom. The girls were not there and Lady Marguerite had her coat on and was putting on her bonnet.

‘They are back with Nanny,’ she said with a cool smile.

He frowned. ‘Oh, I see. How did they get on? Did they behave themselves?’

She nodded. ‘They did.’

That was a relief. He had threatened them with a fate worse than death if they did not behave like perfect little ladies with their new teacher. The odd thing was, the girls had never met Aunt Ermintrude. He had no idea why they had decided she was their worst nightmare. Perhaps it was his fault. He had threatened a visit from her often enough.

He stepped aside to allow Lady Marguerite to pass. ‘I asked one of the lads to bring the trap around,’ he said. ‘It is waiting at the front door. I will see you here on Friday.’

She hesitated. Devil take it, was she not telling him the truth when she said the girls had behaved themselves? He hadn’t seen any of the telltale signs that would indicate she was lying.

Lady Marguerite drew in a breath. ‘Yes. I will be here on Friday at two in the afternoon and not a minute later.’

He winced. She must be referring to his rules about timeliness. Well, he simply wanted to make things clear, that was all. It was better if everyone knew where they stood.

‘Allow me to escort you out.’

She shook her head. ‘No need. I know my way.’

And with that she whisked by him and down the stairs.

He was damned if he was going to chase after her, no matter how much he might want to.

* * *

Later that evening, Marguerite waited anxiously in the designated spot, hoping to discover the identity of this man who was causing her such distress. Unfortunately, the alley running beside the Green Man led to a row of labourers’ cottages behind it and it was hard to see anything at all since there was no moon this evening. This was not a good place to meet a man who offered nothing but threats.

Her heart thumped loudly in her chest. Her breathing sounded loud in her ears. She wanted to run.

The man who had sat in the pew behind her at Petra’s wedding in St George’s Church had been well-spoken and she had taken him for a gentleman. Now, she was beginning to doubt her judgement.

The sound of male laughter wafted from the inn as a door opened and spilled light into the alley. It closed, leaving the narrow lane seeming darker than ever. She swallowed.

The tap of footsteps on cobbles approached.

She held her breath.

‘You have the money?’ a cultured voice asked.

She could see only a silhouette in the gloom. ‘I do.’ She sounded a great deal calmer than she felt. A little spurt of pride gave her courage. She would not be intimidated or bullied by this man.

‘Hand it over.’

She held out a knitted purse containing the guineas Lord Compton had given her and the few other coins she had scraped together to make up the sum he demanded. ‘You have the sketch?’

The man plucked the purse from her hand. ‘Not until I have payment in full.’

Disappointed, but not surprised, she grimaced. ‘I could go to the authorities, you know.’

His chuckle sounded menacing. ‘And tell them what? That you have denigrated your future King and now do not want to pay a man you do not know for your disloyalty to remain unpublished? Even if they listen, your sketch will become public.’ His voice softened. ‘Pay me and it need never come to light.’

Embarrassment scoured her very soul at the recollection of what she had drawn.

‘Twenty-five pounds and you will be free of me for ever,’ he promised, his tone wheedling.

‘But I have just given you—’

‘A show of good faith, my dear. Next time you will bring me what I requested or bear the consequences.’

She shivered at the sneer in his voice and a strange sense of familiarity. Had she met this man before? Or was she simply recalling his voice from that first meeting?

‘How can I trust that you won’t ask for more then, too?’ She knew she sounded desperate.

‘I give you my word.’

As if she could trust the word of one such as he, even if he did sound like a gentleman. ‘No true gentleman would do something like this.’

His hand shot out and gripped her wrist. ‘Do not insult me or it will be the worse for you. One last payment of twenty-five pounds and the sketch is yours. Think of your family.’

She swallowed. ‘It will take more time to raise that amount. This was supposed to be part of it.’

‘You still have two weeks,’ he said.

It was a great deal of money to find in two weeks, even with the money from Lord Compton and the sale of what little jewellery she had left.

‘I can’t do it that soon,’ she said.

‘Two weeks or see it in every print shop in London.’

He sounded desperate. He needed the money as much as she needed this to be over and done.

She took a deep breath. ‘It is not possible. Three weeks.’ Surely she would have the payment from her publisher by then.

‘All right. Three. Not a day more. I will contact you to arrange our next meeting. Do not fail me.’ He turned and marched off.

Her knees felt weak. She put a hand to her heart. She felt as if she had won a major battle, even as she knew she had lost the war. She just wished she could be sure he had taken her seriously about it being her final payment. Because if he demanded more money next time, she would not pay another penny. And then she would have to face the world’s condemnation. She blanched, her courage failing.

No! She must stand her ground, no matter the consequences. Except those consequences were not only hers to bear. No, next time he would return the sketch. She had to believe him.

Despite the trouble her knees had supporting her weight, she made it to the end of the alley and out into the lane. The walk to Westram Cottage seemed impossibly far.

‘Lady Marguerite? Is that indeed you?’

She spun around, hand to heart. ‘Lord Compton?’

He had clearly just emerged from the Green Man. What a surprise to see him in Westram since he lived closer to Ightham.

‘What are you doing out here at this time of night?’ His voice contained suspicion.

‘I have been visiting a friend and am on my way home.’

‘Alone?’

Now he sounded shocked. Men. They always judged one, whether they had the right or not.

‘This is Westram,’ she said coolly. ‘Not the streets of London.’

‘Allow me to escort you to your front door, my lady.’ He bowed and held out his arm.

She would be an idiot to trust any man. He had come out of the inn. Men in their cups were inclined to be difficult. Neville had been at his most malicious when bosky.

‘I would not trouble you, my lord. It is only a few steps.’

‘It is no trouble at all.’

He was clearly going to insist. He did not sound drunk. He wasn’t swaying or slurring his words. Giving in to him might be better than refusing and arousing more curiosity.

Meekly, she took his arm, but she was ready to run if he showed any signs of aggression.

They walked together in silence. For such a big man, he stepped lightly and matched his stride to hers. The lane became dark as they moved away from the torchlight on the walls of the inn. She glanced around nervously.

‘Is everything all right?’ he asked.

She found herself listening carefully to his voice. It was nothing like the blackmailer’s light reedy tenor. Lord Compton’s voice was a pleasant rumbling bass.

‘Everything is fine, thank you,’ she said. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘Your hand trembled when you laid it upon my sleeve.’

Her throat became dry. Was her fear so obvious?

‘You startled me, looming out of the dark that way.’

‘I must beg your pardon, then.’ He walked a few more steps. ‘At this risk of sounding like too anxious a parent, may I ask you how you found my daughters? Were they truly co-operative?’

Why would he ask yet again? Was he trying to find some fault with his girls? Some transgression that required punishment? They had been so very timid in his presence.

‘They did very well at their lessons.’

‘And they did not plague you at all?’

She frowned. ‘Not at all.’

‘Good. They must like you.’

‘They need more than drawing lessons if they are to be properly educated. They scarcely know how to write their names.’

Another long silence. ‘I must seek another governess, I suppose.’ He sounded unwilling.

An idea popped into her head. A way to get the girls out from under his repressive rule. ‘Why not send them to school? There are several excellent academies in and around London where they can make friends with other girls of their age.’

As a child she had always wanted to go away to school after hearing Red’s stories of fun and companionship. It had fallen to her to care for Petra, Jonathan and Papa after Mama died and she had been needed at home. Her drawing and painting had been the one activity that allowed her a bit of freedom from responsibility.

‘No.’ He spoke with such vehemence she drew away from him.

‘It was merely a suggestion.’

‘I went away to school. I know the sort of high jinks that occur out of the eye of the schoolmasters.’ He thrust his elbow towards her and she set her jaw and once more took his arm. She could not risk alienating him. Not when she needed his money.

‘I am sure you know what is best for your children,’ she said as calmly as she could manage. ‘I did wonder, though...’

‘Yes?’

‘Well, perhaps they might like to go outdoors once in a while. To draw from nature. We could set easels up outside at the edge of the lawn and—’

‘They are better off in the schoolroom. They can see all the nature they need from the windows.’

She bit her lip. The man was impossible. ‘Children need fresh air. They need to run and climb and experience the world. I am not surprised they ran away if you do not give them a bit of freedom.’

He stiffened. ‘I will thank you to leave the decisions regarding my children’s welfare to me.’

She bit back a sharp retort. It really was none of her business how he decided to raise his children.

They reached her gate. The porch lantern she had left burning lit their path to the front door.

She put her key in the lock.

He shook his head. ‘What is your family thinking, leaving you to manage alone?’

How was this his business? Did he think to control her life, too? ‘My lord, I am a grown woman. I manage perfectly well.’ Or she would, if it were not for the man threatening to ruin her life.

The light from the lantern softened his features, making him look younger, and handsome, rather than forbidding. Her insides gave a little flutter of feminine appreciation. She froze. This was not a reaction she either expected or wanted. The meeting with the blackmailer must be playing on her nerves.

‘No woman alone is entirely safe, Lady Marguerite. As a magistrate, I have reason to know this. Walking out alone at night is in itself a recipe for disaster. And, you know, I have a vested interest in your safety. My daughters would not like to lose their teacher.’

With a start she recalled hearing that his wife had been murdered while out one evening alone. And he was not wrong. Only moments ago, in that dark alley she had been terrified for her life. ‘Then I shall be more careful in future.’

He bowed. ‘Goodnight, Lady Marguerite.’

‘Lord Compton.’

She stepped inside, then closed and bolted the door. She leaned her back against it, listening for his retreating footsteps. She had the strangest feeling that he had lingered, waiting to hear the bolt slide home.

Imagination. He had no real reason to care if she was safe or not, even if he was a man who liked to control the lives of those around him. Besides, she would never be safe until she dealt with her persecutor.

Once that occurred, she would also be free of His Lordship’s unsettling presence. He was far too domineering, too strict in his notions with regard to his daughters, for her liking. She could not help but be sorry for the poor little motherless mites.

Perhaps that was what they needed. A mother.

A handsome and wealthy man like Lord Compton ought to have no trouble finding a wife. A little stab of something pierced her heart. What, was she jealous of this unknown female and future wife? Surely not?

As she knew to her cost, good looks and wealth did not guarantee happiness.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.