скачать книгу бесплатно

Remarks about her future husband continue, and they are calm, sensible, one could say respectful. There is, however, an entry describing a day in her married life. I shall wake up in that comfortable bed beside him, when the maid comes in to do the fire. Just as his wife did. Then I will kiss him and I will get up to make the coffee, since he likes my coffee. Then I shall kiss him when he goes downstairs to the shop. Then I shall give the girl orders. At last I will go to the room he says I can have for myself and I shall paint. Oils if I like. I will be able to afford anything I like in that line. He usually doesn’t come to the midday meal, so I shall ignore it and walk in the gardens and make conversation with the citizens, who are longing to forgive me. Then I shall play the piano a little, or my flute. He has not heard the music I am writing these days. I don’t think he would like it. Dear Philippe, he is so warmhearted. He had tears in his eyes when thedog was sick. He will come in for supper and we will eat soup. He likes my soup, he likes how I cook. Then we will talk about his day. It is interesting, the work he does. Then we will talk about the newspapers. We shall often disagree. He certainly does not admire Napoleon! He goes to bed early. That will be the hardest, to be shut up in a house all night.

Not once is there a suggestion of a financial calculation. Yet she was quite alone in the world. Her mother had been killed in the Mount Pelée earthquake, having gone to visit a sister living at St Pierre, which was destroyed. It is not recorded whether Julie ever asked her father for help.

A week before the mayor, who was an old friend of Philippe’s, was to marry them at the town hall, she drowned herself in the pool where gossips said she had killed her baby. They did not believe she had killed herself. Why should she, now that all her problems were solved? Nor had she slipped and fallen, which was what the police decided. Absurd! – when she had been jumping around those woods for years, like a goat. No, she was murdered, and probably by a disappointed lover no one knew about. Living all by herself miles from any decent people, she had been asking for something of the sort.

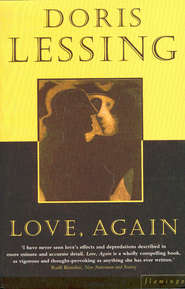

There were suitable condolences for the citizen who had lost his love, for no one could doubt he adored her, but people said he was well out of it. The gendarmes collected up her papers, her sketches, her pictures, a good deal of sheet music, and for lack of a better idea put it all into a big packing case that went to stand in the cellar of the provincial museum. Then, in the 1970s, Rémy’s descendants found some of her music among their papers, were pleased with it, remembered there was a packing case in the museum, found more music there, and got it played at a local summer festival. That is where the Englishman Stephen Ellington-Smith heard it. As music lovers will know, Julie Vairon quickly became recognized as a composer unique in her time, an original, and people are already using the word great.

But she was not only a musician. The artistic world admires her. ‘A small but secure niche…’ is how she is currently evaluated. Some people think she will be remembered for her journals. Excerpts appeared in both France and England, and were at once praised: very much to the taste of this time. Three volumes of her journals were published in France, and one volume (the three abridged) in Britain, where no one disagreed with the French claim that she deserves to stand on the same shelf as Madame de Sévigné. But some people have too many talents for their own good. Perhaps better if she had been an artist with that modest sensitive unpretentious talent so becoming in women. Which brings us to the feminists for whom she is a contentious sister. For some she is the archetypal female victim, while others identify with her independence. And as a musician, so one critic complained, ‘the trouble is one doesn’t know how to categorize her.’ All very well to say now how modern she is, but her music was not of her time. She came from the West Indies, people remind each other, where there is all that loud and disturbing music and it was ‘in her blood’. No one forgets that ‘blood’, an asset now, if not then. No wonder her rhythms are not of Europe. But then, they aren’t African either. To add to the problem, her music had two distinct phases. The first kind is not hard to understand, though where it could have come from certainly is: nearest to it is the trouvère and troubadour music of the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries. But that music was not available in Julie’s time, as it is now, in recordings of arrangements made using the instruments of then and re-created from difficult-to-decipher manuscripts. There are ways of bringing that old music back to life. One tradition of Arab music has changed little in all those centuries from what was taken to Spain, whence it came to southern France and inspired the singers and musicians who wandered from castle to castle, court to court, with instruments that were the ancestors of the ones we know. Yet when music has to be inferred, recreated, ‘heard’, the interpretation of an individual has to be at least in part an original inspiration. The words of the Countess Dié are as she sang them, but exactly how did she sing them? Did Julie see old manuscripts somewhere? We all know the most unlikely things do happen. Where? Did the Rostand family have ancient manuscripts in their possession? The trouble with this interesting theory – which postulates that this ancestor-loving, music-loving clan were so careless with a treasure from the past that they did not recognize its influences on Julie – is that Julie wrote that kind of music before knowing the family, for her songs of that time were fed by her grief over losing Paul. One may speculate harmlessly that among those solid middle-class families whose daughters she taught was one with an ancient chest full of…it is possible. Very well, then, how did this kind of singing come into her mind, living in her hilly solitude? What was she hearing, listening to? It was certain there were the sounds of running and splashing water, the noise of cicadas and crickets, owls and nightjars, and the high thin scream of a hawk on its rocky heights, and the winds of that region, which whine drily through hills where the troubadours went, making their singular music. There are those who say fancifully that she was visited by their essences during those long evenings alone, composing her songs. A music lover actually played them at a concert of trouvère and troubadour music, and everyone marvelled, for she could have been one of them. So that was her ‘first phase’, hard to explain but easy to listen to. Her ‘second phase’ was different, though there was a short period when the two kinds of music were in an uneasy alliance. Oil and water. Nothing African about the new phase. Long flowing rhythms go on, and very occasionally a primitive theme appears, if by that is meant sounds that remind one of dancing, of physical movement. But then it becomes only one of several themes weaving in and out, rather as the voices in late medieval music make patterns where no one voice is more important than another. Impersonal. Perhaps it is that which disturbs. The music of her ‘troubadour’ period complains right enough, but formally, within the limits of a form (like the fado or, for that matter, like the blues) which always sets bounds to the plaint of a little individual calling out for compassion, for surcease – for love. Her late music, cool and crystalline, could have been written by an angel, as a French critic said, but another riposted, No, by a devil.

It is hard, listening to her late music, to match it with what she said of herself in her journal, and with her self-portraits. Just before she threw herself into the pool, because that sensible marriage ‘lacked conviction’, she drew in pastels a wreath of portraits of herself, a satirical echo of those garlands of little cherubs or angels to be found on greeting cards. The sequence begins at top left with a pretty, wispy baby who is staring with intelligent black eyes straight back at the viewer – at, it must be remembered, Julie, as she worked. Next, the delightful little girl, her white muslin dress, the pink ribbons, vigorous black curls, and a smile that both seduces and mocks the viewer. Then an adolescent girl, and she is the only one who does not look directly back out of the picture. She is half turned away, with a proud poised profile, like an eaglet. Nothing comfortable about this girl, and one is glad to be spared her eyes, bound to demand strong reactions and sympathies. At the bottom, a spray of conventionalized leaves to match a bow of white ribbon at the top. At bottom right, opposite the eaglet, a young woman, seen as the apogee of this life, its achievement: she is not unlike Goya’s Duchess of Alba, but prettier, with black curls, a fresh vigorous figure, and black bold amused eyes, forcing you to stare back into them. On the opposing side to the adolescent girl, in her way matching or commenting on her, is a coolly smiling woman in her early thirties, handsome and composed, nothing remarkable about her except for the thoughtful gaze, which holds you until: Very well, then, what is it you want to say? There is a black line drawn between this portrait and the next two: two stages of her life she chose not to live. A plump middle-aged woman sits with folded hands, eyes lowered. All the energy of the picture is in a yellow scarf over her grey hair: she could be any woman of fifty-five. The old woman is only an old woman. There is no individuality there, as if Julie could not imagine herself old or did not care enough to think herself into being old. And having drawn that emphatic black line, she had walked out of her house through the trees and stood – for how long? – on the edge of the river, and then jumped into a pool full of sharp rocks.

This was just before the First World War, which so rapidly and drastically changed the lives of women. Supposing she had not jumped, decided to live?

Before jumping she put her pictures, her music, her journals, into tidy heaps. She did not seem to have destroyed anything, probably thought: Take it or leave it. She did write a helpful note for the police, telling them where to look for her body.

Oblivion, for three-quarters of the century. Then the summer recital in Belles Rivières where her music was played for the first time. Shortly after that, her work was included in an exhibition of women artists in Paris, which came successfully to London. A television documentary was made. A romantic biography was written by someone who had either not read the journals or decided to take no notice of them.

This was where Sarah Durham had entered the story. She read the English version of the journals, thought it unsatisfactory, sent to Paris for the French edition, and found herself captivated by Julie to the extent that she was actually making a draft of a play before discussing it with the other three. They were as intrigued as she was. Afterwards no one could remember who had suggested using Julie’s music; this kind of creative talk among people who work together is very much more than the sum of its parts. They could not stop talking about Julie. She had taken over The Green Bird. Sarah did another draft, with music. This was shown to potential backers, and at once Julie Vairon began to escalate. Then another play arrived, written by Stephen Ellington-Smith, who had done so much to ‘discover’ and then ‘promote’ Julie Vairon: ‘Julie’s Angel’.

They all read this new play, which was romantic, not to say sentimental, and no one would have given it another thought had Patrick not demanded a special meeting. Present were Sarah, Mary Ford, Roy Strether, Patrick Steele – the Founding Four. And, too, Sonia Rogers, an energetic redhead who was being ‘tried out’. They were still saying that she was being tried out when it was evident she was a fixture, because no one wanted to admit an era was over. Why Sonia? Why none of the other hopefuls who worked in and around the theatre, sometimes without payment or for very little? Well, it was because she was there. She was everywhere, in fact. ‘Turn the stone and there you find her,’ jested Patrick. She had come in as a ‘temp’ and had at once become indispensable. Simple. She was at this meeting because she had come into the office for something and was invited to stay. She perched on the top of a filing cabinet as if ready to fly away at one cross word.

Patrick opened fire with ‘What’s the matter with Stephen Whatsit’s play? It just needs a bit of tightening, that’s all.’

Mary sang, ‘ “She was poor but she was honest, victim of a rich man’s whim”.’

Roy said, ‘Two rich men, to be accurate.’

Sarah said, ‘Patrick, these days you simply can’t have a play with a woman as a victim – and that’s all.’

Patrick said, sounding, as he did so often, trapped, betrayed, isolated, ‘Why not? That’s what she was. Like poor Judy. Like poor Marilyn.’

‘I agree with Sarah,’ said Sonia. ‘We couldn’t have a play about Judy. We couldn’t do Marilyn – not just victims and nothing else. It’s not on.’

There was a considerable pause, of the kind when invisible currents and balances shift. Sonia had spoken with authority. She had said We. She wasn’t thinking of herself as temporary, on trial. Right, the Founding Four were thinking. And now that’s it. We have to accept it.

They all knew what each of the others was thinking. How could they not? They did not need even to exchange glances, or grimaces. They were feeling, were being made to feel, faded, shabby – past it. There sat this Sonia, as bright and glossy as a lion cub, and they were seeing themselves through her eyes.

‘I agree absolutely,’ said Mary, finally, assuming responsibility for the moment. And her smile at Sonia was such that the young woman showed her pleasure with a short triumphant laugh, tossing her fiery head. ‘They wouldn’t do an opera about Madame Butterfly now.’ Mary went on.

‘Everyone goes to see Madame Butterfly,’ said Patrick.

‘Everyone?’ said Sonia, making a point they were meant to see was a political one.

‘How about Miss Saigon?’ said Patrick. ‘I’ve read the script.’

‘What’s it about?’ asked Sonia.

‘The same plot as Madame Butterfly,’ said Patrick. ‘You talk your way out of that one, Sarah Durham.’

‘It’s a musical,’ said Sarah. ‘Not our audience.’

‘Disgraceful,’ said Sonia. ‘Are you sure, Patrick?’

‘Absolutely.’

Patrick pressed his attack. ‘Then how about the Zimbabwe play? I don’t remember anyone saying it should be a musical.’

The Zimbabwe play, by black feminists, was about a village girl who longed to live in town, just like everyone else in Zimbabwe, but there is unemployment. Her aunt in Harare says no, her house is already over-full. This precipitates a moral storm in the village, because the aunt’s refusal is a break with the old ways, when the more fortunate members of a family had to keep any poor relation who asked. But the aunt says, I have already got twenty people in my house, with my children and my parents and I’m feeding everyone. She is a nurse. The village girl catches the eye of a local rich man, the owner of a lorry service. She gets pregnant. She kills the child. Everyone knows, but she is not prosecuted. She becomes an amateur prostitute. She never thinks of herself as one: ‘This time the man will love me and marry me.’ Another baby is left on the doorstep of the Catholic mission. She gets AIDS. She dies.

‘I saw it,’ said Sonia. ‘It was good.’

‘But that was all right, because she was black?’ said Patrick, and laughed aloud at the political minefield he had invited them into.

‘Let’s not start,’ said Mary. ‘We’ll be here all night.’

‘Right,’ said Patrick, having made his point.

‘It’s too late anyway,’ said Roy, summing up, as he generally did. Calm, large, unflappable, one of the world’s natural arbiters. ‘We’ve already agreed on Sarah’s play.’

‘But,’ Sonia directed them, ‘I do think we should at least remember that it is the story of girls all over the world. As we sit here. Hundreds of thousands. Millions.’

‘But it’s too late,’ said Roy.

Mary remarked. ‘I don’t think the French are in on it because they like the idea of a good cry. They don’t see it as a weepy. When I talked to Jean-Pierre on the phone yesterday about the publicity, he said Julie was born out of her time.’

‘Well, of course,’ said Sarah.

‘Jean-Pierre says they see her as an intellectual, in their tradition of female bluestockings.’

‘In other words,’ said Roy, ending the meeting by standing up, ‘we shouldn’t be having this conversation at all.’

‘What about the American sponsors?’ demanded Patrick. ‘What have they agreed to? I bet not a French bluestocking.’

‘They bought the package,’ said Sarah.

‘I can tell you this,’ said Patrick. ‘If you did Stephen Whatsit’s play there wouldn’t be a dry eye in the house.’

As Mary and Roy went banging off down the wooden stairs, they sang, ‘“She Was Poor but She Was Honest”,’ and Patrick actually had tears in his eyes. ‘For goodness sake!’ said Sarah, and put her arms around him. As people did so often: There there! He complained they patronized him, and they said, But you need it, with your wounded heart always on view. All this had been going on for years. But things had changed…Sonia wasn’t going to spoil him. Now, at the foot of the stairs, she looked critically at Patrick who – always ornamental, and even bizarre – was today like a beetle, in a shiny green jacket, his black hair in spikes. But Sonia, in the height of fashion, wore black full Dutch-boy trousers, a camouflage T-shirt from army surplus and over it a black lace bolero from some flea market, desert boots, a jet Victorian choker necklace, many rings and earrings. Her hair, in a variation of a 1920s shingle, was in a tight point at the back, and in front in deeply curving lobes, like a spaniel’s ears. But her hair was seldom the same for more than a day or two. Her get-up did not please Patrick. He had already been heard shrilly criticizing her for lack of chic. ‘Being a freak isn’t smart, love,’ he had said. To which she had replied, ‘And who’s talking?’

Sarah did not go to bed on the night before she was due to meet Stephen Ellington-Smith. For one thing, she had not finished cleaning until three in the morning. Then she decided to do the programme notes after all. Then she reread Julie’s journals, preparing herself for what she believed would be a fight with Julie’s Angel.

‘Look,’ she imagined herself saying, ‘Julie never saw herself as a victim. She saw herself as having choice. Until 1902 and her mother’s death, she could have gone home to Martinique. Her mother actually wrote saying she was welcome any time. There’s even a rather silly letter from her half-brother, who took over the estate when the father died, making jokes about their relationship; it was insulting in a sort of schoolboy way. He said the father had told him to “look after” Julie. But she didn’t reply. She wondered whether she should be a prostitute – don’t forget this was the time of les grandes horizontales. But she said she had no taste for luxury, and that did seem to be essential for a highclass tart. She was offered a job as a chanteuse in a nightclub in Marseilles, but she said it would be too emotionally demanding, she would have no time for her music and her painting. Anyway, she hated provincial towns. She did actually have the chance of going to Paris in a touring company as a singer. But this was nothing like her dreams of Paris. She said in her journal, If Rémy asked me to go to Paris and live with him there…we could live quietly, we could have real friends…The underline there says everything, I think. She goes on. Of course it is out of the question, though I saw him with his wife at the fête. It is clear they do not love each other. She was invited to go as governess in a lawyer’s household in Avignon: he was a widower. Several men wanted to set her up in Nice or Marseilles as a mistress. These offers were merely recorded, as she might have written, It was hot today, or, It was cold.

‘We could easily present Julie in terms of what she refused. And what did she actually choose? A little stone house in the forest. “The cow-byre”, as the citizens contemptuously called it. She chose to live alone, paint and draw and compose her music and, every night of her life, write a commentary on it.

‘Yes, I agree it is not easy to make of this a riveting drama. Not easy even if we keep the form you have chosen. Act One: Paul. Act Two: Rémy. Act Three: Philippe. Yes, you could argue that she did write, I don’t think I could bear to move away from my little house where everything speaks to me of love. As George Sand might have written. But don’t forget she went on, I live here exactly as my mother did in her house. The difference is that she has been kept all her life. By one man – my father. She always loved him and never had choice. She could not leave his estate because if she did she could have earned her living only as a brothel-keeper (like her mother and her grandmother, or so she hinted). Or as an ordinary prostitute, or perhaps as a housekeeper. What were her accomplishments? She could cook. She could dress. She knew about plants and herbs. Presumably she knew about love but we never discussed love, that is, the making of it, because she destined me to be a young lady and she didn’t want to raise thoughts in my mind about her, about what she is really like (and that is in itself so touching it could almost break my heart, because how else could I have defined myself, what I am, if not by understanding her?). But I am very much afraid, if we sat alone and talked like women, I would hear her say, I live here in this house because everything in it and near it reminds me of love. And included in this love would be memories of shadows of great trees on her walls, and in the mirror of her sitting room and on the ceilings of her bedroom, and the damp, the everlasting humidity, and the heavy smell of flowers and of wet vegetation, and a smell something like the wet fur of animals that filled the house when it rained. But thefact is, my mother could not have left her house and her life even if she wanted to, but I can leave here at any time.

‘Where in all this do we see the victim?’

It was not that she was afraid of any financial consequences of refusing his play, because he had written, ‘I am sure it goes without saying that my support for the play will not be in any way affected if you all decide my little attempt is not good enough.’

He was already at a table in a restaurant she was relieved to find was not one of the currently fashionable ones. A large, rather dark, old-fashioned room, and quiet. He was at first glance a country gentleman. As she advanced towards him she reflected that it was surely remarkable that when she returned to the office and answered Mary Ford’s query, ‘What’s he like?’ with ‘He’s a country gentleman, old style’ – then Mary would at once know what she meant. Her parents, or Mary Ford’s, her grandparents or Mary’s, would not at once be able to ‘place’ many people in today’s Britain, but they would know Stephen Ellington-Smith at a glance. He was a man of about fifty, large but not fat. He was big-framed and, authoritatively but casually, seemed to take up a lot of space. His face was blond and open: green-eyed, sandy-lashed; and his hair, once fair, was greying. His clothes were as you’d expect: but Sarah found herself automatically making notes for the next time they needed to fit out such a character in a play. Their essence, she decided, was that they would be unnoticeable if he was stalking a deer. His mildly checked brownish-yellow jacket was like a zebra’s coat in that it was designed to merge.

He watched her come towards him, rose, pulled out a chair. His inspection, she knew, was acute, but not defensive. She felt he liked her, but then, people on the whole tended to.

‘There you are,’ said he. ‘I must say you are a relief. I don’t know quite what I expected, though.’ Then, before they had even settled themselves, he said, ‘I really do have to make it clear that I’m not going to mind if you people have decided against my play. I’m not a playwright. It was a labour of love.’

He was saying this as one does to clear the ground before another – the real problem is faced. And she was thinking of a conversation in the office. Mary had remarked, ‘All the same, it’s a funny business. He’s been involved with Julie Vairon for a good ten years one way or another. What’s in it for him?’ Quite so. Why should this man, ‘A regular amateur of the arts, old style, you know’ – so he had been described by the Arts Council official who had suggested approaching him as a patron – have been involved with that problematical Frenchwoman for a decade or more? The reason was almost certainly the irrational and quirky thing that is so often the real force behind people and events, and often not mentioned, or even noticed. This was what Mary Ford had been hinting at. More than hinting. She had said, ‘If we’re going to have problems with him, let’s have them out in the open right from the beginning.’ ‘What sort of problems do you expect?’ Sarah had asked, for she respected Mary’s intuition. ‘I don’t know.’ Then she sang, to the tune of ‘Who Is Sylvia’, ‘Who is Julie, what is she…’

They began by talking practicalities. There was the difficulty that began Julie Vairon’s career. The play was to have gone on in London at The Green Bird, one of three planned for the summer season. By chance, Jean-Pierre le Brun, an official from Belles Rivières, heard from the Rostand family, which had been very co-operative, that a play was imminent, and he flew to London to protest. How was it that Belles Rivières had not been consulted? The truth was, the Founding Four had not thought of it, but that was because they had not seen the piece as ambitious enough to involve the French. Besides, Belles Rivières did not have a theatre. And, as well, Julie Vairon was in English. Jean-Pierre had accepted that the English had been quicker to see the possibilities of Julie, and no one wanted to deny them that honour. There was no question of taking Julie Vairon away from The Green Bird. That was hardly possible, at this stage. But he was genuinely and bitterly hurt that Belles Rivières had been excluded. What was to be done? Very well, the English version could be used for a run in France. Yes, unfortunately it had to be admitted that if tourists were attracted, then they would be more likely to speak English than French. And besides, so many of the English themselves were settled in the area…he shrugged, leaving them to decide what he thought of this state of affairs.

So it was decided. And what about the money? For The Green Bird could not finance the French run. No problem, cried Jean-Pierre; the town would provide the site, using Julie’s own little house in the woods – or what was left of it. But Belles Rivières did not have the resources to pay for the whole company for a run of two weeks. It was at this point that an American patron came in, to add his support. How had he heard of this, after all, pretty dicey proposition? Someone in the Arts Council had recommended it and this was because of Stephen’s reputation.

At this point, mutual support and helpfulness was being expressed mostly in photographs back and forth, London to Belles Rivières, London to California, Belles Rivières to California. It turned out that there was already a Musée Julie Vairon in Belles Rivières. Her house was visited by pilgrims.

Stephen was disturbed. ‘I wonder what she’d think of so many people in her forest. Her house.’

‘Didn’t we tell you we were going to use her house for the French run? Didn’t you see the promotional material?’

‘I suppose I hadn’t really taken it in.’ He seemed to be debating whether to trust her. ‘I even felt bad about writing that play – invading her privacy, you know.’ Then, as she found herself unable to reply to this, for it was a new note, and unexpected, he added abruptly, thrusting out his chin small-boy style, ‘You have understood, I am sure, that I am hopelessly in love with Julie?’ Then gave a helpless, painful grimace, flung himself back in his chair, pushed away his plate, and looked at her, awaiting a verdict.

She attempted a quizzical look, but his gesture was impatient. ‘Yes, I am besotted with her. I have been since I first heard her music at that festival. In Belles Rivières, you know. She’s the woman for me. I knew that at once.’

He was trying to sound whimsical but was failing.

‘I see,’ she said.

‘I hope you do. Because that’s the whole point.’

‘You aren’t expecting me to say anything boring, like, She’s been dead for over eighty years?’

‘You can say it if you like.’

The silence that followed had to accommodate a good deal. It was not that his passion was ‘crazy’ – that portmanteau word, but that he was sitting there four-square and formidable, determined that she should not find it so. He waited, apparently at his ease because he had made his ultimatum, and he even glanced about at this familiar scene of other eaters, waiters, and so on, but she knew that here, at this very point, was what he was demanding in return for his very sizeable investment. She had to accept him, his need.

After a time she heard herself remark, ‘You don’t like her journals very much, do you?’

At this he let out a breath. It would have been a sigh if he had not been measuring it, checking it, even, for too much self-revelation. He shifted his legs abruptly. He looked away, as if he might very well get up and escape and then made himself face her again. She liked him very much then. She liked him more and more. It was because she felt at ease with him, absolutely able to say anything.

‘You’ve put your finger on…no, I don’t. No, when I read her journals I feel – shut out. She slams a door in my face. It’s not what I…’

‘What you are in love with?’

‘I don’t think I’d like that cold intelligence of hers directed at me.’

‘But when one is in love one’s intelligence does go on, doesn’t it? Commenting on –’

‘On what?’ he cut in. ‘No, if she’d been happy she’d never have written all that. All that was just…self-defence.’

At this she had to laugh, because of the enormity of his dismissal of – as far as she was concerned – the most interesting aspect of Julie.

‘Oh all right, laugh,’ he said grumpily, but with a smile. She could see he did not mind her laughing. Perhaps he even liked it. There was something about him of a spreading, a relaxation, as if he had held a breath for too long and was at last able to let it go. ‘But you don’t understand, Sarah – I may call you Sarah? Those journals are such an accusation.’

‘But not of you.’

‘I wonder. Yes, I do, often. What would I have done? Perhaps she would have written of me as she did about Rémy. I represented to him everything he had ever dreamed about when he hoped to be larger than his family, but in the end he was not more than the sum of his family.’

‘And is that what she represents to you? An escape from your background?’

‘Oh no,’ he said at once. ‘To me she represents – well, everything.’

She could feel her whole self rejecting this mad exaggeration. Her body, even her face, was composing itself into critical lines, without any directing intention from her intelligence. She lowered her eyes. But he was watching her – yes, she already knew that close, intelligent look – and he knew what she was feeling, for he said, ‘Please don’t tell me you don’t know what I mean.’

‘Perhaps,’ she said cautiously, ‘I have decided to forget it.’

‘Why?’ he enquired, not intending flattery. ‘You are a good-looking woman.’

‘I am a good-looking woman still,’ said she. ‘I am still a good-looking woman. Quite so. That’s it. I haven’t been in love for twenty years. Recently I’ve been thinking about that – twenty years.’ As she spoke she was amazed that she was saying to this stranger (but she knew he was not that) things she had never said to dear and good friends, her family – that is what they were – at the theatre. She put on the humour and maternal style that seemed more and more her style: ‘And what was it all about, I wonder now, all that…absurdity?’

‘Absurdity?’ And he let out that grunt of laughter that means isolation in the face of wilful misunderstanding.

‘All that anguish and lying awake at night,’ she insisted, forcing herself to remember that indeed she had done all that. (It occurred to her she had not even acknowledged, for years, that she had done all that.) ‘Thank God it can never happen to me again. I tell you, getting old has its compensations.’ Here she stopped. It was because of his acute examination of her. She felt at once that her voice had rung false. She was blushing – she felt hot, at any rate. He was, there was no doubt, a handsome man, or had been. He was a pretty good proposition even now. Twenty years ago perhaps…and here she smiled ironically at him, for she knew her hot cheeks were making confessions. She went on, however, actually thinking that if he could be so brave, then so could she. ‘What I think now is, I was in love too often.’

‘I’m not talking about the little inflammations.’

Again she had to laugh. ‘Well, perhaps you are right.’ Right about what? – and she could see he was finding the phrase, as she did the moment it was out, a bromide, dishonest. ‘But why do we assume it always means the same thing to everyone – being in love? Perhaps “little inflammations” is accurate enough, for a lot of people. Sometimes when I see someone in love I think that a good screw would settle it.’ Here she took from him, as she had expected to, a surprised and even hard look at the ugly term, which she had used deliberately. Women who are ‘getting on’ often have to do this. One minute (so it feels) they are using the language of our time (ugly, crude, honest), and in the next, they have become, or feel they soon will if they don’t do something about it, ‘little old ladies’, because the younger generation have begun to censor their speech, as if to children. But, she thought, critical of herself, there is no need to take up stances with this man.

He said, after a long pause, while he examined her, ‘You’ve simply decided to forget, that’s all it is.’

She conceded, ‘Very well, then, I have. Perhaps I don’t want to remember. If a man had ever been everything to me – that’s what you said, everything…but I did have a very good marriage. But everything…let’s talk about your play, Stephen.’ And she deliberately (dishonestly) let this look as if she didn’t want to talk about her dead husband.

‘All right,’ he agreed, after a pause. ‘But it’s not important. I don’t really mind about it. Scrap it.’

‘Wait. I’m going to keep a good bit of it. The dialogue is good.’ This was not tact. His dialogue in parts was better than hers. Now she knew why. ‘Do you realize you have made Rémy the focus of everything? The real love? What about Paul? After all, she did run away to France with him.’

‘Rémy was the love of her life. She said so herself. It’s in her journals.’

‘But she didn’t get into her stride with the journals until after Paul ditched her. Suppose we had a day-by-day record of her feelings for Paul, as we have for Rémy?’ He definitely did not like this. ‘You identify with Rémy – and it is your own background. Minor aristocracy?’

‘Well, perhaps.’

‘And you’ve hardly mentioned the son of her worthy printer. Julie and Robert took one look at each other and, quote, If you have a talent for the impossible, then at least recognize it. After that, she killed herself. It seems to me the printer’s son could easily have been as important as Rémy.’

‘It seems to me you want to make her a kind of tart, falling in love with one man after another.’

She couldn’t believe her ears. ‘How many women have you been in love with?’

Obviously he couldn’t believe his. ‘I don’t really see the point of discussing the double standard.’