Полная версия

Полная версияThe Comic Latin Grammar: A new and facetious introduction to the Latin tongue

The accusative case follows the verb, as a bailiff follows a debtor, a bull-dog a butcher, or a round of applause a supernatural squall at the Italian Opera. It answers to the question Whom? or What? as, Whom do you laugh at? (behind his back) Derideo magistrum – I laugh at the master.

The vocative case is known by calling, or speaking to; as, O magister – O master; an exclamation which is frequently the consequence of shirking out, making false concords or quantities, obstreperous conduct in school, &c.

The ablative case is known by certain prepositions, expressed or understood; as Deprensus magistro – caught out by the master. Coram rostro– before the beak. The prepositions, in, with, from, by, and the word, than, after the comparative degree, are signs of the ablative case. In angustiâ – in a fix. Cum indigenâ – with a native. Ab arbore – from a tree. A rictu – by a grin. Adipe lubricior – slicker than grease.

GENDERS AND ARTICLES

The genders of nouns, which are three, the masculine, the feminine, and the neuter, are denoted in Latin by articles. We have articles, also, in English, which distinguish the masculine from the feminine, but they are articles of dress; such as petticoats and breeches, mantillas and mackintoshes. But as there are many things in Latin, called masculine and feminine, which are nevertheless not male and female, the articles attached to them are not parts of dress, but parts of speech.

We will now, with our readers’ permission, initiate them into a new mode of declining the article hic, hæc, hoc. And we take this opportunity of protesting against the old and short-sighted system of teaching a boy only one thing at a time, which originated, no doubt, from the general ignorance of everything but the dead languages which prevailed in the monkish ages. We propose to make declensions, conjugations, &c., a vehicle for imparting something more than the mere dry facts of the immediate subject. And if we can occasionally inculcate an original remark, a scientific principle, or a moral aphorism, we shall, of course, think ourselves sufficiently rewarded by the consciousness – et cætera, et cætera, et cætera.

Masc. hic. Fem. hæc. Neut. hoc, &cThe nominative singular’s hic, hæc, and hoc, —Which to learn, has cost school boys full many a knock;The genitive ’s hujus, the dative makes huic,(A fact Mr. Squeers never mentioned to Smike);Then hunc, hanc, and hoc, the accusative makes,The vocative – caret – no very great shakes;The ablative case maketh hôc, hac, and hôc,A cock is a fowl – but a fowl ’s not a cock.The nominative plural is hi, hæ, and hæc,The Roman young ladies were dressed à la Grecque;The genitive case horum, harum, and horum,Silenus and Bacchus were fond of a jorum;The dative in all the three genders is his,At Actium his tip did Mark Antony miss:The accusative ’s hos, has, and hæc in all grammars,Herodotus told some American crammers;The vocative here also – caret – ’s no go,As Milo found rending an oak-tree, you know;And his, like the dative the ablative case is,The Furies had most disagreeable faces.Nouns declined with two articles, are called common. This word common requires explanation – it is not used in the same sense as that in which we say, that quackery is common in medicine, knavery in the law, and humbug everywhere – pigeons at Crockford’s, lame ducks at the Stock Exchange, Jews at the ditto, and Royal ditto, and foreigners in Leicester Square – No; a common noun is one that is both masculine and feminine; in one sense of the word therefore it is uncommon. Parens, a parent, which may be declined both with hic, and hæc, is, for obvious reasons, a noun of this class; and so is fur, a thief; likewise miles, a soldier, which will appear strange to those of our readers, who do not call to mind the existence of the ancient amazons; the dashing white sergeant being the only female soldier known in modern times. Nor have we more than one authenticated instance of a female sailor, if we except the heroine commemorated in the somewhat apocryphal narrative – Billy Taylor.

Nouns are called doubtful when declined with the article hic or hæc – whichever you please, as the showman said of the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon Bonaparte. Anguis, a snake, is a doubtful noun. At all events he is a doubtful customer.

Epicene nouns are those which, though declined with one article only, represent both sexes, as hic passer, a sparrow, hæc aquila, an eagle, – cock and hen. A sparrow, however, to say nothing of an eagle, must appear a doubtful noun with regard to gender, to a cockney sportsman.

After all, there is no rule in the Latin language about gender so comprehensive as that observed in Hampshire, where they call every thing he but a tom-cat, and that she.

DECLENSION OF NOUNS SUBSTANTIVE

There are five declensions of substantives. As a pig is known by his tail, so are declensions of substantives distinguished by the ending of the genitive case. Our fear of outraging the comic feelings of humanity, prevents us from saying quite so much about them as our love of learning would otherwise induce us to do. We therefore refer the student to that clever little book, the Eton Latin Grammar, strongly recommending him to decline the following substantives, by way of an exercise, after the manner of the examples there set down. First declension, Genitivo æ. Virga, a rod. – Second, i. Puer, a boy. Stultus, a fool. Tergum, a back. – Third, is. Vulpes, a fox. Procurator, an attorney. Cliens, a client. – Fourth, ûs – here you may have, Risus, a laugh at. – Fifth, ei. Effigies, an effigy, image, or Guy.

The substantive face, facies, makes faces, facies, in the plural.

Although we are precluded from going through the whole of the declensions, we cannot refrain from proposing “for the use of schools,” a model upon which all substantives may be declined in a mode somewhat more agreeable, if not more instructive, than that heretofore adopted.

Exempli GratiâMusa musæ,The Gods were at tea,Musæ musam.Eating raspberry jam,Musa musâ,Made by Cupid’s mamma,Musæ musarum,Thou “Diva Dearum.”Musis musas,Said Jove to his lass,Musæ musis.Can ambrosia beat this?DECLENSIONS OF NOUNS ADJECTIVE

Some nouns adjective are declined with three terminations – as a pacha of three tails would be, if he were to make a proposal to an English heiress – as bonus, good– tener, tender. Sweet epithets! how forcibly they remind us of young Love and a leg of mutton.

Bonus, bona, bonum,Thou little lambkin dumb,Boni, bonæ, boni,For those sweet chops I sigh,Bono, bonæ, bono,Have pity on my woe,Bonum, bonam, bonum,Thou speak’st though thou art mum,Bone, bona, bonum,“O come and eat me, come,”Bono, bonæ, bono,The butcher lays thee low,Boni, bonæ, bona,Those chops are a picture, – ah!Bonorum, bonarum, bonorum,To put lots of Tomata sauce o’er ’emBonis – Don’t, miss,Bonos, bonas, bona,Thou art sweeter than thy mamma,Boni, bonæ, bona,And fatter than thy papa.Bonis, – What bliss!In like manner decline tener, tenera, tenerum.

Unus, one; solus, alone; totus, the whole; nullus, none; alter, the other; uter, whether of the two – make the genitive case singular in ius and the dative in i.

RIDDLESQ. In what case will a grain of barley joined to an adjective stand for the name of an animal?

A. In the dative case of unus – uni-corn.

Uni nimirum tibi rectè semper erunt res.

Hor. Sat. lib. ii. 2. 106.

Q. Why is the above verse like all nature?

A. Because it is an uni-verse.

The word alius, another, is declined like the above-named adjectives, except that it makes aliud, not alium, in the neuter singular.

The difference of unus from alius, say the London commentators, like that of a humming-top from a peg-top, consists of the ’um.

N.B. Tu es unus alius, is not good Latin for “You’re another,” a phrase more elegantly expressed by “Tu quoque.”

There are some adjectives that remind us of lawyer’s clerks, and, by courtesy, of linen-drapers’ apprentices. These may be termed articled adjectives; being declined with the articles hic, hæc, hoc, after the third declension of substantives – as tristis, sad, melior, better, felix, happy.

It is not very easy to conceive any thing in which sadness and comicality are united, except Tristis Amator, a sad lover.

Melior is not better for comic purposes. Felix affords no room for a happy joke.

Decline these three adjectives, and others of the same class, according to the following rules:

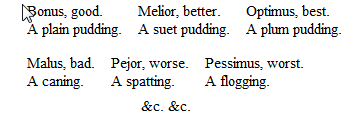

If the nominative endeth in is or er, why, sir,The ablative singular endeth in i, sir;The first, fourth, and fifth case, their neuter make e,But the same in the plural in ia must be.E, or i, are the ablative’s ends, – mark my song,While or to the nominative case doth belong;For the neuter aforesaid we settle it thus:The plural is ora; the singular us.If than is, er, and or, it hath many more enders,The nominative serves to express the three genders;But the plural for ia hath icia and itia,As Felix, felicia – Dives, divitia.COMPARISONS OF ADJECTIVES

Comparisons are odious —

Adjectives have three degrees of comparison. This is perhaps the reason why they are so disagreeable to learn.

The first degree of comparison is the positive, which denotes the quality of a thing absolutely. Thus, the Eton Latin Grammar is lepidus, funny.

The second is the comparative, which increases or lessens the quality, formed by adding or to the first case of the positive ending in i. Thus the Charter House Grammar, is lepidor – funnier, or more funny. – The third is the superlative, which increases or diminishes the signification to the greatest degree, formed from the same case by adding thereto, ssimus. Thus the Comic Latin Grammar is lepidissimus, funniest, or most funny. A Londoner is acutus, sharp, or ’cute, – a Yorkshireman acutior, sharper, or more sharp, ’cuter or more ’cute – but a Yankee is acutissimus – sharpest, or most sharp, ’cutest or most ’cute, or tarnation ’cute.

Enumerate, in the manner following, with substantives, the exceptions to this rule, mentioned in the Eton Grammar.

Adjectives ending in er, form the superlative in errimus. The taste of vinegar is acer, sour; that of verjuice acrior, more sour; the visage of a tee-totaller, acerrimus, sourest, or most sour.

Agilis, docilis, gracilis, facilis, humilis, similis, change is into llimus, in the superlative degree.

Agilis, nimble. – Madlle. Taglioni.

Agilior, more nimble. – Jim Crow.

Agillimus, most nimble. – Mr. Wieland.

Docilis, docile. – Learned Pig.

Docilior, more docile. – Ourang-outang.

Docillimus, most docile. – Man Friday.

Gracilis, slender. – A whipping post.

Gracilior, more slender. – A fashionable waist.

Gracillimus, most slender. – A dustman’s leg.

&c. &c.

If a vowel comes before us in the nominative case of an adjective, the comparison is made by magis, more, and maximè, most.

Pius, pious. – Dr. Cantwell.

Magis pius, more pious. – Mr. Maw-worm.

Maximè pius, most pious. – Mr. Stiggins.

Sancho Panza called Don Quixote, Quixottissimus. This was not good Latin, but it evinced a knowledge on Sancho’s part, of the nature of the superlative degree.

OF A PRONOUN

A pronoun is a substitute, or (as we once heard a lady of the Malaprop family say), a subterfuge for a noun.

There are fifteen Pronouns.

Ego, tu, ille,

I, thou, and Billy,

Is, sui, ipse,

Got very tipsy.

Iste, hic, meus,

The governor did not see us.

Tuus, suus, noster,

We knock’d down a coster-

Vester, noster, vestras.

monger for daring to pester us.

To these may be added, egomet, I myself; tute, thou thyself, idem the same, qui, who or what, and cujas, of what country.

DECLENSION OF PRONOUNS

Pronouns concern ourselves so much, that we cannot altogether pass over them; though a hint or two with regard to the mode of learning their declension is all that we can here afford to give. We are constrained now and then to leave out a good deal of valuable matter, for the reason that induced the Dublin manager to omit the part of Hamlet in the play of that name – the length of the performance.

Pronouns may be thus agreeably declined:

Ego, mei, mihi,

Hoist the frog up sky-high.

Tu, tui, tibi,

In Chancery they fib ye.

Ille, illa, illud,

Cows chew the cud.

Is, ea, id,

Always do as you’re bid.

Qui, quæ, quod,

Or else you’ll taste the rod.

Every donkey can decline is, ea, id. We heard one the other day on Hampstead Heath, repeat distinctly

E – o! e – a! e – o!

When you decline quis quæ quid, beware of any temptation to indulge in dirty habits. Eschew pig-tail instead of chewing it. Never have any quid in your mouth, but a quid pro quo.

OF A VERB

A verb is the chief word in every sentence, as Suspendatur per collum, let him be hanged by the neck.

It expresses the action or being of a thing. Ego sum sapiens, I am a wise man. Tu es stultus, thou art a fool. Non hic amice, pernoctas, you don’t lodge here, Mr. Ferguson.

Verbs have two voices, like the gentleman who was singing, a short time since, at the St. James’s Theatre.

The active ending in o– as amo, I love.

The passive ending in or– as amor, I am loved.

In these two words is contained the terrestrial summum bonum – In short, love beats everything – cock-fighting not excepted. Amo! amor! How happy every human being, from the peer to the pot-boy, from the duchess to the dairy-maid, would be to be able to say so.

They would conjugate immediately. Except, however, certain modern political economists of the Malthusian school, who, albeit they are great advocates for the diffusion of learning, are violently opposed to unlimited conjugations.

Of verbs ending in o some are actives transitive. A verb is called transitive when the action passes on to the following noun, as Seco baculum meum, I cut my stick.

Numerous examples of this kind of cutting, which may be called a comic section, are recorded in history, both ancient and modern. Even Hector cut his stick (with Achilles after him) at the siege of Troy. The Persians cut their stick at Marathon. Pompey cut his stick at Pharsalia, and so did Antony at Actium. Napoleon Bonaparte cut his stick at Waterloo.

Other verbs ending in o are named neuters and intransitives. A verb is called intransitive, or neuter, when the action does not pass on, or require a following noun, as curro, I run. Pistol cucurrit, Pistol ran. But to say, “Falstaff voluit currere eum per,” “Falstaff wished to run him through,” would be making a neuter verb, a verb active, and would therefore be Latin of the canine species, or Dog-Latin; so would Meus homo Gulielmus cucurrit caput suum plenum sed contra te homo dic pax, My man William ran his head full but against the mantel-piece. This, it is obvious, will not do after Cicero.

Verbs transitive ending in o become passive by changing o into or, as Secor, I am cut. Cæsar was cut by his friend Brutus in the capitol. “This,” as Antony very judiciously observed on the hustings, “was the most unkindest cut of all,” – much worse, indeed, than any of the similar operations which are daily performed in Regent Street.

Verbs neuter and intransitive are never made passive. We may say, Crepo, I crack, but we cannot say, Crepor, I am cracked.

The ancient heroes appear, from what Homer says, to have got into a way of cracking away most tremendously when they were going to engage in single combat.

Orestes was certainly cracked.

Some verbs ending in or have an active signification – as Loquor, I speak.

Q. Why are such verbs like witnesses on oath?

A. Because they are called “Deponents.”

Of these some few are neuters, as Glorior, I boast.

Cæsar boasted that he came, saw, and overcame. Bald-headed people (like Cæsar) do not, in general, make conquests so easily.

Neuter Verbs ending in or, and verbs deponent, are declined like verbs passive; but with gerunds and supines like verbs active; thus presenting a curious combination of activity and supineness.

There are some verbs which are called verbs personal. A verb personal resembles a mixed group of old maids and young maids, because it has different persons, as Ego irrideo, I quiz. Tu irrides, thou quizzest.

A verb impersonal is like a collection of tombstone angels, or small children; it has not different persons, as tædet, it irketh, oportet, it behoveth.

It irketh to learn Greek and Latin, nevertheless it behoveth to do so.

OF MOODS

Moods in verbs are like moods in man, they have each of them a peculiar expression. Here, however, the resemblance stops. Man has many moods, verbs have but five. For instance, we observe in men the merry mood, the doleful mood, (or dumps), the shy, timid, or sheepish mood, the bold, or bumptious mood, the placid mood, the angry mood, whereto may be added the vindictive mood, and the sulky mood; the sober mood, as contradistinguished from both the serious and the drunken mood; or as blended with the latter, in which case it may be called the sober-drunk mood – the contented mood, the grumbling mood; the sympathetic mood, the sarcastic mood, the idle mood, the working mood, the communicative mood, the secretive mood, and the moods of all the phrenological organs; besides the monitory or mentorial mood, and the mendacious, or lying mood, with the imaginative, poetical, or romantic mood, the compassionate, or melting mood, and many other moods too tedious to mention.

We must not however omit the flirting mood, the teazing or tantalizing mood, the giggling mood, the magging or talkative mood, and the scandalizing mood, which are peculiarly observable in the fair sex.

The moods of verbs are the following:

1. The indicative mood, which either affirms a fact or asks a question, as Ego amo, I do love. Amas tu? Dost thou love?

The long and short of all courtships are contained in these two examples.

2. The imperative mood, which commandeth, or entreateth. This two-fold character of the imperative mood is often exemplified in schools, the command being on the part of the master, and the entreaty on that of the boy – as thus, Veni huc! Come hither! Parce mihi! Spare me! The imperative mood is also known by the sign let– as in the well-known verse in the song Dulce Domum —

“Eja! nunc eamus.”

“Hurrah! now let us be off” – meaning for the vacation. N.B. This mood is one much in the mouth of beadles, boatswains, bashaws, majors, magistrates, slave drivers, superintendents, serjeants, and jacks-in-office of all descriptions – monitors, especially, and præfects of public schools, are very fond of using it on all occasions.

3. The potential mood signifies power or duty. The signs by which it is known are, may, can, might, would, could, should, or ought – as, Amem, I may love (when I leave school). Amavissem, I should have loved (if I had not known better,) and the like.

4. The subjunctive differs from the potential only in being always governed by some conjunction or indefinite word, and in being subjoined to some other verb going before it in the same sentence – as Cochleare eram cum amarem, I was a spoon when I loved – Nescio qualis sim hoc ipso tempore, I don’t know what sort of a person I am at this very time.

The propriety of the above expression “cochleare,” will be explained in a Comic System of Rhetoric, which perhaps may appear hereafter.

5. The infinitive mood is like a gentleman’s cab, because it has no number.

We have not made up our minds exactly, whether to compare it to the “picture of nobody” mentioned in the Tempest, or to the “picture of ugliness,” which young ladies generally call their successful rivals. It may be like one, or the other, or both, because it has no person.

Neither has it a nominative case before it; nor, indeed, has it any more business with one than a toad has with a side pocket.

It is commonly known by the sign to. As, for example – Amare, to love; Desipere, to be a fool; Nubere, to marry; Pœnitere, to repent.

OF GERUNDS AND SUPINES

Ever anxious to encourage the expansion of youthful minds, by as general a cultivation as possible of the various faculties, we beg to invite attention to the following combination of Grammar, Poetry, and Music.

Air. – Believe me if all those endearing young charms. – MooreThe gerunds of verbs end in di, do, and dum,But the supines of verbs are but two;For instance, the active, which endeth in um,And the passive which endeth in u.Amandi, of loving, kind reader, beware;Amando, in loving, be brief;Amandum, to love, if you ’re doom’d, have a care,In the goblet to drown all your grief.Amatum, Amatu, to love and be loved,Should it be your felicitous (?) lot,May the fuel so needful be never removedWhich serves to keep boiling the pot.OF TENSES

In verbs there are five tenses, or times, expressing an action, or affirmation.

1. The present tense, or time. There is no time (or tense) like the present. It expresses an action now taking place. Examples – Act. I love, or am loving. Amo, I am loving. —Pass. I am made drunk, or am drunk. Inebrior, I am drunk.

2. The preterimperfect tense denotes something, or a state of things, partly, but not entirely past. – Examp. I did love or was loving. Amabam, I was loving. I was made drunk an hour ago. Inebriabar, I was made drunk.

3. The preterperfect tense expresses a thing lately done, but now ended. – Examp. I have loved, or I loved. Amavi, I loved. I have been made drunk, or have been drunk. Inebriatus sum, I have been drunk.

4. The preterpluperfect tense refers to a thing done at some time past, but now ended. – Examp. Amaveram, I had loved. Inebriatus eram, I had been drunk.

5. The future tense relates to a thing to be done hereafter, as, Amabo, I shall or will love. Inebriabor, I shall get drunk – say to-morrow.

OF NUMBERS AND PERSONS

Verbs have two numbers. No. 1, Singular, No. 2, Plural.

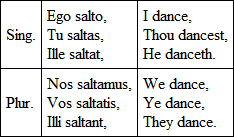

In most matters it is usual to pay exclusive attention to number one. In learning the verbs, however, it is necessary to regard equally number two. – The persons of verbs are generally considered very disagreeable. Verbs have three persons in each number. Thus, for instance, at a dancing academy —

At an academy on Free-knowledge-ical principles – or a Comic Academy.

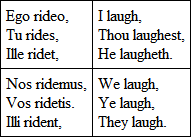

Laughter, too, is very common at other academies, but generally occurs on the wrong side of the mouth. The right sort of laughter (which may be presumed to be on the right side of the mouth), is most frequent about the time of the holidays. What does the song say?

“Ridet annus, prata ridentNosque rideamus.”“The year laughs, the meadows laugh, – suppose we have a laugh as well.”Note– That all nouns are of the third person except Ego, Nos, Tu, and Vos. Hence we see how absurdly the man who drew a couple of donkeys acted in endeavouring to prevail upon us to call the picture “We Three” —Ille, he, – may, perhaps, have been qualified to make a third person in the group, and have “written himself down an ass” with some correctness. Ego, I, and Nos, we, have certainly nothing in common with that animal, and it is to be hoped that neither Tu, thou, nor Vos, ye, can be said to partake of his nature.