Полная версия:

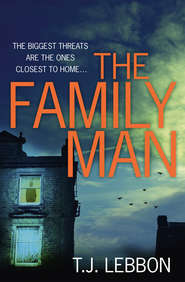

The Family Man: An edge-of-your-seat read that you won’t be able to put down

Dom looked back. The BMW was so close that he expected an impact at any minute. He wasn’t sure what model it was, didn’t know enough about cars to know whether his Focus could outrun it, or at least stay ahead.

‘Dom, hundred metres before the house? More? Less?’

‘Bit more,’ he said.

‘Right. Bend’s coming up in a minute. When I say, goad the hell out of him.’

‘This is crazy,’ Dom said.

‘It’s happening,’ Andy said.

The engines roared. The BMW pressed in closer, surging forward. Andy drifted the Focus to the right, blocking the road.

‘Okay,’ Andy said.

Dom froze for a moment, feeling the unreality of things pressing in close. Then he gave Roadrunner the finger.

Andy swerved them around the bend, wheel juddering in his hand. Dom turned forward again and pressed back into his seat, holding onto the seatbelt.

‘There, see it?’

Andy didn’t reply. He was concentrating. He slammed on the brakes, and the BMW hit their rear end, shoving them forward. Tyres screamed. The BMW fell back a little, and Andy flipped the steering wheel to the right.

The Focus’s nose drifted perfectly into the narrow lane’s mouth, and Andy immediately dropped two gears and floored it. Unable to make the turn, the BMW slammed into the raised bank behind them, missing them by inches. As they powered away, Dom saw steam burst from the silver car’s front end, its wing crumpled, windscreen hazed.

They soon rounded a bend and the pursuing car was lost from sight.

Andy let out a held breath, gasping a few times. ‘Result,’ he whispered. ‘You okay?’

Dom could not speak. He turned away, watching the hedgerows passing by. With a sick feeling in his stomach he realised that he’d have to go straight to Monmouth now, to work, chatting with Davey and talking about how best to get these wires here, those there, lifting floorboards and drinking tea and eating biscuits.

‘My car’s bumped,’ he said.

‘We’ll sort that. Leave it to me. You okay, Dom?’

‘Yeah. No. Who were they?’

‘Looney Tunes.’ Andy laughed. Dom joined in, high and hysterical and sounding like someone he didn’t know.

Chapter Six

Pillbox

For a moment everything was as it should have been.

Dom surfaced from dreams and dragged some of them with him, balancing them momentarily with reality. Awareness started to build – who he was, where he lived, everything that made him Dominic. The dreams withered and receded. He groaned and stretched, eyes still closed, joints clicking to remind him of his age.

Then he remembered the day before and wished he could fall back asleep. He groaned again, this one more like a deep sigh. What have I done?

Daisy screamed.

Dom sprang upright, sitting in bed swaying and dizzied.

‘It wakes!’ Emma said beside him.

‘Daisy!’ He threw the duvet off and sat on the edge of the bed. Everything felt wrong. Music pulsed from Daisy’s room, when he rubbed sleep from his eyes he saw Roadrunner with a human body, and downstairs their dog, Jazz, was whining.

‘Ease up, action man. She’s only singing.’

He glanced back at Emma. She was sitting back against her propped pillows, phone in hand, hair sleep-tousled, corner of her mouth raised in amusement. Daisy’s voice rose again, and Dom slumped back into his pillow.

‘You call that singing?’

‘She’s got Muse’s new album. Trying to match that singer’s warble.’

‘He does not warble,’ Dom said, feigning hurt. It was a conversation they’d had many times before. He welcomed its familiarity.

‘Like a dog with its bollocks trapped in a gate.’ She muttered this, swiping something on her phone and attention already elsewhere.

‘He’s a rock god,’ Dom said. ‘Classically trained. Not my fault you have no taste in music, and your daughter has.’

From Daisy’s room the track ended and she fell silent. Jazz continued whining from the kitchen below them, eager to see them all. They were familiar morning sounds that made Dom feel almost comfortable.

Sunlight cast across him through a chink in the curtains, and when he relaxed back onto the bed and closed his eyes he saw that white van and silver BMW, cartoon characters hefting guns.

‘Feeling better this morning?’ Emma asked.

‘Yeah, think so.’ He answered without opening his eyes, scared that she’d see straight through him. She usually did. He’d told her he had a bad headache the previous evening, needing something to cover up the way he was acting. Weird, twitchy, unsettled. He’d even cancelled his usual Monday evening squash match with Andy, much to his friend’s disapproval. We need to be normal! Andy had said to him down the phone. I just feel a bit rough, he’d replied, unable to say more because Emma had been sitting on the other end of the sofa.

They’d stuck to their plan. After driving back from Upper Mill to Usk they headed into the hills just before the small town, parking off a barely used lane. Dom had left a shovel there the day before on his way home from work. Distant sirens, source unseen, had been the only sign of police.

The old pillbox was almost subsumed by ivy and brambles, hidden in a small woodland that had likely not even been there during the war. They pushed their way inside, careful to disturb as little of the undergrowth as possible. The shadowy interior stank musty and old, as if the war years had hung around. A pile of rusted drinks cans in one corner, the body of a mattress almost completely rotted into the ground, a black bag burst and spilling decayed cloth insides, all paid testament to its last occupant from some time ago. There were no signs of recent use.

Andy had used his phone as a torch while Dom dug. Then they swapped over. It only took half an hour. As Andy dumped the heavy post bag into the hole, Dom realised that they hadn’t even checked how much was there. They shoved the soil back over and patted it down, kicking the remaining turned soil into the corners. Dom used the shovel to drag the black bag across the floor. It came apart and spilled shreds of old clothing, and the stink as he dumped it on the covered hole made him gag. Things crawled away in the darkness, rustling dried leaves. He wanted to get out of there.

He’d dropped Andy at a bus stop and then headed to Monmouth. He was only an hour late for work, and he told Davey that he’d swung by the merchant’s to pick up some new tools. He had them ready in the car boot.

Their clients had made him a mug of tea and brought a plate of biscuits, and he and Davey had sat and chatted about things he could no longer remember. Then he’d worked. Then he’d come home. Dinner with Emma and Daisy, driving Daisy to her usual evening scout meeting, watching an episode of Breaking Bad with Emma instead of his usual Monday squash match. A hug in bed and then, after a long time, some troubled sleep.

And today was the first day of the rest of his life.

‘I’ll get the car looked at today,’ he said.

‘Should have called the police,’ Emma mumbled, still distracted by her phone.

‘It was a bump in a car park. Last thing they’re interested in.’ He’d been pleased to discover that damage to his car was minimal. The rear bumper had absorbed the force of the shunt, and where the van had touched them there was a scrape in the paintwork, nothing more. The wing mirror displayed no signs of any impact. It could have been so much worse.

‘Still. Ignorant bastard, whoever did it.’

Dom opened his eyes and stared at the ceiling, because with them closed he saw Roadrunner’s leering face.

‘Bloody hell,’ Emma said. He felt her stiffen in bed beside him. From across the landing Muse started again, the same song, Daisy’s enthusiastic but imperfect voice singing along. ‘Did you see this?’ Emma asked.

‘See what?’

‘Upper Mill post office.’

Dom’s blood ran cold. But of course it would be news. Locally, at least, if not nationally.

‘What about it?’

‘It was robbed yesterday morning. Whoever did it killed the postmistress and her granddaughter. How horrible. God, it’s only thirty miles from here.’

‘Killed them?’ Dom sat up again, but this time it was much harder than before. Everything felt slow, his body heavy, an ice-cold shock around his heart giving way to hot lead running through his veins. Sweat prickled his brow.

‘Yeah. Awful. Hope they catch the bastards.’

Dom couldn’t stop blinking. His eyes stung, and perhaps between blinks he could reset things, put things right. He already knew that they’d crossed a line. Now, that line had been painted blood-red.

‘Dom? Babe?’ He felt Emma’s hand on his arm and he leaned into her, kissing her cheek before standing from the bed.

‘Bladder’s going to explode.’

‘Dom, what is it?’

He stood at their open door, looking out across the landing at Daisy’s closed bedroom door. He’d heard the postmistress’s granddaughter singing. She’d sounded happy, carefree, like young kids should.

‘I’m okay. Just a shock, that’s all. Andy and I sat across the square from that place a few days ago.’ He remembered the laughing woman. ‘Might even have seen the post office owner.’ He looked back at his wife, terrified that the truth of things would be painted across his expression, in his eyes.

‘Yeah, it’s horrible,’ Emma said. She was scanning her phone again, scrolling slowly through the rest of the day’s news, already moving on.

And what will she see? he wondered.

The Hulk and Iron Man made off in a red Ford Focus just as their accomplices arrived, and soon after that the gunshots were heard.

The white van hit the red car.

It’s possible that two separate gangs were involved.

The Hulk and Iron Man were carrying weapons hidden in carrier bags.

‘We didn’t have weapons,’ he whispered as he stood in their bathroom trying to piss. His bladder wouldn’t let go. It was as if someone was standing behind him staring intently at the back of his neck, and he even glanced back over his shoulder.

‘Daisy, turn that down!’ Emma shouted. Daisy had turned up her iPod dock. Muse were rocking out.

Dom sobbed, once, and turned it into a cough.

‘Put the kettle on, babe,’ Emma called.

‘Yeah.’ He started to piss, but still felt eyes on him. That poor woman. Her poor grandkid.

He needed to speak to Andy.

‘Of course I’ve seen the news.’

‘We need to go to the police.’

‘And tell them what?’

‘What we saw.’

Andy didn’t reply for a few seconds. Dom could hear him breathing lightly, slowly, sounding in control. ‘Really, Dom?’

‘I dunno. It’s just … they shot them, Andy.’

‘You haven’t actually read the news, then.’

‘No. Emma told me. Why?’

‘They made the kid watch while they smashed the woman’s skull with something heavy. Then they glued the girl’s nostrils and lips shut with superglue.’

Dom felt the world spinning, or he was spiralling while everything else was motionless. He felt sick. ‘Jesus fucking Christ.’

‘So you really want to go to the police, and tell them we robbed the post office then saw these other bad guys appear to finish them off?’

‘We didn’t kill them.’

‘I know that, Dom! But we’re the bad guys too.’

‘Not that bad.’

‘They’d never believe there wasn’t a link! We admit it, they don’t find the others, we’re guilty of murder.’

‘No,’ Dom said. ‘Nobody gets hurt. That’s what we said.’

‘Yeah, I know, mate.’

‘That poor girl.’

Andy sighed. The phone line crackled. ‘Hardly bears thinking about,’ Andy said. Dom stared through his windscreen across the car park. There weren’t many cars here this early in the morning, and soon he’d go to the local shop to buy his lunch for the day. But he was suddenly all too aware of the damage to his car’s rear wing. It was superficial, little more than a few scratches. He’d already cleaned the mud from his number plates and disposed of the brightly coloured window blinds. But even though he could see no one else around, he felt eyes on him, sizing up the car and taking notes, ready to connect it to the robbery.

And then the white van hit the red car, Officer, and I’ve just seen it in Usk, I even know the guy who drives it, he’s an electrician and a governor at his daughter’s school and I’d have never expected that of him, not robbery, and definitely not murder.

He always seemed so quiet.

Such a nice family.

Nothing like that happens here.

‘Got to get my car done,’ Dom said. ‘I don’t believe we were stupid enough to use it.’

‘It wasn’t stupid. We weren’t stupid. It was just bad luck.’

‘Bad luck that’ll get us—’

‘I know a guy who’ll do the car, up in Shropshire. I’ve already spoken to him, there and back in a day.’

‘I can’t drive to Shropshire, I have to work!’

‘Which is why I’ll do it.’

Dom frowned, thinking things through. His mind was a fog. He couldn’t get anything straight, and if he tried to concentrate on one problem, all the others started battering at the edges of his consciousness.

‘I just can’t think straight,’ he said.

‘You don’t need to. That’s why I’m here. Get to work, go home tonight and hug Daisy. Have some wine, shag your missus. Everything’s going to be fine.’

‘Andy. Do you think if we hadn’t done it, those others might have left them alive?’

Andy sighed heavily, and fell silent for so long that Dom thought the line had been cut.

‘Andy?’

‘That wasn’t just murder. They enjoyed what they did to that girl. So I doubt it. No, they wouldn’t have been left alive. We had no influence over what happened to them. Understand?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Sure?’

‘Yeah. Andy? What if they come looking for us?’

‘They’ll be long gone by now.’

‘How do you know?’ Dom asked.

‘Because I would be. Now what time can you get here?’

Chapter Seven

A Quiet Life

She was Jane Smith, the do-over woman, and upon waking every morning her new life built itself from scratch.

She relished those briefest of moments between sleep and full consciousness, when all she knew was the lonely warmth of the French gîte’s bedroom, the landscape of bare grey stone walls, the roof light affording a view of the clearest blue sky, and the scents of summer drifting through windows left open all night. For that shortest of times she was free and carefree.

But reality always rushed in, as if she would suffocate and die without it. Her life was constructed around her and she pulled it on like a costume. Her name, her history, why she was here and where she had been before. It no longer needed learning and repeating, this new existence, because she knew it so well. She was experienced at living a lie.

Fragments of her old, real life always hung around, like stains from the past. But she did her best to restrict them to dreams, and nightmares.

She stretched beneath the single sheet. Her body was thin, lithe and strong, limbs corded with muscles. She enjoyed the feeling of being fit. There were hurdles to fitness, buffers against which she shoved again and again, but she enjoyed fighting them. She knew that the more years went by, the harder it would be to deny the wounds and injuries. But for now they acted as badges of honour. Scars formed a map of her past, a constant reminder of her old life that made-up names and histories could not erase.

A spider was crawling high across the stone gable wall close to the sloping ceiling. It was big, body the size of her thumbnail, legs an inch long. She’d seen it before, usually on the mornings when she woke earlier than normal. It probably patrolled her room at night, secretive and silent and known only to her. She imagined it exploring familiar ground in search of prey, and perhaps it sometimes crawled across her skin, pausing on her pillow to sense her breath, her dreams.

It scurried, paused, scurried again, eventually disappearing into its hole until the sun went down. She liked the idea of it spending daylight out of sight. Its sole purpose was existence and survival. There was something pure about that.

She sat on the edge of the bed, stretched again, then walked naked down the curving timber staircase and into the bathroom.

She’d been living in the gîte in Brittany for a little over three months, and she knew its nooks and crannies probably better than the French owners.

In a slit in the bed mattress was a Glock 17 pistol. Tucked behind a stone in the stairwell wall was a Leatherneck knife. A loose floorboard in the bathroom hid a sawn-off shotgun and an M67 grenade, and downstairs on the ground floor, beneath a flagstone in the kitchen, was a small weapons cache containing another pistol, a combat shotgun, and several more grenades.

Though aware of everything around her, Jane Smith did not think of these things now. Her life was as quiet and peaceful as she had ever believed possible. But none of this made her feel safe.

There was no such thing as safe.

She used the toilet, then went down the second flight of stairs to the kitchen. Kettle on, coffee ground, she watched from the kitchen window as the new day was birthed from the dregs of night.

Leaving the coffee to brew, she opened the wide glazed doors that led onto the gravelled terrace. Several rabbits sat across the lawned area beyond. One of them pricked up its ears and froze, but it did not run. Birds sang and swooped across the lawn, picking off flies flitting in the soft morning mist.

The sun would burn the mist away very soon, but for now it formed a pale haze across the landscape. The large lawned garden that sloped down to the woodland, the fields beyond, and past them the wide lake and the steadily rolling hills, were all silent but for the sounds of nature. She did nothing to disturb the peace.

Still, she would not step from the door without dressing. The chance of anyone watching was small. But if a local had walked through the woods this early, and had strayed from the public paths to the edge of the gîte’s large property, she did not want to draw undue attention to herself. The quiet Englishwoman could have been anyone. The naked Englishwoman would draw second glances, and discussion in the village bar-tabac, and a form of notoriety.

Jane Smith was well versed in keeping herself unnoticed.

She took her coffee upstairs, showered and dressed. Then she locked the house and cycled her old bike up to the small village of Brusvily. The patisserie was already open, and she smiled and exchanged a few words with the owner in her broken French. She was getting better, and she knew that the locals appreciated her efforts. They were used to British holidaymakers assuming that everyone spoke English, and she made a point of only conversing in French when she was away from the gîte. Just another way to try and fit in.

She bought croissants for breakfast, and bread rolls, ham and cheese for lunch. That afternoon she planned a run down through the woods to the lake, a long swim in its cool waters, then a hike along its shore to the nearest town. She’d eat dinner there, then perhaps run back the same way, depending on how stiff her hip was. If it was giving her grief, she’d walk.

Back at the gîte she brewed more coffee and sat beneath the pergola on the terrace, eating the croissants with strawberry preserve, drawing in the sights and sounds of summer. This had been a long, hot one, and the lawns were scorched dry by the sun and lack of rain.

Her son, Alex, comes crying to her with a grazed knee, grass stains surrounding the scratches.

Jane Smith paused only for a moment, last chunk of croissant halfway to her mouth. Her coffee steamed. A breeze sang through the corn crops in the neighbouring field and stirred the wild poppies speckling its edges like beads of blood on an abraded land.

She finished eating her breakfast and drinking her coffee, licking her fingers and picking up pastry crumbs from the plate. The memory was already gone. But every such memory was also always there.

This life was a thin veneer. Routine gave it substance, and repetition made it almost like being free.

But Jane Smith was more than one person. After brewing her third cup of strong coffee of the day, and still before nine in the morning, she picked up her iPad.

First she accessed Twitter. Her current account was under one of many pseudonyms, but it was time to change, so she opened a new account under a new name. A few quick posts about apple pie recipes, pictures of cakes, and a couple of funny cat memes, then she searched some cookery hashtags and friended a handful of random people. That done, she accessed five accounts that she liked to keep track of and friended those, too. These people were in her past, and though she’d made a promise to the few she liked, most would never want to see her again. She might have helped them, but in many cases she had corrupted and cursed them, too. Salvation came at a price.

She knew that more than most.

There were no messages there for her, secretive or otherwise, and nothing to raise her concern. She was glad.

She was always glad.

Leaving Twitter running in the background, she surfed other social media sites from a variety of fake ISP accounts. No name was her own, and none were those she had used in real life. Her net activity left no trail, and every relevant page or search was bookended with several random surfs.

Everything was quiet. That was how she liked it. She could have lived like this for the rest of her life, if her sense of morality allowed. It wasn’t that she was always out for vengeance. She wasn’t sure what it was.

It’s all I can do, she’d think when she mused on things. And considering what she had been, and who she’d had, that was the most depressing thing of all.

When she started scrolling through the news sites and saw the item, and scanned the first paragraph, everything changed. Her stomach dropped, and she felt the familiar sense of change settling around her.

The calm reality of her life at the gîte became a facade. Ever since becoming the person she now was, she’d had the sense of the world beyond her horizons conspiring to draw her out and cut her down.

There were plans, conspiracies, machinations, and sometimes she even imagined vast machines working secretly beyond the hills and past the curvature of the Earth, great steam-driven things that drilled and burrowed through the hollows she could not see, the places she did not yet know. They would connect like massive spider webs, drawing tighter and closer until there she was. Caught. Trapped by circumstance, and unable to look away.

All the horrors she had witnessed and experienced, and the terrors she had perpetuated herself, made looking away impossible.

‘Now here we are,’ she said. She read the whole article, picked up the phone, dialled. After four rings she disconnected, then she dialled again. He picked up after three. That way they both knew that things were well.

But not for long.

‘Have you seen the news?’ she asked.

‘I try to avoid it. Too depressing.’

‘There was a double murder in South Wales. A girl had her lips and nostrils glued shut.’

Silence from the other end.

‘Post office job gone wrong.’

‘So?’

She frowned. It was strange having this conversation in such calm, beautiful surroundings. Over the hills, she thought. Past the trees. Machines turning and steaming, vast cogs grinding, dripping oil, casting lines to hook into my flesh.