Полная версия:

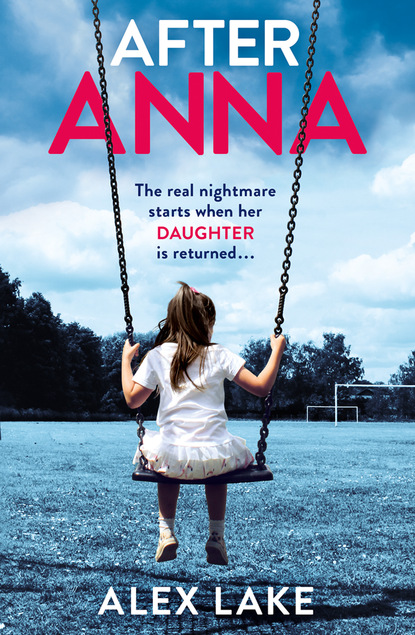

After Anna

‘I thought that was what you said,’ Karen murmured. ‘Mrs Crowne, I think there’s been a mix-up.’

A mix-up. Not words you wanted to hear in connection with your five-year-old daughter.

Julia stopped. She stared at the cast iron school gates. Both were adorned with the school crest: an owl clutching a scroll above the letters ‘WS’.

‘What do you mean?’ she said, her voice tightening with the beginnings of worry. ‘What kind of mix-up?’

‘Anna’s not here,’ Karen said, her tone retreating into something official, something protected. ‘We thought she’d left with you.’

iii.

Julia broke the connection. She ran through the gates to the school entrance and pushed open the worn green door, then ran along the corridor in the direction of the administrative offices. Karen, the school secretary, tall and thin, with a head of tight black curls, was standing outside the office door, her face drained of colour.

‘Mrs Crowne,’ she said. ‘I’m sure everything’s ok. Perhaps your husband picked her up.’

The twitchy, alert look in her eyes belied the calm reassurance of her tone. Julia’s stomach fluttered, then contracted. She had a sudden, violent urge to vomit.

‘I’ll check,’ she said. She dialled Brian’s number.

‘Hello.’ His voice was hard; his dislike of her deliberate and obvious. ‘What do you want?’

Julia licked her lips. They were very dry. ‘Brian,’ she said. ‘Is Anna with you?’

‘Of course not. I’m at school. It’s your day to pick her up.’

‘I know,’ Julia paused, ‘but she’s not here.’

There was a long silence.

‘What do you mean she’s not there?’ The hardness in his voice had softened into concern. ‘Where is she?’

‘I don’t know,’ Julia said, wanting, even in this situation, to add a sarcastic obviously. ‘Maybe your mum picked her up?’ She almost smiled with relief. This was the answer, after all, of course it was. Edna, her grandmother, had come on the wrong day. The relaxation was almost palpable, like the glow from a stiff drink.

‘It wasn’t mum,’ Brian said. ‘She’s at home. She called an hour or so ago to ask about something. She wanted to know where the stopcock for the mains was. Apparently, there was some kind of leak in the kitchen.’

The hopeful glow faded. Julia swallowed; her mouth powder dry. ‘Then I don’t know where she is.’

They were words you never wanted or expected to say to your husband or wife or anybody at all about your five-year-old daughter. Five-year-old children were supposed to have known whereabouts at all times: with one or the other parent, at school, at a friend’s house, with a select few relatives, who, in Anna’s case, were Brian’s mum Edna, or, occasionally, when they were back from Portland, Oregon, Brian’s brother Simon and his wife Laura, these being the extent of their relatively small family circle.

‘You don’t know where she is?’ Brian asked, his voice caught between anger and panic. ‘You’d better find her!’

‘I know.’

‘And it’s nearly half past three! How come you’re just calling now?’

‘I was a bit late,’ Julia said. ‘I just got here. I thought the school would be – I thought she’d be here.’

‘Did you let them know you’d be late?’

‘No, I … my phone was dead. I just assumed … ’, her voice tailed off.

‘Jesus,’ Brian said. ‘She could be anywhere. In thirty minutes, she could be anywhere. She could have wandered … ’ he paused. ‘I’ll be there as soon as I can. Start looking for her. Search the grounds and the streets nearby.’

‘OK.’ She felt frozen, unable to think. ‘We’ll search for her.’ She looked again at Karen, who nodded.

‘I’ll tell the cleaning staff to help,’ Karen said. ‘And Julia – don’t worry. She’ll turn up, I’m sure. She’s probably in someone’s garden, or the newsagent, or somewhere like that.’

Julia nodded, but the words were not at all reassuring. They were little more than meaningless sounds.

‘Brian,’ she said. ‘I have to go. I have to get started.’

‘One more thing,’ Brian said. ‘Call the police.’ He hesitated. ‘In fact, I’ll call them. You start looking for her. Start looking for Anna.’

The line went dead. Julia’s hand dropped to her side. Her phone, loosely gripped between her thumb and forefinger, dropped to the floor.

Oh, God,’ she said. ‘Oh, God.’

2

The First Hours

i.

These were the crucial hours.

If you had been seen then the police would learn about that soon enough. First, they would check the immediate area, then they would drive the route to the girl’s house to see if she had set off for home alone. When they didn’t find her they would contact all the parents and staff who had been there at three p.m. and ask them what they had seen. Then they would interview the family. They always looked close to home first, not that they would find anything.

And, of course, they would check the school’s CCTV. You knew you weren’t on that. All they would see was the girl walking out of shot and into oblivion.

Of course, there was always the possibility that there was a camera in the area you hadn’t spotted. You’d checked carefully, but it was possible.

And if there was, or if they had seen you, and realized who you were, then the police would be here soon enough, knocking on your door.

But that was OK. You had a plan for that. For these first hours the girl was elsewhere, stashed in your neighbour’s garage; your neighbour who was in Alicante for the fortnight, and who had left you their house keys because you’re our only neighbour so you can keep an eye on the place in case anything happens.

Something had happened, but not something they could have imagined.

You’d backed into their garage and unloaded her, then put your car away. No one would have seen. There was no one to see. No prying eyes. No spying eyes. It gave you comfort that you were invisible to the world, allowed you to get on with your life unobserved. Not just now, with the girl, but the other times as well.

And now the girl lay there, sleeping on the floor of a large doll’s house that the father had built for his kids, his braying, noisy kids, who had outgrown it. It was just big enough for her to lie full length in, her feet by a small table, her head on a bag of sand, which was destined to re-fill the sand pit that the two spoilt kids who loved to disturb your afternoon peace played in.

She could stay there until midnight. That was when you would bring her inside and introduce her to her new home.

Her temporary new home.

She wouldn’t be here for too long.

ii.

Julia ran out of the green front door of the school. Ahead of her were the gates, still open from when she had come in. They were supposed to be kept locked at all times. Supposed to be. The problem was that things that were supposed to be often weren’t. She was supposed to have been there to pick up her daughter, but that didn’t help much now.

She pictured the school at the end of the day. Kids in uniforms pouring out of the school doors, the younger ones heading straight for the parents outside the gates, the older ones running into the playground for a last few minutes of fun before home and dinner and bedtime, the teachers hanging back, making sure that everything went as it should, which it would, because it always did. Every child would be accounted for, either picked up by whoever was supposed to be there for them or held back inside the sanctuary of the school because their adult was late. No one slipped through the cracks, not at this small, fee-paying private school. The parents here could be relied on to make sure that their children were properly looked after, that they were not left waiting and vulnerable. The chance of a mistake was vanishingly small.

But it was not impossible.

Julia pictured a small, dark-haired girl with a pink Dora the Explorer backpack and new black leather shoes walking out of the gate with the other pupils and looking around for her mother, frowning when she didn’t see her. And then maybe walking a little further down the street, perhaps thinking that she could find the familiar black Volkswagen Golf her mum drove. And then, a hand tapping her on the shoulder, a large, man’s hand, with thick fingers and black hair sprouting from the point where the hand met the wrist – Julia blinked the vision away. She had to stay calm, or at least calm enough to look for her daughter.

‘She’s fine’, she said, talking to herself. ‘She’s fine. She’s just waiting somewhere.’

The words didn’t make her feel any better. There was a ball of fear and panic knotted somewhere between her stomach and her sternum so big and real and hard that it was making it difficult to draw breath and to keep her head from dizzying.

But she had to act. She had to do something. And the quicker the better. She ran towards the iron gates. She would start outside the school. If Anna was in the building or the school grounds then she was probably OK. She could wait to be found. If she was outside – well, she needed to be found as soon as possible. Outside were cars and dogs and buses and people who might have an interest in an unaccompanied five-year-old girl that they shouldn’t have.

‘Anna!’ she shouted. ‘Anna! Where are you?’

She heard a similar call from inside the school, as Karen started her search.

‘Anna!’ Julia shouted. ‘It’s Mummy! Where are you, darling?’

She exited the gate and faced her first decision. Left or right? Left, towards the village centre, or right, towards a small development of overpriced cookie-cutter commuter boxes surrounded by scrubby fields? Boxes with closed doors and sheds and hiding places, boxes that were unoccupied and unobserved during the day when the inhabitants were at work or at school, boxes into which a girl could be smuggled. So, left or right? It was normally such a small decision. If you got it wrong you could backtrack and try again. But this time it felt bigger, more important. This time it was not just left or right: it was towards Anna or away from her.

But do something, Julia thought. Standing still is the worst option.

She went left, towards the village. It was more likely Anna had wandered that way, gone towards people and the newsagents and the recently opened old-fashioned sweet shop that sold sweets in quarter pounds and half pounds from jars behind the counter. The Village Sweete Shoppe, it was called, and Anna loved it.

The narrow, tree-lined road to the village curved left then descended a small gradient. The houses along the road were old and large and concealed behind high sandstone walls and thick foliage, which was both a good and a bad thing: it was unlikely that Anna would have been able to get into the gardens, but if, for some reason she was in there, she would be impossible to see.

These were the thoughts Julia had now. She saw once innocent gardens as threats to her daughter. The whole world was twisted into a sick new configuration. It made her head spin.

‘Anna!’ Julia was surprised at how loud her voice could go. She hadn’t used it like that for years. Even when she and Brian were in full flow she didn’t turn it up this much. ‘Anna! It’s Mummy! If you can hear me, just say something. I’ll come and get you!’

There was no reply. Just the distant barking of a dog (is it barking at Anna? Julia wondered) and the noise of a car engine (where’s that car going? she thought. Who’s in it?) and somewhere, incongruously, a pop song being played at loud volume.

She ran down the hill, her heels clicking on the pavement. ‘Anna!’ she shouted. ‘Anna!’

There was a rustle in a thick rhododendron bush to her left. Julia stopped and pulled back the branches. The inside was cool and smelled of wet earth.

‘Anna?’ she said. ‘Is that you?’

There was another rustle, deeper in the bush. Julia pushed her way in; her heart thudding.

‘Anna’ she called. ‘Anna!’

The rustle came again, then a blackbird emerged from the other side of the bush. It looked at Julia, then took flight and vanished into the branches of a sycamore tree.

Julia stood up. To her left was a driveway leading to a covered porch. A man in his sixties, with grey hair and walking cane, was standing in the doorway, looking at her.

‘Everything OK?’ he asked. ‘I heard you shouting.’

‘It’s my daughter,’ Julia said. ‘I can’t find her.’

The man frowned. ‘Oh dear,’ he said. ‘What does she look like?’

‘She’s five. Dark hair. She has a pink rucksack and she’s in uniform.’

‘Is she at the school? Westwood?’

Julia nodded. ‘Have you seen her?’

‘No. But I could help you look?’ He lifted his walking stick. ‘I’m not very mobile, but I could drive around and look for her.’

Julia looked at him, suspicion clouding her mind. Did he have Anna? Was this some double bluff? She caught herself; he was just someone trying to help, and she needed all the help she could get at the moment. Probably, anyway. She’d mention him to the police later, if it came to that.

‘That would be wonderful,’ Julia said. ‘Maybe I should drive, too.’

‘You can probably look more closely on foot. I’ll take my car, though. And my wife is home. She’ll take the other car. What’s her name, if we do see her?’

‘Anna. Just stay with her and call the police.’

‘OK,’ the man said. ‘Good luck.’

‘Thank you,’ Julia said. She pulled herself out from the bush, wincing, as a twig or thorn or branch scratched her bare calf, then carried on towards the village.

As she ran, she examined everything – every hedge, every fence, every parked car – but felt she was seeing nothing. She didn’t trust her eyes, didn’t trust that Anna might not appear where she had just looked, and so she found herself checking the same places two, three times before allowing herself to move on. Part of her knew it was unnecessary and irrational, but she couldn’t help it; the stakes were just too high, the consequences of missing her daughter – who must be somewhere nearby – were too awful for her to allow herself to make a mistake and miss what was – what might be – in front of her nose.

She’d heard that when the police searched for evidence, when they got one of those lines of people to sweep a field or moor or wasteland, they never let the people who were involved – that is, the people who were looking for their loved ones – join in. Apparently, if you were too close to whoever was lost your searching abilities were compromised in some important way. Perhaps it was that you wanted to find whatever it was too much to maintain the calm, patient detachment required.

Whether that was true or not, she certainly did not feel calm or patient. What she felt was panic, a panic that threatened to overwhelm her and leave her in a heap on the pavement. It took a monumental effort for her not to put her face in her hands, sink to her knees, and start to pray.

‘Oh my God,’ she muttered. ‘Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God.’ Then, for a moment, the panic rose and did take over and she stopped, her head craned forward, her gaze sweeping from left to right.

‘Anna!’ she screamed. ‘ANNA!’

She began to sprint. She had an image of Anna in The Village Sweete Shoppe, sitting on a stool by the window with a black liquorice stick staining her hand, her lips blackened with its juice. That was where her daughter was, she was sure of it. That was where Anna would have gone. There was nowhere else: Anna didn’t know anywhere else, really. At five, her world was the house and garden, school, the houses of some friends, and a few places that she visited with her parents. One of those was the sweet shop.

They went there sometimes after school. Julia didn’t give her daughter too many chocolates or crisps or ice cream or other junk food, but for some reason the stuff in The Village Sweete Shoppe felt different, more wholesome. It was the experience as much as anything: talking to the proprietor, weighing the various choices – pear drops, Everton mints, cola cubes – and counting out the price. It was old-fashioned, the way it had been when Julia was a child, when she had taken her pocket money on a Saturday morning and gone with her dad to the local newsagent and chosen the sweets she wanted, and she liked the thought that her childhood and her daughter’s shared something.

They went there, once or twice every month. They left the car parked outside the school gates, walked down the hill, and went to buy sweets. It was about the only thing they ever did straight after school, the only thing that Anna knew. And she loved it.

So she was there, Julia knew it and as she sprinted she knew she was going to get there and find her daughter and sweep her up into a protective embrace from which she thought she might not ever let her go.

The bell above the door jangled. Julia took a couple of quick steps into the shop, looking wildly from corner to corner.

‘Hello,’ the owner, a retired postal worker called Celia, said. ‘Can I help?’

‘Has my daughter been in?’ Julia asked.

The owner thought for a second, trying to place Julia. ‘Your daughter’s Anna, isn’t she? A dark-haired little girl? Likes chocolate mice?’

‘That’s her. Has she been in?’

The owner shook her head. ‘No,’ she said. ‘She’s a bit young to come in on her own.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘I’ve been here all afternoon. Hardly anyone has been in, and I’d remember her, especially if she was alone.’ Celia leaned forwards. ‘Is everything OK?’

Julia looked past the foot-long lollipops and chocolate rabbits to the street outside the shop window. Anna wasn’t here. She was somewhere out there.

Somewhere. Out. There.

Now the panic did take hold. She turned back to the Celia, her legs weakening.

‘I’ve lost her,’ she said. ‘I’ve lost my daughter.’

iii.

It happens to every parent, one time or another. Perhaps in a supermarket, perhaps in the library, perhaps in the back garden.

You look around and your child is not there.

‘Billy!’ you shout, then, a little louder. ‘Billy!’

And Billy replies, and comes toddling into view, holding a bag of flour, or a book, or with a worm in the grip of his pudgy hands. Or maybe he doesn’t, and you have that sudden lurch of fear, that tightness in the back, and loose feeling in your stomach, and you look around a little wildly, before running to the end of the aisle or to the kids’ books section or to the back gate, and there he is. Little Billy; safe and sound.

And you swear you’re going to make sure you don’t let them out of your sight again, not for a second, because a second is all it takes.

And a second is all it takes. In one second, a kid can step out from behind a parked car or be shoved into a van or even just walk round a corner and get lost enough that it takes you ten agonizing minutes to find them, which, although agonizing, is the best possible outcome. You find them sitting on a bench chatting to a kindly stranger or playing with some kids they met or just wandering about absorbed in all the things they are seeing on their own for the first time.

And then you really swear that you aren’t going to let them out of your sight again, because, in that ten minutes your mind races to the worst possible conclusions: they’ve fallen in the canal, they’ve been hit by a car, they’ve been abducted.

And that’s the one that bothers you the most. They’ve been taken. Picked off the street in a neglectful moment and taken. Gone forever. Alive or dead, it doesn’t matter. You won’t ever see them again, but you won’t ever be able to stop looking. And you won’t ever forgive yourself.

But, of course, even when you’re contemplating that horrific, tortured possibility, a still, calm voice at the back of your mind is telling you not to worry, that everything is ok, that it’ll all work out because it always does.

Except it doesn’t. Not always.

And you know that. Which is the most frightening thing of all.

Julia ran out of The Village Sweete Shoppe. She glanced left and right: the same choice again. Left into the village or right, back to the school. She turned left and jogged down the hill. If there was news at the school someone would phone her. At least this time her phone was charged.

A woman of her age, with short hair and an expensive-looking bag, was walking towards her. Without thinking, Julia caught her eye.

Julia, like many English women of her age and social class, had an aversion to both making a scene and bothering people that bordered on the pathological. She would no more have asked a stranger for help – to lend her money, perhaps, or let her use their mobile phone, or get assistance changing a car wheel – than she would have walked unannounced into their kitchen, opened their fridge, and made herself a salad.

This, though, was different. It was not a time to worry about social proprieties.

‘Excuse me,’ Julia said. ‘I’m looking for my daughter. She’s five, she has dark hair and a pink rucksack, and she’s in school uniform. Have you seen her?’

‘No,’ the woman replied. Her face took on an odd expression, a mixture of concern and sympathy that Julia found discomfiting. ‘Has she been missing long?’

‘Not that long. Twenty minutes. Maybe more.’

The expression deepened into a frown. ‘Gosh. That’s a long time.’

‘I know,’ Julia said. ‘Would you keep an eye out for her?’

‘Of course. I’ll help you.’ She gestured to the village car park. ‘I’ll look around the car park and check the library. There’s a playground round the back. She might be there.’

‘Thank you,’ Julia said. ‘Her name is Anna,’ she added. She set off down the slope. On the right was a pub; on the left a post office, although neither seemed the same as it had the last time she had seen them. Then they had been simple buildings, parts of the infrastructure of the village, communal places that offered warmth and light. Now they were threatening; places where Anna might be kept hidden.

She put her head around the post office door. There was a queue of four waiting for the one open booth.

‘Excuse me,’ she said, aware of her breathlessness. ‘I’m looking for someone. My daughter. Anna. Maybe you’ve seen her in the village?’

‘What’s she look like?’ a man in paint-splattered overalls asked.

Julia gave the description. It was already horribly familiar: dark hair, rucksack, school uniform. It fitted many five-year-old girls, but that didn’t matter, because there was one element that marked Anna out from all the others.

‘She’d have been alone,’ Julia said.

After a sympathetic pause – Julia was already starting to hate sympathetic pauses – followed shaking heads, murmured negatives: she hadn’t been in, and they hadn’t seen her.

Julia ran across the road to the Black Bear pub. It was dark inside, the windows grimy, the smell of smoke still lingering despite the ban on inside smoking. There were only three customers: an underage couple skulking in the corner and a man at the bar.

There was a woman tending the pumps. Julia walked over to her.

‘Excuse me,’ she said. ‘I’m looking for my daughter. She’s five.’

‘A bit young to be in here, love,’ the woman said. She was in her early fifties, Julia guessed, but looked older. She had heavily tattooed forearms and a lined face and was wearing a push-up bra.

‘I thought, maybe, she wandered in,’ Julia said. ‘I’ve lost her.’

The man at the bar looked up from his newspaper, his nose and cheeks red with broken capillaries.

‘Not seen her,’ he said. He patted the stool next to him. ‘I’ll buy you a drink, though, darling.’

The woman behind the bar – probably the landlady – shook her head in disapproval, but she didn’t say anything. She probably didn’t want to upset a regular. Couldn’t afford to. The pub was shabby; it didn’t look as if it was doing so well.