Полная версия:

Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories

‘I’ve heard of reconstructing a crime, of course,’ she said. ‘But I didn’t know you were so particular about details. But I’ll fetch the dress now.’

She left the room and returned almost immediately with a dainty wisp of white satin and green. Poirot took it from her and examined it, handing it back with a bow.

‘Merci, madame! I see you have had the misfortune to lose one of your green pompons, the one on the shoulder here.’

‘Yes, it got torn off at the ball. I picked it up and gave it to poor Lord Cronshaw to keep for me.’

‘That was after supper?’

‘Yes.’

‘Not long before the tragedy, perhaps?’

A faint look of alarm came into Mrs Davidson’s pale eyes, and she replied quickly: ‘Oh no – long before that. Quite soon after supper, in fact.’

‘I see. Well, that is all. I will not derange you further. Bonjour, madame.’

‘Well,’ I said as we emerged from the building, ‘that explains the mystery of the green pompon.’

‘I wonder.’

‘Why, what do you mean?’

‘You saw me examine the dress, Hastings?’

‘Yes?’

‘Eh bien, the pompon that was missing had not been wrenched off, as the lady said. On the contrary, it had been cut off, my friend, cut off with scissors. The threads were all quite even.’

‘Dear me!’ I exclaimed. ‘This becomes more and more involved.’

‘On the contrary,’ replied Poirot placidly, ‘it becomes more and more simple.’

‘Poirot,’ I cried, ‘one day I shall murder you! Your habit of finding everything perfectly simple is aggravating to the last degree!’

‘But when I explain, mon ami, is it not always perfectly simple?’

‘Yes; that is the annoying part of it! I feel then that I could have done it myself.’

‘And so you could, Hastings, so you could. If you would but take the trouble of arranging your ideas! Without method –’

‘Yes, yes,’ I said hastily, for I knew Poirot’s eloquence when started on his favourite theme only too well. ‘Tell me, what do we do next? Are you really going to reconstruct the crime?’

‘Hardly that. Shall we say that the drama is over, but that I propose to add a – harlequinade?’

The following Tuesday was fixed upon by Poirot as the day for this mysterious performance. The preparations greatly intrigued me. A white screen was erected at one side of the room, flanked by heavy curtains at either side. A man with some lighting apparatus arrived next, and finally a group of members of the theatrical profession, who disappeared into Poirot’s bedroom, which had been rigged up as a temporary dressing-room.

Shortly before eight, Japp arrived, in no very cheerful mood. I gathered that the official detective hardly approved of Poirot’s plan.

‘Bit melodramatic, like all his ideas. But there, it can do no harm, and as he says, it might save us a good bit of trouble. He’s been very smart over the case. I was on the same scent myself, of course –’ I felt instinctively that Japp was straining the truth here – ‘but there, I promised to let him play the thing out his own way. Ah! Here is the crowd.’

His Lordship arrived first, escorting Mrs Mallaby, whom I had not as yet seen. She was a pretty, dark-haired woman, and appeared perceptibly nervous. The Davidsons followed. Chris Davidson also I saw for the first time. He was handsome enough in a rather obvious style, tall and dark, with the easy grace of the actor.

Poirot had arranged seats for the party facing the screen. This was illuminated by a bright light. Poirot switched out the other lights so that the room was in darkness except for the screen. Poirot’s voice rose out of the gloom.

‘Messieurs, mesdames, a word of explanation. Six figures in turn will pass across the screen. They are familiar to you. Pierrot and his Pierrette; Punchinello the buffoon, and elegant Pulcinella; beautiful Columbine, lightly dancing, Harlequin, the sprite, invisible to man!’

With these words of introduction, the show began. In turn each figure that Poirot had mentioned bounded before the screen, stayed there a moment poised, and then vanished. The lights went up, and a sigh of relief went round. Everyone had been nervous, fearing they knew not what. It seemed to me that the proceedings had gone singularly flat. If the criminal was among us, and Poirot expected him to break down at the mere sight of a familiar figure the device had failed signally – as it was almost bound to do. Poirot, however, appeared not a whit discomposed. He stepped forward, beaming.

‘Now, messieurs and mesdames, will you be so good as to tell me, one at a time, what it is that we have just seen? Will you begin, milor’?’

The gentleman looked rather puzzled. ‘I’m afraid I don’t quite understand.’

‘Just tell me what we have been seeing.’

‘I – er – well, I should say we have seen six figures passing in front of a screen and dressed to represent the personages in the old Italian Comedy, or – er – ourselves the other night.’

‘Never mind the other night, milor’,’ broke in Poirot. ‘The first part of your speech was what I wanted. Madame, you agree with Milor’ Cronshaw?’

He had turned as he spoke to Mrs Mallaby.

‘I – er – yes, of course.’

‘You agree that you have seen six figures representing the Italian Comedy?’

‘Why, certainly.’

‘Monsieur Davidson? You too?’

‘Yes.’

‘Madame?’

‘Yes.’

‘Hastings? Japp? Yes? You are all in accord?’

He looked around upon us; his face grew rather pale, and his eyes were green as any cat’s.

‘And yet – you are all wrong! Your eyes have lied to you – as they lied to you on the night of the Victory Ball. To “see” things with your eyes, as they say, is not always to see the truth. One must see with the eyes of the mind; one must employ the little cells of grey! Know, then, that tonight and on the night of the Victory Ball, you saw not six figures but five! See!’

The lights went out again. A figure bounded in front of the screen – Pierrot!

‘Who is that?’ demanded Poirot. ‘Is it Pierrot?’

‘Yes,’ we all cried.

‘Look again!’

With a swift movement the man divested himself of his loose Pierrot garb. There in the limelight stood glittering Harlequin! At the same moment there was a cry and an overturned chair.

‘Curse you,’ snarled Davidson’s voice. ‘Curse you! How did you guess?’

Then came the clink of handcuffs and Japp’s calm official voice. ‘I arrest you, Christopher Davidson – charge of murdering Viscount Cronshaw – anything you say will be used in evidence against you.’

It was a quarter of an hour later. A recherché little supper had appeared; and Poirot, beaming all over his face, was dispensing hospitality and answering our eager questions.

‘It was all very simple. The circumstances in which the green pompon was found suggested at once that it had been torn from the costume of the murderer. I dismissed Pierrette from my mind (since it takes considerable strength to drive a table-knife home) and fixed upon Pierrot as the criminal. But Pierrot left the ball nearly two hours before the murder was committed. So he must either have returned to the ball later to kill Lord Cronshaw, or – eh bien, he must have killed him before he left! Was that impossible? Who had seen Lord Cronshaw after supper that evening? Only Mrs Davidson, whose statement, I suspected, was a deliberate fabrication uttered with the object of accounting for the missing pompon, which, of course, she cut from her own dress to replace the one missing on her husband’s costume. But then, Harlequin, who was seen in the box at one-thirty, must have been an impersonation. For a moment, earlier, I had considered the possibility of Mr Beltane being the guilty party. But with his elaborate costume, it was clearly impossible that he could have doubled the roles of Punchinello and Harlequin. On the other hand, to Davidson, a young man of about the same height as the murdered man and an actor by profession, the thing was simplicity itself.

‘But one thing worried me. Surely a doctor could not fail to perceive the difference between a man who had been dead two hours and one who had been dead ten minutes! Eh bien, the doctor did perceive it! But he was not taken to the body and asked, “How long has this man been dead?” On the contrary, he was informed that the man had been seen alive ten minutes ago, and so he merely commented at the inquest on the abnormal stiffening of the limbs for which he was quite unable to account!

‘All was now marching famously for my theory. Davidson had killed Lord Cronshaw immediately after supper, when, as you remember, he was seen to draw him back into the supper-room. Then he departed with Miss Courtenay, left her at the door of her flat (instead of going in and trying to pacify her as he affirmed) and returned post-haste to the Colossus – but as Harlequin, not Pierrot – a simple transformation effected by removing his outer costume.’

The uncle of the dead man leaned forward, his eyes perplexed.

‘But if so, he must have come to the ball prepared to kill his victim. What earthly motive could he have had? The motive, that’s what I can’t get.’

‘Ah! There we come to the second tragedy – that of Miss Courtenay. There was one simple point which everyone overlooked. Miss Courtenay died of cocaine poisoning – but her supply of the drug was in the enamel box which was found on Lord Cronshaw’s body. Where, then, did she obtain the dose which killed her? Only one person could have supplied her with it – Davidson. And that explains everything. It accounts for her friendship with the Davidsons and her demand that Davidson should escort her home. Lord Cronshaw, who was almost fanatically opposed to drug-taking, discovered that she was addicted to cocaine, and suspected that Davidson supplied her with it. Davidson doubtless denied this, but Lord Cronshaw determined to get the truth from Miss Courtenay at the ball. He could forgive the wretched girl, but he would certainly have no mercy on the man who made a living by trafficking in drugs. Exposure and ruin confronted Davidson. He went to the ball determined that Cronshaw’s silence must be obtained at any cost.’

‘Was Coco’s death an accident, then?’

‘I suspect that it was an accident cleverly engineered by Davidson. She was furiously angry with Cronshaw, first for his reproaches, and secondly for taking her cocaine from her. Davidson supplied her with more, and probably suggested her augmenting the dose as a defiance to “old Cronch”!’

‘One other thing,’ I said. ‘The recess and the curtain? How did you know about them?’

‘Why, mon ami, that was the most simple of all. Waiters had been in and out of that little room, so, obviously, the body could not have been lying where it was found on the floor. There must be some place in the room where it could be hidden. I deduced a curtain and a recess behind it. Davidson dragged the body there, and later, after drawing attention to himself in the box, he dragged it out again before finally leaving the Hall. It was one of his best moves. He is a clever fellow!’

But in Poirot’s green eyes I read unmistakably the unspoken remark: ‘But not quite so clever as Hercule Poirot!’

2

The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan

‘The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan’ was first published as ‘The Curious Disappearance of the Opalsen Pearls’ in The Sketch, 14 March 1923.‘Poirot,’ I said, ‘a change of air would do you good.’

‘You think so, mon ami?’

‘I am sure of it.’

‘Eh – eh?’ said my friend, smiling. ‘It is all arranged, then?’

‘You will come?’

‘Where do you propose to take me?’

‘Brighton. As a matter of fact, a friend of mine in the City put me on to a very good thing, and – well, I have money to burn, as the saying goes. I think a weekend at the Grand Metropolitan would do us all the good in the world.’

‘Thank you, I accept most gratefully. You have the good heart to think of an old man. And the good heart, it is in the end worth all the little grey cells. Yes, yes, I who speak to you am in danger of forgetting that sometimes.’

I did not relish the implication. I fancy that Poirot is sometimes a little inclined to underestimate my mental capacities. But his pleasure was so evident that I put my slight annoyance aside.

‘Then, that’s all right,’ I said hastily.

Saturday evening saw us dining at the Grand Metropolitan in the midst of a gay throng. All the world and his wife seemed to be at Brighton. The dresses were marvellous, and the jewels – worn sometimes with more love of display than good taste – were something magnificent.

‘Hein, it is a good sight, this!’ murmured Poirot. ‘This is the home of the Profiteer, is it not so, Hastings?’

‘Supposed to be,’ I replied. ‘But we’ll hope they aren’t all tarred with the Profiteering brush.’

Poirot gazed round him placidly.

‘The sight of so many jewels makes me wish I had turned my brains to crime, instead of to its detection. What a magnificent opportunity for some thief of distinction! Regard, Hastings, that stout woman by the pillar. She is, as you would say, plastered with gems.’

I followed his eyes.

‘Why,’ I exclaimed, ‘it’s Mrs Opalsen.’

‘You know her?’

‘Slightly. Her husband is a rich stockbroker who made a fortune in the recent oil boom.’

After dinner we ran across the Opalsens in the lounge, and I introduced Poirot to them. We chatted for a few minutes, and ended by having our coffee together.

Poirot said a few words in praise of some of the costlier gems displayed on the lady’s ample bosom, and she brightened up at once.

‘It’s a perfect hobby of mine, Mr Poirot. I just love jewellery. Ed knows my weakness, and every time things go well he brings me something new. You are interested in precious stones?’

‘I have had a good deal to do with them one time and another, madame. My profession has brought me into contact with some of the most famous jewels in the world.’

He went on to narrate, with discreet pseudonyms, the story of the historic jewels of a reigning house, and Mrs Opalsen listened with bated breath.

‘There now,’ she exclaimed, as he ended. ‘If it isn’t just like a play! You know, I’ve got some pearls of my own that have a history attached to them. I believe it’s supposed to be one of the finest necklaces in the world – the pearls are so beautifully matched and so perfect in colour. I declare I really must run up and get it!’

‘Oh, madame,’ protested Poirot, ‘you are too amiable. Pray do not derange yourself!’

‘Oh, but I’d like to show it to you.’

The buxom dame waddled across to the lift briskly enough. Her husband, who had been talking to me, looked at Poirot inquiringly.

‘Madame your wife is so amiable as to insist on showing me her pearl necklace,’ explained the latter.

‘Oh, the pearls!’ Opalsen smiled in a satisfied fashion. ‘Well, they are worth seeing. Cost a pretty penny too! Still, the money’s there all right; I could get what I paid for them any day – perhaps more. May have to, too, if things go on as they are now. Money’s confoundedly tight in the City. All this infernal EPD.’ He rambled on, launching into technicalities where I could not follow him.

He was interrupted by a small page-boy who approached him and murmured something in his ear.

‘Eh – what? I’ll come at once. Not taken ill, is she? Excuse me, gentlemen.’

He left us abruptly. Poirot leaned back and lit one of his tiny Russian cigarettes. Then, carefully and meticulously, he arranged the empty coffee-cups in a neat row, and beamed happily on the result.

The minutes passed. The Opalsens did not return.

‘Curious,’ I remarked, at length. ‘I wonder when they will come back.’

Poirot watched the ascending spirals of smoke, and then said thoughtfully:

‘They will not come back.’

‘Why?’

‘Because, my friend, something has happened.’

‘What sort of thing? How do you know?’ I asked curiously.

Poirot smiled.

‘A few minutes ago the manager came hurriedly out of his office and ran upstairs. He was much agitated. The liftboy is deep in talk with one of the pages. The lift-bell has rung three times, but he heeds it not. Thirdly, even the waiters are distrait; and to make a waiter distrait –’ Poirot shook his head with an air of finality. ‘The affair must indeed be of the first magnitude. Ah, it is as I thought! Here come the police.’

Two men had just entered the hotel – one in uniform, the other in plain clothes. They spoke to a page, and were immediately ushered upstairs. A few minutes later, the same boy descended and came up to where we were sitting.

‘Mr Opalsen’s compliments, and would you step upstairs?’

Poirot sprang nimbly to his feet. One would have said that he awaited the summons. I followed with no less alacrity.

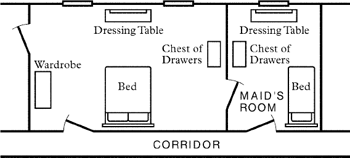

The Opalsens’ apartments were situated on the first floor. After knocking on the door, the page-boy retired, and we answered the summons. ‘Come in!’ A strange scene met our eyes. The room was Mrs Opalsen’s bedroom, and in the centre of it, lying back in an armchair, was the lady herself, weeping violently. She presented an extraordinary spectacle, with the tears making great furrows in the powder with which her complexion was liberally coated. Mr Opalsen was striding up and down angrily. The two police officials stood in the middle of the room, one with a notebook in hand. An hotel chambermaid, looking frightened to death, stood by the fireplace; and on the other side of the room a Frenchwoman, obviously Mrs Opalsen’s maid, was weeping and wringing her hands, with an intensity of grief that rivalled that of her mistress.

Into this pandemonium stepped Poirot, neat and smiling. Immediately, with an energy surprising in one of her bulk Mrs Opalsen sprang from her chair towards him.

‘There now; Ed may say what he likes, but I believe in luck, I do. It was fated I should meet you the way I did this evening, and I’ve a feeling that if you can’t get my pearls back for me nobody can.’

‘Calm yourself, I pray of you, madame.’ Poirot patted her hand soothingly. ‘Reassure yourself. All will be well. Hercule Poirot will aid you!’

Mr Opalsen turned to the police inspector.

‘There will be no objection to my – er – calling in this gentleman, I suppose?’

‘None at all, sir,’ replied the man civilly, but with complete indifference. ‘Perhaps now your lady’s feeling better she’ll just let us have the facts?’

Mrs Opalsen looked helplessly at Poirot. He led her back to her chair.

‘Seat yourself, madame, and recount to us the whole history without agitating yourself.’

Thus abjured, Mrs Opalsen dried her eyes gingerly, and began.

‘I came upstairs after dinner to fetch my pearls for Mr Poirot here to see. The chambermaid and Célestine were both in the room as usual –’

‘Excuse me, madame, but what do you mean by “as usual”?’

Mr Opalsen explained.

‘I make it a rule that no one is to come into this room unless Célestine, the maid, is there also. The chambermaid does the room in the morning while Célestine is present, and comes in after dinner to turn down the beds under the same conditions; otherwise she never enters the room.’

‘Well, as I was saying,’ continued Mrs Opalsen, ‘I came up. I went to the drawer here’ – she indicated the bottom right-hand drawer of the knee-hole dressing-table – ‘took out my jewel-case and unlocked it. It seemed quite as usual – but the pearls were not there!’

The inspector had been busy with his notebook. ‘When had you last seen them?’ he asked.

‘They were there when I went down to dinner.’

‘You are sure?’

‘Quite sure. I was uncertain whether to wear them or not, but in the end I decided on the emeralds, and put them back in the jewel-case.’

‘Who locked up the jewel-case?’

‘I did. I wear the key on a chain round my neck.’ She held it up as she spoke.

The inspector examined it, and shrugged his shoulders.

‘The thief must have had a duplicate key. No difficult matter. The lock is quite a simple one. What did you do after you’d locked the jewel-case?’

‘I put it back in the bottom drawer where I always keep it.’

‘You didn’t lock the drawer?’

‘No, I never do. My maid remains in the room till I come up, so there’s no need.’

The inspector’s face grew greyer.

‘Am I to understand that the jewels were there when you went down to dinner, and that since then the maid has not left the room?’

Suddenly, as though the horror of her own situation for the first time burst upon her, Célestine uttered a piercing shriek, and, flinging herself upon Poirot, poured out a torrent of incoherent French.

The suggestion was infamous! That she should be suspected of robbing Madame! The police were well known to be of a stupidity incredible! But Monsieur, who was a Frenchman –

‘A Belgian,’ interjected Poirot, but Célestine paid no attention to the correction.

Monsieur would not stand by and see her falsely accused, while that infamous chambermaid was allowed to go scot-free. She had never liked her – a bold, red-faced thing – a born thief. She had said from the first that she was not honest. And had kept a sharp watch over her too, when she was doing Madame’s room! Let those idiots of policemen search her, and if they did not find Madame’s pearls on her it would be very surprising!

Although this harangue was uttered in rapid and virulent French, Célestine had interlarded it with a wealth of gesture, and the chambermaid realized at least a part of her meaning. She reddened angrily.

‘If that foreign woman’s saying I took the pearls, it’s a lie!’ she declared heatedly. ‘I never so much as saw them.’

‘Search her!’ screamed the other. ‘You will find it is as I say.’

‘You’re a liar – do you hear?’ said the chambermaid, advancing upon her. ‘Stole ’em yourself, and want to put it on me. Why, I was only in the room about three minutes before the lady came up, and then you were sitting here the whole time, as you always do, like a cat watching a mouse.’

The inspector looked across inquiringly at Célestine. ‘Is that true? Didn’t you leave the room at all?’

‘I did not actually leave her alone,’ admitted Célestine reluctantly, ‘but I went into my own room through the door here twice – once to fetch a reel of cotton, and once for my scissors. She must have done it then.’

‘You wasn’t gone a minute,’ retorted the chambermaid angrily. ‘Just popped out and in again. I’d be glad if the police would search me. I’ve nothing to be afraid of.’

At this moment there was a tap at the door. The inspector went to it. His face brightened when he saw who it was.

‘Ah!’ he said. ‘That’s rather fortunate. I sent for one of our female searchers, and she’s just arrived. Perhaps if you wouldn’t mind going into the room next door.’

He looked at the chambermaid, who stepped across the threshold with a toss of her head, the searcher following her closely.

The French girl had sunk sobbing into a chair. Poirot was looking round the room, the main features of which I have made clear by a sketch.

‘Where does that door lead?’ he inquired, nodding his head towards the one by the window.

‘Into the next apartment, I believe,’ said the inspector. ‘It’s bolted, anyway, on this side.’

Poirot walked across to it, tried it, then drew back the bolt and tried it again.

‘And on the other side as well,’ he remarked. ‘Well, that seems to rule out that.’

He walked over to the windows, examining each of them in turn.

‘And again – nothing. Not even a balcony outside.’

‘Even if there were,’ said the inspector impatiently, ‘I don’t see how that would help us, if the maid never left the room.’

‘Évidemment,’ said Poirot, not disconcerted. ‘As Mademoiselle is positive she did not leave the room –’

He was interrupted by the reappearance of the chambermaid and the police searcher.

‘Nothing,’ said the latter laconically.

‘I should hope not, indeed,’ said the chambermaid virtuously. ‘And that French hussy ought to be ashamed of herself taking away an honest girl’s character.’

‘There, there, my girl; that’s all right,’ said the inspector, opening the door. ‘Nobody suspects you. You go along and get on with your work.’

The chambermaid went unwillingly.