Полная версия:

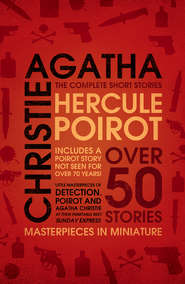

Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories

Poirot made a grimace.

‘But they did not vanish absolutely, since I gather that they were sold in small parcels within half an hour of the docking of the Olympia! Well, undoubtedly the next thing is for me to see Mr Ridgeway.’

‘I was about to suggest that you should lunch with me at the “Cheshire Cheese”. Philip will be there. He is meeting me, but does not yet know that I have been consulting you on his behalf.’

We agreed to this suggestion readily enough, and drove there in a taxi.

Mr Philip Ridgeway was there before us, and looked somewhat surprised to see his fiancée arriving with two complete strangers. He was a nice-looking young fellow, tall and spruce, with a touch of greying hair at the temples, though he could not have been much over thirty.

Miss Farquhar went up to him and laid her hand on his arm.

‘You must forgive me acting without consulting you, Philip,’ she said. ‘Let me introduce you to Monsieur Hercule Poirot, of whom you must often have heard, and his friend, Captain Hastings.’

Ridgeway looked very astonished.

‘Of course I have heard of you, Monsieur Poirot,’ he said, as he shook hands. ‘But I had no idea that Esmée was thinking of consulting you about my – our trouble.’

‘I was afraid you would not let me do it, Philip,’ said Miss Farquhar meekly.

‘So you took care to be on the safe side,’ he observed, with a smile. ‘I hope Monsieur Poirot will be able to throw some light on this extraordinary puzzle, for I confess frankly that I am nearly out of my mind with worry and anxiety about it.’

Indeed, his face looked drawn and haggard and showed only too clearly the strain under which he was labouring.

‘Well, well,’ said Poirot. ‘Let us lunch, and over lunch we will put our heads together and see what can be done. I want to hear Mr Ridgeway’s story from his own lips.’

Whilst we discussed the excellent steak and kidney pudding of the establishment, Philip Ridgeway narrated the circumstances leading to the disappearance of the bonds. His story agreed with that of Miss Farquhar in every particular. When he had finished, Poirot took up the thread with a question.

‘What exactly led you to discover that the bonds had been stolen, Mr Ridgeway?’

He laughed rather bitterly.

‘The thing stared me in the face, Monsieur Poirot. I couldn’t have missed it. My cabin trunk was half out from under the bunk and all scratched and cut about where they’d tried to force the lock.’

‘But I understood that it had been opened with a key?’

‘That’s so. They tried to force it, but couldn’t. And in the end, they must have got it unlocked somehow or other.’

‘Curious,’ said Poirot, his eyes beginning to flicker with the green light I knew so well. ‘Very curious! They waste much, much time trying to prise it open, and then – sapristi! they find they have the key all the time – for each of Hubbs’s locks are unique.’

‘That’s just why they couldn’t have had the key. It never left me day or night.’

‘You are sure of that?’

‘I can swear to it, and besides, if they had had the key or a duplicate, why should they waste time trying to force an obviously unforceable lock?’

‘Ah! there is exactly the question we are asking ourselves! I venture to prophesy that the solution, if we ever find it, will hinge on that curious fact. I beg of you not to assault me if I ask you one more question: Are you perfectly certain that you did not leave the trunk unlocked?’

Philip Ridgeway merely looked at him, and Poirot gesticulated apologetically.

‘Ah, but these things can happen, I assure you! Very well, the bonds were stolen from the trunk. What did the thief do with them? How did he manage to get ashore with them?’

‘Ah!’ cried Ridgeway. ‘That’s just it. How? Word was passed to the Customs authorities, and every soul that left the ship was gone over with a toothcomb!’

‘And the bonds, I gather, made a bulky package?’

‘Certainly they did. They could hardly have been hidden on board – and anyway we know they weren’t, because they were offered for sale within half an hour of the Olympia’s arrival, long before I got the cables going and the numbers sent out. One broker swears he bought some of them even before the Olympia got in. But you can’t send bonds by wireless.’

‘Not by wireless, but did any tug come alongside?’

‘Only the official ones, and that was after the alarm was given when everyone was on the look-out. I was watching out myself for their being passed over to someone that way. My God, Monsieur Poirot, this thing will drive me mad! People are beginning to say I stole them myself.’

‘But you also were searched on landing, weren’t you?’ asked Poirot gently.

‘Yes.’

The young man stared at him in a puzzled manner.

‘You do not catch my meaning, I see,’ said Poirot, smiling enigmatically. ‘Now I should like to make a few inquiries at the Bank.’

Ridgeway produced a card and scribbled a few words on it.

‘Send this in and my uncle will see you at once.’

Poirot thanked him, bade farewell to Miss Farquhar, and together we started out for Threadneedle Street and the head office of the London and Scottish Bank. On production of Ridgeway’s card, we were led through the labyrinth of counters and desks, skirting paying-in clerks and paying-out clerks and up to a small office on the first floor where the joint general managers received us. They were two grave gentlemen, who had grown grey in the service of the Bank. Mr Vavasour had a short white beard, Mr Shaw was clean shaven.

‘I understand you are strictly a private inquiry agent?’ said Mr Vavasour. ‘Quite so, quite so. We have, of course, placed ourselves in the hands of Scotland Yard. Inspector McNeil has charge of the case. A very able officer, I believe.’

‘I am sure of it,’ said Poirot politely. ‘You will permit a few questions, on your nephew’s behalf? About this lock, who ordered it from Hubbs’s?’

‘I ordered it myself,’ said Mr Shaw. ‘I would not trust to any clerk in the matter. As to the keys, Mr Ridgeway had one, and the other two are held by my colleague and myself.’

‘And no clerk has had access to them?’

Mr Shaw turned inquiringly to Mr Vavasour.

‘I think I am correct in saying that they have remained in the safe where we placed them on the 23rd,’ said Mr Vavasour. ‘My colleague was unfortunately taken ill a fortnight ago – in fact on the very day that Philip left us. He has only just recovered.’

‘Severe bronchitis is no joke to a man of my age,’ said Mr Shaw ruefully. ‘But I’m afraid Mr Vavasour has suffered from the hard work entailed by my absence, especially with this unexpected worry coming on top of everything.’

Poirot asked a few more questions. I judged that he was endeavouring to gauge the exact amount of intimacy between uncle and nephew. Mr Vavasour’s answers were brief and punctilious. His nephew was a trusted official of the Bank, and had no debts or money difficulties that he knew of. He had been entrusted with similar missions in the past. Finally we were politely bowed out.

‘I am disappointed,’ said Poirot, as we emerged into the street.

‘You hoped to discover more? They are such stodgy old men.’

‘It is not their stodginess which disappoints me, mon ami. I do not expect to find in a Bank manager, a “keen financier with an eagle glance”, as your favourite works of fiction put it. No, I am disappointed in the case – it is too easy!’

‘Easy?’

‘Yes, do you not find it almost childishly simple?’

‘You know who stole the bonds?’

‘I do.’

‘But then – we must – why –’

‘Do not confuse and fluster yourself, Hastings. We are not going to do anything at present.’

‘But why? What are you waiting for?’

‘For the Olympia. She is due on her return trip from New York on Tuesday.’

‘But if you know who stole the bonds, why wait? He may escape.’

‘To a South Sea island where there is no extradition? No, mon ami, he would find life very uncongenial there. As to why I wait – eh bien, to the intelligence of Hercule Poirot the case is perfectly clear, but for the benefit of others, not so greatly gifted by the good God – the Inspector, McNeil, for instance – it would be as well to make a few inquiries to establish the facts. One must have consideration for those less gifted than oneself.’

‘Good Lord, Poirot! Do you know, I’d give a considerable sum of money to see you make a thorough ass of yourself – just for once. You’re so confoundedly conceited!’

‘Do not enrage yourself, Hastings. In verity, I observe that there are times when you almost detest me! Alas, I suffer the penalties of greatness!’

The little man puffed out his chest, and sighed so comically that I was forced to laugh.

Tuesday saw us speeding to Liverpool in a first-class carriage of the L and NWR. Poirot had obstinately refused to enlighten me as to his suspicions – or certainties. He contented himself with expressing surprise that I, too, was not equally au fait with the situation. I disdained to argue, and entrenched my curiosity behind a rampart of pretended indifference.

Once arrived at the quay alongside which lay the big transatlantic liner, Poirot became brisk and alert. Our proceedings consisted in interviewing four successive stewards and inquiring after a friend of Poirot’s who had crossed to New York on the 23rd.

‘An elderly gentleman, wearing glasses. A great invalid, hardly moved out of his cabin.’

The description appeared to tally with one Mr Ventnor who had occupied the cabin C24 which was next to that of Philip Ridgeway. Although unable to see how Poirot had deduced Mr Ventnor’s existence and personal appearance, I was keenly excited.

‘Tell me,’ I cried, ‘was this gentleman one of the first to land when you got to New York?’

The steward shook his head.

‘No, indeed, sir, he was one of the last off the boat.’ I retired crestfallen, and observed Poirot grinning at me. He thanked the steward, a note changed hands, and we took our departure.

‘It’s all very well,’ I remarked heatedly, ‘but that last answer must have damned your precious theory, grin as you please!’

‘As usual, you see nothing, Hastings. That last answer is, on the contrary, the coping-stone of my theory.’

I flung up my hands in despair.

‘I give it up.’

When we were in the train, speeding towards London, Poirot wrote busily for a few minutes, sealing up the result in an envelope.

‘This is for the good Inspector McNeil. We will leave it at Scotland Yard in passing, and then to the Rendezvous Restaurant, where I have asked Miss Esmée Farquhar to do us the honour of dining with us.’

‘What about Ridgeway?’

‘What about him?’ asked Poirot with a twinkle.

‘Why, you surely don’t think – you can’t –’

‘The habit of incoherence is growing upon you, Hastings. As a matter of fact I did think. If Ridgeway had been the thief – which was perfectly possible – the case would have been charming; a piece of neat methodical work.’

‘But not so charming for Miss Farquhar.’

‘Possibly you are right. Therefore all is for the best. Now, Hastings, let us review the case. I can see that you are dying to do so. The sealed package is removed from the trunk and vanishes, as Miss Farquhar puts it, into thin air. We will dismiss the thin air theory, which is not practicable at the present stage of science, and consider what is likely to have become of it. Everyone asserts the incredulity of its being smuggled ashore –’

‘Yes, but we know –’

‘You may know, Hastings, I do not. I take the view that, since it seemed incredible, it was incredible. Two possibilities remain: it was hidden on board – also rather difficult – or it was thrown overboard.’

‘With a cork on it, do you mean?’

‘Without a cork.’

I stared.

‘But if the bonds were thrown overboard, they couldn’t have been sold in New York.’

‘I admire your logical mind, Hastings. The bonds were sold in New York, therefore they were not thrown overboard. You see where that leads us?’

‘Where we were when we started.’

‘Jamais de la vie! If the package was thrown overboard and the bonds were sold in New York, the package could not have contained the bonds. Is there any evidence that the package did contain the bonds? Remember, Mr Ridgeway never opened it from the time it was placed in his hands in London.’

‘Yes, but then –’

Poirot waved an impatient hand.

‘Permit me to continue. The last moment that the bonds are seen as bonds is in the office of the London and Scottish Bank on the morning of the 23rd. They reappear in New York half an hour after the Olympia gets in, and according to one man, whom nobody listens to, actually before she gets in. Supposing then, that they have never been on the Olympia at all? Is there any other way they could get to New York? Yes. The Gigantic leaves Southampton on the same day as the Olympia, and she holds the record for the Atlantic. Mailed by the Gigantic, the bonds would be in New York the day before the Olympia arrived. All is clear, the case begins to explain itself. The sealed packet is only a dummy, and the moment of its substitution must be in the office in the bank. It would be an easy matter for any of the three men present to have prepared a duplicate package which could be substituted for the genuine one. Très bien, the bonds are mailed to a confederate in New York, with instructions to sell as soon as the Olympia is in, but someone must travel on the Olympia to engineer the supposed moment of robbery.’

‘But why?’

‘Because if Ridgeway merely opens the packet and finds it a dummy, suspicion flies at once to London. No, the man on board in the cabin next door does his work, pretends to force the lock in an obvious manner so as to draw immediate attention to the theft, really unlocks the trunk with a duplicate key, throws the package overboard and waits until the last to leave the boat. Naturally he wears glasses to conceal his eyes, and is an invalid since he does not want to run the risk of meeting Ridgeway. He steps ashore in New York and returns by the first boat available.’

‘But who – which was he?’

‘The man who had a duplicate key, the man who ordered the lock, the man who has not been severely ill with bronchitis at his home in the country – enfin, the “stodgy” old man, Mr Shaw! There are criminals in high places sometimes, my friend. Ah, here we are, mademoiselle, I have succeeded! You permit?’

And, beaming, Poirot kissed the astonished girl lightly on either cheek!

10 The Adventure of the Cheap Flat

‘The Adventure of the Cheap Flat’ was first published in The Sketch, 9 May 1923.

So far, in the cases which I have recorded, Poirot’s investigations have started from the central fact, whether murder or robbery, and have proceeded from thence by a process of logical deduction to the final triumphant unravelling. In the events I am now about to chronicle a remarkable chain of circumstances led from the apparently trivial incidents which first attracted Poirot’s attention to the sinister happenings which completed a most unusual case.

I had been spending the evening with an old friend of mine, Gerald Parker. There had been, perhaps, about half a dozen people there besides my host and myself, and the talk fell, as it was bound to do sooner or later wherever Parker found himself, on the subject of house-hunting in London. Houses and flats were Parker’s special hobby. Since the end of the War, he had occupied at least half a dozen different flats and maisonettes. No sooner was he settled anywhere than he would light unexpectedly upon a new find, and would forthwith depart bag and baggage. His moves were nearly always accomplished at a slight pecuniary gain, for he had a shrewd business head, but it was sheer love of the sport that actuated him, and not a desire to make money at it. We listened to Parker for some time with the respect of the novice for the expert. Then it was our turn, and a perfect babel of tongues was let loose. Finally the floor was left to Mrs Robinson, a charming little bride who was there with her husband. I had never met them before, as Robinson was only a recent acquaintance of Parker’s.

‘Talking of flats,’ she said, ‘have you heard of our piece of luck, Mr Parker? We’ve got a flat – at last! In Montagu Mansions.’

‘Well,’ said Parker, ‘I’ve always said there are plenty of flats – at a price!’

‘Yes, but this isn’t at a price. It’s dirt cheap. Eighty pounds a year!’

‘But – but Montagu Mansions is just off Knightsbridge, isn’t it? Big handsome building. Or are you talking of a poor relation of the same name stuck in the slums somewhere?’

‘No, it’s the Knightsbridge one. That’s what makes it so wonderful.’

‘Wonderful is the word! It’s a blinking miracle. But there must be a catch somewhere. Big premium, I suppose?’

‘No premium!’

‘No prem – oh, hold my head, somebody!’ groaned Parker.

‘But we’ve got to buy the furniture,’ continued Mrs Robinson.

‘Ah!’ Parker bristled up. ‘I knew there was a catch!’

‘For fifty pounds. And it’s beautifully furnished!’

‘I give it up,’ said Parker. ‘The present occupants must be lunatics with a taste for philanthropy.’

Mrs Robinson was looking a little troubled. A little pucker appeared between her dainty brows.

‘It is queer, isn’t it? You don’t think that – that – the place is haunted?’

‘Never heard of a haunted flat,’ declared Parker decisively.

‘No-o.’ Mrs Robinson appeared far from convinced. ‘But there were several things about it all that struck me as – well, queer.’

‘For instance –’ I suggested.

‘Ah,’ said Parker, ‘our criminal expert’s attention is aroused! Unburden yourself to him, Mrs Robinson. Hastings is a great unraveller of mysteries.’

I laughed, embarrassed, but not wholly displeased with the rôle thrust upon me.

‘Oh, not really queer, Captain Hastings, but when we went to the agents, Stosser and Paul – we hadn’t tried them before because they only have the expensive Mayfair flats, but we thought at any rate it would do no harm – everything they offered us was four and five hundred a year, or else huge premiums, and then, just as we were going, they mentioned that they had a flat at eighty, but that they doubted if it would be any good our going there, because it had been on their books some time and they had sent so many people to see it that it was almost sure to be taken – “snapped up” as the clerk put it – only people were so tiresome in not letting them know, and then they went on sending, and people get annoyed at being sent to a place that had, perhaps, been let some time.’

Mrs Robinson paused for some much needed breath, and then continued:

‘We thanked him, and said that we quite understood it would probably be no good, but that we should like an order all the same – just in case. And we went there straight away in a taxi, for, after all, you never know. No 4 was on the second floor, and just as we were waiting for the lift, Elsie Ferguson – she’s a friend of mine, Captain Hastings, and they are looking for a flat too – came hurrying down the stairs. “Ahead of you for once, my dear,” she said. “But it’s no good. It’s already let.” That seemed to finish it, but – well, as John said, the place was very cheap, we could afford to give more, and perhaps if we offered a premium. A horrid thing to do, of course, and I feel quite ashamed of telling you, but you know what flat-hunting is.’

I assured her that I was well aware that in the struggle for house-room the baser side of human nature frequently triumphed over the higher, and that the well-known rule of dog eat dog always applied.

‘So we went up and, would you believe it, the flat wasn’t let at all. We were shown over it by the maid, and then we saw the mistress, and the thing was settled then and there. Immediate possession and fifty pounds for the furniture. We signed the agreement next day, and we are to move in tomorrow!’ Mrs Robinson paused triumphantly.

‘And what about Mrs Ferguson?’ asked Parker. ‘Let’s have your deductions, Hastings.’

‘“Obvious, my dear Watson,”’ I quoted lightly. ‘She went to the wrong flat.’

‘Oh, Captain Hastings, how clever of you!’ cried Mrs Robinson admiringly.

I rather wished Poirot had been there. Sometimes I have the feeling that he rather underestimates my capabilities.

The whole thing was rather amusing, and I propounded the thing as a mock problem to Poirot on the following morning. He seemed interested, and questioned me rather narrowly as to the rents of flats in various localities.

‘A curious story,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘Excuse me, Hastings, I must take a short stroll.’

When he returned, about an hour later, his eyes were gleaming with a peculiar excitement. He laid his stick on the table, and brushed the nap of his hat with his usual tender care before he spoke.

‘It is as well, mon ami, that we have no affairs of moment on hand. We can devote ourselves wholly to the present investigation.’

‘What investigation are you talking about?’

‘The remarkable cheapness of your friend, Mrs Robinson’s, new flat.’

‘Poirot, you are not serious!’

‘I am most serious. Figure to yourself, my friend, that the real rent of those flats is £350. I have just ascertained that from the landlord’s agents. And yet this particular flat is being sublet at eighty pounds! Why?’

‘There must be something wrong with it. Perhaps it is haunted, as Mrs Robinson suggested.’

Poirot shook his head in a dissatisfied manner.

‘Then again how curious it is that her friend tells her the flat is let, and, when she goes up, behold, it is not so at all!’

‘But surely you agree with me that the other woman must have gone to the wrong flat. That is the only possible solution.’

‘You may or may not be right on that point, Hastings. The fact still remains that numerous other applicants were sent to see it, and yet, in spite of its remarkable cheapness, it was still in the market when Mrs Robinson arrived.’

‘That shows that there must be something wrong about it.’

‘Mrs Robinson did not seem to notice anything amiss. Very curious, is it not? Did she impress you as being a truthful woman, Hastings?’

‘She was a delightful creature!’

‘Évidemment! since she renders you incapable of replying to my question. Describe her to me, then.’

‘Well, she’s tall and fair; her hair’s really a beautiful shade of auburn –’

‘Always you have had a penchant for auburn hair!’ murmured Poirot. ‘But continue.’

‘Blue eyes and a very nice complexion and – well, that’s all, I think,’ I concluded lamely.

‘And her husband?’

‘Oh, he’s quite a nice fellow – nothing startling.’

‘Dark or fair?’

‘I don’t know – betwixt and between, and just an ordinary sort of face.’

Poirot nodded.

‘Yes, there are hundreds of these average men – and anyway, you bring more sympathy and appreciation to your description of women. Do you know anything about these people? Does Parker know them well?’

‘They are just recent acquaintances, I believe. But surely, Poirot, you don’t think for an instant –’

Poirot raised his hand.

‘Tout doucement, mon ami. Have I said that I think anything? All I say is – it is a curious story. And there is nothing to throw light upon it; except perhaps the lady’s name, eh, Hastings?’

‘Her name is Stella,’ I said stiffly, ‘but I don’t see –’

Poirot interrupted me with a tremendous chuckle. Something seemed to be amusing him vastly.