Полная версия:

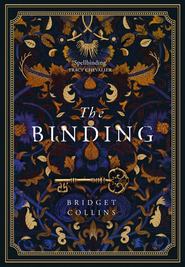

The Binding

‘Whatever happened? She was bound, that’s what happened! Now, you move out of the way, or I swear I’ll burn you along with everything else—’ He lunged at me and dragged me forwards. I stumbled away from the door, surprised by the strength of his grip; then I flung my arm up to break his hold. I staggered to the side but by the time I got my balance someone had grabbed me from behind. The other man swung his torch in front of me as if I was an animal. The heat prickled on my cheeks and I blinked away stinging tears. ‘And you,’ he shouted, through the doorway, ‘you come out too. You come out and we won’t hurt you.’

I tried to pull away from whoever was holding me. ‘You mean you’ll just leave us out here in the snow? Miles from anywhere? She’s an old woman.’

‘Shut up!’ He turned on me. ‘I’m being kind, warning you at all.’

I wanted to throttle him. I forced myself to take a deep breath. ‘Look – you can’t do this. You could be deported – you don’t want to risk that.’

‘For burning a binder’s house to the ground? I’ve got ten friends’ll swear I was in the tavern the whole night. Now, get the old bitch out here or she’ll get smoked into a kipper with the rest.’

The front door slammed. A bolt shot home.

Melted snow ran off the roof in a sudden dribble, as if a pool had formed and overflowed. The breeze lifted and died again. I thought I heard it whine in the broken window. I swallowed. ‘Seredith?’

She didn’t answer. I pulled away from the man who’d been holding me. He let me go without a struggle.

‘Seredith. Open the door. Please.’ I leant sideways to peer through the jagged space where the window had been. She was sitting on the stairs like a child, her legs crossed neatly at the ankles. She didn’t look up. ‘What are you doing? Seredith?’

She murmured something.

‘What? Please, let me in—’

‘That’s it. The bitch wants to burn.’ There was a strident note in his voice, like bravado; but when I looked back at him he gave me a wide rotten-toothed grin. ‘She’s made her choice. Now get out of the way.’ He lurched forwards and sloshed oil on the wall by my feet. The smell rose like a fog, thick and real.

‘Don’t – you can’t – please!’ He went on grinning at me, unblinking. I turned and hammered at the last shards of glass in the window, smashing them away with the side of my fist; but the window was too narrow to get through. ‘Seredith, come out! They’re going to set the house on fire, please.’

She didn’t move. I would have thought she couldn’t hear me, except that her shoulders rose a little when I said please.

‘You can’t set fire to the house while she’s in it. That’s murder.’ My voice was high and hoarse.

‘Get out of the way.’ But he didn’t wait for me to move. Oil splashed on to my trousers as he went past. He poured the last dregs against the side wall and stood back. The man with the torch was watching, his expression open and interested, like a schoolboy’s.

Maybe it wouldn’t be enough. Maybe the snow on the roof would quench it, or the walls would be too thick and too damp. But Seredith was old, and the smoke would be enough to kill her, if she was inside.

‘Hey, Baldwin. Get the other bucket. Round the side.’ He pointed.

‘Please. Please don’t do this.’ But I knew it was no good. I spun round and threw myself against the door. I pounded on the wood with my fists. ‘Seredith! Open the door. Damn you, open the door.’

Someone caught my collar and pulled me back. I choked and nearly fell.

‘Good. Keep him back. Now.’

The man with the torch grunted and stepped forwards. I scrabbled desperately to break free. The seam of my shirt ripped and I almost fell into the space between the torch-flames and the door. The smell of oil was so strong I could taste it. It was on me, on my trousers and hands; the smallest leap of a spark and I’d be on fire. The burning torch hovered in front of my eyes, a spitting mass of talons and tongues.

Something thudded into my back. I’d walked backwards into the door. I leant against it. Nowhere to go now.

The man raised the torch like a staff and tilted it until it was right in front of my face. Then he lowered it. I watched it flicker, almost touching the base of the wall, almost close enough to catch.

‘No.’

My own voice; but not my own. My blood rose and sang in my ears like a flood, so loud I couldn’t hear myself think.

‘Do this and you will be cursed,’ I said, and in the sudden quiet it was as though another voice spoke underneath mine. ‘Kill with fire and you will perish in fire. Burn in hatred and you will burn.’

No one answered. No one moved.

‘If you do this, your souls will be stained with blood and ash. Everything you touch will go grey and wither. Everyone you touch will fall ill or run mad or die.’

A sound: faint, faraway, like something drawing closer. But the voice coming from inside me wouldn’t let me pause to listen. ‘You will end hated and alone,’ it said. ‘There will be no forgiveness, ever.’

Quietness spread out around me like a ripple in a pond, deadening the hiss of the wind and the scratch of the flames. But inside that quiet there was something new, ticking, like drying wood or leaves falling.

The men stared at me. I looked round, meeting their eyes, letting the other voice look through me. My hand rose to point at the man who had threatened me, steady as a prophet’s. ‘Go.’

He hesitated. The ticking broadened into a crackle, then a hiss, then a roar.

Rain.

It fell in ropes, as sudden as an ambush, blinding me, driving through hair and clothes in seconds. Icy water ran down the back of my neck and sprayed off my nose when I gasped with the shock of it. The man swung his torch sideways to catch the shelter of the overhanging roof, but the wind blew a curtain of rain over it, and then there was no light at all. There was shouting, a few stifled, panicked cries, and the sounds of a man stumbling in the dark. ‘He called down the rain – fuck this, let’s go – the magic—’

I blinked, but there were only blurred shadows, running and disappearing like wraiths. Someone called, someone answered, someone grunted and swore as he tripped and struggled to his feet; and then the noise retreated, I heard a far-off mutter of voices and horses, and they were gone.

I shut my eyes. I was soaked to the skin. The marsh hissed and rumbled under the rain, answering, echoing. The thatch whispered its own note as the wind hummed through the broken window. There was the smell of mud and reeds and melted snow.

I was cold. A spasm of shivering took hold of me and I leant forward, bracing myself as if it came from outside. When it was over I blinked the water off my eyelashes and blew the strings of rain away from my mouth. The dark had lessened, and now I could make out trembling, silvery edges to things: the barn, the road, the horizon.

I turned round and stared through the window. Even now it made my neck tingle, to turn my back on the vast emptiness where the road was. But I’d heard them go. I called softly, ‘Seredith? They’ve gone. Let me in.’

I wasn’t sure if I could really see her, or whether my brain was inventing the ghostly blur in the darkness. I wiped the water out of my eyes and tried to make her out. She was there, sitting on the stairs. I leant as close to the edge of the broken glass as I could. ‘Seredith. It’s all right. Open the door.’

She didn’t move. I don’t know how long I stood there. I murmured to her as if I was trying to tame an animal: the same words, over and over again. I started to forget what was my voice and what was the rain. I was so cold I went into a sort of dream, where I was the marsh and the house as well as myself, where I was slippery wet wood and claggy mud … When at last the bolt was shot back, I was so stiff and shrammed that I didn’t react straight away.

Seredith said, ‘Come in, then.’

I limped inside and stood dripping on the floor. Seredith rummaged in the sideboard; I heard the scratching of match after match as she tried to light the lamp. At last I crossed to her and gently took the box. We both jumped at my touch. I didn’t look at her until the lamp was burning and I’d put the glass chimney over the flame.

She was trembling, and her hair was sticking out in a clump; but when she met my eyes, she gave me a wry almost-smile that told me she knew who I was. She reached for the lamp.

‘Seredith …’

‘I know. I shall go to bed, or I’ll catch my death.’

That wasn’t what I’d been going to say. I nodded.

‘You’d better go too.’ She added, too quickly, ‘You’re sure they’ve gone?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good.’

Silence. She stared at the lamp, and in the soft light her face could have been young. At last she said, ‘Thank you, Emmett.’

I didn’t answer.

‘Without you, they would have burnt the house down before the rain came.’

‘Why didn’t you—’

‘I was so afraid when I heard them knocking.’ She stopped. She took a pace towards the staircase, and turned back. ‘When they came, I dreamt … I thought they were the Crusade. There hasn’t been a Crusade here for sixty years, but … I remember them coming for us. I must have been your age. And my master …’

‘The Crusade?’

‘Never mind. Those days are over. Now it’s only a few peasants, here and there, that hate us enough to murder us …’ She laughed a little. I’d never heard her say peasants like that, with contempt.

Something inside me tipped. I said, slowly, ‘But they didn’t want to murder us. Not really. They wanted to burn the house.’ A pause. The flame bobbed, so I couldn’t tell if her expression had changed. ‘Why did you lock yourself in, Seredith?’

She reached for the banister and began to climb the stairs.

‘Seredith.’ My arms ached with the effort to stop myself reaching for her. ‘You could have died. I could have died, trying to get you out. Why the hell did you lock yourself in?’

‘Because of the books,’ she said, turning so suddenly I was scared she’d fall. ‘Why do you think, boy? Because the books have to be kept safe.’

‘But—’

‘And if the books burn, I will burn with them. Do you understand?’

I shook my head.

She looked at me for a long time. She seemed about to say something else. But then she shivered so violently she had to steady herself, and when the spasm had passed she seemed exhausted. ‘Not now,’ she said. Her voice was hoarse, as if she’d come to the last of her breath. ‘Good night.’

I listened to her footsteps climb to the landing and cross to the room where she slept. The rain swirled through the broken window and rattled on the floor, but I couldn’t bring myself to care.

I was aching all over with cold, and my head was spinning with tiredness; but when I shut my eyes I saw flames spitting and clawing at me. The noise of the rain separated into different notes: the percussive hiss of water on the roof, the whisper of the wind, human voices … I knew they weren’t real, but I could hear distinct words, as if everyone I had ever known had surrounded the house and was calling to me. It was fatigue, only fatigue, but I didn’t want to fall asleep. I wanted … Most of all I wanted not to be alone; but that was the one thing I couldn’t have.

I had to get warm. My mother would have parcelled me up in a blanket and wrapped her arms round me until I stopped shivering; then she would have made me hot tea and brandy, sent me to bed and sat beside me while I drank it. The familiar ache of homesickness threatened to overwhelm me. I went into the workshop and lit the stove. Outside there was a hint of light, a crack between the clouds and the horizon; it was later than I’d realised.

It occurred to me, vaguely, that I had saved Seredith’s life.

I brewed tea, and drank it. The flames dancing in my head began to subside. The voices grew fainter as the rain slackened. The stove creaked and clicketed and smelt of warm metal. I sat on the floor, leaning against the plan chest, with my legs spread out in front of me. From this angle, and in this light, the workshop looked like a cave: mysterious, looming, the knobs and screws of the presses transformed into strange rock formations. The shadow of the board cutter on the wall looked like a man’s face. I rolled my head round, taking it all in, and for a second I was filled with a fierce pleasure to have saved it all: my workshop, my things, my place.

The door at the end of the room was ajar.

I blinked. At first I thought it was a trick of the light. I put down my cold mug of tea and leant forward, and saw the gap between the door and the jamb. It was the door on the left of the stove: not the room where Seredith took people, but the other door, the one that led down into the dark.

I almost kicked it shut. I could have done that, left it unlocked but closed, and gone to bed. I almost did. I reached out gently with my foot, but instead of pushing it shut I edged it open.

Blackness. An empty shelf just inside, and beyond that a flight of stairs going down. Nothing more than I’d seen before. Nothing like the bare light-filled room behind the other door, except for the cold that breathed from it.

I stood up and reached for the lamp. I wasn’t sleepy any more. Tension pricked in my fingertips and itched between my shoulder blades. I pushed the door wide open and went down into the dark.

It smelt of damp. That was the first thing I noticed: a thick, muddy scent like rotting reeds. I paused on the stair, my heart speeding up. Damp was almost as bad as fire; it brought mould and wrinkled paper and softened glue. And it smelt of age and dead things, smelt wrong … But as I turned the corner of the staircase and lifted the lamp, what I saw was nothing out of the ordinary: a little room with a table and cupboards, a broom and a bucket, chests that were marked with a stationer’s label. I almost laughed. Just a storeroom. At the far end – although it wasn’t far, only a few steps across – there was a round bronze plate in the wall, like a solid wheel, intricate and decorative. The other walls were piled high with chests and boxes. The air felt as dry as it had upstairs; perhaps I’d imagined the smell.

I turned my head, half thinking I’d heard something. But everything was perfectly still, insulated from the noise of the rain by the dense earth beyond.

I put down the lamp and looked about me. There was a drawer balanced on a pile of boxes, full of broken tools waiting to be repaired or thrown away, and a row of glass bottles filled with dark liquid that looked like dyes or ox gall for marbling paper. I nearly tripped over three fire-buckets of sand. On the table there was a humped parcel wrapped in sackcloth, and some tools. I didn’t recognise them; they were thin, delicate things with edges like fish’s teeth. I brought the lamp closer. Next to the bundle there was another cloth, spread out to cover something. This was where Seredith worked, when I was upstairs in the workshop.

I reached out and unwrapped the bundle, as gently as if it was alive. It was a book-block, neatly sewn, with thick dark endpapers threaded with white, like tiny roots reaching through soil. The blood sang in my fingertips. A book. The first book I had seen, since I’d been here; the first since I was a child, and learned that they were forbidden. But holding it now I felt nothing but a kind of peace.

I brought it to my face and inhaled the smell of paper. I almost opened it to look at the title page; but I was too curious about what was under the other bit of sacking. I put the block down and drew back the cloth. Here was the cover Seredith had been making. For a moment, before I understood what I was seeing, it was beautiful.

The background was black velvet, so fine it absorbed every glint of light and lay on the bench like a piece of solid darkness. The inlay stood out against it like ivory, shining softly, pale gold in the lamplight.

Bones. A skeleton, the spine curled like a row of pearls round pale twigs of legs and arms, and the tiny splinters of toes and fingers. The skull bulged like a mushroom. They were smaller than my outstretched hand, those bones. They were as small and fragile as a bird’s.

But it wasn’t … it hadn’t been a bird. It was a baby.

V

‘Don’t touch it.’

I hadn’t heard Seredith come into the room, but some distant, watchful part of me wasn’t surprised to hear her voice. I didn’t know how long I had been standing there. It was only when I stepped back – carefully, as though there was something here I was afraid to wake – that I felt the stiff chill in my joints, the pins-and-needles in my feet, and knew it had been a long time. In spite of my care I knocked my ankle against a box, but the hollow sound was muffled by the earth beyond the walls.

I said, ‘I wasn’t going to touch it.’

‘Emmett …’

I didn’t answer. The wick of the lamp needed trimming, and the shadows jumped and ducked. The bones gleamed against their bed of black. As the light danced back and forth I could have made myself believe that they were moving; but when at last the flame steadied they lay quiet.

‘It’s only a binding,’ she said. She shifted in the doorway, but I didn’t look at her. ‘It’s mother-of-pearl.’

‘Not real bones.’ It came out like mockery. I hadn’t meant it to, but I was glad, fiercely glad, at the way it cut through the silence.

‘No,’ she said softly, ‘not real bones.’

I stared at the shining intricate shapes on the velvet until my eyes blurred. At last I reached out and pulled the cloth down over them; then I stood looking down at the coarse brown hessian. Here and there, where the weave was loose, I could still see the smooth edge of a femur, the nacreous curve of the skull, a miniature, perfect fingerbone. I imagined her working on them, crafting tiny shapes out of mother-of-pearl. I shut my eyes and listened to my blood pounding, and beyond that the dead quiet of walls and earth.

‘Tell me,’ I said. ‘Tell me what you do.’

The lamp murmured and guttered. Nothing else moved.

‘You know already.’

‘No.’

‘You know, if you think about it.’

I opened my mouth to say no, again; but something caught in my throat. The lamp-flame flared, licked upwards and then sank to a tiny blue bubble. The dark took a step towards me.

‘You bind – people,’ I said. My throat was so dry it hurt to speak; but the silence hurt more. ‘You make people into books.’

‘Yes. But not in the way you mean.’

‘What other way is there?’

She walked towards me. I didn’t turn, but the light from her candle grew stronger, pushing back the shadows. ‘Sit down, Emmett.’

She touched my shoulder. I flinched and spun round, stumbling back into the table. Tools clattered to the floor and skittered away. We stared at each other. She had stepped back too; now she put her candle down on one of the chests, and the flame magnified the trembling of her hand. Wax had spattered the floor; it congealed in a split second, like water turning to milk.

‘Sit down.’ She lifted an open drawer of jars off a box. ‘Here.’

I didn’t want to sit, while she was standing. I held her gaze, and she was the first to look away. She dumped the drawer down again. Then, wearily, she bent to pick up the little tools I’d knocked off the table.

‘You trap them,’ I said. ‘You take people and put them inside books. They leave here … empty.’

‘I suppose, in a way—’

‘You steal their souls.’ My voice cracked. ‘No wonder they’re afraid of you. You lure them here and suck them dry, you take what you want and send them away with nothing. That’s what a book is, isn’t it? A life. A person. And if they burn, they die.’

‘No.’ She straightened up, one hand clutching a tiny wood-handled knife.

I picked up the book on the table and held it out. ‘Look,’ I said, my voice rising and rising, ‘this is a person. Inside there’s a person – out there somewhere they’re walking round dead – it’s evil, what you do, they should have fucking burnt you.’

She slapped me.

Silence. There was a thin high ringing in the air that wasn’t real. Automatic tears rose in my eyes and spilt down my cheeks. I wiped them away with the inside of my wrist. The pain faded to a hot tingling, like salt water drying on my skin. I put the book down and smoothed the endpaper with my palm where I’d rumpled it. The crease would never come out entirely; it stood out like a scar, branching across the corner. I said, ‘I’m sorry.’

Seredith turned away and dropped the knife into the open drawer by my side. ‘Memories,’ she said, at last. ‘Not people, Emmett. We take memories and bind them. Whatever people can’t bear to remember. Whatever they can’t live with. We take those memories and put them where they can’t do any more harm. That’s all books are.’

Finally I met her eyes. Her expression was open, candid, a little weary, like her voice. She made it sound so right – so necessary; like a doctor describing an amputation. ‘Not souls, Emmett,’ she said. ‘Not people. Just memories.’

‘It’s wrong,’ I said, trying to match my tone to hers. Steady, reasonable … but my voice shook and betrayed me. ‘You can’t say it’s right to do that. Who are you to say what they can live with?’

‘We don’t. We help people who come to us and ask for it.’ A flicker of sympathy went over her face as if she knew she’d won. ‘No one has to come, Emmett. They decide. All we do is help them forget.’

It wasn’t that simple. Somehow I knew it wasn’t. But I had no argument to make, no defence against the softness of her voice and her level eyes. ‘What about that?’ I pointed to the child-shape under the sacking. ‘Why would you make a book like that?’

‘Milly’s book? Do you really want to know?’

A shiver went over me, fierce and sudden. I clenched my teeth and didn’t answer.

She walked past me, stared down at the sacking for a moment, and then slid it gently to one side. In her shadow the little skeleton shone bluish.

‘She buried it alive,’ Seredith said. There was no weight to the words, only a quiet precision that left all the feeling to me. ‘She couldn’t go on, she thought she couldn’t go on. And so she wrapped it up, one day when it wouldn’t stop crying, and she laid it on the dung heap and pulled rubbish and manure over it until she couldn’t hear it any more.’

‘Her baby?’

A nod.

I wanted to shut my eyes, but I couldn’t look away. The baby would have lain like that, curled and helpless, trying to cry, trying to breathe. How long would it have taken, before it was just part of the dungheap, rotting with everything else? It was like a horrible fairy tale: bones turned to pearl, earth turned to velvet. But it was true. It was true, and the story was locked in a book, shut away, written on dead pages. My hand tingled where I had smoothed out the endpaper: that thick, veined paper, black as soil.

‘That’s murder,’ I said. ‘Why didn’t the parish constable arrest her?’

‘She kept the child a secret. No one knew about it.’

‘But …’ I stopped. ‘How could you help her? A woman – a girl who killed her own child – like that – you should have …’

‘What should I have done?’

‘Let her suffer! Make her live with it! Remembering is part of the punishment. If you do something evil—’

‘It was her father’s, too. The man who came to burn this book. He was her father, and the child’s.’

For a moment I didn’t understand what she meant. Then I looked away, feeling sick.

There was the rustle of sackcloth as Seredith drew it back over the bones, and the creak of the box as she perched on the edge of it, holding on to the table to steady herself.

At last she said, ‘I’m not being fair to you, Emmett. Sometimes I do turn people away. Very, very rarely. And not because they’ve done something so terrible I can’t help; only because I know they’ll go on doing terrible things. Then, if I’m sure, I will refuse to help them. But it has only happened three times, in more than sixty years. The others, I helped.’