Полная версия:

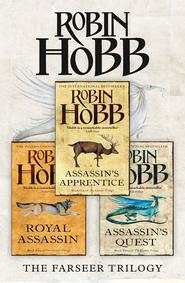

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

‘You the bastid, hey?’

I had heard the word often enough to know it meant me, without grasping the fullness of its meaning. I nodded slowly. The man’s face brightened with interest.

‘Hey,’ he said loudly, no longer speaking to me but to the folk coming and going. ‘Here’s the bastid. Stiff-as-a-stick Chivalry’s by-blow. Looks a fair bit like him, don’t you say? Who’s your mother, boy?’

To their credit, most of the passing people continued to come and go, with no more than a curious stare at the six-year-old sitting by the wall. But the cask-man’s question was evidently of great interest, for more than a few heads turned, and several tradesmen who had just exited from the kitchen drew nearer to hear the answer.

But I did not have an answer. Mother had been mother, and whatever I had known of her was already fading. So I made no reply, but only stared up at him.

‘Hey. What’s your name then, boy?’ And turning to his audience, he confided, ‘I heard he ain’t got no name. No high-flown royal name to shape him, nor even a cottage name to scold him by. That right, boy? You got a name?’

The group of onlookers was growing. A few showed pity in their eyes, but none interfered. Some of what I was feeling passed to Nosy, who dropped over onto his side and showed his belly in supplication while thumping his tail in that ancient canine signal that always means, ‘I’m only a puppy. I cannot defend myself. Have mercy.’ Had they been dogs they would have sniffed me over and then drawn back. But humans have no such inbred courtesies. So when I didn’t answer, the man drew a step nearer, and repeated, ‘You got a name, boy?’

I stood slowly, and the wall that had been warm against my back a moment ago was now a chill barrier to retreat. At my feet, Nosy squirmed in the dust on his back and let out a pleading whine. ‘No,’ I said softly, and when the man made as if to lean closer to hear my words, ‘NO!’ I shouted, and repelled at him, while crabbing sideways along the wall. I saw him stagger a step backwards, losing his grip on his cask so that it fell to the cobbled path and cracked open. No one in the crowd could have understood what had happened. I certainly didn’t. For the most part, folk laughed to see a grown man cower back from a child. In that moment my reputation for both temper and spirit were made, for before nightfall the tale of the bastard standing up to his tormentor was all over the town. Nosy scrabbled to his feet and fled with me. I had one glimpse of Cob’s face, taut with confusion as he emerged from the kitchen, pies in hands, and saw Nosy and me flee. Had he been Burrich, I probably would have halted and trusted my safety to him. But he was not, and so I ran, letting Nosy take the lead.

We fled through the trooping servants, just one more small boy and his dog racing about in the courtyard, and Nosy took me to what he obviously regarded as the safest place in the world. Far from the kitchen and the inner keep was a hollow Vixen had scraped out under a corner of a rickety outbuilding where sacks of peas and beans were stored. Here Nosy had been whelped, in total defiance of Burrich and here she had managed to keep her pups hidden for almost three days. Burrich himself had found her there. His smell was the first human smell Nosy could recall. It was a tight squeeze to get under the building, but once within, the den was warm and dry and semi-dark. Nosy huddled close to me and I put my arm around him. Hidden there, our hearts soon eased down from their wild thumpings, and from calmness we passed into the deep, dreamless sleep reserved for warm spring afternoons and puppies.

I came awake shivering, hours later. It was full dark and the tenuous warmth of the early spring day had fled. Nosy was awake as soon as I was, and together we scraped and slithered out of the den.

There was a high night sky over Buckkeep, with stars shining bright and cold. The smell of the bay was stronger as if the day-smells of men and horses and cooking were temporary things that had to surrender each night to the ocean’s power. We walked down deserted pathways, through exercise yards and past granaries and the winepress. All was still and silent. As we drew closer to the inner keep, I saw torches still burning, and heard voices still raised in talk. But it all seemed tired somehow, the last vestiges of revelry winding down before dawn came to lighten the skies. Still, we skirted the inner keep by a wide margin, having had enough of people.

I found myself following Nosy back to the stables. As we drew near the heavy doors, I wondered how we would get in. But Nosy’s tail began to wag wildly as we got closer, and then even my poor nose picked up Burrich’s scent in the dark. He rose from the wooden crate he’d been seated on by the door. ‘There you are,’ he said soothingly. ‘Come along then. Come on.’ And he stood and opened the heavy doors for us and led us in.

We followed him through darkness, between rows of stalls, past grooms and handlers put up for the night in the stables, and then past our own horses and dogs and the stable-boys who slept amongst them, and then to a staircase that climbed the wall which separated the stables from the mews. We followed Burrich up its creaking wooden treads, and then he opened another door. Dim yellow light from a guttering candle on a table blinded me temporarily. We followed Burrich into a slant-roofed chamber that smelled of Burrich and leather and the oils and salves and herbs that were part of his trade. He shut the door firmly behind us, and as he came past us to kindle a fresh candle from the nearly spent one on the table, I smelled the sweetness of wine on him.

The light spread, and Burrich seated himself on a wooden chair by the table. He looked different, dressed in fine thin cloth of brown and yellow, with a bit of silver chain across his jerkin. He put his hand out, palm up, on his knee and Nosy went to him immediately. Burrich scratched his hanging ears, and then thumped his ribs affectionately, grimacing at the dust that rose from his coat. ‘You’re a fine pair, the two of you,’ he said, speaking more to the pup than to me. ‘Look at you. Filthy as beggars. I lied to my king today for you. First time ever in my life I’ve done that. Appears as if Chivalry’s fall from grace will take me down as well. Told him you were washed up and sound asleep, exhausted from your journey. He was not pleased he would have to wait to see you, but luckily for us, he had weightier things to handle. Chivalry’s abdication has upset a lot of lords. Some are seeing it as a chance to push for an advantage, and others are disgruntled to be cheated of a king they admired. Shrewd’s trying to calm them all. He’s letting it be noised about that Verity was the one who negotiated with the Chyurda this time. Those as will believe that shouldn’t be allowed to walk about on their own. But they came, to look at Verity anew, and wonder if and when he’d be their next king, and what kind of a king he would be. Chivalry’s throwing it over and leaving for Withywood has stirred all the Duchies as if he’d poked a stick in a hive.’

Burrich lifted his eyes from Nosy’s eager face. ‘Well, fitz. Guess you got a taste of it today. Fair scared poor Cob to death, your running off like that. Now, are you hurt? Did anyone rough you up? I should have known there would be those would blame all the stir on you. Come here, then. Come on.’

When I hesitated, he moved over to a pallet of blankets made up near the fire and patted it invitingly. ‘See. There’s a place here for you, all ready. And there’s bread and meat on the table for both of you.’

His words made me aware of the covered platter on the table. Flesh, Nosy’s senses confirmed, and I was suddenly full of the smell of the meat. Burrich laughed at our rush to the table, and silently approved how I shared a portion out to Nosy before filling my own jaws. We ate to repletion, for Burrich had not under-estimated how hungry a pup and a boy would be after the day’s misadventures. And then, despite our long nap earlier, the blankets so close to the fire were suddenly immensely inviting. Bellies full, we curled up with the flames baking our backs and slept.

When we awoke the next day, the sun was well risen and Burrich already gone. Nosy and I ate the heel of last night’s loaf and gnawed the leftover bones clean before we descended from Burrich’s quarters. No one challenged us or appeared to take any notice of us.

Outside, another day of chaos and revelry had begun. The keep was, if anything, more swollen with people. Their passage stirred the dust and their mixing voices were an overlay to the shushing of the wind and the more distant muttering of the waves. Nosy drank it all in, every scent, every sight, every sound. The doubled sensory impact dizzied me. As I walked, I gathered from snatches of conversation that our arrival had coincided with some spring rite of merriment and gathering. Chivalry’s abdication was still the main topic, but it did not prevent the puppet shows and jugglers from making every corner a stage for their antics. At least one puppet show had already incorporated Chivalry’s fall from grace into its bawdy comedy, and I stood anonymous in the crowd and puzzled over dialogue about sowing the neighbour’s fields that had the adults roaring with laughter.

But very soon the crowds and the noise became oppressive to both of us, and I let Nosy know I wished to escape it all. We left the keep, passing out of the thick-walled gate past guards intent upon flirting with the merrymakers as they came and went. One more boy and dog leaving on the heels of a fish-mongering family were nothing to notice. And with no better distraction in sight, we followed the family as they wound their way down the streets away from the keep and towards the town of Buckkeep. We dropped further and further behind them as new scents demanded that Nosy investigate and then urinate at every corner, until it was just him and me wandering in the city.

Buckkeep then was a windy, raw place. The streets were steep and crooked, with paving stones that rocked and shifted out of place under the weight of passing carts. The wind blasted my inland nostrils with the scent of beached kelp and fish guts while the keening of the gulls and sea-birds were an eerie melody above the rhythmic shushing of the waves. The town clings to the rocky black cliffs much like limpets and barnacles cling to the pilings and quays that venture out into the bay. The houses were of stone and wood, with the more elaborate wooden ones built higher up the rocky face and cut more deeply into it.

Buckkeep Town was relatively quiet compared to the festivity and crowds up in the keep. Neither of us had the sense or experience to know the waterfront town was not the best place for a six-year-old and a puppy to wander. Nosy and I explored eagerly, sniffing our way down Baker’s Street and through a near-deserted market and then along the warehouses and boat-sheds that were the lowest level of the town. Here the water was close, and we walked on wooden piers as often as we did on sand and stone. Business here was going on as usual with little allowance for the carnival atmosphere up in the keep. Ships must dock and unload as the rising and falling of the tides allow, and those who fish for a living must follow the schedules of the finned creatures, not those of men.

We soon encountered children, some busy at the lesser tasks of their parents’ crafts, but some idlers like ourselves. I fell in easily with them, with little need for introductions or any of the adult pleasantries. Most of them were older than I, but several were as young or younger. None of them seemed to think it odd I should be out and about on my own. I was introduced to all the important sights of the city, including the swollen body of a cow that had washed up at the last tide. We visited a new fishing boat under construction at a dock littered with curling shavings and strong-smelling pitch spills. A fish-smoking rack left carelessly untended furnished a mid-day repast for a half-dozen of us. If the children I was with were more ragged and boisterous than those who passed at their chores, I did not notice. And had anyone told me I was passing the day with a pack of beggar brats denied entrance to the keep because of their light-fingered ways, I would have been shocked. At the time, I knew only that it was suddenly a lively and pleasant day, full of places to go and things to do.

There were a few youngsters, larger and more rambunctious, who would have taken the opportunity to set the newcomer on his ear had Nosy not been with me and showing his teeth at the first aggressive shove. But as I did not show any signs of wanting to challenge their leadership, I was allowed to follow. I was suitably impressed by all their secrets, and I would venture that by the end of the long afternoon, I knew the poorer quarter of town better than many who had grown up above it.

I was not asked for a name, but simply was called Newboy. The others had names as simple as Dick or Kerry, or as descriptive as Netpicker and Nosebleed. The last might have been a pretty little thing in better circumstances. She was a year or two older than I, but very outspoken and quick-witted. She got into one dispute with a big boy of twelve, but she showed no fear of his fists, and her sharp-tongued taunts soon had everyone laughing at him. She took her victory calmly and left me awed by her toughness. But the bruises on her face and thin arms were layered in shades of purple, blue and yellow, while a crust of dried blood below one ear belied her name. Even so, Nosebleed was a lively one, her voice shriller than the gulls that wheeled above us. Late afternoon found Kerry, Nosebleed and me on a rocky shore beyond the net-menders’ racks, with Nosebleed teaching me to scour the rocks for tight-clinging sheels. These she levered off expertly with a sharpened stick. She was showing me how to use a nail to pry the chewy inmates out of their shells when another girl hailed us with a shout.

The neat blue cloak that blew around her and the leather shoes on her feet set her apart from my companions. Nor did she come to join our harvesting, but only came close enough to call, ‘Molly, Molly, he’s looking for you, high and low. He waked up near sober an hour ago, and took to calling you names as soon as he found you gone and the fire out.’

A look mixed of defiance and fear passed over Nosebleed’s face. ‘Run away, Kittne, but take my thanks with you. I’ll remember you next time the tides bare the kelpcrabs’ beds.’

Kittne ducked her head in a brief acknowledgement and immediately turned and hastened back the way she had come.

‘Are you in trouble?’ I asked Nosebleed when she did not go back to turning over stones for sheels.

‘Trouble?’ She gave a snort of disdain. ‘That depends. If my father can stay sober long enough to find me, I might be in for a bit of it. More than likely he’ll be drunk enough tonight that not a one of whatever he hurls at me will hit. More than likely!’ she repeated firmly when Kerry opened his mouth to object to this. And with that she turned back to the rocky beach and our search for sheel.

We were crouched over a many-legged grey creature that we found stranded in a tide pool when the crunch of a heavy boot on the barnacled rocks brought all our heads up. With a shout Kerry fled down the beach, never pausing to look back. Nosy and I sprang back, Nosy crowding against me, teeth bared bravely as his tail tickled his cowardly little belly. Molly Nosebleed was either not so fast to react, or resigned to what was to come. A gangly man caught her a smack on the side of the head. He was a skinny man, red-nosed and raw-boned, so that his fist was like a knot at the end of his bony arm, but the blow was still enough to send Molly sprawling. Barnacles cut into her wind-reddened knees, and when she crabbed aside to avoid the clumsy kick he aimed at her, I winced at the salty sand that packed the new cuts.

‘Faithless little musk-cat! Didn’t I tell you to stay and tend to the dipping! And here I find you mucking about on the beach, with the tallow gone hard in the pot. They’ll be wanting more tapers up at the keep this night, and what am I to sell them?’

‘The three dozen I set this morning. That was all you left me wicking for, you drunken old sot!’ Molly got to her feet and stood bravely despite her brimming eyes. ‘What was I to do? Burn up all the fuel to keep the tallow soft so that when you finally gave me wicking we’d have no way to heat the kettle?’

The wind gusted and the man swayed shallowly against it. It brought us a whiff of him. Sweat and beer, Nosy informed me sagely. For a moment the man looked regretful, but then the pain of his sour belly and aching head hardened him. He stooped suddenly and seized a whitened branch of driftwood. ‘You won’t talk to me like that, you wild brat! Down here with the beggar boys, doing El knows what! Stealing from the smoke racks again, I’ll wager, and bringing more shame to me! Dare to run, and you’ll have it twice when I catch you.’

She must have believed him, for she only cowered as he advanced on her, putting up her thin arms to shield her head and then seeming to think better of it, and hiding only her face with her hands. I stood transfixed in horror while Nosy yelped with my terror and wet himself at my feet. I heard the swish of the driftwood knob as the club descended. My heart leaped sideways in my chest and I pushed at the man, the force jerking out oddly from my belly.

He fell, as had the keg-man the day before. But this man fell clutching at his chest, his driftwood weapon spinning harmlessly away. He dropped to the sand, gave a twitch that spasmed his whole body, and then was still.

An instant later Molly unscrewed her eyes, shrinking from the blow she still expected. She saw her father collapsed on the rocky beach, and amazement emptied her face. She leaped toward him crying, ‘Papa, Papa, are you all right? Please, don’t die, I’m sorry I’m such a wicked girl! Don’t die, I’ll be good, I promise I’ll be good.’ Heedless of her bleeding knees, she knelt beside him, turning his face so he wouldn’t breathe in sand, and then vainly trying to sit him up.

‘He was going to kill you,’ I told her, trying to make sense of the whole situation.

‘No. He hits me, a bit, when I am bad, but he’d never kill me. And when he is sober and not sick, he cries about it and begs me not to be bad and make him angry. I should take more care not to anger him. Oh, Newboy, I think he’s dead.’

I wasn’t sure myself, but in a moment he gave an awful groan and opened his eyes a bit. Whatever fit had felled him seemed to have passed. Dazedly he accepted Molly’s self-accusations and anxious help, and even my reluctant aid. He leaned on the two of us as we wove our way down the rocky beach over the uneven footing. Nosy followed us, by turns barking and racing in circles around us.

The few folk who saw us pass paid no attention to us. I guessed that the sight of Molly helping her papa home was not strange to any of them. I helped them as far as the door of a small chandlery, Molly sniffling apologies every step of the way. I left them there, and Nosy and I found our way back up the winding streets and hilly road to the keep, wondering every step at the ways of folk.

Having found the town and the beggar children once, I was drawn like a magnet to them every day afterwards. Burrich’s days were taken up with his duties, and his evenings with the drink and merriment of the Springfest. He paid little mind to my comings and goings, as long as each evening found me on my pallet before his hearth. In truth, I think he had little idea of what to do with me, other than to see that I was fed well enough to grow heartily and that I slept safe within doors at night. It could not have been a good time for him. He had been Chivalry’s man, and now that Chivalry had cast himself down, what was to become of him? That must have been much on his mind. And there was the matter of his leg. Despite his knowledge of poultices and bandaging, he could not seem to work the healing on himself that he so routinely served to his beasts. Once or twice I saw the injury unwrapped and winced at the ragged tear that refused to heal smoothly but remained swollen and oozing. Burrich cursed it roundly at first, and set his teeth grimly each night as he cleaned and re-dressed it, but as the days passed he regarded it with more of a sick despair than anything else. Eventually he did get it to close, but the ropy scar twisted his leg and disfigured his walk. Small wonder he had little mind to give to a young bastard deposited in his care.

So I ran free in the way that only small children can, unnoticed for the most part. By the time Springfest was over, the guards at the keep’s gate had become accustomed to my daily wanderings. They probably thought me an errand boy, for the keep had many of those, only slightly older than I. I learned to pilfer early from the keep’s kitchen enough for both Nosy and myself to breakfast heartily. Scavenging other food – burnt crusts from the baker’s, sheel and seaweed from the beach, smoked fish from untended racks – was a regular part of my day’s activities. Molly Nosebleed was my most frequent companion. I seldom saw her father strike her after that day; for the most part he was too drunk to find her, or to make good his threats when he did. To what I had done that day, I gave little thought, other than to be grateful that Molly had not realized I was responsible.

The town became the world to me, with the keep a place I went to sleep. It was summer, a wonderful time in a port town. No matter where I went, Buckkeep Town was alive with comings and goings. Goods came down the Buck River from the Inland Duchies, on flat river barges manned by sweating bargemen. They spoke learnedly about shoals and bars and landmarks and the rising and falling of the river waters. Their freight was hauled up into the town shops or warehouses, and then down again to the docks and into the holds of the sea ships. Those were manned by swearing sailors who sneered at the rivermen and their inland ways. They spoke of tides and storms and nights when not even the stars would show their faces to guide them. And fishermen tied up to Buckkeep docks as well, and were the most genial of the group. At least, so they were when the fish were running well.

Kerry taught me the docks and the taverns, and how a quick-footed boy might earn three or even five pence a day, running messages up the steep streets of the town. We thought ourselves sharp and daring, to thus undercut the bigger boys who asked two pence or even more for just one errand. I don’t think I have ever been as brave since as I was then. If I close my eyes, I can smell those glorious days. Oakum and tar and fresh wood shavings from the dry-docks where the shipwrights wielded their drawknives and mallets. The sweet smell of very fresh fish, and the poisonous odour of a catch held too long on a hot day. Bales of wool in the sun added their own note to the scent of oak kegs of mellow Sandsedge brandy. Sheaves of fevergone hay waiting to sweeten a forepeak mingled scents with crates of hard melons. And all of these smells were swirled by a wind off the bay, seasoned with salt and iodine. Nosy brought all he scented to my attention as his keener senses overrode my duller ones.

Kerry and I would be sent to fetch a navigator gone to say goodbye to his wife, or to bear a sampling of spices to a buyer at a shop. The harbourmaster might send us running to let a crew know some fool had tied the lines wrong and the tide was about to abandon their ship. But I liked best the errands that took us into the taverns. There the storytellers and gossips plied their trades. The storytellers told the classic tales, of voyages of discovery and crews who braved terrible storms and of foolish captains who took down their ships with all hands. I learned many of the traditional ones by heart, but the tales I loved best came not from the professional storytellers but from the sailors themselves. These were not the tales told at the hearths for all to hear, but the warnings and tidings passed from crew to crew as the men shared a bottle of brandy or a loaf of yellow pollen-bread.

They spoke of catches they’d made, nets full to sinking the boat, or of marvellous fish and beasts glimpsed only in the path of a full moon as it cut a ship’s wake. There were stories of villages raided by Outislanders, both on the coast and on the outlying islands of our duchy, the tales of pirates and battles at sea and ships taken by treachery from within. Most gripping were the tales of the Red Ship Raiders, Outislanders who both raided and pirated, and attacked not only our ships and towns but even other Outislander ships. Some scoffed at the notion of the red-keeled ships, and mocked those who told of Outislander pirates turning against others like themselves.