Полная версия:

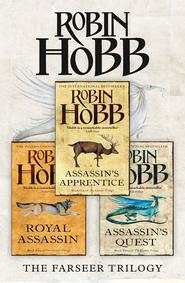

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

I had long ago stopped being surprised at what Chade knew. But this time, I was sure he did not know the real reason, and I had no desire to share it with him.

‘Have you discovered yet who tried to kill him?’

‘I haven’t … tried, really.’

Now Chade looked disgusted, and then puzzled. ‘Boy, you are not yourself at all. Six months ago you would have torn the stables apart to know such a secret. Six months ago, given a month’s holiday, you would have filled each day. What troubles you?’

I looked down, feeling the truth of his words. I wanted to tell him everything that had befallen me; I wanted not to say a word of it to anyone. ‘I’ll tell you all I do know of the attack on Burrich.’ And I did.

‘And the one who saw all this,’ he asked when I had finished. ‘Did he know the man who attacked Burrich?’

‘He didn’t get a good look at him,’ I hedged. Useless to tell Chade that I knew exactly how he smelled, but had only a vague visual image.

Chade was quiet for a moment. ‘Well, as much as you can, keep an ear to the earth. I should like to know who has grown so brave as to try to kill the King’s stablemaster in his own stable.’

‘Then you do not think it was just some personal quarrel of Burrich’s?’ I asked carefully.

‘Perhaps it was. But we will not jump to conclusions. To me, it has the feel of a gambit. Someone is building up to something, but has missed their first block. To our advantage, I hope.’

‘Can you tell me why you think so?’

‘I could, but I will not. I want to leave your mind free to find its own assumptions, independent of mine. Now come. I will show you the teas.’

I was more than a bit hurt that he asked me nothing about my time with Galen or my test. He seemed to accept my failure as a thing expected. But as he showed me the ingredients he had chosen for Verity’s teas, I was horrified by the strength of the stimulants he was using.

I had seen little of Verity, though Regal had been in only too much evidence. He had spent the last month coming and going, always just returning, or just leaving, and each cavalcade seemed richer and more ornate than the one before. It seemed to me that he was using the excuse of his brother’s courting to feather himself more brightly than any peacock. Common opinion was that he must go so, to impress those with whom he negotiated. For myself, I saw it as a waste of coin that could have gone on defences. When Regal was gone, I felt relief, for his antagonism toward me had taken a recent bound, and he had found sundry small ways to express it.

The brief times when I had seen Verity or the King, they had both looked harassed and worn. But Verity especially had seemed almost stunned. Impassive and distracted, he had noticed me only once, and then smiled wearily and said I had grown. That had been the extent of our conversation. But I had noticed that he ate like an invalid, without appetite, eschewing meat and bread as if they were too great an effort to chew and swallow, instead subsisting on porridges and soups.

‘He is using the Skill too much. That much Shrewd has told me. But why it should drain him so, why it should burn the very flesh from his bones, he cannot explain to me. So I give him tonics and elixirs, and try to get him to rest. But he cannot. He dares not, he says. He tells me that all his efforts are necessary to delude the Red Ship navigators, to send their ships onto the rocks, to discourage their captains. And so he rises from bed, and goes to his chair by a window, and there he sits, all the day.’

‘And Galen’s coterie? Are they of no use to him?’ I asked the question almost jealously, almost hoping to hear they were of no consequence.

Chade sighed. ‘I think he uses them as I would use carrierpigeons. He has sent them out to the towers, and he uses them to convey warnings to his soldiers, and to receive from them sightings of ships. But the task of defending the coast he trusts to no one else. Others, he tells me, would be too inexperienced; they might betray themselves to those they Skilled. I do not understand. But I know he cannot continue much longer. I pray for the end of summer, for winter storms to blow the Red Ships home. Would there were someone to spell him at this work. I fear it will consume him.’

I took that as a rebuke for my failure and subsided into a sulky silence. I drifted around his chambers, finding them both familiar and strange after my months of absence. The apparatus for his herbal work was, as always, cluttered about. Slink was very much in evidence, with his smelly bits of bones in corners. As always, there was an assortment of tablets and scrolls by various chairs. This crop seemed to deal mostly with Elderlings. I wandered about, intrigued by the coloured illustrations. One tablet, older and more elaborate than the rest, depicted an Elderling as a sort of gilded bird with a man-like head crowned with quillish hair. I began to piece out the words. It was in Piche, an ancient native tongue of Chalced, the southernmost duchy. Many of the painted symbols had faded, or flaked away from the old wood, and I had never been fluent in Piche. Chade came to stand at my elbow.

‘You know,’ he said gently. ‘It was not easy for me, but I kept my word. Galen demanded complete control of his students. He expressly stipulated that no one might contact you or interfere in any way with your discipline and instruction. And, as I told you, in the Queen’s Garden, I am blind and without influence.’

‘I knew that,’ I muttered.

‘Yet I did not disagree with Burrich’s actions. Only my word to my king kept me from contacting you.’ He paused cautiously. ‘It has been a difficult time, I know. I wish I could have helped you. And you should not feel too badly that you –’

‘Failed.’ I filled in the word while he searched for a gentler one. I sighed, and suddenly admitted my pain. ‘Let’s leave it, Chade. I can’t change it.’

‘I know.’ Then, even more carefully, ‘But perhaps we can use what you learned of the Skill. If you can help me understand it, perhaps I can devise better ways to spare Verity. For so many years, the knowledge has been kept too secret … there is scarcely a mention of it in the old scrolls, save to say that such and such a battle was turned by the King’s Skill upon his soldiers, or such and such an enemy was confounded by the King’s Skill. Yet there is nothing of how it is done, or …’

Despair closed its grip on me again. ‘Leave it. It is not for bastards to know. I think I’ve proved that.’

A silence fell between us. At last Chade sighed heavily. ‘Well. That’s as may be. I’ve been looking into Forging as well, over these last few months. But all I’ve learned of it is what it is not, and what does not work to change it. The only cure I’ve found for it is the oldest one known to work on anything.’

I rolled and fastened the scroll I had been looking at, feeling I knew what was coming. I was not mistaken.

‘The King has charged me with an assignment for you.’

That summer, over three months, I killed seventeen times for the King. Had I not already killed, out of my own volition and defence, it might have been harder.

The assignments might have seemed simple. Me, a horse, and panniers of poisoned bread. I rode roads where travellers had reported being attacked, and when the Forged ones attacked me, I fled, leaving a trail of spilled loaves. Perhaps if I had been an ordinary man-at-arms, I would have been less frightened. But all my life I had been accustomed to relying on my Wit to let me know when others were about. To me, it was tantamount to having to work without using my eyes. And I swiftly found out that not all Forged ones had been cobblers and weavers. The second little clan of them that I poisoned had several soldiers among them. I was fortunate that most of them were squabbling over loaves when I was dragged from my horse. I took a deep cut from a knife, and to this day I bear the scar on my left shoulder. They were strong and competent, and seemed to fight as a unit, perhaps because that was how they had been drilled, back when they were fully human. I would have died, except that I cried out to them that it was foolish to struggle with me while the others were eating all the bread. They dropped me, I struggled to my horse, and escaped.

The poisons were no crueller than they had to be, but to be effective even in the smallest dosage, we had to use harsh ones. The Forged ones did not die gently, but it was as swift a death as Chade could concoct. They snatched their deaths from me eagerly, and I did not have to witness their frothing convulsions, or even see their bodies by the road. When news of the fallen Forged ones reached Buckkeep, Chade’s tale that they had probably died from eating spoiled fish from spawning streams had already spread as a ubiquitous rumour. Relatives collected the bodies and gave them proper burial. I told myself that they were probably relieved, and that the Forged ones had met a quicker end than if they had starved to death over winter. And so I became accustomed to killing, and had nearly a score of deaths to my credit before I had to meet the eyes of a man, and then kill him.

That one, too, was not so difficult as it might have been. He was a minor lordling, holding lands outside Turlake. A story reached Buckkeep that he had, in a temper, struck the child of a servant, and left the girl a witling. That was sufficient to raise King Shrewd’s lip. But the lordling had paid the full blood-debt, and by accepting it the servant had given up any form of the King’s justice. But some months later there came to court a cousin of the girl’s, and she petitioned for private audience with Shrewd.

I was sent to confirm her tale, and saw how the girl was kept like a dog at the foot of the lordling’s chair, and more, how her belly had begun to swell with child. And so it was not too difficult, as he offered me wine in fine crystal and begged the latest news of the King’s Court at Buckkeep, for me to find a time to lift his glass to the light and praise the quality of both vessel and wine. I left some days later, my errand completed, with the samples of paper I had promised Fedwren, and the conveyed wishes of the lordling for a good trip home. The lordling was indisposed that day. He died, in blood and madness and froth, a month or so later. The cousin took in both girl and child. To this day, I have no regrets, for the deed or for the choice of slow death for him.

And when I was not dealing death to Forged ones, I waited on my lord Prince Verity. I remember the first time I climbed all those stairs to his tower, balancing a tray as I went. I had expected a guard or sentry at the top. There was none. I tapped at the door, and receiving no answer, entered quietly. Verity was sitting in a chair by a window. A summer wind off the ocean blew into the room. It could have been a pleasant chamber, full of light and air on a stuffy summer day. Instead it seemed to me a cell. There was the chair by the window, and a small table next to it. In the corners and around the edges of the room the floor was dusty and littered with bits of old strewing-reeds. And Verity, chin slumped to his chest as if dozing, except that to my senses the room thrummed with his effort. His hair was unkempt, his chin bewhiskered with a day’s growth. His clothing hung on him.

I pushed the door shut with my foot and took the tray to the table. I set it down and stood beside it, quietly waiting. And in a few minutes he came back from wherever he had been. He looked up at me with a ghost of his old smile, and then down at his tray. ‘What’s this?’

‘Breakfast, sir. Everyone else ate hours ago, save yourself.’

‘I ate, boy. Early this morning. Some awful fish soup. The cooks should be hung for that. No one should face fish first thing in the morning.’ He seemed uncertain, like some doddering gaffer trying to recall the days of his youth.

‘That was yesterday, sir.’ I uncovered the plates. Warm bread swirled with honey and raisins, cold meats, a dish of strawberries and a small pot of cream for them. All were small portions, almost a child’s serving. I poured the steaming tea into a waiting mug. It was flavoured heavily with ginger and peppermint, to cover the ground elfbark’s tang.

Verity glanced at it, and then up to me. ‘Chade never relents, does he?’ Spoken so casually, as if Chade’s name were mentioned everyday about the keep.

‘You need to eat, if you are to continue,’ I said neutrally.

‘I suppose so,’ he said wearily, and turned to the tray as if the artfully-arranged food were yet another duty to attend to. He ate with no relish for the food, and drank the tea in a manful draught, as a medicine, undeceived by ginger or mint. Halfway through the meal he paused with a sigh, and gazed out of the window for a bit. Then, seeming to come back again, he forced himself to consume each item completely. He pushed the tray aside, and leaned back in the chair as if exhausted. I stared. I had prepared the tea myself. That much elfbark would have had Sooty leaping over the stall walls.

‘My prince?’ I said, and when he did not stir, I touched his shoulder lightly. ‘Verity? Are you all right?’

‘Verity,’ he repeated as in a daze. ‘Yes. And I prefer that to “sir” or “my prince” or “my lord”. This is my father’s gambit, to send you. Well. I may surprise him yet. But, yes, call me Verity. And tell them I ate. Obedient as ever, I ate. Go on, now, boy. I have work to do.’

He seemed to roust himself with an effort, and once more his gaze went afar. I stacked the dishes as quietly as I could onto the tray and headed toward the door. But as I lifted the latch, he spoke again.

‘Boy?’

‘Sir?’

‘Ah-ah!’ he warned me.

‘Verity?’

‘Leon is in my rooms, boy. Take him out for me, will you? He pines. There is no sense in the both of us shrivelling like this.’

‘Yes, sir. Verity.’

And so the old hound, past his prime now, came to be in my care. Each day I took him from Verity’s room, and we hunted the back hills and cliffs and the beaches for wolves that had not run there in a score of years. As Chade had suspected, I was badly out of condition, and at first it was all I could do to keep up even with the old hound. But as the days went by, we regained our tone, and Leon even caught a rabbit or two for me. Now that I was exiled from Burrich’s domain, I did not scruple to use the Wit whenever I wished. But as I had discovered long ago, I could communicate with Leon, but there was no bond. He did not always heed me, nor even believe me all the time. Had he been but a pup, I am sure we could have bonded to one another. But he was old, and his heart given forever to Verity. The Wit was not dominion over beasts, but only a glimpse into their lives.

And thrice a day I climbed the steeply winding steps, to coax Verity to eat, and to a few words of conversation. Some days it was like speaking to a child or a doddering oldster. On others, he asked after Leon, and quizzed me about matters down in Buckkeep Town. Sometimes I was absent for days on my other assignments. Usually, he seemed not to have noticed, but once, after the foray in which I took my knife wound, he watched me awkwardly load his empty dishes onto the tray. ‘How they must laugh in their beards, if they knew we slay our own.’

I froze, wondering what answer to make to that, for as far as I knew, my tasks were known only to Shrewd and Chade. But Verity’s eyes had gone afar again, and I left silently.

Without intending to, I began to make changes around him. One day, while he was eating, I swept the room, and later that evening brought up a sackful of strewing-reeds and herbs. I had worried that I might be a distraction to him, but Chade had taught me to move quietly. I worked without speaking, and Verity acknowledged neither my coming nor going. But the room was freshened, and the ververia blossoms mixed in with the strewing herbs were an enlivening herb. Coming in once, I discovered him dozing in his hard-backed chair. I brought up cushions, which he ignored for several days, and then one day had arranged to his liking. The room remained bare, but I sensed he needed it so, to preserve his single-mindedness. So what I brought him were the barest items of comfort, no tapestries or wall hangings, no vases of flowers or tinkling wind chimes, but flowering thymes in pots to ease the headaches that plagued him, and on one stormy day, a blanket against the rain and chill from the open window.

On that day I found him sleeping in his chair, limp as a dead thing. I tucked the blanket around him as if he were an invalid, and set the tray before him, but left it covered, to keep the good heat in the food. I sat down on the floor next to his chair, propped against one of his discarded cushions, and listened to the silence of the room. It seemed almost peaceful today, despite the driving summer rain outside the open window, and the gale wind that gusted in from time to time. I must have dozed, for I woke to his hand on my hair.

‘Do they tell you to watch over me so, boy, even when I sleep? What do they fear, then?’

‘Naught that I know, Verity. They tell me only to bring you food, and see as best I can that you eat it. No more than that.’

‘And blankets and cushions, and pots of sweet flowers?’

‘My own doing, my prince. No man should live in such a desert as this.’ And in that moment, I realized we were not speaking aloud, and sat bolt upright and looked at him.

Verity, too, seemed to come to himself. He shifted in his comfortless chair. ‘I bless this storm, that lets me rest. I hid it from three of their ships, persuading those who looked to the sky that it was no more than a summer squall. Now they ply their oars and peer through the rain, trying to keep their courses. And I can snatch a few moments of honest sleep.’ He paused. ‘I ask your pardon, boy. Sometimes, now, the Skilling seems more natural than speaking. I did not mean to intrude on you.’

‘No matter, my prince. I was but startled. I cannot Skill myself, except weakly and erratically. I do not know how I opened to you.’

‘Verity, boy, not your prince. No one’s prince sits still in a sweaty shirt, with two days of beard. But what is this nonsense? Surely it was arranged for you to learn the Skill? I remember well how Patience’s tongue battered away my father’s resolve.’ He permitted himself a weary smile.

‘Galen tried to teach me, but I had not the aptitude. With bastards, I am told it is often …’

‘Wait,’ he growled, and in an instant was within my mind. ‘This is faster,’ he offered, by way of apology, and then, muttering to himself, ‘What is this, that clouds you so? Ah!’ and was gone again from my mind, and all as deft and easy as Burrich taking a tick off a hound’s ear. He sat long, quiet, and so did I, wondering.

‘I am strong in it, as was your father. Galen is not.’

‘Then how did he become Skillmaster?’ I asked quietly. I wondered if Verity were saying this only to somehow make me feel my failure less.

Verity paused as if skirting a delicate subject. ‘Galen was Queen Desire’s … pet. A favourite. The Queen emphatically suggested Galen as apprentice to Solicity. Often I think our old Skillmaster was desperate when she took him as apprentice. Solicity knew she was dying, you see. I believe she acted in haste, and towards the end, regretted her decision. And I do not think he had half the training he should have had before becoming “master”. But there he is; he is what we have.’

Verity cleared his throat and looked uncomfortable. ‘I will speak as plainly as I can, boy, for I see that you know how to hold your tongue when it is wise. Galen was given that place as a plum, not because he merited it. I do not think he has ever fully grasped what it means to be the Skillmaster. Oh, he knows the position carries power, and he has not scrupled to wield it. But Solicity was more than someone who swaggered about secure in a high position. Solicity was advisor to Bounty, and a link between the King and all who Skilled for him. She made it her business to seek out and teach as many as manifested real talent and the judgement to use it well. This coterie is the first group Galen has trained since Chivalry and I were boys. And I do not find them well-taught. No, they are trained, as monkeys and parrots are taught to mimic men, with no understanding of what they do. But they are what I have.’ Verity looked out of the window and spoke softly. ‘Galen has no finesse. He is as coarse as his mother was, and just as presumptuous.’ Verity paused suddenly, and his cheeks flushed as if he had said something ill-considered. He resumed more quietly. ‘The Skill is like language, boy. I need not shout at you to let you know what I want. I can ask politely, or hint, or let you know my wish with a nod and a smile. I can Skill a man, and leave him thinking it was all his own idea to please me. But all that eludes Galen, both in the use of the Skill and the teaching of it. Privation and pain are one way to lower a man’s defences; it is the only way Galen believes in. But Solicity used guile. She would have me watch a kite, or a bit of dust floating in a sunbeam, focusing on it as if there were nothing else in the world. And suddenly, there she would be, inside my mind with me, smiling and praising me. She taught me that being open was simply not being closed. And going into another’s mind is mostly done by being willing to go outside of your own. Do you see, boy?’

‘Somewhat,’ I hedged.

‘Somewhat,’ he sighed. ‘I could teach you to Skill, had I but the time. I do not. But tell me this: were your lessons going well, before he tested you?’

‘No. I never had any aptitude … wait! That’s not true! What am I saying, what have I been thinking?’ Though I was sitting, I swayed suddenly, my head bounding off the arm of Verity’s chair. He reached out a hand and steadied me.

‘I was too swift, I suppose. Steady now, boy. Someone had misted you. Befuddled you, much as I do Red Ship navigators and steersmen. Convince them they’ve taken a sighting already and their course is true when really they are steering into a cross-current. Convince them they’ve passed a point they haven’t sighted yet. Someone convinced you that you could not Skill.’

‘Galen.’ I spoke with certainty. I almost knew the moment. He had slammed into me that afternoon, and from that time, nothing had been the same. I had been living in a fog, all those months …

‘Probably. Though if you Skilled into him at all, I’m sure you’ve seen what Chivalry did to him. He hated your father with a passion, prior to Chiv turning him into a lapdog. We felt badly about it. We’d have undone it, if we could have worked out how to do it, and escape Solicity’s detection. But Chiv was strong with the Skill, and we were all but boys then, and Chiv was angry when he did it. Over something Galen had done to me, ironically. Even when Chivalry was not angry, being Skilled by him was like being trampled by a horse. Or ducked in a fast-flowing river, more like. He’d get in a hurry, barge into you, dump his information and flee.’ He paused again, and reached to uncover a dish of soup on his tray. ‘I suppose I’ve always assumed you knew all this. Though I’m damned if there’s any way you could have. Who would have told you?’

I seized on one piece of information. ‘You could teach me to Skill?’

‘If I had time. A great deal of time. You’re a lot like Chiv and I were, when we learned. Erratic. Strong, but with no idea of how to bring that strength to bear. And Galen has … well, scarred you, I suppose. You’ve walls I can’t begin to penetrate, and I am strong. You’d have to learn to drop them. That’s a hard thing. But I could teach you, yes. If you and I had a year, and nothing else to do.’ He pushed the soup aside. ‘But we don’t.’

My hopes crashed again. This second wave of disappointment engulfed me, grinding me against stones of frustration. My memories all re-ordered themselves, and in a surge of anger, I knew all that had been done to me. Were it not for Smithy, I’d have dashed my life out at the base of the tower that night. Galen had tried to kill me, just as surely as if he’d had a knife. No one would even have known of how he’d beaten me, save his loyal coterie. And while he’d failed at that, he had taken from me the chance to learn Skilling. He’d crippled me, and I would … I leaped to my feet, furious.