Полная версия:

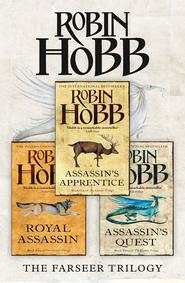

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

‘One thing,’ I said, and ignored his scowl at the delay. ‘I have to ask this, Chade. Were you here because you didn’t trust me?’

‘A fair question, I suppose. No. I was here to listen in the town, to women’s talk, as you were to listen in the keep. Bonnet-makers and button-sellers may know more than a high king’s advisor, without even knowing they know it. Now. Do we ride?’

We did. We left by the side entrance, and the bay was tethered right outside. Sooty didn’t much care for him, but she minded her manners. I sensed Chade’s impatience, but he kept the horses to an easy pace until we had left the cobbled streets of Neatbay behind us. Once the lights of the houses were behind us, we put our horses to an easy canter. Chade led, and I wondered at how well he rode, and how effortlessly he selected paths in the dark. Sooty did not like this swift travelling by night. If it had not been for a moon nearly at the full, I don’t think I could have persuaded her to keep up with the bay.

I will never forget that night ride. Not because it was a wild gallop to the rescue, but because it was not. Chade guided us and used the horses as if they were game-pieces on a board. He did not play swiftly, but to win. And so there were times when we walked the horses to breathe them, and places on the trail where we dismounted and led them to get them safely past treacherous places.

As morning greyed the sky, we stopped to eat provisions from Chade’s saddlebags. We were on a hilltop so thickly treed that the sky was barely glimpsed overhead. I could hear the ocean, and smell it, but could catch no sight of it. Our trail had become a sinuous path, little more than a deer-run, through these woods. Now that we were still, I could hear and smell the life all around us. Birds called, and I heard the movement of small animals in the underbrush and in the branches overhead. Chade had stretched, then sunk down to sit on deep moss with his back against a tree. He drank deeply from a water-skin, and then more briefly from a brandy flask. He looked tired, and the daylight exposed his age more cruelly than lamplight ever had. I wondered if he would last through the ride or collapse.

‘I’ll be fine,’ he said when he caught me watching him. ‘I’ve had to do more arduous duty than this, and on less sleep. Besides, we’ll have a good five or six hours of rest on the boat, if the crossing is smooth. So there’s no need to be longing after sleep. Let’s go, boy.’

About two hours later our path diverged, and again we took the more obscure branching. Before long I was all but lying on Sooty’s neck to escape the low sweeps of the branches. It was muggy under the trees and we were blessed with multitudes of tiny stinging flies that tortured the horses and crept into my clothes to find flesh to feast on. So thick were they that when I finally mustered the courage to ask Chade if we had gone astray, I near choked on the ones that rushed into my mouth.

By midday we emerged onto a windswept hillside that was more open. Once more I saw the ocean. The wind cooled the sweating horses and swept the insects away. It was a great pleasure simply to sit upright in the saddle again. The trail was wide enough that I could ride abreast of Chade. The livid spots stood out starkly against his pale skin; he looked more bloodless than the Fool. Dark circles underscored his eyes. He caught me watching him and frowned.

‘Report to me, instead of staring at me like a simpleton,’ he ordered me tersely, and so I did.

It was hard to watch the trail and his face at the same time, but the second time he snorted, I glanced over at him to find wry amusement on his face. I finished my report and he shook his head.

‘Luck. Same luck your father had. Your kitchen-diplomacy may be enough to turn the situation around; if that is all there is to it. The little gossip I heard agreed. Well. Kelvar was a good duke before this, and it sounds as if all that happened was a young bride going to his head.’ He sighed suddenly. ‘Still, it’s bad, with Verity there to rebuke a man for not minding his towers, and Verity himself with a raid on a Buckkeep town. Damn! There’s so much we don’t know. How did the Raiders get past our towers without being spotted? How did they know that Verity was away from Buckkeep at Neatbay? Or did they know? Was it luck for them? And what does that strange ultimatum mean? Is it a threat, or a mockery?’ For a moment we rode silently.

‘I wish I knew what action Shrewd was taking. When he sent me the messenger, he had not yet decided. We may get to Forge to find that all’s been settled already. And I wish I knew exactly what message he Skilled to Verity. They say that in the old days, when more men trained in the Skill, a man could tell what his leader was thinking about just by being silent and listening for a while. But that may be no more than a legend. Not many are taught the Skill, any more. I think it was King Bounty who decided that. Keep the Skill more secret, more of an elite tool, and it becomes more valuable. That was the logic then. I never much understood it. What if they said that of good bowmen, or navigators? Still, I suppose the aura of mystery might give a leader more status with his men … or for a man like Shrewd, now, he’d enjoy having his underlings wondering if he can actually pick up what they were thinking without their uttering a word. Yes, that would appeal to Shrewd, that would.’

At first I thought Chade was very worried, or even angry. I had never heard him ramble so on a topic. But when his horse shied over a squirrel crossing his path, Chade was very nearly unseated. I reached out and caught at his reins. ‘Are you all right? What’s the matter?’

He shook his head slowly. ‘Nothing. When we get to the boat, I’ll be all right. We just have to keep going. It’s not much farther now.’ His pale skin had become grey, and with every step his horse took, he swayed in his saddle.

‘Let’s rest a bit,’ I suggested.

‘Tides won’t wait. And rest wouldn’t help me, not the rest I’d get while I was worrying about our boat going on the rocks. No. We just have to keep going.’ And he added, ‘Trust me, boy. I know what I can do, and I’m not so foolish as to attempt more than that.’

And so we went on. There was very little else we could do. But I rode beside his horse’s head, where I could take his reins if I needed to. The sound of the ocean grew louder, and the trail much steeper. Soon I was leading the way whether I would or no.

We broke clear of brush completely on a bluff overlooking a sandy beach.

‘Thank Eda, they’re here,’ Chade muttered behind me, and then I saw the shallow-draught boat that was all but grounded near the point. A man on watch hallooed and waved his cap in the air. I lifted my arm in return greeting.

We made our way down, sliding more than riding, and then Chade boarded immediately. That left me with the horses. Neither was anxious to enter the waves, let alone heave themselves over the low rail and up onto deck. I tried to quest toward them, to let them know what I wanted. For the first time in my life, I found I was simply too tired. I could not find the focus I needed. So three deckhands, much cursing, and two duckings for me were required finally to get them loaded. Every bit of leather and every buckle on their harness had been doused with saltwater. How was I going to explain that to Burrich? That was the thought that was uppermost in my mind as I settled myself in the bow and watched the rowers in the dory bend their backs to the oars and tow us out to deeper water.

TEN

The Pocked Man

Time and tide wait for no man. There’s an ageless adage. Sailors and fishermen mean it simply to say that a boat’s schedule is determined by the ocean, not man’s convenience. But sometimes I lie here, after the tea has calmed the worst of the pain, and wonder about it. Tides wait for no man, and that I know is true. But time? Did the times I was born into await my birth to be? Did the events rumble into place like the great wooden gears of the clock of Sayntanns, meshing with my conception and pushing my life along? I make no claim to greatness. And yet, had I not been born, had not my parents fallen before a surge of lust, so much would be different. So much. Better? I think not. And then I blink and try to focus my eyes, and wonder if these thoughts come from me or from the drug in my blood. It would be nice to hold council with Chade, one last time.

The sun had moved round to late afternoon when someone nudged me awake. ‘Your master wants you,’ was all he said, and I roused with a start. Gulls wheeling overhead, fresh sea air and the dignified waddle of the boat recalled me to where I was. I scrambled to my feet, ashamed to have fallen asleep without even wondering if Chade were comfortable. I hurried aft to the ship’s house.

There I found Chade had taken over the tiny galley table. He was poring over a map spread out on it, but a large tureen of fish chowder was what got my attention. He motioned me to it without taking his attention from the map, and I was glad to fall to. There were ship’s biscuits to go with it, and a sour red wine. I had not realized how hungry I was until the food was before me. I was scraping my dish with a bit of biscuit when Chade asked me, ‘Better?’

‘Much,’ I said. ‘How about you?’

‘Better,’ he said, and looked at me with his familiar hawk’s glance. To my relief, he seemed totally recovered. He pushed my dishes to one side and slid the map before me. ‘By evening,’ he said, ‘we’ll be here. It’ll be a nastier landing than the loading was. If we’re lucky, we’ll get wind when we need it. If not, we’ll miss the best of the tide, and the current will be stronger. We may end up swimming the horses to shore while we ride in the dory. I hope not, but be prepared for it, just in case. Once we land …’

‘You smell of carris seed.’ I said it, not believing my own words. But I had caught the unmistakable sweet taint of the seed and oil on his breath. I’d had carris seed cakes, at Springfest, when everyone does, and I knew the giddy energy that even a sprinkling of the seed on a cake’s top could bring. Everyone celebrated Spring’s Edge that way. Once a year, what could it hurt? But I knew, too, that Burrich had warned me never to buy a horse that smelled of carris seed at all. And warned me further that if anyone were ever caught putting carris seed oil on any of our horse’s grain, he’d kill him. With his bare hands.

‘Do I? Fancy that. Now, I suggest that if you have to swim the horses, you put your shirt and cloak into an oilskin bag and give it to me in the dory. That way you’ll have at least that much dry to put on when we reach the beach. From the beach, our road will …’

‘Burrich says that once you’ve given it to an animal, it’s never the same. It does things to horses. He says you can use it to win one race, or run down one stag, but after that, the beast will never be what it was. He says dishonest horse-traders use it to make an animal show well at a sale; it gives them spirit and brightens their eyes, but that soon passes. Burrich says that it takes away all their sense of when they’re tired, so they go on, past the time when they should have dropped from exhaustion. Burrich told me that sometimes when the carris oil wears out, the horse just drops in its tracks.’ The words spilled out of me, cold water over stones.

Chade lifted his gaze from the map. He stared at me mildly. ‘Fancy Burrich knowing all that about carris seed. I’m glad you listened to him so closely. Now perhaps you’ll be so kind as to give me equal attention as we plan the next stage of our journey.’

‘But Chade …’

He transfixed me with his eyes. ‘Burrich is a fine horse-master. Even as a boy he showed great promise. He is seldom wrong … when speaking about horses. Now attend to what I am saying. We’ll need a lantern to get from the beach to the cliffs above. The path is very bad; we may need to bring one horse up at a time. But I am told it can be done. From there, we go overland to Forge. There isn’t a road that will take us there quickly enough to be of any use. It’s hilly country, but not forested. And we’ll be going by night, so the stars will have to be our map. I am hoping to reach Forge by mid-afternoon. We’ll go in as travellers, you and I. That’s all I’ve decided so far; the rest will have to be planned from hour to hour …’

And the moment in which I could have asked him how he could use the seed and not die of it was gone, shouldered aside by his careful plans and precise details. For half an hour more he lectured me on details, and then he sent me from the cabin, saying he had other preparations to make and that I should check on the horses and get what rest I could.

The horses were forward, in a makeshift rope enclosure on deck. Straw cushioned the deck from their hooves and droppings. A sour-faced mate was mending a bit of railing that Sooty had kicked loose in the boarding. He didn’t seem disposed to talk, and the horses were as calm and comfortable as could be expected. I roved the deck briefly. We were on a tidy little craft, an inter-island trader wider than she was deep. Her shallow draught let her go up rivers or right onto beaches without damage, but her passage over deeper water left a lot to be desired. She sidled along, with here a dip and there a curtsey, like a bundle-laden farm-wife making her way through a crowded market. We seemed to be the sole cargo. A deckhand gave me a couple of apples to share with the horses, but little talk. So after I had parcelled out the fruit, I settled myself near them on their straw and took Chade’s advice about resting.

The winds were kind to us, and the captain took us in closer to the looming cliffs than I’d have thought possible, but unloading the horses from the vessel was still an unpleasant task. All of Chade’s lecturing and warnings had not prepared me for the blackness of night on the water. The lanterns on the deck seemed pathetic efforts, confusing me more with the shadows they threw than aiding me with their feeble light. In the end, a deckhand rowed Chade to shore in the ship’s dory. I went overboard with the reluctant horses, for I knew Sooty would fight a lead rope and probably swamp the dory. I clung to Sooty and encouraged her, trusting her common sense to take us toward the dim lantern on shore. I had a long line on Chade’s horse, for I didn’t want his thrashing too close to us in the water. The sea was cold, the night was black, and if I’d had any sense, I’d have wished myself elsewhere; but there is something in a boy that takes the mundanely difficult and unpleasant and turns it into a personal challenge and an adventure.

I came out of the water dripping, chilled and completely exhilarated. I kept Sooty’s reins and coaxed Chade’s horse in. By the time I had them both under control, Chade was beside me, lantern in hand, laughing exultantly. The dory man was already away and pulling for the ship. Chade gave me my dry things, but they did little good pulled on over my dripping clothes. ‘Where’s the path?’ I asked, my voice shaking with my shivering.

Chade gave a derisive snort. ‘Path? I had a quick look while you were pulling in my horse. It’s no path, it’s no more than the course the water takes when it runs off down the cliffs. But it will have to do.’

It was a little better than he had reported, but not much. It was narrow and steep and the gravel on it was loose underfoot. Chade went ahead with the lantern. I followed, with the horses in tandem. At one point Chade’s bay acted up, tugging back, throwing me off-balance and nearly driving Sooty to her knees in her efforts to go the other direction. My heart was in my mouth until we reached the top of the cliffs.

Then the night and the open hillside spread out before us under the sailing moon and the stars scattered wide overhead, and the spirit of the challenge caught me up again. I suppose it could have been Chade’s attitude. The carris seed made his eyes wide and bright, even by lantern light, and his energy, unnatural though it was, was infectious. Even the horses seemed affected, snorting and tossing their heads. Chade and I laughed dementedly as we adjusted harness and then mounted. Chade glanced up to the stars, and then around the hillside that sloped down before us. With careless disdain he tossed our lantern to one side.

‘Away!’ he announced to the night, and kicked the bay, who sprang forward. Sooty was not to be outdone, and so I did as I had never dared before, galloping down unfamiliar terrain by night. It is a wonder we did not all break our necks. But there it is; sometimes luck belongs to children and madmen. That night I felt we were both.

Chade led and I followed. That night, I grasped another piece of the puzzle that Burrich had always been to me. For there is a very strange peace in giving over your judgement to someone else, to saying to them, ‘You lead and I will follow, and I will trust entirely that you will not lead me to death or harm.’ That night, as we pushed the horses hard, and Chade steered us solely by the night sky, I gave no thought to what might befall us if we went astray from our bearing, or if a horse were injured by an unexpected slip. I felt no sense of accountability for my actions. Suddenly, everything was easy and clear. I simply did whatever Chade told me to do, and trusted to him to have it turn out right. My spirit rode high on the crest of that wave of faith, and sometime during the night it occurred to me: this was what Burrich had had from Chivalry, and what he missed so badly.

We rode the entire night. Chade breathed the horses, but not as often as Burrich would have. And he stopped more than once to scan the night sky and then the horizon to be sure our course was true. ‘See that hill there, against the stars? You can’t see it too well, but I know it. By light, it’s shaped like a buttermonger’s cap. Keeffashaw, it’s called. We keep it to the west of us. Let’s go.’

Another time he paused on a hilltop. I pulled in my horse beside his. Chade sat still, very tall and straight. He could have been carved of stone. Then he lifted an arm and pointed. His hand shook slightly. ‘See that ravine down there? We’ve come a bit too far to the east. We’ll have to correct as we go.’

The ravine was invisible to me, a darker slash in the dimness of the starlit landscape. I wondered how he could have known it was there. It was perhaps half an hour later that he gestured off to our left, where on a rise of land a single light twinkled. ‘Someone’s up tonight in Woolcot,’ he observed. ‘Probably the baker, putting early-morning rolls to rise.’ He half-turned in his saddle and I felt more than saw his smile. ‘I was born less than a mile from here. Come, boy, let’s ride. I don’t like to think of Raiders so close to Woolcot.’

And on we went, down a hillside so steep that I felt Sooty’s muscles bunch as she leaned back on her haunches and more than half-slid her way down.

Dawn was greying the sky before I smelled the sea again. And it was still early when we crested a rise and looked down on the little village of Forge. It was a poor place in some ways; the anchorage was good only on certain tides. The rest of the time the ships had to anchor further out and let small craft ply back and forth between them and shore. About all that Forge had to keep it on the map was iron ore. I had not expected to see a bustling city. But neither was I prepared for the rising tendrils of smoke from blackened, open-roofed buildings. Somewhere an unmilked cow was lowing. A few scuttled boats were just off the shore, their masts sticking up like dead trees.

Morning looked down on empty streets. ‘Where are the people?’ I wondered aloud.

‘Dead, taken hostage, or hiding in the woods still.’ There was a tightness in Chade’s voice that drew my eyes to his face. I was amazed at the pain I saw there. He saw me staring at him and shrugged mutely. ‘The feeling that these folk belong to you, that their disaster is your failure … it will come to you as you grow. It goes with the blood.’ He left me to ponder that as he nudged his weary mount into a walk. We threaded our way down the hill and into the town.

Going more slowly seemed to be the only caution Chade was taking. There were two of us, weaponless, on tired horses, riding into a town where …

‘The ship’s gone, boy. A raiding ship doesn’t move without a full complement of rowers. Not in the current off this piece of coast. Which is another wonder. How did they know our tides and currents well enough to raid here? Why raid here at all? To carry off iron ore? Easier by far for them to pirate it off a trading-ship. It doesn’t make sense, boy. No sense at all.’

Dew had settled heavily the night before. There was a rising stench in the town, of burned, wet homes. Here and there a few still smouldered. In front of some, possessions were strewn out into the street, but I did not know if the inhabitants had tried to save some of their goods, or if the Raiders had begun to carry things off and then changed their minds. A salt-box without a lid, several yards of green woollen goods, a shoe, a broken chair: the litter spoke mutely but eloquently of all that was homely and safe broken forever and trampled in the mud. A grim horror settled on me.

‘We’re too late,’ Chade said softly. He reined his horse in and Sooty stopped beside him.

‘What?’ I asked stupidly, jolted from my thoughts.

‘The hostages. They returned them.’

‘Where?’

Chade looked at me incredulously, as if I were insane or very stupid. ‘There. In the ruins of that building.’

It is difficult to explain what happened to me in the next moment of my life. So much occurred, all at once. I lifted my eyes to see a group of people, all ages and sexes, within the burned-out shell of some kind of store. They were muttering among themselves as they scavenged in it. They were bedraggled, but seemed unconcerned by it. As I watched, two women picked up the same kettle at once, a large kettle, and then proceeded to slap at one another, each attempting to drive off the other and claim the loot. They reminded me of a couple of crows fighting over a cheese rind. They squawked and slapped and called one another vile names as they tugged at the opposing handles. The other folk paid them no mind, but went on with their own looting.

This was very strange behaviour for village folk. I had always heard of how after a raid, village folk banded together, cleaning out and making habitable what buildings were left standing, and then helping one another salvage cherished possessions, sharing and making do until cottages could be rebuilt, and store-buildings replaced. But these folk seemed completely careless that they had lost nearly everything and that family and friends had died in the raid. Instead, they had gathered to fight over what little was left.

This realization was horrifying enough to behold.

But I couldn’t feel them either.

I hadn’t seen or heard them until Chade pointed them out. I would have ridden right past them. And the other momentous thing that happened to me at that point was that I realized I was different from everyone else I knew. Imagine a seeing child growing up in a blind village, where no one else even suspects the possibility of such a sense. The child would have no words for colours, or for degrees of light. The others would have no conception of the way in which the child perceived the world. So it was in that moment, as we sat our horses and stared at the folk. For Chade wondered out loud, misery in his voice, ‘What is wrong with them? What’s got into them?’

I knew.

All the threads that run back and forth between folk, that twine from mother to child, from man to woman, all the kinships they extend to family and neighbour, to pets and stock, even to the fish of the sea and bird of the sky – all, all were gone.

All my life, without knowing it, I had depended on those threads of feelings to let me know when other live things were about. Dogs, horses, even chickens had them, as well as humans. And so I would look up at the door before Burrich entered it, or know there was one more new-born puppy in the stall, nearly buried under the straw. So I would wake when Chade opened the staircase. Because I could feel people. And that sense was the one that always alerted me first, that let me know to use my eyes and ears and nose as well, to see what they were about.