Полная версия:

Fossils, Finches and Fuegians: Charles Darwin’s Adventures and Discoveries on the Beagle

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2002

Copyright © Richard Keynes 2002

Richard Keynes asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007101900

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2017 ISBN: 9780007571673

Version: 2017-08-09

Dedication

To my mother

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Maps

Prologue

1 The Man who Walks with Henslow

2 The Strange Consequences of Stealing a Whale-Boat

3 Preparations for the Voyage

4 From Plymouth to the Cape Verde Islands

5 Across the Equator to Bahia

6 Rio de Janeiro

7 An Unquiet Trip from Monte Video to Buenos Aires

8 Digging up Fossils in the Cliffs at Bahia Blanca

9 The Return of the Fuegians to Their Homeland

10 First Visit to the Falkland Islands

11 Collecting Around Maldonado

12 A Meeting with General Rosas on the Ride from Patagones to Buenos Aires and Santa Fé

13 The Last of Monte Video

14 Christmas Day at Port Desire, and on to Port St Julian and Port Famine

15 Goodbye to Jemmy Button and Tierra del Fuego

16 Second Visit to the Falkland Islands

17 Ascent of the Rio Santa Cruz

18 Through the Straits of Magellan to Valparaiso

19 Valparaiso and Santiago

20 Chiloe and the Chonos Archipelago

21 The Great Earthquake of 1835 Hits Valdivia and Concepción

22 On Horseback from Santiago to Mendoza, and Back Over the Uspallata Pass

23 A Last Ride in the Andes, from Valparaiso to Copiapó

24 The Wreck of HMS Challenger

25 From Copiapó to Lima

26 The Galapagos Islands

27 Across the Pacific to Tahiti

28 New Zealand

29 Australia

30 Cocos Keeling Islands

31 Mauritius, Cape of Good Hope, St Helena and Ascension Island

32 A Quick Dash to Bahia and Home to Falmouth

33 Harvesting the Evidence

34 Farewell to Robert FitzRoy

Epilogue

Notes

Index

About the Author

Other Books By

About the Publisher

Maps

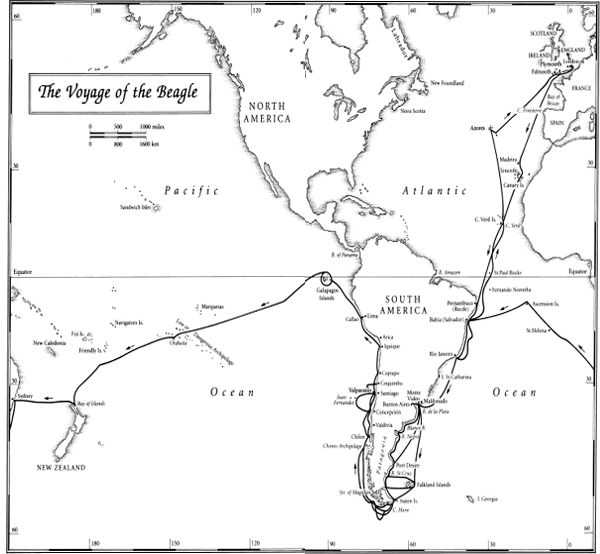

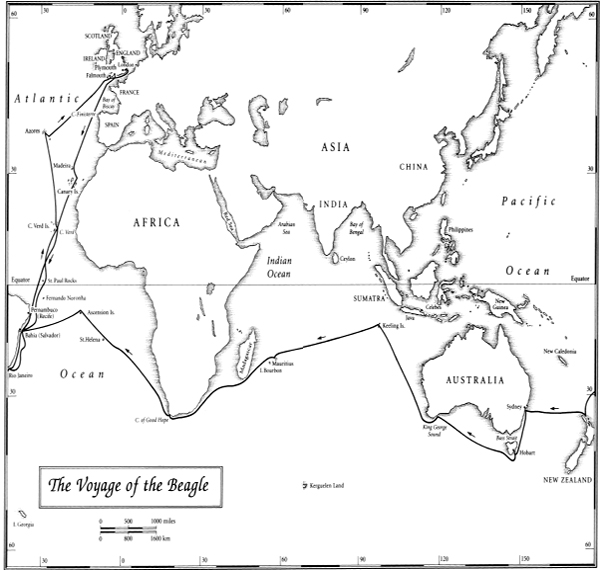

The Voyage of the Beagle

Geological map of part of North Wales

Tierra del Fuego

Charles’s Eight Principal Inland Expeditions in South America

Port San Julian

The Straits of Magellan

West Coast of Chile

The Galapagos Islands

North and South Keeling Islands

Prologue

In the autobiography written by Charles Darwin near the end of his life for the benefit of his children and descendants,1 he said:

The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career; yet it depended on so small a circumstance as my uncle offering to drive me 30 miles to Shrewsbury, which few uncles would have done, and on such a trifle as the shape of my nose. I have always felt that I owe to the voyage the first real training or education of my mind. I was led to attend closely to several branches of natural history, and thus my powers of observation were improved, though they were already fairly developed.

There is no dispute with Darwin’s own estimate of the importance of the voyage of the Beagle in the subsequent development of his scientific career. He himself provided a classical description of the voyage in his Journal of Researches,2 but his biographers other than Janet Browne have not covered his scientific research on the Beagle in much detail, while Alan Moorehead’s Darwin and the Beagle3 was mainly concerned with the affair as the exciting adventure that it undoubtedly was, and gave a distinctly misleading picture of the relations between Darwin and FitzRoy. The purpose of this book is to retell the whole story, starting from the haphazard events in Tierra del Fuego that led Robert FitzRoy to take the Beagle there again, with a ‘well-educated and scientific person’ as companion. Then it is shown how FitzRoy’s scientist had precisely the right talents to make highly effective use of the array of new scientific facts that were presented to him in South America and in the countries visited by the Beagle homeward bound round the far side of the world. And lastly it is explained how Charles Darwin’s findings on the Beagle soon started him on the path that in due course led him to the discovery of the principle of Natural Selection and of the Origin of Species.

My interest in South America was first aroused in 1951, when I had the good fortune to be invited by Professor Carlos Chagas Filho to be Visiting Reader that summer at the Instituto de Biofisica in Rio de Janeiro. My ignorance about Brazil was profound, but I did know that Professor Chagas had a good supply of electric eels at his laboratory. Moreover, Alan Hodgkin, leader of our group working at the Physiological Laboratory in Cambridge on the mechanism of conduction of the nervous impulse, had just developed an important new technique for recording electrical activity in living cells that I could usefully apply to investigate the properties of what Charles Darwin had described as the ‘wondrous’ organs4 in certain fishes that generated their powerful electrical discharges, though he had been puzzled about the manner of their evolution. So I spent two and a half happy months in Rio that summer, successfully unravelling the mystery of how the additive discharge of the electric organ was achieved.5 The job complete, and having accumulated a pocketful of cruzeiros in payment for my efforts, I then took the recently established direct flight in a Braniff DC-6 from Rio to Lima over the Mato Grosso and the Andes, and made the first of many journeys to Peru, briefly calling on fellow physiologists in Chile and Argentina on the way home, and getting back to Cambridge for the Michaelmas term at the beginning of October.

In August 1968 I had been visiting a Chilean colleague at Viña del Mar, near Valparaiso, for discussions on a joint study of the biophysics and physiology of giant nerve fibres, and was flying home via Buenos Aires. Here the British Council representative, knowing me to be a member of the Darwin family, asked me whether I had seen the Darwin collection belonging to Dr Armando Braun Menendez. I had not previously taken any particular interest in the voyage of the Beagle, but fortunately the Argentinian professor who was showing me round knew Dr Braun Menendez, and took me to call on him. His impressive collection of papers and books was concerned with the exploration of the southern seas, and the Darwin item consisted of two little portfolios of pencil drawings and watercolours made on board the Beagle by Conrad Martens, of whom I knew vaguely as the second of the ship’s official artists. I opened one of the portfolios to find the picture labelled by Martens as ‘Slinging the monkey. Port Desire – Decr 25, 1833’, which portrayed the ship’s crew engaged on the Royal Navy’s traditional celebration of Christmas Day, with the Beagle and Adventure anchored in the background. The picture bore the initials ‘RF’ at the top right-hand corner, though the Beagle’s Captain, Robert FitzRoy, evidently did not approve of every detail, because Martens had written below: ‘Note. Mainmast of the Beagle a little farther aft – Miz. Mast to rake more’. This graphic document, and others in the portfolios, opened an exciting new window for me on to the voyage of the Beagle, and launched me on an entirely new and rewarding field of part-time study.

On my return home, I consulted Nora Barlow, my godmother and mentor, and like my mother a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. Through her pioneer editions of Charles Darwin’s Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. “Beagle” (1933), Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle (1945), Darwin’s Autobiography (1958), his Ornithological Notes (1963), and Darwin and Henslow: The Growth of an Idea. Letters 1831–1860 (1967), Nora Barlow was the true founder of what is often known nowadays as the Darwin Industry. Her wisdom and kindness had no bounds, and my debt to her is immense.

With Lady Barlow’s encouragement, I set about assembling a catalogue of all the extant drawings and paintings made by Conrad Martens during his initial journey from England to Montevideo, where on 3 August 1833 he joined the Beagle as a replacement for the ship’s first official artist, Augustus Earle, who had been taken ill. Then I listed the drawings and paintings that he made in Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands, the Straits of Magellan, Chiloe and around Valparaiso, until in December 1834, there being no longer any space for him on the Beagle, he set sail for Australia. Here he established himself in Sydney as the leading artist of the period, and at the same time continued to paint developments of his Beagle drawings in watercolour, some of which he sold to Darwin, and others to Robert FitzRoy to be engraved as illustrations for the published accounts of the voyage. Selections from this material were reproduced in the first book that I edited, The Beagle Record (1979), to illustrate some of the places and people actually seen by Darwin and FitzRoy in South America. For the most immediate written records, I drew upon the vivid accounts in letters from Darwin to his sisters and to his mentor in Cambridge, Professor John Stevens Henslow, and also in what he himself called his ‘commonplace journal’, but which will be referred to here as the ‘Beagle Diary’ to distinguish it from his subsequently published Journal of Researches. In addition I made use of FitzRoy’s published account,6 his few surviving diaries, and some of his letters.

Fifty years after its publication, Nora Barlow’s edition of The Beagle Diary had long since gone out of print. Darwin’s splendid description of his daily life on the Beagle and ashore, sent home at intervals to his family in Shrewsbury, is one of the major classics of scientific exploration. My next task was therefore to produce a new version revised according to modern standards of transcription, with Nora Barlow’s very rare errors put right, and a new introduction and footnotes. This was published in 1988, and has recently been reprinted in paperback.7

Two substantial Darwin manuscripts still remained unpublished at the Cambridge University Library, namely the Zoology Notes8 and the Geology Notes9,10 made on the Beagle. Apart from a brief account of some observations made in Edinburgh in 1827,11 these were his first scientific writings, containing a detailed record of all that he observed and collected during the four-and-three-quarter years of the voyage. Their importance is that here, and in his letters to Henslow,12 it is possible to trace the first beginnings of Darwin’s thinking about the evolution not only of the animal kingdom but also of the face of the earth.

After retiring in 1986 from administration and teaching in Cambridge, I had more time at my disposal, so in addition to visiting the marine laboratory at Roscoff in Brittany every autumn for continuation of some experimental work, I embarked on a transcription13 of Darwin’s Zoology Notes and Specimen Lists. They comprise some hundreds of quarto pages of notes, with descriptions of 1500 specimens preserved in Spirits of Wine, and some 3500 not in Spirits. In order to identify the insects and marine invertebrates collected by Darwin, I needed a great deal of help from experts on their taxonomy, but the vertebrates had mostly been covered in the five parts of The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle published in 1839–1843.14 Completion of the task has kept me busy for about ten years, but it has now at last been finished. The Geology Notes have not as yet been transcribed and published, occupying as they do around four times as many pages as the Zoology Notes. However, articles by Secord,15 Herbert16 and Rhodes17 have discussed them helpfully, as has Janet Browne’s account of the voyage.18 Moreover, photocopies of the MSS are available at the Cambridge University Library for study by anyone well practised at reading Darwin’s reasonably legible handwriting.

If any of my readers feel that they would like to become better acquainted with one of their forebears, I can recommend the course that I adopted thanks to that chance introduction in Buenos Aires in 1968. When you have transcribed several hundred thousand words of his writings, concerned with places a few of which you have seen for yourself not too greatly changed 160 years later, you may once in a while almost feel that you are talking to him. But it helps to be lucky enough to have a forebear who was as friendly to all men, and as constructively critical and honest about his own ideas, as Charles Darwin always was.

Richard Darwin KeynesCambridge, July 2001

CHAPTER 1

The Man who Walks with Henslow

Charles Robert Darwin was born at The Mount, Shrewsbury, on 12 February 1809, the second son and fifth child of Dr Robert Waring Darwin.

His genetic make-up in the male line was strongly scientific, although his father combined a position as one of the leading physicians in the Midlands not with science, but with acting widely as a private financial adviser to the gentry of the region. Charles would later have high praise for his father’s powers of observation, and for his sympathy with his patients, but considered that his mind was not truly scientific. Robert’s wealth was nevertheless as valuable an inheritance for his son as a gene for science, not only paying for Charles’s board and lodging on the Beagle when he sailed as an unofficial scientist and companion to the Captain, but also enabling him to pursue a scientific career single-mindedly for the rest of his life, without ever having to earn his living.

However, his grandfathers, Dr Erasmus Darwin of Lichfield and Josiah Wedgwood I the potter, who built a model factory at Etruria near Stoke-on-Trent, were two of the leading scientists and technologists of their time. Both Fellows of the Royal Society, they were also founding members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which played the principal intellectual part in the establishment of the Industrial Revolution in England. Erasmus Darwin19 was primarily a practising physician, but his prodigious energies overflowed in many other directions, as a poet, an inventor of mechanical devices of various kinds, a pioneer in meteorology and in the description of photosynthesis, and not least as author of an immense medical treatise entitled Zoonomia,* and of a fine poem, The Temple of Nature, in which as we shall see he made an important contribution to his grandson’s Theory of Evolution. Josiah Wedgwood I made radical improvements in the handling of china clay, founded a famous pottery, and developed a canal system for the transport of his products. The chemists of Europe came to him for their glassware and retorts, and in due course his son Josiah Wedgwood II provided his nephews Erasmus and Charles with fireproof china dishes manufactured at the pottery, and an industrial thermometer for their private laboratory.

Charles recorded that at a very early age he had a passion for collecting ‘all sorts of things, shells, seals, franks, coins, and minerals … which leads a man to be a systematic naturalist, a virtuoso or a miser’. Throughout his life he also exercised a scientifically useful taste for making careful lists, whether of his various collections, of the game that he had killed, of books that he had read or intended to read, of the pros and cons of marriage, or of his household accounts.

During his formal education at Shrewsbury School, where like his elder brother Erasmus he boarded for some years, he was taught mainly classics, ancient geography and history, and a little mathematics, but there was no place for science in the curriculum. However, their grandfathers’ strong interest in chemistry managed to break through in both boys, first in Erasmus and then in Charles, and together they set up in an outhouse at home what they grandly called their ‘Laboratory’. Here they could pursue a hobby fashionable at the time in the upper classes for investigating the composition of various domestic materials, sometimes after purification of their constituents by crystallisation, though they were seldom able to extract sufficient funds from their father to provide any really sophisticated chemical apparatus. For a while the application of elementary crystallography to his collection of rocks and stones was one of Charles’s favourite occupations.

In 1822 Erasmus left school, and was sent to study at Cambridge, where he wrote a helpful series of letters to Charles with detailed instructions for further experiments. This encouraged Charles to examine the effect on different substances of heating them over an open flame, sometimes with a blow-pipe at the gaslight in his bedroom at school, earning him the nickname of ‘Gas’ and the strong disapproval of the headmaster. Over this period, Charles delighted in devising simple instruments for performance of his tests, and under the tuition of Erasmus served a useful initial apprenticeship in the art of scientific experimentation.

Robert Darwin now decided that Erasmus should proceed from Cambridge to Edinburgh University as he had done himself in order to take an M.B. degree, and that Charles should leave school at the age of sixteen and accompany his brother to Edinburgh in October 1825 with the same object. The plan did not quite work out, for although Erasmus did eventually pass the Cambridge M.B. exam in 1828, his poor health led to his retirement to London as a gentleman of leisure, and he never practised. Charles, on the other hand, having signed up for the traditional courses on anatomy, surgery, the practice of physic, and materia medica, the remedial substances used in medicine, which his father and grandfather had taken in their day, soon found that many of the lectures were now sadly out of date, and that conditions in the dissecting room and on two occasions in the operating room were so highly distasteful that he felt unable to continue on the course. It was not until the end of his second year that he was at last able to confess to his father his determination to abandon medicine as a career, but in the meantime Edinburgh provided other avenues to fill his time that assisted materially in his development as a scientist.

During his first year at Edinburgh, Charles took regular walks with Erasmus on the shores of the Firth of Forth, where he made his first acquaintance with some of the marine animals that later occupied him so intensively on the Beagle. At the same time he maintained his interest in ornithology, and arranged to have lessons on stuffing birds from a ‘blackamoor’ who had been taught taxidermy by the naturalist Charles Waterton. He and Erasmus also revived their knowledge of chemistry and related areas of geology by attending the stimulating lectures and demonstrations given by Thomas Charles Hope, Professor of Chemistry in the university from 1799 to 1843.

In 1826, Erasmus had remained at home, and Charles was left to fend for himself. He attended Robert Jameson’s popular series of extracurricular lectures covering meteorology, hydrography, mineralogy, geology, botany and zoology, but said many years later that ‘they were incredibly dull. The sole effect they produced on me was the determination never as long as I lived to read a book on Geology or in any way to study the science.’ Although it was true that Jameson’s style of lecturing did not inspire his audience, Charles’s copy of Jameson’s Manual of Mineralogy is heavily annotated, and provided him with a valuable source of practical information for his subsequent geological studies. He also benefited from exposure to the critical clash between Hope’s Huttonian views and Jameson’s preference for the Wernerian doctrine,* soon coming down firmly on Hope’s side. In any case, any temporary prejudice that Charles may have had against geology did not last long, and in due course was banished by Professors Henslow and Sedgwick after his arrival at Cambridge.

In November, Charles became a member of the Plinian Society, named after Pliny the Elder, author of a famous account of the natural history of ancient Rome, at which a small group of undergraduates would meet informally for discussions of natural history or sometimes to go on collecting expeditions, but from participation in which the university professors were traditionally banned. He was also taken as a guest from time to time to the august Wernerian Society, whose membership was restricted to graduates, and whose proceedings were published in a series of learned memoirs. At a meeting of the Wernerian Society on 16 December 1826, he listened attentively to a paper on the buzzard in which the great American ornithologist and artist John James Audubon, who had recently arrived in Edinburgh to find an engraver for the first ten plates of his Birds of America, exploded the currently fashionable view of the extraordinary power of smelling possessed by vultures. When nine years later Charles was making observations in Chile on the behaviour of condors, he was happy to find himself in agreement with Audubon’s conclusions.

The senior member of the Plinian Society was at that time Robert Grant, then aged thirty-three and a mere lecturer on invertebrate animals at an extramural anatomy school, who had graduated as a doctor in 1814, travelled extensively on the Continent, and studied in Paris with the zoologist and anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769–1832). Soon Charles was taken by Grant to collect a variety of animals along the shores in the neighbourhood of Leith, and to go out with fishermen on the waters of the Firth of Forth. On these trips he was sometimes accompanied by another medical student, John Coldstream, who later advised him helpfully about fishing nets. Grant also taught Charles how to dissect specimens under sea water with the aid of a crude single-lens microscope, and gave him a valuable training in marine biology, with an emphasis on the importance of developmental studies on invertebrates, which was taken up with enthusiasm by a pupil who all too quickly outshone his master.