Полная версия:

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

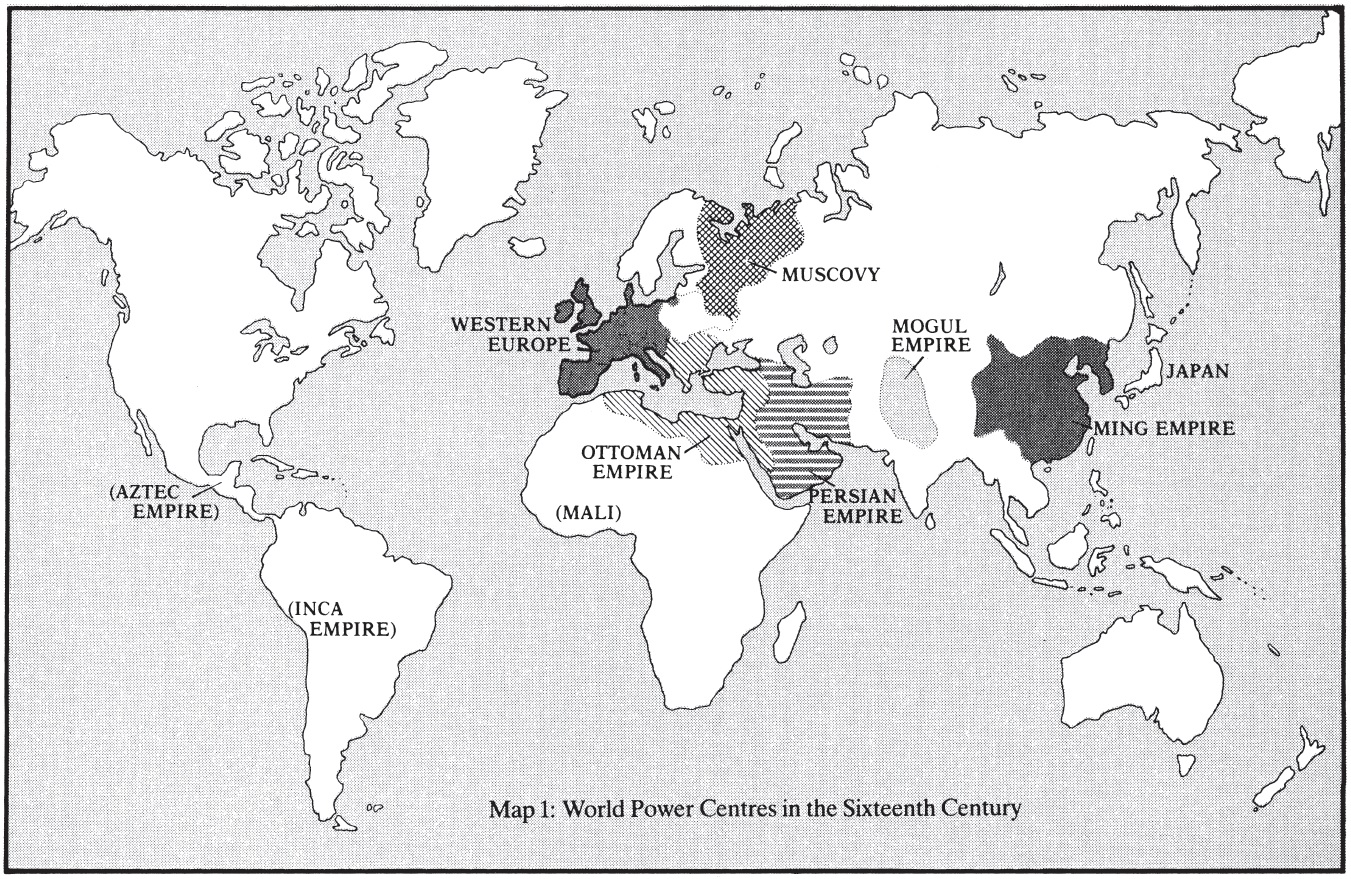

To readers brought up to respect ‘western’ science, the most striking feature of Chinese civilization must be its technological precocity. Huge libraries existed from early on. Printing by movable type had already appeared in eleventh-century China, and soon large numbers of books were in existence. Trade and industry, stimulated by the canal-building and population pressures, were equally sophisticated. Chinese cities were much larger than their equivalents in medieval Europe, and Chinese trade routes as extensive. Paper money had earlier expedited the flow of commerce and the growth of markets. By the later decades of the eleventh century there existed an enormous iron industry in North China, producing around 125,000 tons per annum, chiefly for military and governmental use – the army of over a million men was, for example, an enormous market for iron goods. It is worth remarking that this production figure was far larger than the British iron output in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, seven centuries later! The Chinese were also probably the first to invent true gunpowder; and cannon were used by the Ming to overthrow their Mongol rulers in the late fourteenth century.4

Given this evidence of cultural and technological advance, it is also not surprising to learn that the Chinese had turned to overseas exploration and trade. The magnetic compass was another Chinese invention, some of their junks were as large as later Spanish galleons, and commerce with the Indies and the Pacific islands was potentially as profitable as that along the caravan routes. Naval warfare had been conducted on the Yangtze many decades earlier – in order to subdue the vessels of Sung China in the 1260s, Kublai Khan had been compelled to build his own great fleet of fighting ships equipped with projectile-throwing machines – and the coastal grain trade was booming in the early fourteenth century. In 1420, the Ming navy was recorded as possessing 1,350 combat vessels, including 400 large floating fortresses and 250 ships designed for long-range cruising. Such a force eclipsed, but did not include, the many privately managed vessels which were already trading with Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia, and even East Africa by that time, and bringing revenue to the Chinese state, which sought to tax this maritime commerce.

The most famous of the official overseas expeditions were the seven long-distance cruises undertaken by the admiral Cheng Ho between 1405 and 1433. Consisting on occasions of hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of men, these fleets visited ports from Malacca and Ceylon to the Red Sea entrances and Zanzibar. Bestowing gifts upon deferential local rulers on the one hand, they compelled the recalcitrant to acknowledge Peking on the other. One ship returned with giraffes from East Africa to entertain the Chinese emperor; another with a Ceylonese chief who had been unwise enough not to acknowledge the supremacy of the Son of Heaven. (It must be noted, however, that the Chinese apparently never plundered nor murdered – unlike the Portuguese, Dutch, and other European invaders of the Indian Ocean.) From what historians and archaeologists can tell us of the size, power, and seaworthiness of Cheng Ho’s navy – some of the great treasure ships appear to have been around 400 feet long and displaced over 1,500 tons – they might well have been able to sail around Africa and ‘discover’ Portugal several decades before Henry the Navigator’s expeditions began earnestly to push south of Ceuta.5

But the Chinese expedition of 1433 was the last of the line, and three years later an imperial edict banned the construction of seagoing ships; later still, a specific order forbade the existence of ships with more than two masts. Naval personnel would henceforth be employed on smaller vessels on the Grand Canal. Cheng Ho’s great warships were laid up and rotted away. Despite all the opportunities which beckoned overseas, China had decided to turn its back on the world.

There was, to be sure, a plausible strategical reason for this decision. The northern frontiers of the empire were again under some pressure from the Mongols, and it may have seemed prudent to concentrate military resources in this more vulnerable area. Under such circumstances a large navy was an expensive luxury, and in any case, the attempted Chinese expansion southward into Annam (Vietnam) was proving fruitless and costly. Yet this quite valid reasoning does not appear to have been reconsidered when the disadvantages of naval retrenchment later became clear: within a century or so, the Chinese coastline and even cities on the Yangtze were being attacked by Japanese pirates, but there was no serious rebuilding of an imperial navy. Even the repeated appearance of Portuguese vessels off the China coast did not force a reassessment.* Defence on land was all that was required, the mandarins reasoned, for had not all maritime trade by Chinese subjects been forbidden in any case?

Apart from the costs and other disincentives involved, therefore, a key element in China’s retreat was the sheer conservatism of the Confucian bureaucracy6 – a conservatism heightened in the Ming period by resentment at the changes earlier forced upon them by the Mongols. In this ‘Restoration’ atmosphere, the all-important officialdom was concerned to preserve and recapture the past, not to create a brighter future based upon overseas expansion and commerce. According to the Confucian code, warfare itself was a deplorable activity and armed forces were made necessary only by the fear of barbarian attacks or internal revolts. The mandarins’ dislike of the army (and the navy) was accompanied by a suspicion of the trader. The accumulation of private capital, the practice of buying cheap and selling dear, the ostentation of the nouveau riche merchant, all offended the elite, scholarly bureaucrats – almost as much as they aroused the resentments of the toiling masses. While not wishing to bring the entire market economy to a halt, the mandarins often intervened against individual merchants by confiscating their property or banning their business. Foreign trade by Chinese subjects must have seemed even more dubious to mandarin eyes, simply because it was less under their control.

This dislike of commerce and private capital does not conflict with the enormous technological achievements mentioned above. The Ming rebuilding of the Great Wall of China and the development of the canal system, the ironworks, and the imperial navy were for state purposes, because the bureaucracy had advised the emperor that they were necessary. But just as these enterprises could be started, so also could they be neglected. The canals were permitted to decay, the army was periodically starved of new equipment, the astronomical clocks (built c. 1090) were disregarded, the ironworks gradually fell into desuetude. These were not the only disincentives to economic growth. Printing was restricted to scholarly works and not employed for the widespread dissemination of practical knowledge, much less for social criticism. The use of paper currency was discontinued. Chinese cities were never allowed the autonomy of those in the West; there were no Chinese burghers, with all that that term implied; when the location of the emperor’s court was altered, the capital city had to move as well. Yet without official encouragement, merchants and other entrepreneurs could not thrive; and even those who did acquire wealth tended to spend it on land and education, rather than investing in protoindustrial development. Similarly, the banning of overseas trade and fishing took away another potential stimulus to sustained economic expansion; such foreign trade as did occur with the Portuguese and Dutch in the following centuries was in luxury goods and (although there were doubtless many evasions) controlled by officials.

In consequence, Ming China was a much less vigorous and enterprising land than it had been under the Sung dynasty four centuries earlier. There were improved agricultural techniques in the Ming period, to be sure, but after a while even this more intensive farming and the use of marginal lands found it harder to keep pace with the burgeoning population; and the latter was only to be checked by those Malthusian instruments of plague, floods, and war, all of which were very difficult to handle. Even the replacement of the Mings by the more vigorous Manchus after 1644 could not halt the steady relative decline.

One final detail can summarize this tale. In 1736 – just as Abraham Darby’s ironworks at Coalbrookdale were beginning to boom – the blast furnaces and coke ovens of Honan and Hopei were abandoned entirely. They had been great before the Conqueror had landed at Hastings. Now they would not resume production until the twentieth century.

The Muslim World

Even the first of the European sailors to visit China in the early sixteenth century, although impressed by its size, population, and riches, might have observed that this was a country which had turned in on itself. That remark certainly could not then have been made of the Ottoman Empire, which was then in the middle stages of its expansion and, being nearer home, was correspondingly much more threatening to Christendom. Viewed from the larger historical and geographical perspective, in fact, it would be fair to claim that it was the Muslim states which formed the most rapidly expanding forces in world affairs during the sixteenth century. Not only were the Ottoman Turks pushing westward, but the Safavid dynasty in Persia was also enjoying a resurgence of power, prosperity, and high culture, especially in the reigns of Ismail I (1500–24) and Abbas I (1587–1629); a chain of strong Muslim khanates still controlled the ancient Silk Road via Kashgar and Turfan to China, not unlike the chain of West African Islamic states such as Bornu, Sokoto, and Timbuktu; the Hindu Empire in Java was overthrown by Muslim forces early in the sixteenth century; and the king of Kabul, Babur, entering India by the conqueror’s route from the northwest, established the Mogul Empire in 1526. Although this hold on India was shaky at first, it was successfully consolidated by Babur’s grandson Akbar (1556–1605) who carved out a northern Indian empire stretching from Baluchistan in the west to Bengal in the east. Throughout the seventeenth century, Akbar’s successors pushed farther south against the Hindu Marathas, just at the same time as the Dutch, British, and French were entering the Indian peninsula from the sea, and of course in a much less substantial form. To these secular signs of Muslim growth one must add the vast increase in numbers of the faithful in Africa and the Indies, against which the proselytization by Christian missions paled in comparison.

But the greatest Muslim challenge to early modern Europe lay, of course, with the Ottoman Turks, or, rather, with their formidable army and the finest siege train of the age. Already by the beginning of the sixteenth century their domains stretched from the Crimea (where they had overrun Genoese trading posts) and the Aegean (where they were dismantling the Venetian Empire) to the Levant. By 1516, Ottoman forces had seized Damascus, and in the following year they entered Egypt, shattering the Mamluk forces by the use of Turkish cannon. Having thus closed the spice route from the Indies, they moved up the Nile and pushed through the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean, countering the Portuguese incursions there. If this perturbed Iberian sailors, it was nothing to the fright which the Turkish armies were giving the princes and peoples of eastern and southern Europe. Already the Turks held Bulgaria and Serbia, and were the predominant influence in Wallachia and all around the Black Sea; but, following the southern drive against Egypt and Arabia, the pressure against Europe was resumed under Suleiman (1520–66). Hungary, the great eastern bastion of Christendom in these years, could no longer hold off the superior Turkish armies and was overrun following the battle of Mohacs in 1526 – the same year, coincidentally, as Babur gained the victory at Panipat by which the Mogul Empire was established. Would all of Europe soon go the way of northern India? By 1529, with the Turks besieging Vienna, this must have appeared a distinct possibility to some. In actual fact, the line then stabilized in northern Hungary and the Holy Roman Empire was preserved; but thereafter the Turks presented a constant danger and exerted a military pressure which could never be fully ignored. Even as late as 1683, they were again besieging Vienna.7

Almost as alarming, in many ways, was the expansion of Ottoman naval power. Like Kublai Khan in China, the Turks had developed a navy only in order to reduce a seagirt enemy fortress – in this case, Constantinople, which Sultan Mehmet blockaded with large galleys and hundreds of smaller craft to assist the assault of 1453. Thereafter, formidable galley fleets were used in operations across the Black Sea, in the southward push toward Syria and Egypt, and in a whole series of clashes with Venice for control of the Aegean islands, Rhodes, Crete, and Cyprus. For some decades of the early sixteenth century Ottoman sea power was kept at arm’s length by Venetian, Genoese, and Habsburg fleets; but by midcentury, Muslim naval forces were active all the way along the North African coast, were raiding ports in Italy, Spain, and the Balearics, and finally managed to take Cyprus in 1570–1, before being checked at the battle of Lepanto.8

The Ottoman Empire was, of course, much more than a military machine. A conquering elite (like the Manchus in China), the Ottomans had established a unity of official faith, culture, and language over an area greater than the Roman Empire, and over vast numbers of subject peoples. For centuries before 1500 the world of Islam had been culturally and technologically ahead of Europe. Its cities were large, well-lit, and drained, and some of them possessed universities and libraries and stunningly beautiful mosques. In mathematics, cartography, medicine, and many other aspects of science and industry – in mills, gun-casting, lighthouses, horsebreeding – the Muslims had enjoyed a lead. The Ottoman system of recruiting future janissaries from Christian youth in the Balkans had produced a dedicated, uniform corps of troops. Tolerance of other races had brought many a talented Greek, Jew, and Gentile into the sultan’s service – a Hungarian was Mehmet’s chief gun-caster in the Siege of Constantinople. Under a successful leader like Suleiman I, a strong bureaucracy supervised fourteen million subjects – this at a time when Spain had five million and England a mere two and a half million inhabitants. Constantinople in its heyday was bigger than any European city, possessing over 500,000 inhabitants in 1600.

Yet the Ottoman Turks, too, were to falter, to turn inward, and to lose the chance of world domination, although this became clear only a century after the strikingly similar Ming decline. To a certain extent it could be argued that this process was the natural consequence of earlier Turkish successes: the Ottoman army, however well administered, might be able to maintain the lengthy frontiers but could hardly expand farther without enormous cost in men and money; and Ottoman imperialism, unlike that of the Spanish, Dutch, and English later, did not bring much in the way of economic benefit. By the second half of the sixteenth century the empire was showing signs of strategical overextension, with a large army stationed in central Europe, an expensive navy operation in the Mediterranean, troops engaged in North Africa, the Aegean, Cyprus, and the Red Sea, and reinforcements needed to hold the Crimea against a rising Russian power. Even in the Near East there was no quiet flank, thanks to a disastrous religious split in the Muslim world which occurred when the Shi’ite branch, based in Iraq and then in Persia, challenged the prevailing Sunni practices and teachings. At times, the situation was not unlike that of the contemporary religious struggles in Germany, and the sultan could maintain his dominance only by crushing Shi’ite dissidents with force. However, across the border the Shi’ite kingdom of Persia under Abbas the Great was quite prepared to ally with European states against the Ottomans, just as France had worked with the ‘infidel’ Turk against the Holy Roman Empire. With this array of adversaries, the Ottoman Empire would have needed remarkable leadership to have maintained its growth; but after 1566 there reigned thirteen incompetent sultans in succession.

External enemies and personal failings do not, however, provide the full explanation. The system as a whole, like that of Ming China, increasingly suffered from some of the defects of being centralized, despotic, and severely orthodox in its attitude toward initiative, dissent, and commerce. An idiot sultan could paralyse the Ottoman Empire in the way that a pope or Holy Roman emperor could never do for all Europe. Without clear directives from above, the arteries of the bureaucracy hardened, preferring conservatism to change, and stifling innovation. The lack of territorial expansion and accompanying booty after 1550, together with the vast rise in prices, caused discontented janissaries to turn to internal plunder. Merchants and entrepreneurs (nearly all of whom were foreigners), who earlier had been encouraged, now found themselves subject to unpredictable taxes and outright seizures of property. Ever higher dues ruined trade and depopulated towns. Perhaps worst affected of all were the peasants, whose lands and stock were preyed upon by the soldiers. As the situation deteriorated, civilian officials also turned to plunder, demanding bribes and confiscating stocks of goods. The costs of war and the loss of Asiatic trade during the struggle with Persia intensified the government’s desperate search for new revenues, which in turn gave greater powers to unscrupulous tax farmers.9

To a distinct degree, the fierce response to the Shi’ite religious challenge reflected and anticipated a hardening of official attitudes toward all forms of free thought. The printing press was forbidden because it might disseminate dangerous opinions. Economic notions remained primitive: imports of western wares were desired, but exports were forbidden; the guilds were supported in their efforts to check innovation and the rise of ‘capitalist’ producers; religious criticism of traders intensified. Contemptuous of European ideas and practices, the Turks declined to adopt newer methods for containing plagues; consequently, their populations suffered more from severe epidemics. In one truly amazing fit of obscurantism, a force of janissaries destroyed a state observatory in 1580, alleging that it had caused a plague.10 The armed services had become, indeed, a bastion of conservatism. Despite noting, and occasionally suffering from, the newer weaponry of European forces, the janissaries were slow to modernize themselves. Their bulky cannons were not replaced by the lighter cast-iron guns. After the defeat at Lepanto, they did not build the larger European type of vessels. In the south, the Muslim fleets were simply ordered to remain in the calmer waters of the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, thus obviating the need to construct oceangoing vessels on the Portuguese model. Perhaps technical reasons help to explain these decisions, but cultural and technological conservatism also played a role (by contrast, the irregular Barbary corsairs swiftly adopted the frigate type of warship).

The above remarks about conservatism could be made with equal or even greater force about the Mogul Empire. Despite the sheer size of the kingdom at its height and the military genius of some of its emperors, despite the brilliance of its courts and craftsmanship of its luxury products, despite even a sophisticated banking and credit network, the system was weak at the core. A conquering Muslim elite lay on top of a vast mass of poverty-stricken peasants chiefly adhering to Hinduism. In the towns themselves there were very considerable numbers of merchants, bustling markets, and an attitude toward manufacture, trade, and credit among Hindu business families which would make them excellent examples of Weber’s Protestant ethic. As against this picture of an entrepreneurial society just ready for economic ‘takeoff’ before it became a victim of British imperialism, there are the gloomier portrayals of the many indigenous retarding factors in Indian life. The sheer rigidity of Hindu religious taboos militated against modernization: rodents and insects could not be killed, so vast amounts of foodstuffs were lost; social mores about handling refuse and excreta led to permanently insanitary conditions, a breeding ground for bubonic plagues; the caste system throttled initiative, instilled ritual, and restricted the market; and the influence wielded over Indian local rulers by the Brahman priests meant that this obscurantism was effective at the highest level. Here were social checks of the deepest sort to any attempts at radical change. Small wonder that later many Britons, having first plundered and then tried to govern India in accordance with Utilitarian principles, finally left with the feeling that the country was still a mystery to them.11

But the Mogul rule could scarcely be compared with administration by the Indian Civil Service. The brilliant courts were centres of conspicuous consumption on a scale which the Sun King at Versailles might have thought excessive. Thousands of servants and hangers-on, extravagant clothes and jewels and harems and menageries, vast arrays of bodyguards, could be paid for only by the creation of a systematic plunder machine. Tax collectors, required to provide fixed sums for their masters, preyed mercilessly upon peasant and merchant alike; whatever the state of the harvest or trade, the money had to come in. There being no constitutional or other checks – apart from rebellion – upon such depredations, it was not surprising that taxation was known as ‘eating’. For this colossal annual tribute, the population received next to nothing. There was little improvement in communications, and no machinery for assistance in the event of famine, flood, and plague – which were, of course, fairly regular occurrences. All this makes the Ming dynasty appear benign, almost progressive, by comparison. Technically, the Mogul Empire was to decline because it became increasingly difficult to maintain itself against the Marathas in the south, the Afghanis in the north, and, finally, the East India Company. In reality, the causes of its decay were much more internal than external.

Two Outsiders – Japan and Russia

By the sixteenth century there were two other states which, although nowhere near the size and population of the Ming, Ottoman, and Mogul empires, were demonstrating signs of political consolidation and economic growth. In the Far East, Japan was taking forward steps just as its large Chinese neighbour was beginning to atrophy. Geography gave a prime strategical asset to the Japanese (as it did to the British), for insularity offered a protection from overland invasion which China did not possess. The gap between the islands of Japan and the Asiatic mainland was by no means a complete one, however, and a great deal of Japanese culture and religion had been adapted from the older civilization. But whereas China was run by a unified bureaucracy, power in Japan lay in the hands of clan-based feudal lordships and the emperor was but a cipher. The centralized rule which had existed in the fourteenth century had been replaced by a constant feuding between the clans – akin, as it were, to the strife among their equivalents in Scotland. This was not the ideal circumstance for traders and merchants, but it did not check a very considerable amount of economic activity. At sea, as on land, entrepreneurs jostled with warlords and military adventurers, each of whom detected profit in the East Asian maritime trade. Japanese pirates scoured the coasts of China and Korea for plunder, while simultaneously other Japanese welcomed the chance to exchange goods with the Portuguese and Dutch visitors from the West. Christian missions and European wares penetrated Japanese society far more easily than they did an aloof, self-contained Ming Empire.12