Полная версия:

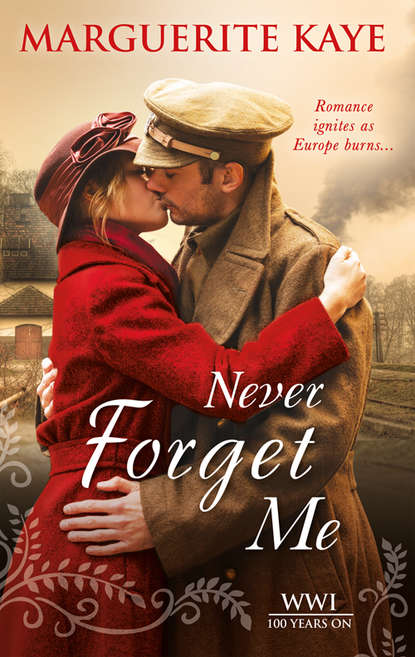

Never Forget Me

‘Let us proceed with the tour at once.’ Because the sooner this is over, the sooner I shall be rid of you, she implied as she strode past him, her nose in the air, knowing that she must look perfectly ridiculous as well as appearing dreadfully rude. ‘Good morning, Colonel.’

‘My daughter is right,’ she heard her father say, ‘the sooner the better. If that is all for now, Colonel?’

‘A few signatures, the rest can be ironed out later. As I said, I shan’t be far away. Hoping to bag a few grouse while I’m here, actually. Maybe even a salmon. Patterson was telling me there is excellent fishing on his stretch of the river. In the old days...’

The meeting was clearly over. Flora fumbled with the latch.

‘Allow me.’

Corporal Cassell reached around her, the sleeve of his jacket brushing her arm, ushering her through the open door. She was absurdly conscious of how slight she was compared to his broad physique. ‘Thank you.’

‘You’re welcome.’ She had expected him to return to the drawing room, but instead he followed her out to the Great Hall, wandering over to the stone fireplace and studying the display of claymores ranged in a wheel on the wall above it. ‘Do you keep these in readiness to repel an invasion by the English?’ he asked.

Flora rarely lost her temper, but she felt her hackles rise. This man was insufferable. ‘It may have escaped your notice, but we are actually fighting on the same side in this particular war.’

‘I doubt you and I will ever be on the same side, Miss Carmichael,’ Corporal Cassell said, turning his attention to the array of muskets in a case by the window. ‘You’d do well to make sure the colonel doesn’t clap eyes on these, else he’ll be requisitioning them.’

‘They would be of little use, since they are over a hundred years old.’

‘I’m willing to bet they’re still a damn sight more effective than what they’ve been giving our boys to train with,’ he exclaimed with surprising viciousness. ‘Broom handles, pitchforks, guns minus bullets if they are very lucky,’ he added, in answer to her enquiring look. ‘This war has caught the army on the hop. If you could but see...’ He stopped abruptly.

‘If I could but see what, Corporal Cassell?’

He shrugged and turned away to look at a large flag displayed on the wall.

‘The standard you are looking at was borne at Culloden,’ Flora said, addressing his back. ‘Though some of the clan fought for Bonnie Prince Charlie, others were on the side of the crown.’

The corporal made no reply. Thoroughly riled, and determined to force him to acknowledge her presence, Flora went to stand beside him. ‘Above the standard is our family crest, which is also carved over the front door. Tout Jour Prest. It means...’

‘Always ready. You see, I am not wholly uneducated.’

‘I did not think for a moment that you were. Why do you dislike me so much, Corporal?’

He twisted round suddenly, taking her off guard. ‘I bear you no ill will personally, Miss Carmichael, but I do not approve of your type.’

‘My type?’ His eyes, she realised, were not black but a very dark chocolate-brown. Though he clearly intended to intimidate her, she found the way he looked at her challenging. It was deliberately provocative. ‘And what, pray tell, do you mean by that?’

‘All this.’ He swept his arm wide. ‘This little toy castle of yours. All these guns and shields and standards commemorating years of repression. A monument, Miss Carmichael, to the rich and privileged who expect others to do the filthy business of earning their living for them.’

‘My father works extremely hard.’

‘Collecting rents.’

‘He does not— Good grief, are you some sort of communist?’

She could not help but be pleased at the surprise on his face. ‘What on earth would you know about communism?’ he demanded.

‘You haven’t answered my question.’

‘I am a socialist and proud of it.’

‘Like Mr Keir Hardie? He has made himself most unpopular by campaigning against the war. Are you also a pacifist?’

‘A conchie? Hardly, given my uniform and my rank. What do you know of Keir Hardie? I wouldn’t have thought someone like you would be interested in him.’

‘Someone like me! A female, do you mean, or one of my class? Do you have any idea how patronising that sounds? Silly question, of course you do.’

‘I did not intend to insult you.’

‘Yes, you did, Corporal Cassell.’ Flora glared at him. ‘Please, feel free to continue with your barbs. Being a patriot, I am delighted to afford you the opportunity to practise something that gives you such obvious pleasure.’

To her astonishment, he burst out laughing. ‘I will when I can think of one. I must say, you are not at all what I was expecting.’

His backhanded compliment should most decidedly not be making her feel quite so pleased. Quite the contrary, she should have taken extreme umbrage by now, and left him to his own devices. Instead Flora discovered that she was enjoying herself. Corporal Cassell was rude and he made the most extraordinarily sweeping assumptions, but he did not talk to her as if she was witless. ‘I have never met a socialist before. Are they all as outspoken as you?’

‘I don’t know. I’ve never met a laird’s daughter before. Are they all as feisty as you?’

‘Oh, I should think so. Centuries of trampling over serfs and turning crofters out of their homes into the winter snows leave their mark, you know.’

He smiled wryly, acknowledging the hit. ‘And then there is the red hair. Though it would be a crime to label it something so mundane as red.’

She knew she ought not to be standing here exchanging banter with him. She was also quite certain she should not be feeling this exhilarating sense of anticipation, as if she were getting ready to jump into the loch, knowing it would be shockingly cold but unbearably tempted by its deceptively blue embrace on a warm summer’s day. ‘What, then, would you call it?’ Flora asked.

The corporal reached out to touch the lock that hung over her forehead, twining it around his finger. ‘Autumn,’ he said thoughtfully.

She caught her breath. ‘That’s not a colour.’

‘It is now.’

The door to the drawing room opened, and he sprang away from her. ‘Flora?’ her father said.

‘I was showing Corporal Cassell our collection of firearms.’

The laird drew her one of his inscrutable looks before turning back to the colonel. ‘Good day to you. I will see you in a few days, but in the meantime you can reach me by telephone, and I’m sure my daughter will keep me fully briefed.’

With a gruff goodbye to the corporal, her father picked up his walking stick and headed for the front door where the deerhounds awaited him. He’d be off for a long tramp across the moors. Her father supported the war unequivocally and would like as not have enlisted himself if he’d been of age, but Glen Massan House was in his blood, and giving it up was no easy sacrifice to make.

A horrible premonition of the other, much more painful sacrifices her family might ultimately have to make made Flora feel quite sick, but she resolutely pushed the thought away. There was no point in imagining the worst when there was work to be done. Besides, neither of her brothers was currently in the firing line, for which she was guiltily grateful.

She turned her attention to the forecourt, where the corporal was in earnest conversation with his colonel. The engine of the staff car was already running. She could not hear what was being said, but she could tell the Welshman was not happy. Eventually, he stepped back and saluted. The car drove off in a flurry of gravel, and the corporal re-joined her.

‘What do you intend to use our house for?’ Flora asked.

‘It’s supposed to be hush-hush, though I can’t imagine why. You’re not a German spy by any chance, are you?’ he asked sardonically. Pulling off his cap, he ran his fingers through his hair. ‘It’s been earmarked for special training. That’s all I know, and even if I did know more I couldn’t tell you. One thing I do know, though, we only have a few weeks to get the place ready before the first batch of Tommies arrive, so me and the lads are going to have to get our skates on.’

‘Which means that I, too, will have to get my skates on. I would not wish to be responsible for delaying the British army,’ Flora said, trying not to panic. Outside, the soldiers were playing an impromptu game of football on the croquet lawn. She prayed her mother had for once done as she was bid, and kept to the Lodge. ‘How many of you are here as the—what is it, advance guard?’

‘Just the one section, me and twelve men.’

‘Goodness, when you arrived it seemed like hundreds.’

‘It most likely will be soon, but for now it’s just us. And the colonel, of course, whenever he deigns to join us.’

Flora eyed him sharply. ‘You sound positively insubordinate, Corporal.’

‘Do I?’

‘The colonel strikes me as the kind of man who is rather more efficient in his absence than his presence,’ she ventured.

‘And you are qualified to make such a judgement, are you?’

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake, why must you be so abrasive?’ Flora snapped. Though he raised his brows at her flare of temper, he made no attempt to apologise. She suspected he was the kind of man who made a point of not apologising for anything, if he could avoid it. ‘Look, the truth is, I have no idea whatsoever what it is that you expect of me,’ she said with a sigh. ‘So if you can bring yourself to let me in on your plans, I would very much appreciate it.’

His expression softened into a hint of a smile, which did very strange things to Flora’s insides. ‘Since I’ve only just been dumped with— Since I’ve only just assumed responsibility, I don’t actually have any plans. You’re not the only one who is in uncharted territory.’

‘Thank you. I know that shouldn’t make me feel better, but it does.’

‘As long as you don’t go bleating to your daddy.’

‘I am not a lamb, Corporal,’ Flora snapped, ‘and I am certainly not in the habit of telling tales.’

‘I apologise, that was uncalled for.’

She glared at him. ‘Yes, it was.’

Once again, he surprised her by laughing. ‘You really are a feisty thing, aren’t you, Miss Carmichael.’

And he really was rather sinfully attractive when he let down his guard. ‘Call me Flora. We shall sink or swim together, then,’ she said, holding out her hand.

He did not shake it, but instead clicked his heels together and bowed. ‘If we are to swim together, then you must call me Geraint.’

He held her gaze as he turned her hand over and pressed a kiss to her palm, teasing her, daring her to react. His kiss made her pulse race. Seemingly as shocked as she, he dropped her hand as if he had been jolted by an electric current.

They stared at each other in silence. He was the first to look away. ‘We should start by making the tour, and take things from there,’ he said gruffly.

Had she imagined the spark between them, or was the corporal intent on ignoring it? Flora was so confused that she was happy to go along with him. ‘Yes,’ she said, aware that she was nodding rather too frantically. ‘That sounds like a plan.’

‘In the meantime, my men will unload the trucks and set up temporary camp.’

‘Oh, please, not on the lawn. My mother specifically asked...’

‘What, is she worried that we’ll dig latrines next to her rose beds?’

‘Actually, manure is very good for roses.’

She caught his eye, forcing a smile from him that relieved the tension. ‘Perhaps you could suggest somewhere more suitable, Miss Flora.’

‘At the back near the kitchens might be best. The house will shelter the tents from the wind coming in off the loch, and they will be near a good water supply.’

‘Practical thinking. I’m impressed.’

‘Goodness, a compliment Corporal—Geraint.’

‘A statement of fact.’

‘Did I pronounce it correctly? Your name, I mean. Geraint.’

‘Perfectly,’ he said shortly.

Really, his mood swung like a pendulum. ‘What have I said to offend you this time? I can almost see your hackles rising,’ Flora said, exasperated.

‘Nothing.’

She threw him a sceptical look.

‘I don’t think I’ve heard my Christian name spoken since I joined up, that’s all,’ he finally admitted. ‘I’d almost forgotten how it sounded.’

She was instantly remorseful. ‘But don’t you get leave? I am sorry, I am afraid I know nothing of these things.’

Geraint shrugged. ‘Why should you? No, we don’t get leave. Leastways, nothing long enough for me to go back to see my family.’

‘Your family! So you’re married,’ Flora exclaimed, inexplicably appalled by this.

‘Good God, no! I wasn’t married when the balloon went up and I’d be a fool to get hitched while there’s a war on. Even if there happened to be someone I wanted to marry, which there is not,’ Geraint said. ‘I meant my parents, my brother and sisters.’

‘Yes, of course you did,’ Flora said. ‘I knew that.’ Which she had, truly, for she also knew instinctively he was not the kind of man to flirt with another woman if he was married. Not that he had flirted with her. Had he? She sighed inwardly, wishing that she was not such an innocent. ‘You must miss them,’ she said, trying to pull her thoughts together. ‘Your family, I mean.’

But Geraint merely shrugged, his face shuttered. ‘We didn’t see much of each other this last while, frankly,’ he said, and when she would have questioned him further, turned his attention elsewhere. ‘I must go and see to the men, else they will happily kick a ball about all day. I’ll see you in a couple of hours.’

Which was definitely not something she should be looking forward to, Flora thought, watching him stride off purposefully.

The men were lined up on the driveway now. She could not hear what the corporal was saying to them. He seemed not to be the kind who barked orders, but rather spoke with a natural, quiet authority that made the troops pay attention. Once dismissed, they started to pull back the tarpaulins on the trucks, revealing iron bedsteads, tents, trestle tables and a host of other equipment including what looked horribly like field guns. Flora headed back to the Lodge. It had been an extremely eventful day already, and it was only lunchtime.

Chapter Three

Three days later, Geraint was in the morning room with Flora, where a phonograph sat incongruously on an antique marble-topped table. Like the rest of the house, the room was a mixture of styles, reflecting the changing tastes of the Carmichaels through the generations. Glen Massan House was too eclectic to be aesthetically pleasing. It was not a showpiece, but a home. Flora Carmichael’s home. Which it was now his duty to pillage.

He must not allow himself to think about it in that manner. She and her ilk neither deserved nor required his sympathy, yet he found it increasingly difficult to think of Flora as belonging to any clique. She seemed slightly out of place, a misfit. A bit like himself, if truth be told. ‘I can’t quite work you out,’ Geraint said, surrendering to the unusual desire to share his thoughts.

Flora looked up from her notebook, her smile quirky. ‘I thought you had me neatly labelled from the minute we met.’

‘That’s what I mean. You should be empty-headed, or your head should be stuffed full of fripperies—dresses and dances and tennis parties. I’m not even an officer. You should be looking down that aristocratic little nose at the likes of me.’

‘The likes of you?’

She eyed him deliberately up and down. If anyone else had appraised him so brazenly, it would have provoked a caustic riposte. Instead, Flora, with her sensuous mouth and her saucy look, made him want to kiss her.

‘I am not in the habit of categorising people, as you are,’ she said. ‘In any event, I very much doubt there is anyone quite like you. Which is why, despite myself, I find your company stimulating.’

Stimulating! She certainly was. ‘Then that makes two of us,’ Geraint said, trying not to smile, ‘though let me tell you, it is entirely against my principles.’

Flora gave a gurgle of laughter. ‘You are the master of the backhanded compliment. I am sorry that you find you cannot dislike me when you have tried so hard to do so.’

‘You sound as if you wish me to try harder,’ he retorted.

‘Perhaps I do. Your barbs, Corporal Cassell, have been a welcome distraction while we dismantle my home.’

Which was the nearest she had come to saying what she felt about the requisition. Her father wasn’t the only one with a stiff upper lip. Guessing that sympathy would be most unwelcome, Geraint gave a mocking bow. ‘I am delighted to have been of service.’

Flora’s smile wobbled. ‘It is silly of me, but I feel as if we are doing something very final. I doubt things will return to what they were, even when this war is over.’

‘I sincerely hope they do not.’

She sighed. ‘No, of course you don’t, and you’re probably right.’

The perfume she wore had a floral scent. Not cloyingly sweet, but something lighter, more delicate and springlike. ‘I don’t understand you,’ Geraint said. ‘You’re not some empty-headed social butterfly. Don’t you feel suffocated, stuck here in this draughty castle with nothing to do but—what, arrange flowers and sew samplers?’

‘Do not forget my playing Lady Bountiful for the poor of the parish,’ Flora snapped. ‘Then there is the endless round of parties and dances, the occasional ceilidh in the village that I must grace with my presence. Added to that, there is tennis in the summer and...’

‘It was not my intention to patronise you,’ Geraint interrupted. ‘You just baffle me.’

‘So you said.’

Her eyes were over-bright. Annoyed, as much for having allowed himself to notice the soft swell of her bosom as she folded her hands defensively across her chest as for having been the cause of the action, Geraint spoke in a gentler tone. ‘It just seems to me that you’re wasting your life, shut away here. Aren’t you bored? Why don’t you leave?’

She stared at him blankly. ‘I cannot just leave. Where would I go? What would I do?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said impatiently. ‘What do you want to do? You must have thought about it.’

‘I have never had to,’ Flora said, looking troubled, ‘which is a shocking thing to admit, but the truth, for it is not as if I spend my days idly, is that there is always something to do here. I suppose it has always been assumed that I would marry well.’

‘You mean replace your father’s patronage with that of another wealthy man so that you can carry on arranging flowers ad nauseam.’

‘That is a very cynical way of looking at matrimony,’ Flora said coldly, ‘and quite beside the point, since I have no intention of making such a match. The problem is, I am not actually qualified to do anything else. Thank you very much for bringing that fact to my attention, incidentally.’

‘You are making a pretty good fist of managing this requisition, despite your claim that you had no idea how to tackle it,’ Geraint pointed out.

‘That is because I have had your expert lead to follow.’

He shook his head firmly. ‘Do not underestimate yourself.’

‘I doubt that is possible.’

‘Flora, I meant it. You are bright, quick-witted, practical and articulate. You’ve a talent for organising, for creating order.’

‘Do you really think so?’ She spoke eagerly.

‘I wouldn’t have said it otherwise,’ Geraint replied, touched by the vulnerability her question revealed. ‘You should know me well enough by now to know I don’t say anything I don’t mean.’

‘My parents are both fairly certain that I will make a hash of things.’

‘Then you shall surprise them by proving them wrong.’

He was rewarded with a smile. ‘Perhaps I shall surprise you, too, at the end of it,’ she said. ‘Despite the melancholy nature of our task, I have to admit that I am enjoying the challenge. Perhaps I should reconsider joining the VADs, like Sheila.’

‘Sheila? You mean the maid? Blonde, pretty girl?’

‘Do you think she’s pretty?’

Geraint laughed. ‘I think that’s the first predictable thing you’ve ever said to me. Yes, she’s very pretty and I’d have to be blind not to have noticed.’

‘We went to school in the village together until I was removed to an academy for young ladies,’ Flora said, making a face. ‘Sheila is counting the days, waiting to be assigned to a hospital. I shall miss her terribly when she goes. I did consider volunteering, but my mother was appalled. She thinks it would be most improper work for me, and my father thinks that I would find it far too taxing, and the demoralising fact is that he is probably right.’ She held up her hands for his inspection. ‘Lily-white and quite unsullied by hard work, as I am sure you have noted.’

Which so exactly mirrored his own, original opinion of her that Geraint felt a stab of guilt. ‘There are plenty of other things you could do, I’m sure,’ he said gruffly.

‘Would that I had your confidence in me. Which sounds really rather pathetic. You are right, I am stuck in a rut and have no purpose whatsoever in my life save to look decorative while waiting for a suitable husband to appear,’ Flora replied brightly. ‘Thank you, as I said earlier, for pointing that out, but if you don’t mind, I have had quite enough picking over my empty life and my character flaws for one day.’ She picked up her notebook and pencil. ‘I think we should get back to work.’

Her smile was fixed, her cheeks flushed, though she countered his scrutiny with a determined tilt of her chin. Geraint was not fooled, but he was not such an idiot as to ignore the signs. No trespassing. He ought to be pleased with himself for making her face up to some unpalatable truths, but he wasn’t. She had taken his criticisms on the chin, too. She would have been within her rights to tell him to mind his own business, which was what he would have said had the roles been reversed. Flora Carmichael might look as if a puff of wind would blow her away, but she had backbone. He had to admire her for that. In fact, the more he got to know her, the more he liked her....

The realisation set him quite off-kilter. Geraint got to his feet and made a point of consulting his wristwatch. A gift from his parents on his twenty-first birthday, it was a plain, functional timepiece, but it was one of his most precious possessions. ‘You carry on without me. I need to check on the lads.’

* * *

The door closed behind him, but Flora remained where she was. Geraint did not, as Robbie would say, pull his punches. It was a dispiriting thought, but she suspected she had been merely marking time with her life without even realising it. Forcing herself to think about it now, the very idea of turning into her mother, which she would, if she continued to allow herself to drift with the tide, made her shudder. Her parents expected so little from her that it was ridiculously easy to please them. And it would, sadly, be ridiculously easy to disappoint them, were she to pursue some sort of independent course.

‘Whatever that may be,’ Flora muttered to herself. Pacing over to the window, she stared morosely out at the loch. The problem was that now Geraint had pointed it out, she could not deny the creeping dissatisfaction she had been feeling, and nor could she ignore it, though to do something about it would be to fly in the face of her parents’ expectations. ‘So I am damned if I do, and damned if I don’t,’ she said wryly. ‘Which brings me no nearer at all to knowing what it is I am going to do.’

You are bright, quick-witted, practical and articulate, Geraint had said. None of those epithets had ever been applied to her before, yet Geraint never said what he didn’t believe. He was blunt to a fault, but he also saw things in her that others did not, and expected much more of her than anyone else did, which both pleased and scared her a little. What if she failed?

Think positively, Flora castigated herself. She would not fail, because that would reflect badly on Geraint, and she wanted Geraint to succeed. Almost more than she wanted to succeed herself. Which was a novel, not to say startling, thought. ‘Sink or swim,’ Flora repeated, remembering the pact they had made.