Полная версия

Полная версияLife of John Sterling

And yet, as I said before, it may be questioned whether piety, what we call devotion or worship, was the principle deepest in him. In spite of his Coleridge discipleship, and his once headlong operations following thereon, I used to judge that his piety was prompt and pure rather than great or intense; that, on the whole, religious devotion was not the deepest element of him. His reverence was ardent and just, ever ready for the thing or man that deserved revering, or seemed to deserve it: but he was of too joyful, light and hoping a nature to go to the depths of that feeling, much more to dwell perennially in it. He had no fear in his composition; terror and awe did not blend with his respect of anything. In no scene or epoch could he have been a Church Saint, a fanatic enthusiast, or have worn out his life in passive martyrdom, sitting patient in his grim coal-mine, looking at the "three ells" of Heaven high overhead there. In sorrow he would not dwell; all sorrow he swiftly subdued, and shook away from him. How could you have made an Indian Fakir of the Greek Apollo, "whose bright eye lends brightness, and never yet saw a shadow"?—I should say, not religious reverence, rather artistic admiration was the essential character of him: a fact connected with all other facts in the physiognomy of his life and self, and giving a tragic enough character to much of the history he had among us.

Poor Sterling, he was by nature appointed for a Poet, then,—a Poet after his sort, or recognizer and delineator of the Beautiful; and not for a Priest at all? Striving towards the sunny heights, out of such a level and through such an element as ours in these days is, he had strange aberrations appointed him, and painful wanderings amid the miserable gaslights, bog-fires, dancing meteors and putrid phosphorescences which form the guidance of a young human soul at present! Not till after trying all manner of sublimely illuminated places, and finding that the basis of them was putridity, artificial gas and quaking bog, did he, when his strength was all done, discover his true sacred hill, and passionately climb thither while life was fast ebbing!—A tragic history, as all histories are; yet a gallant, brave and noble one, as not many are. It is what, to a radiant son of the Muses, and bright messenger of the harmonious Wisdoms, this poor world—if he himself have not strength enough, and inertia enough, and amid his harmonious eloquences silence enough—has provided at present. Many a high-striving, too hasty soul, seeking guidance towards eternal excellence from the official Black-artists, and successful Professors of political, ecclesiastical, philosophical, commercial, general and particular Legerdemain, will recognize his own history in this image of a fellow-pilgrim's.

Over-haste was Sterling's continual fault; over-haste, and want of the due strength,—alas, mere want of the due inertia chiefly; which is so common a gift for most part; and proves so inexorably needful withal! But he was good and generous and true; joyful where there was joy, patient and silent where endurance was required of him; shook innumerable sorrows, and thick-crowding forms of pain, gallantly away from him; fared frankly forward, and with scrupulous care to tread on no one's toes. True, above all, one may call him; a man of perfect veracity in thought, word and deed. Integrity towards all men,—nay integrity had ripened with him into chivalrous generosity; there was no guile or baseness anywhere found in him. Transparent as crystal; he could not hide anything sinister, if such there had been to hide. A more perfectly transparent soul I have never known. It was beautiful, to read all those interior movements; the little shades of affectations, ostentations; transient spurts of anger, which never grew to the length of settled spleen: all so naive, so childlike, the very faults grew beautiful to you.

And so he played his part among us, and has now ended it: in this first half of the Nineteenth Century, such was the shape of human destinies the world and he made out between them. He sleeps now, in the little burying-ground of Bonchurch; bright, ever-young in the memory of others that must grow old; and was honorably released from his toils before the hottest of the day.

All that remains, in palpable shape, of John Sterling's activities in this world are those Two poor Volumes; scattered fragments gathered from the general waste of forgotten ephemera by the piety of a friend: an inconsiderable memorial; not pretending to have achieved greatness; only disclosing, mournfully, to the more observant, that a promise of greatness was there. Like other such lives, like all lives, this is a tragedy; high hopes, noble efforts; under thickening difficulties and impediments, ever-new nobleness of valiant effort;—and the result death, with conquests by no means corresponding. A life which cannot challenge the world's attention; yet which does modestly solicit it, and perhaps on clear study will be found to reward it.

On good evidence let the world understand that here was a remarkable soul born into it; who, more than others, sensible to its influences, took intensely into him such tint and shape of feature as the world had to offer there and then; fashioning himself eagerly by whatsoever of noble presented itself; participating ardently in the world's battle, and suffering deeply in its bewilderments;—whose Life-pilgrimage accordingly is an emblem, unusually significant, of the world's own during those years of his. A man of infinite susceptivity; who caught everywhere, more than others, the color of the element he lived in, the infection of all that was or appeared honorable, beautiful and manful in the tendencies of his Time;—whose history therefore is, beyond others, emblematic of that of his Time.

In Sterling's Writings and Actions, were they capable of being well read, we consider that there is for all true hearts, and especially for young noble seekers, and strivers towards what is highest, a mirror in which some shadow of themselves and of their immeasurably complex arena will profitably present itself. Here also is one encompassed and struggling even as they now are. This man also had said to himself, not in mere Catechism-words, but with all his instincts, and the question thrilled in every nerve of him, and pulsed in every drop of his blood: "What is the chief end of man? Behold, I too would live and work as beseems a denizen of this Universe, a child of the Highest God. By what means is a noble life still possible for me here? Ye Heavens and thou Earth, oh, how?"—The history of this long-continued prayer and endeavor, lasting in various figures for near forty years, may now and for some time coming have something to say to men!

Nay, what of men or of the world? Here, visible to myself, for some while, was a brilliant human presence, distinguishable, honorable and lovable amid the dim common populations; among the million little beautiful, once more a beautiful human soul: whom I, among others, recognized and lovingly walked with, while the years and the hours were. Sitting now by his tomb in thoughtful mood, the new times bring a new duty for me. "Why write the Life of Sterling?" I imagine I had a commission higher than the world's, the dictate of Nature herself, to do what is now done. Sic prosit.

1

John Sterling's Essays and Tales, with Life by Archdeacon Hare. Parker; London, 1848.

2

Commons Journals, iv. 15 (l0th January, 1644-5); and again v. 307 &c., 498 (18th September, 1647-15th March, 1647-8).

3

Literary Chronicle, New Series; London, Saturday, 21 June, 1828, Art. II.

4

"The Letters of Vetus from March 10th to May 10th, 1812" (second edition, London, 1812): Ditto, "Part III., with a Preface and Notes" (ibid. 1814).

5

Here, in a Note, is the tragic little Register, with what indications for us may lie in it:—

(l.) Robert Sterling died, 4th June, 1815, at Queen Square, in his fourth year (John being now nine).

(2.) Elizabeth died, 12th March, 1818, at Blackfriars Road, in her second year.

(3.) Edward, 30th March, 1818 (same place, same month and year), in his ninth.

(4.) Hester, 21st July, 1818 (three months later), at Blackheath, in her eleventh.

(5.) Catherine Hester Elizabeth, 16th January, 1821, in Seymour Street.

6

History of the English Universities. (Translated from the German.)

7

Mrs. Anthony Sterling, very lately Miss Charlotte Baird.

8

Biography, by Hare, pp. xvi-xxvi.

9

Biography, by Mr. Hare, p. xli.

10

Hare, pp. xliii-xlvi.

11

Hare, xlviii, liv, lv.

12

Hare, p. lvi.

13

P. lxxviii.

14

Given in Hare (ii. 188-193).

15

Came out, as will soon appear, in Blackwood (February, 1838).

16

"Hotel de l'Europe, Berlin," added in Mrs. Sterling's hand.

17

Hare, ii. 96-167.

18

Ib. i. 129, 188.

19

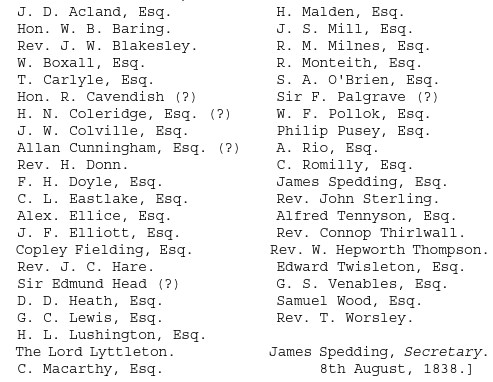

Here in a Note they are, if they can be important to anybody. The marks of interrogation, attached to some Names as not yet consulted or otherwise questionable, are in the Secretary's hand:—

20

Hare, p. cxviii.

21

Of Sterling himself, I suppose.

22

Hare, ii. p. 252.

23

Poems by John Sterling. London (Moxon), 1839.

24

The Election: a Poem, in Seven Books. London, Murray, 1841.

25

Pp. 7, 8.

26

Pp. 89-93.

27

Sister of Mrs. Strachey and Mrs. Buller: Sir John Louis was now in a high Naval post at Malta.

28

Long Letter to his Father: Naples, 3d May, 1842.

29

Death of her Mother, four mouths before. (Note of 1870.)