Полная версия:

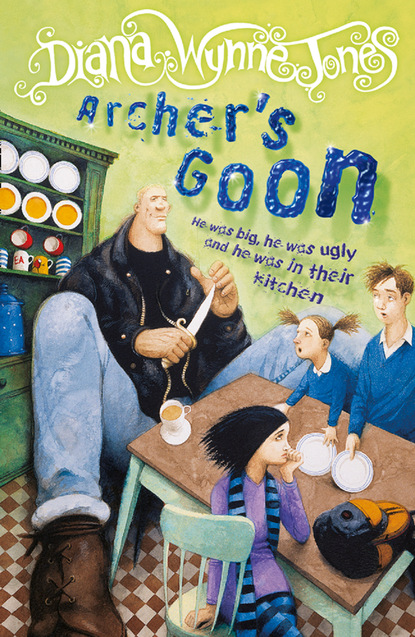

Archer’s Goon

The smile was sincere, and the voice such a friendly, soothing rumble that Howard felt thoroughly ashamed of asking. He turned to go away.

“Not true,” the Goon remarked pleasantly.

Mr Mountjoy gave the Goon an alarmed, fleeting look. “But it is. Quentin Sykes hadn’t been able to write anything for nearly a year after his second book came out. I liked the book and I was sorry for the man, so I hit on a way to get him going again. It’s a sort of joke between us by now.”

“Not true,” the Goon remarked, less pleasantly and more firmly.

That changed Howard’s mind. “No, I don’t think it is,” he said. “If it’s a joke, why did you stop all the water and electricity in our house one time when he didn’t do the words?”

“That had nothing to do with me,” Mr Mountjoy said sincerely. “It may well have been a complete coincidence. If it was my superior – and I admit I have a superior – then he told me nothing about it at all.”

“Was it Archer who did it?” asked Howard.

Mr Mountjoy shrugged and spread his plumpish hands towards Howard, to show he knew nothing about that either. “Who knows? I don’t.”

“And what does Archer do with the words?” said Howard. “Who is Archer anyway? Lord Mayor or something?”

Mr Mountjoy laughed, shook his head and began spreading his hands again, to show he really did not know anything. But before his hands were half-spread, the Goon’s enormous hand came down from behind Howard’s shoulder. It landed across Mr Mountjoy’s gesturing hands and trapped both of them down on Mr Mountjoy’s desk.

“Tell him,” said the Goon.

Mr Mountjoy pulled at his hands, but like Awful before him, he found that made no impression on the Goon at all. He became hurt and astonished. “Really! My dear sir! Please let me go.”

“Talk,” said the Goon.

“I deplore your choice of friends,” Mr Mountjoy said to Howard. “Does your father know the company you keep?”

The Goon looked bored. “Have to stay here all night,” he said to Howard. He propped himself on the fist that was holding down Mr Mountjoy’s hands and yawned.

Mr Mountjoy gave a strangled squeak and struggled a little. “Let go! You’re squashing my hands, and I’ll have you know I’m a keen pianist!” His voice was nearly a yelp. “All right. I’ll tell you the little bit I know! But you’re to let go first!”

The Goon unpropped himself. “Can always do it again,” he told Howard reassuringly.

Mr Mountjoy rubbed his hands together and felt each of his fingers, morbidly, as if he had thought one or two might be missing. “I’ve no idea what Archer wants with the blessed words!” he said peevishly. “I don’t even know if it’s Archer I send them to. All I’ve ever heard is his voice on the telephone. It could be any of them.”

“Any of who?” Howard said, mystified.

“Any of the seven people who really run this town,” said Mr Mountjoy. “Archer’s one. The others are Dillian, Venturus, Torquil, Erskine and – what are their names? Oh, yes. Hathaway and Shine. They’re all brothers.”

“How do you know?” demanded the Goon.

“I made it my business to find out,” Mr Mountjoy said. “Wouldn’t you, if one of them made you do something this peculiar for them?”

“Shouldn’t have done,” said the Goon. “Won’t like that. Know. Working for Archer.”

“Then what are you doing here?” Mr Mountjoy said. “I concede that you may not have much brain. You don’t appear to have room for one. But this is an odd place to be if I work for Archer, too.”

“Doing him a favour,” said the Goon, pointing a parsnip-sized thumb at Howard. He said to Howard, “Know I’m your friend now. Want to know any more?”

“Um – yes,” said Howard. “How does he send the words to whoever it is?”

“I address them to a post office box number and send a typist out to post them,” said Mr Mountjoy. “I really know nothing more. I have tried to find out who collects them, and I have failed.”

“So you don’t know how this last lot went missing?” said Howard.

“It never reached me,” said Mr Mountjoy. “Now do you mind taking your large friend and going away? I have work to do.”

“Pleasure,” said the Goon. He put both hands on the desk and leaned towards Mr Mountjoy. “Tell us the back way out.”

“I bear you no malice,” Mr Mountjoy said hastily. “The door at the end. Marked ‘Emergency Stairs’.” He picked up a folder labelled ‘Centre development: Polytechnic’ and pretended to be very busy reading it.

The Goon jerked his head at Howard in the way Howard was now used to and progressed out into the offices again. Heads lifted from typewriters and frozen faces watched them as they progressed right down to the end of the rooms. Here, sure enough, was a door with wire mesh set into the glass of it. ‘Fire Door,’ it said in red letters, ‘Emergency Stairs.’ The Goon slung it open, and they went out on to a long flight of concrete stairs.

The Goon raced down these stairs surprisingly quickly and quietly. Howard’s knees trembled rather as he followed. He was scared now. They kept galloping down past other wire-and-glass doors, and some of these were bumping open and shut. Howard could see the dark shapes of people milling about behind them, and at least twice he heard some of the things they said. “Walked straight through the highway board!” a woman said behind the first. Lower down, someone was calling out, “They went up that way, Officer!” Howard put his head down and bounded two stairs at a time to keep up with the Goon. Scared as he was, he was rather impressed. The Goon certainly got results.

At the bottom of the stairs a heavy swing door let them out into a back yard crowded with gigantic rubbish bins on wheels. Here Howard, as he threaded his way after the Goon, remembered to his annoyance that he had forgotten to ask Mr Mountjoy how Archer – or whichever brother it was – had first got hold of Mr Mountjoy and made him work for him. But it was clearly too late to go back and ask that now.

The yard led to a car park and the car park led to a side street. At the main road the Goon stuck his head round the corner and looked towards the front of the Town Hall, about fifty yards away. Three police cars were parked beside the steps with their lights flashing and their doors open. The Goon grinned and turned the other way. “Dillian nearly got us,” he remarked.

“Dillian?” asked Howard, trotting to keep up.

“Dillian farms law and order,” said the Goon.

“Oh,” said Howard. “Let’s go and see Archer now.”

But the Goon said, “Got to see your dad about the words,” and Howard found himself hurrying towards home instead. When the Goon decided to go anywhere, he set that way like a strong current, and there seemed nothing Howard could do about it.

Five minutes later Howard and the Goon turned right past the corner shop into Upper Park Street. Howard was rather glad to see it. He liked the rows of tall, comfortable houses and the big tree outside Number 8. He was even glad to see the hopscotch that Awful and her friends kept chalking on the pavement – when Awful was not quarrelling with those friends, that was. But the thing which made him gladdest of all was to see his own house – Number 10 – without a police car standing outside it. He had been dreading that. Mr Mountjoy had only to say who Howard’s father was.

Dad was in the kitchen with Fifi and Awful, eating peanut butter sandwiches. All their faces fixed in dismay as the Goon ducked his little head and came through the back door after Howard.

Quentin said, “Not again!” and Fifi said, “The Goon returns. Mr Sykes, he haunts us!”

Awful glowered. “It’s all Howard’s fault,” she said.

“What’s that noise?” said the Goon.

It was the drums, throbbing gently from under the mound of blankets in the hall. Quentin sighed. “They’ve been doing that all day.”

“Fix them,” said the Goon, and progressed through the kitchen into the hall. Howard paused to take a peanut butter sandwich, so he was too late to see what the Goon did to the drums. By the time he got there the blankets had been tossed aside and the Goon was standing with his fists on his hips, staring at the slack and silent drums oozing socks and handkerchiefs. He grinned at Howard. “Torquil,” he said.

“Torquil what?” asked Howard.

“Did that,” said the Goon, and marched back to the kitchen. There he stood and stared at Quentin the same way he had stared at the drums.

“Don’t tell me,” said Quentin. “Let me guess. Archer is not satisfied. He has counted the words and found there were only one thousand and ninety-nine.”

The Goon shook his head, grinning as usual. “Two thousand and four,” he said.

“Well, I thought I’d better end the last sentence,” Quentin said. “Mountjoy never insisted on an exact number.”

The Goon said, “Mountjoy must have told you something else then.” He dived a hand into the front of his leather jacket and brought out the four typed pages, now grey and used-looking and bent. He thrust them at Quentin at the end of a yard or so of arm. “Take a look. What’s wrong?”

Quentin took the pages and unfolded them. He separated them one from another, enough to glance at each. “This seems all right. My usual drivel. Old ladies riot in Corn Street. I couldn’t remember quite what I put in the lot Archer never got, but this is the gist—” He stopped as he realised. “Oh,” he said glumly. “It’s supposed not to be anything I’ve done before. But how the devil did Archer know?”

He looked up at the Goon. The Goon’s head nodded, so fast that it almost jittered. The daft grin spread on his face. He looked so irritating that Howard was not surprised when Quentin exploded. “Damn it!” Quentin shouted. He hurled the papers into the bread and peanut butter. “I’ve already done the words for this quarter! How can I help it if some fool in the Town Hall loses it? Why should I bother my brains for more nonsense just because you and Archer say so? Why should I put up with being bullied in my own house?”

He raged for some time. His face grew red and his hair flew. Fifi was frightened. She sat staring at Quentin with both hands to her mouth, pressed back in her chair as far away from him as possible. The Goon grinned and so did Awful, who loved Quentin raging. Howard lifted up the typewritten papers and helped himself to more bread and peanut butter while he waited for his father to finish.

“And I don’t care if I never write Archer another word!” Quentin finished. “That’s final.”

“Go on,” said Awful. “Your paunch bounces when you shout!”

“My lips are now sealed,” said Quentin. “Probably forever. My paunch may never bounce again.”

Fifi gave a feeble giggle at this, and the Goon said, “Archer wants a new two thousand.”

“Well, he won’t get it,” Quentin said. He folded his arms over his paunch and stared at the Goon.

The Goon returned the stare. “Stay here till you do it,” he observed.

“Then you’d better get yourself a camp bed and a change of clothes,” said Quentin. “You’ll be here for good. I’m not doing it.”

“Why not?” said the Goon.

Quentin ground his teeth. Everyone heard them grate. But he said quite calmly, “Perhaps you didn’t grasp what I’ve just been saying. I object to being pushed around. And I’ve got a new book coming on.” Howard and Awful both groaned at this.

Quentin looked at them coldly. “How else,” he said, “shall I earn your bread and peanut butter?”

“You look through me and fuss about noise when you’re writing a book,” Howard explained.

“And you go all grumpy and dreamy and forget to go shopping,” said Awful.

“You must learn to live with it,” said their father. “And with the Goon, too, by the looks of things, since I am going to write that book whatever he does.” And he looked at the Goon challengingly.

The Goon’s answer was to go over to the chair where they had first seen him and sit in it. He extended his great legs with the huge boots on the end of them, and the kitchen was immediately full of him. He fetched out his knife and began cleaning his nails. It was hard to believe he had ever moved.

“Make yourself quite at home,” Quentin said to him. “As the years pass, we shall all get used to you.” An idea struck him and he turned to Fifi. “Do you think people can claim tax relief for a resident Goon?”

Fifi was backing into the hall, signalling to Howard to come, too. “I don’t know,” she said helplessly. Howard and Awful followed her, wondering what was the matter. They found her backing into the front room.

“This is terrible,” Fifi whispered. She looked really upset. “It’s all my fault. I was busy when your dad gave me those words to take to the Town Hall, so I gave them to Maisie Potter to take because she was going that way.”

“Then you’d better get hold of Miss Potter,” said Howard, “or we’ll have the Goon for good.”

“Perhaps Miss Potter stole them,” said Awful. It was automatic with Awful to turn the television on whenever she came into the front room. She did it now. When the picture came on, she sprang back with one of her most piercing yells. “Look, look, look!”

Howard and Fifi looked. Instead of a picture on the screen, there were four white words on a black background. They said: ARCHER IS WATCHING YOU. It seemed as if Archer was backing the Goon up.

Fifi uttered a wail of guilt and fled to the hall, where she stood astride the drums and phoned the Poly in a whisper, so that Quentin should not hear. But the Poly had closed for the night by then. Fifi tried telephoning Miss Potter at home then, but Miss Potter was out. Miss Potter went on being out. Fifi spent the rest of the evening sneaking into the hall to stand astride the drums and dial Miss Potter’s number, but Miss Potter kept on being out. Awful meanwhile turned the television on and off and switched from channel to channel. No matter what she did, the only thing the screen showed were those four words: ARCHER IS WATCHING YOU. In the kitchen Quentin sat with his arms folded, staring obstinately at the Goon. And the Goon sat attending to his nails and filling the floor with leg.

Catriona came in quite soon after that. She was not tired that day. She stood in the doorway with an armful of sheet music and said, “Where’s Awful? I can’t hear the television. And who’s breathing so heavily?… Oh, it’s you, Quentin!” The scratching of knife on nail caused her head to turn and her eyes to travel up yards of leg to the Goon’s little face. “Why have you come back?”

The Goon grinned. Quentin snapped, “He grows here. I think he’s a form of dry rot.”

“Then he can make himself useful,” Catriona said. She gave the Goon the kind, firm, unavoidable look that seemed to work so well on him. “Take this music up to the landing for me, and then come down and help me get supper. Oh, and do you play the piano?”

The Goon shook his head earnestly. He looked really alarmed.

“What a pity,” said Catriona. “Everyone should learn the piano. I wanted you to help Awful practise. Howard, why aren’t you doing your violin practice? Hurry up, both of you.”

As Howard and the Goon both leaped to their feet, Quentin said, “You’ve forgotten me. You haven’t asked why I’m not doing anything.”

“I know about you,” Catriona said. “I can see that you’re refusing to write another two thousand words. You should have done that thirteen years ago. Hurry up, Howard!”

Howard went gloomily to look for his violin. That was the bother with Mum not being tired. He and Awful both had to practise. Dad always politely allowed them to forget. He opened the cupboard under the stairs where his violin probably was and found the Goon tiptoeing gigantically after him, looking woebegone.

“Don’t know how to cook,” the Goon said.

“She’ll tell you how,” Howard said heartlessly. “She’s in her good mood.”

The Goon’s round eyes popped. “Good mood?”

Howard nodded. “Good mood.” The Goon’s way of talking was catching. He dragged his violin out from under a heap of Wellington boots and took it away upstairs, feeling really hopeful. An hour or so of Mum in her good mood might persuade even the Goon to leave.

Howard was not much good at playing the violin, but he was good at getting practice done. He set his alarm clock for twenty minutes later and spent four of the minutes sort of tuning strings. Then he put the violin under his chin and disconnected his mind. He let the bow rasp and wail, while he designed a totally new spaceship for carrying heavy goods, articulated so that it could thread its way among asteroids and powered by a revolutionary FTL drive.

That did not take long, so he spent another few minutes looking at himself in the mirror as he played, trying to see himself as the pilot of that spaceship. Although he was so tall, his face was annoyingly round and boyish. But the violin at least gave him several manly chins – though not as many as Dad had – and he thought that now that he had grown his straight tawnyish hair into a long fringe, his eyes stared out keenly beneath it. He could almost imagine those eyes playing over banks of instruments and dials or gazing out on hitherto unknown suns.

After ten minutes he was able to stop playing. Mum had told Awful to do her piano practice. Howard knew from experience that the resulting screams drowned everything else. He listened and from time to time drew the bow across the strings – so that he could truthfully say he had been playing the whole time – and felt more hopeful than ever. The Goon had proved sensitive to noise from Awful. Surely he would not be able to stand much more?

Finally, Awful’s screams died away to a sultry sobbing. Howard scribbled the bow about for another half minute. Then his alarm went off and he was able to go downstairs. He passed Fifi dialling Miss Potter again in the hall. In the kitchen Quentin was still sitting, still looking obstinate. Awful was lying on the floor, gulping, “Shan’t practise. Won’t practise. Want television. I shall die and then you’ll be sorry!” And the Goon, far from being driven away, was at the sink, laboriously carving potatoes down to the size of marbles and sweating with the effort.

“Very good!” Catriona told the Goon kindly.

“Now just peel the peel, and we might have enough to eat,” Howard said. The Goon gave him a wondering stare.

“Don’t tax his mind, Howard. He’s on overload already,” Quentin said.

“Want television!” bawled Awful.

Howard went away into the hall. It was funny, he thought, that Mum could control the Goon perfectly, yet she could never make Awful do anything at all. “Any luck?” he asked Fifi as she put down the phone.

“No,” Fifi said despairingly. “I’ll have to wait and try to catch her after the lecture tomorrow. Oh, Howard! I do feel so guilty!”

“She’s probably just forgotten you asked her to do it,” Howard said.

“She never forgets anything – not Maisie Potter!” said Fifi. “That’s why I asked her to do it. Howard, I’m afraid the Goon might stick his knife into your dad!”

“Not while Mum’s here,” said Howard. “Anyway, I don’t think Dad’s frightened of the Goon. He’s just annoyed.”

By the time supper was ready Awful had sobbed herself into the state where you feel ill. When she got like that, she could often make herself sick. She crawled under the table and made hopeful vomiting noises. She knew that would put everyone off supper anyway.

“Stop it, Awful!” everyone shouted. “Stop her, Howard!”

Howard got down on to his knees and looked into Awful’s angry, swollen face. “Do stop it,” he said. “You can have my coloured pencils if you stop.”

“Don’t want them,” said Awful. “I want to be disgustingly sick.”

The table above them lifted and sloped sharply. Howard found the Goon had got down on his knees too, half under the table. Fifi was catching knives and glasses as they slid off. “Bet you can’t be sick,” the Goon said to Awful. “Go on. Interested.”

Awful glowered at him.

“Let me try?” suggested the Goon. “Both do it. Bet I win.”

Awful’s swollen face began to look interested. She shrugged crossly. The Goon stuck his head out from under the table and looked at Quentin.

“Mind if we use the bathroom? Competition.”

The little head staring across the table looked rather as if it were on a plate. Quentin shut his eyes. “Do what you like. I don’t deserve any of this!”

“Come on,” the Goon said to Awful.

Awful scrambled out willingly. “I’m going to win,” she announced as they left.

Five minutes later they came back. Awful looked smug, and the Goon looked green. “Who won?” asked Howard.

“She did,” said the Goon. He seemed subdued and not very hungry. Awful, on the other hand, was thoroughly pleased and amiable and ate a great deal.

Howard was exasperated. If even Awful at her very worst could not send the Goon away, what would? The Goon ate the small amount he seemed able to manage with painstaking good manners and kept his feet wrapped dutifully around the back of his chair, so as not to lift the table.

And as if this were not enough, Catriona was grateful to the Goon for putting Awful in a good mood again. She began thinking of him as a proper visitor and wondering where he should sleep. “I wish we had a spare room,” she said. “But we haven’t, with Fifi here.”

Fifi and Howard were not the only ones who found this a bit much. “Get this quite clear,” Quentin said. “If he decides to stay, it’s his bad luck. He can sleep on the kitchen floor for all I care!”

“Quentin! That’s unfeeling!” said Catriona.

Howard made haste to get away again upstairs, where he barricaded himself into his room. He knew what would happen if he did not. His mother would give the Goon Howard’s room and make Howard share with Awful. And Howard was not making that sacrifice – not for the Goon! All the same, he was surprised to find, while he was wedging a chair under his doorknob, that he felt a little guilty. The Goon had helped him find Mountjoy and had made Mountjoy answer his questions. He seemed to want Howard to like him. “But I don’t like him this much!” Howard said, and made sure the chair was quite firm. Then he designed several more spaceships to take his mind off the Goon.

When he came down in the morning, he found the problem solved.

The Goon was doubled into the sofa in the front room, wrapped in the blankets that had been over the drums. The Goon had really settled in. He had moved the sofa round so that he could watch breakfast television and was basking there with a big grin on his face and a mug of tea in his hand as he watched. As Howard came in, however, the picture fizzed and vanished. Howard just caught the words ARCHER IS WATCHING YOU before the Goon’s long arm shot out and turned the television off.

“Keeps doing that,” the Goon said in an injured way.

“Perhaps Archer doesn’t trust you,” Howard said.

“Doing my best,” the Goon protested. “Staying here till your dad does the words.”

“You’re going the wrong way about it,” Howard explained. “I know Dad. You’ve got his back up by hanging around trying to bully him like this. The way to do it is to pretend to be very nice and say it doesn’t matter. Then Dad would get a bad conscience and do the words like a shot.”

“Got to do it my way,” the Goon said.

“Then don’t blame me if you’re still here next Christmas,” said Howard. The Goon grinned at that, as if he thought it was a good idea, annoying Howard considerably.

On the way to school Howard noticed that someone had chalked the name ARCHER beside Awful’s hopscotch. It was chalked on the wall of the corner shop, too, and when Howard got to school, the name ARCHER stared at him again, done in white spray paint on the wall of the labs. There was a long, boring talk about vandals in Assembly because of it.

Howard was annoyed for a while because it was Dad’s business, not his. But he forgot about it in English because he was busy making a careful, soothing drawing of his articulated spaceship.