Полная версия

Полная версияThe Little Colonel's Holidays

It was an attic-like room over the kitchen, with such a low sloping ceiling that she could touch it with her hand, except when she stood in the middle of the room. There was a rough, unpainted floor, a cot, a dry-goods box covered with newspaper, on which stood a tin basin and a broken-nosed water-pitcher. Some nails, driven along the wall, held a row of clothes, and a chair with both rockers broken off was propped against the wall. Lloyd looked around her with a shiver. The only bright spot in the room was a bunch of golden-rod in a bottle, and the only picture, a page torn from an illustrated newspaper, and pinned to the wall.

Wondering what kind of a picture such a creature as the Barley-bright witch would choose to decorate her room, Lloyd walked across to examine it. It was the front page from an old Harper's Weekly. The date caught her eye first: December 25, 1897. And then she found herself looking into a room still more pitiful than the one in which she stood, for the pictured room was part of an old New York tenement, and sobbing in the corner was a ragged, half-starved little waif, heartbroken because Santa Claus had passed her by, and she had found an empty stocking on Christmas morning.

Lloyd could not see the face hidden in the tattered apron, which the disappointed little hands held up. She could not hear the sobs that she knew were shaking the thin little shoulders, but she felt the misery of the scene as forcibly as if the real child stood before her. As she stood and looked, she knew that if all the troubles and disappointments of her whole life could be put together, they would be as only a drop compared to the grief of the poor little creature in the picture.

"Oh, Betty!" she called. "Come heah quick! I want to show you something."

The distress in Lloyd's voice made Betty hurry across the passage with her pen in her hand, wondering what could be the matter.

"Look!" exclaimed Lloyd, pointing to the picture. "How can Molly keep such a thing in her room? Do you s'pose she was evah like that? It's enough to make her cry every time she looks at it."

"Maybe she used to be like that," said Betty, examining the picture carefully, "and maybe she keeps it here to remind her how much better off she is now than she used to be."

"I can't see that her room is much nicer," said Lloyd, looking around with an expression of disgust.

"It always has been used as a sort of storeroom," explained Betty. "This is the first time I've been in here since I came back, and I didn't know how it had been fixed for Molly. Cousin Hetty hasn't any time or money to spend making it look nice. Besides, she is only in here for a little while. She is to have my room when I go away. If I'm abroad all winter, and with Joyce next summer, and at Locust going to school the year after, as godmother has planned, I suppose I'll never be back here again to really live. I'm going to make a new pincushion and a cover for my bureau, and put a white curtain at the window before I leave. Maybe it will look as fine to Molly as my white and gold room did to me at the House Beautiful. It isn't any wonder she feels jealous of us, when she hasn't a single nice thing in the whole world."

"Maybe I oughtn't to have written such spiteful things about her to Joyce," said Lloyd, whose heart began to soften and whose conscience pricked as she turned again to the picture.

But even while they were planning the changes they would make in the gable room for Molly, there was a stealthy step on the stairs, and Molly herself stood in the door, glaring at them like an angry tigress.

"How dare you!" she cried, stamping her foot in a furious rage. "How dare you come in here spying on me and making fun of my things and looking at my picture! You sha'n't look at my little Dot when she is so miserable. You sha'n't put eyes on her again!"

With a white angry face she dashed past them, tore the picture from the wall, and with it held tightly against her threw herself face downward on the cot.

"We were not spying on you," began Lloyd, indignantly. "We were not making fun of your things!"

"I know better. Get out of this room, both of you! This minute!" cried Molly, lifting her white face in which her angry eyes burned like flames. Then she buried her head in her pillow, sobbing bitterly: "If y-you were an or-orphan – and hadn't but one thing in the world, you wouldn't want p-people to come sp-spying on you, that way."

Puzzled and almost frightened at such an outburst, the girls retreated to the doorway, and then as she continued to storm at them they went back to Betty's room. They could hear her sobbing even with the door shut. Presently Betty said: "I'm going in there again, and see if I can find out what's the matter. I am an orphan, too, and maybe I can coax her to tell me, when she knows how sorry I am for her."

People wondered sometimes at Betty's way of walking into their hearts; but sympathy is an open sesame to nearly all gates, and sympathy was Betty's unfailing key. It was always ready in her loving little hand.

Presently, when Molly's wild burst of angry sobbing had subsided somewhat, Betty ventured back to her. Lloyd heard a low murmuring of voices, first Betty's and then Molly's, as one little orphan poured out her story to the other. It was nearly an hour before Betty came back to her room. Lloyd had written another letter while she waited, and now sat leaning against the window-sill, listening to the monotonous drip-drop-drip-drop from a leaky spout above the window.

"Well, what was it?" she asked, eagerly, as Betty opened the door.

"Oh, you never heard anything so pitiful," exclaimed Betty, sitting down on her bed and drawing her feet up under her comfortably before she began. "It is just like a story in a book.

"Molly says that when she was little her father was a railroad conductor, and she and her mother and grandmother and baby sister lived in a little house at the edge of town. It was near enough the railroad track for them to wave to her father, from the front door, whenever his train passed. He could come home only once a week. She and Dot thought he was the best father anybody ever had, for he never came home without something in his pockets for them, and he rode them around on his shoulders and played with them all the time he was in the house. He was always bringing things to their mother, too, a pretty cup and saucer or a pot of flowers, or something to wear; and as for the old grandmother, she spent her time telling the neighbours how good her son was to her.

"But Molly says one summer they moved away from the house by the railroad track and took a smaller one in town, where there wasn't any garden and trees, and where there wasn't even any grass, except a narrow strip in the front yard. Her father had lost his place as a conductor, and was out of work for a long time. By and by they sold their piano and the carpets and the nicest chairs. Then they moved again. This time it was to a cottage without even a strip of grass. The front door opened out on the pavement and there was no place for them to play except on the streets. Their father never brought anything home to them any more, and never played with them. They couldn't understand what made him so cross, or what made their mother cry so much, until one day she heard some of their neighbours talking.

"She and Dot were waiting in the corner grocery for a loaf of bread, and she heard one woman say to another, in a low tone, 'Those are Jim Conner's children, poor little kids. My man says he used to be one of the best conductors on the road, but he lost his job when he took to getting drunk every Saturday night. He's going down-hill now, fast as a man can go. Heaven only knows what'll become of his family if he doesn't put on the brakes soon.'

"Then Molly knew what was the matter, and she didn't make her mother cry by asking any more questions when they moved again the next week. That time they had only two rooms up-stairs over a barber shop, and Molly's mother died that summer. Then her father drank harder than ever, and never brought any money home, and by fall they had sold nearly everything that was left, and moved into one room in an old tenement-house, up two flights of stairs.

"Their grandmother had to go away every morning to look for work. She was too old to wash, or she might have had plenty to do. Sometimes she got odd jobs of cleaning, and sometimes she made buttonholes for a pants factory. It took nearly all the money she could make to pay the rent of that room, and often and often, Molly said, there were days when they had nothing but scraps of stale bread to eat. Sometimes there wasn't even that, and she and Dot would be so cold and hungry that they would huddle together in a corner and cry. She said it made her feel so awful to hear poor little Dot sobbing for something to eat, that she would have gone out on the streets and begged, but their grandmother always locked them up when she went away."

"What for?" interrupted Lloyd, who was listening with breathless attention.

"She was afraid that their father would come home drunk and find them alone. He didn't live with them any more, but several times, before she began locking them up, he staggered in, and frightened them dreadfully. Their ragged clothes and their half-starved looks seemed to make him furious. It hurt his conscience, I suppose, and that made him want to hurt somebody. Molly says he beat them sometimes till the neighbours interfered. More than once he shut them up in a dark closet, trying to make them tell where their grandmother kept her money. They couldn't tell him, for she didn't have any money, but he kept them shut up in the dark, hours at a time.

"One night he came in crosser than they had ever seen him, and threw things around dreadfully. He struck his old mother in the face, beat Molly, and threw a stick of wood at little Dot. It just missed putting out her right eye, and made such a deep cut over it that they had to send for a doctor to sew it up. He said she would carry the scar all her life, and he could not see how the blow had missed killing her.

"It nearly broke the old grandmother's heart. She sat up all night, and Molly says she remembers that time like a dreadful dream. Half the time the old woman was rocking Dot in her arms, crying over her, and half the time she was walking the floor.

"Molly says that now, when she shuts her eyes at night, she can hear her saying, over and over, 'Oh, my Jimmy! My Jimmy! To think that my only child should come to this! Oh, my Jimmy! The baby boy that was my sunshine, how can it be that you've become the sorrow of my life!' Then she'd walk up and down the room as if she were crazy, calling out, 'But it's the drink that did it! It's the drink, and a curse be on everything that helps to bring it into the world.'

"Molly says that she looked so terrible, with her white hair streaming over her shoulders, and her eyes staring, that she hid her face in the bedclothes. But she couldn't shut out the words. She shouted them so loud that the family in the next room couldn't sleep, and knocked on the wall for her to stop. But she only went on walking and wringing her hands and calling, 'A curse on all who buy and all who brew! A curse on every distiller! On every saloon-keeper! On every man who has so much as a finger in this business of death! May all the shame and the sin and the sorrow they have sown in other homes be reaped a hundredfold in their own!'

"I suppose it made such a strong impression on Molly, hearing her grandmother take on so terribly, that she remembered every word, and will as long as she lives. She said the rain poured that night till it leaked down on the bed, and she and Dot had to snuggle up together at the foot, to keep dry. Her grandmother walked the floor till daylight. The neighbours complained of her, and said that her troubles had unsettled her mind, and that she would have to be sent some place to be taken care of. All she could talk about was the drink that had ruined her Jimmy, and the awful things she prayed would happen to anybody who had anything to do with making or selling whiskey.

"She couldn't work any longer, and they were almost starving. One day she was taken to the almshouse, and the family in the next room took care of Molly and Dot until arrangements could be made to send them to an orphan asylum. It was hard to get them into one, you know, because their father was living.

"They stayed several weeks with those people, and Molly helped take care of the baby, for she was a big girl, eleven years old, then. Dot was seven, but so little and starved that she looked scarcely half that old. She couldn't do much to help, but they sent her on errands sometimes.

"One day she went to the meat-shop around the corner, and she never came back. Molly hunted in all the alleys and courtyards for her, until some one brought her a message from her father, that he had taken Dot away to another town. He didn't care what became of Molly, he said. She had been saucy to him, but no orphan asylum should have his baby. He'd hide her where she wouldn't be found in a hurry.

"Molly says she would have liked it at the asylum if Dot could have been with her, but because she couldn't it made her hate everything and everybody in the world. There was a big distillery in sight of her window. She could see the roof the first thing in the morning, when she opened her eyes, and the last thing at night. Many a time before she got out of bed she'd think of her grandmother's words and repeat them just like it was her prayers. She'd think 'It's drink that put me here, and it's what separated me from Dot,' and then she'd say, 'A curse on those who sell, and those who make it, and on every hand that helps to bring it into the world! Amen.'"

"How dreadful!" exclaimed the Little Colonel, with a shudder. "She is as bad as a heathen."

"But you can't wonder at it," said Betty. "We would have felt the same way in her place. Suppose it was your Papa Jack that had been made a drunkard, and that he'd begin to be mean to you, and make so much trouble that godmother would die, and you'd have to leave the House Beautiful and be sent to an asylum, and all on account of the saloons. Wouldn't you hate them and everything that helped keep them going?"

Lloyd only shivered at the thought, without answering. It was not possible for her to suppose such a horrible thing about her beloved father, but she felt the justice of Betty's view.

"While she was at the asylum," continued Betty, "some one sent a pile of old magazines, and among them she found the picture that we saw. She says that it looks exactly like Dot, and that is the way she used to stand and cry sometimes when she was cold and hungry, and there wasn't anything in the house to eat. It makes her perfectly miserable whenever she looks at it, but it is so much like Dot that she can't bear to give it up. Now you see why she didn't like us. It didn't seem fair to her that we should have so much to make us happy, when she has so little. She has had a hard enough time to spoil anybody's disposition, I think."

Lloyd was in tears by this time, and reaching across the table for the letter she had written about the Barley-bright witch, she began tearing it into pieces.

"Oh, if I'd only known," she said, "I never would have written those things about her. I'll write another one this afternoon, and tell Joyce all about her. Is she still crying in there, Betty?"

"No, she stopped before I left. I told her we would all try to find her little sister, and that I was sure godmother could do it, even if everybody else failed. But she didn't seem to think that there was much hope."

"Did you tell her about Fairchance?" asked Lloyd, "or Joyce's finding Jules's great-aunt Desiré, that time she went to the Little Sisters of the Poor?"

"No," said Betty.

"Then let me tell her," cried the Little Colonel, starting up eagerly.

She ran on into Molly's room, while thoughtful Betty slipped down-stairs to offer her services in Molly's place, that she might listen undisturbed to Lloyd's tale of comfort, – all about Jonesy and his brother, and the bear, who had found a fair chance to begin life again, in the home that the two little knights built for them, in their efforts to "right the wrong and follow the king." All about old great-aunt Desiré, who had been found in a pauper's home and brought back to her own again, through the Gate of the Giant Scissors, on Christmas Day in the morning.

"It is too good to be true," sighed Molly, when Lloyd had finished. "It might happen to some people, but it's too good to happen to me. It sounds like something out of a story-book."

"Most of the things in story-books had to happen first before they were written about," answered the Little Colonel. "You've got so many friends now that surely some of them will be able to do something to find her."

Presently Molly looked up, saying, in a hesitating way, "Several people have been good to me before, but I never thought about them doing it because they were my friends. I thought they treated me kindly just because they pitied me, and that made me cross."

Lloyd was turning the little ring that Eugenia had given her around on her finger, and something in the touch of the little lover's knot of gold recalled all that she had resolved about the "Road of the Loving Heart." It was the ring that made her say, gently, "You mustn't think that about Betty and me. We'll be your really truly friends just as we are Joyce's and Eugenia's."

Then to Molly's great surprise the Little Colonel's pretty face leaned over hers an instant, and she felt a quick kiss on her forehead. She lay there a moment longer without speaking, and then sat up, a bright smile flashing across her tear-swollen face. "Somehow the whole world seems different," she cried. "It seems so queer to think I've really got friends like other people."

There was a warm glow in the Little Colonel's heart when she went back to Betty's room. The consciousness that she had carried comfort and sunshine into another's life brightened the rainy day until it no longer seemed dark and dreary. That comfortable consciousness was still with her in the afternoon, when she sat down to write another letter to Joyce, – a letter, not filled this time with her own mishaps and misfortunes, but so full of sympathy for Molly's troubles that no one who read it could fail to be touched and interested.

CHAPTER VII

A FEAST OF SAILS

Now ring your merriest tune, ye silver bells of the magic caldron. 'Tis a birthday feast that awakes your chiming, so make your key-note joy. And now if the little princes and princesses will thrust their curious fingers into the steam as the water bubbles again, it will take them far away from the Cuckoo's Nest. They will see the village of Plainsville, Kansas, and the little brown house where the Ware family lived.

The day that the Little Colonel's letter reached Joyce was Holland's tenth birthday. One would not have dreamed that there was a party of ten boys in the parlour that bright September afternoon, for the shutters were closed, and every blind tightly drawn. Jack had darkened the room to give them a magic lantern exhibition, while Joyce was spreading the table under an apple-tree in the side yard. Mary, her funny little braids with their big bows of blue ribbon continually bobbing over her shoulders, was helping to carry out the curious dishes from the house that had taken all morning to prepare.

There was never much money to spend in entertainments in the little brown house, but birthdays never passed unheeded. Love can always find some way to keep the red-letter days of its calendar. Joyce and her mother had planned a novel supper for Holland and his friends, thinking it would make a merry feast for them to laugh over now, and a pleasant memory by and by, when three score years had been added to his ten. Looking back on the day when somebody cared that it was his birthday, and celebrated it with loving forethought, would kindle a glow in his heart, no matter how old and white-haired he might live to be.

The little mother could not take much time from her sewing, but she suggested and helped with the verses, and came out when the table was nearly ready, to add a few finishing touches.

A Feast of Sails, Joyce called it, saying that, if Cinderella's godmother could change a pumpkin into a gilded coach, there was no reason why they should not transform an ordinary luncheon into a fleet of boats, for a boy whose greatest ambition was to be a naval officer, and who was always talking about the sea.

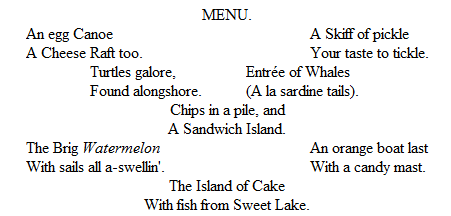

These were the invitations, printed in Jack's best style, and decorated by Joyce with a little water-colour sketch of a ship in full sail:

Please come, hale and hearty,To Holland Ware's party,September, the twenty-first day,And partake in a bunchOf a queer birthday lunch,And afterward join in a play.The things which we'll eatWill be boats, sour and sweet,With maybe an entrée of whales.Will you please to arriveAwhile before five,The hour that this boat-luncheon sails.The invitations aroused great interest among all Holland's friends, and every boy was at the gate long before the appointed hour, curious to see the "boats sour and sweet" that could be eaten. But even Holland did not know what was in store for them. Joyce had driven him out of the kitchen while she was preparing the surprise, and would not begin to set the table until Jack had marshalled every boy into the dark parlour and begun his magic lantern show. The baby was with them, a baby no longer, he stoutly declared, as he had that day been promoted from kilts to his first pair of trousers, and he insisted on being called henceforth by his own name, Norman.

As he and Jack were to be added to the party of ten, the table was set for twelve. It was a gay sight when everything was ready. From the mirror lake in the middle, on which a dozen toy swans were afloat, arose a lighthouse made of doughnuts. It was surmounted by a little lantern from which floated a tiny flag. At one end of the table a huge watermelon cut lengthwise, and furnished with masts and sails of red crêpe paper, looked like a brig just launched. At the other end rose the great white island of the birthday cake, with its ten red candles. All down the sides of the table was a flutter of yellow and green and white and blue sails, for at each plate was a little fleet sporting the colours of the rainbow.

It had been an interesting task to make the dressed eggs into canoes, to cut the cheese into square rafts, and hollow out the long cucumber pickles into skiffs, fitting sails or pennons to each broomstraw mast. It had been still more interesting to change a bag of big fat raisins into turtles, by poking five cloves and a bit of stem into each one for the head, legs, and tail.

Joyce took an artistic pleasure in arranging the orange boats around the table. She had made them by cutting an orange in two, and putting a stick of peppermint candy in each half for a mast, and they had a foreign, Chinese look with their queer sails, flaming with little red-ink dragons. Jack had drawn them. Here and there, over the sea of white tablecloth, she had scattered candy fish and the raisin turtles. At the last moment there were potato chips to be heated, and islands of sandwiches and jelly to distribute, and the can of sardines to open. Mary had insisted on having the sardines to personate whales, and she herself served one to each guest on a little shell-shaped plate belonging to her set of doll dishes. It had taken so long to prepare all these boats, that Joyce had had no time to decorate the menu cards as she had planned, but Jack had cut them in the shape of an anchor, and stuck a fish-hook through each one for a souvenir. This was what was printed on them:

Mary gave the signal when everything was ready, a long toot on an old tin whistle that sounded like a fog-horn. She blew it through the keyhole of the parlour door, expecting a speedy answer, but was not prepared for the sensation her summons created. The door flew open so suddenly that she was nearly taken off her feet, and the boys fell all over each other in their race for the table. When they were all seated, Norman, standing up at the foot of the table, repeated the rhyme which Joyce had carefully taught him: