Полная версия

Полная версияThe Common Objects of the Country

Now here was this impertinent little animal taking a walk close to the wicket, in spite of the bats, ball, and runners. In order to watch its proceedings, I released it, and followed it in its progress. After watching for a few minutes, I happened to look up for a moment; and when I again looked for the creature, it was gone, and I could not find it again.

Subsequently I became sufficiently expert to find them whenever I wished; and if I wanted a field-mouse, seldom had to examine more than a square yard of ground without finding one.

They are very injurious little creatures, for they are not content with eating corn, but nibble the young shoots of various plants, and sometimes strip young trees of their bark.

Fortunately we have allies in air and on earth, in the persons of owls and kestrels, stoats and weasels, or the damage done by these red-skinned marauders would be more than serious.

Some idea of the damage that may be done by the aggregate numbers of these small quadrupeds may be formed from the fact that in Dean Forest and the New Forest great numbers of holly plants were entirely destroyed by them, they having eaten off the bark for a distance of several inches from the ground. And other trees were favoured with the notice of the field-mouse, but in a different mode. Great numbers of oak and chestnuts were found dead, and pulled up; and when pulled up, it was seen that their roots had been gnawed through, about two inches below the level of the ground.

Various modes of destroying the marauders were put in practice, such as traps, poison, &c., but the most effectual was, as effectual things generally are, the most simple.

A great number of holes were dug in the ground, about two feet long, eighteen inches wide, and eighteen inches deep. This is the measurement at the bottom of the hole; but at the top the hole was only eighteen inches long and nine wide, so that when mice fell into it, they were unable to escape.

In these holes upwards of forty thousand mice were taken in less than three months, irrespective of those that were removed from the holes by the stoats, weasels, crows, magpies, owls, and other creatures.

Like most of the mouse family, the field-mouse is easily tamed; and I have seen one that would come to the side of its cage, and take a grain of com from its owner’s fingers.

HARVEST-MOUSE.

There is another kind of mouse which may be found in the autumn, together with its most curious nest. This is the Harvest-mouse, the tiniest of British quadrupeds, two harvest-mice being hardly equal in weight to a halfpenny.

The chief point of interest in this little creature is its nest, which is not unfrequently found by mowers and haymakers when they choose to exert their eyes.

One of these nests, that was brought to me by a mower, was about the size of a cricket ball, and almost as spherical. It was composed of dried grass-stems, interwoven with each other in a manner equally ingenious and perplexing. It was hollow, without even a vestige of an entrance; and the substance was so thin that every object would be visible through the walls. How it was made to retain its spherical form, and how the mice were to find ingress and egress, I could not even imagine. The nest was fastened to two strong and coarse stems of grass that had grown near a ditch, and had overgrown themselves in consequence of a superabundance of nourishment.

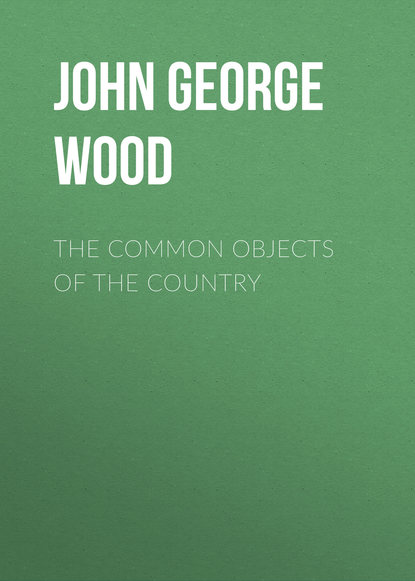

WATER-RAT.

If we walk along the bank of a stream or a pond, we shall probably hear a splash, and looking in its direction, may see a creature diving or swimming, which creature we call a Water-rat; to the title of Rat, however, it has but little right, and ought properly to be called the “Water-vole”.

On examining the banks we shall find the entrance to its domicile, being a hole in the earth, just above the water, and generally, where possible, made just under a root or a large stone. Sometimes the hole is made at some height above the water, and then it often happens that the kingfisher takes possession, and there makes its home. Whether it ejects the rat or not I cannot say, but I should think that it is quite capable of doing so. Many a time I have seen the entrance to a rat-hole decorated with a few stray fish-bones, which the rustics told me were the relics of fish brought there and eaten by the water-rat. But I soon found out that fish-bones were a sign of kingfishers, and not of rats; and so guided, found plenty of the beautiful eggs of this beautiful bird. Excepting the eggs of swallows and martins, I hardly know any so delicately beautiful as those of the kingfisher, with their slight rose tint and semi-transparent shell. But, alas! when the interior of the egg is removed, the pearly pinkiness vanishes, and the shell becomes of a pure white, very pretty, but not containing a tithe of its former beauty.

The piscatorial propensities of the kingfisher are not the only cause of the slanderous reports concerning the water-vole, and its crime of killing and eating fish. The common house-rat often frequents the water-side; and, it being a great flesh-eater, certainly does catch and eat the fish.

But the water-rat is a vegetable feeder, and I believe almost, if not entirely, a vegetarian in diet. That it is so in individual cases, at all events, I can personally testify, having seen the creature engaged in eating.

In former days, when I thought the water-rats ate fish, I waged war against them, for which warfare there are great facilities at Oxford. However, a circumstance occurred which showed me that I had been wrong.

I saw a water-rat sitting on a kind of raft that had formed from a bundle of reeds which had been cut and were floating down the river. Seeing it busily at work feeding, I took it for granted that it was eating a captured fish, and shot it accordingly, stretching it dead on its reed raft.

On rowing up to the spot, I was rather surprised to find that there was no fish there; and on examining the reeds, I rather wondered at the regular grooves cut by my shot. But a closer inspection revealed a very different state of things; namely, that the poor dead rat was quite innocent of fish eating, and had been gnawing the green bark from the reeds, the grooves being the marks left by its teeth. After this I gave up rat shooting on principle.

Once, though, a rather curious circumstance occurred.

In my possession was a pet pistol, which would throw a ball with great accuracy, and I considered myself sure of an apple at sixteen paces. One day, just as I was standing by a branch of the river Cherwell, I saw a water-rat sitting on the root of a tree at the opposite side of the river, and watching me closely. The river was not above twelve or fourteen yards wide; and the rat presented so good a mark that I fired at him, and, of course, expected to see him on his back.

But there sat the rat, quite still on the stump, and about two inches below him the round hole where the bullet had struck.

As the creature seemed determined to stay there, I reloaded, and took a good aim, determined to make sure of him. As the smoke cleared away, I had the satisfaction of seeing the rat in exactly the same position, and another bullet-hole close by the former. Four shots I made at that provoking animal, and four bullets did I deposit just under him. As I was reloading for a fifth shot, the rat walked calmly down the stump, slid into the water, and departed.

Now, whether he acted from sheer impertinence, or whether he was stunned by the violent blow beneath him, I cannot say. The latter may perhaps be the case, for squirrels are killed in North America by the shock of the bullet against the bough on which they sit, so that no hole is made in their skins, and the fur receives no damage. Perhaps the rat was actuated by a supreme contempt for me and my shooting powers; and, as the result showed, was quite justified in his opinion.

CHAPTER II

SHREW-MOUSE—DERIVATION OF ITS NAME—SHREW-ASH—THE SPIRIT AND THE LIFE—WATER-SHREW—ITS HABITS—THE MOLE—MOLE-HILL—A PET MOLE—THE WEASEL.

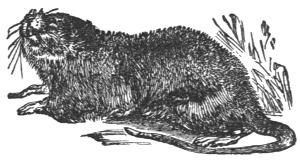

I have already mentioned that the water-rat has little claim to the title of rat; and there is another creature which has even less claim to the title of mouse. This is the Shrew, or Shrew-mouse as it is generally called. This creature bears a very close relationship to the hedgehog, and is a distant connection of the mole; but with the mouse it has nothing to do.

SHREW-MOUSE.

Numbers of the shrews may be found towards the end of the autumn lying dead on the ground, from some cause at present not perfectly ascertained. If one of these dead shrews be taken, and its little mouth opened, an array of sharply-pointed teeth will be seen, something like those of the mole, very like those of the hedgehog; but not at all resembling those of the mouse.

The shrew is an insect and worm-devouring creature, for which purpose its jaws, teeth, and whole structure are framed. A rather powerful scent is diffused from the shrew; and probably on that account cats will not eat a shrew, though they will kill it eagerly.

On examining Webster’s Dictionary for the meaning of the word “shrew,” we find three things.

Firstly, that it signifies “a peevish, brawling, turbulent, vexatious woman”.

Secondly, that it signifies “a shrew-mouse”.

Thirdly, that it is derived from a Saxon word, “screawa,” a combination of letters which defies any attempt at pronunciation, except perhaps by a Russian or a Welshman.

Now, it may be a matter of wonder that the same word should be used to represent the very unpleasant female above-mentioned, and also such a pretty, harmless little creature as the shrew. The reason is shortly as follows.

In days not long gone by, the shrew was considered a most poisonous creature, as may be seen in the works of many authors. In the time of Katherine—the shrew most celebrated of all shrews—any cow or horse that was attacked with cramp, or indeed with any sudden disease, was supposed to have suffered in consequence of a shrew running over the injured part. In those days homœopathic remedies were generally resorted to; and nothing but a shrew-infected plant could cure a shrew-infected animal. And the shrew-ash, as the remedial plant was called, was prepared in the following manner.

In the stem of an ash-tree a hole was bored; into the hole a poor shrew was thrust alive, and the orifice immediately closed with a wooden plug. The animal strength of the shrew passed by absorption into the substance of the tree, which ever after cured shrew-struck animals by the touch of a leafy branch.

The poor creature that was imprisoned, Ariel-like, in the tree, was, fortunately for itself, not gifted with Ariel’s powers of life; and the orifice of the hole being closed by the plug, we may hope that its sufferings were not long, and that it perished immediately for want of air. Still, our fathers were terribly and deliberately cruel; and if the shrew’s death was a merciful one, no credit is due to the authors of it.

For on looking through a curious work on natural history, of the date of 1658, where each animal is treated of medicinally, I find recipes of such terrible cruelty that I refrain from giving them, simply out of tenderness for the feelings of my reader. Torture seems to be a necessary medium of healing; and if a man suffers from “the black and melancholy cholic,” or “any pain and grief in the winde-pipe or throat,” he can only be eased therefrom by medicines prepared from some wretched animal in modes too horrid to narrate, or even to think of.

We are not quite so bad at the present day; but still no one with moderate feelings of compassion can pass through our streets without being greatly shocked at the wanton cruelties practised by human beings on those creatures that were intended for their use, but not as mere machines. Charitably, we may hope that such persons act from thoughtlessness, and not from deliberate cruelty; for it does really seem a new idea to many people that the inferior animals have any feelings at all.

When a horse does not go fast enough to please the driver, he flogs it on the same principle that he would turn on steam to a locomotive engine, thinking about as much of the feelings of one as of the other.

Much of the present heedlessness respecting animals is caused by the popular idea that they have no souls, and that when they die they entirely perish. Whence came that most preposterous idea? Surely not from the only source where we might expect to learn about souls—not from the Bible; for there we distinctly read of “the spirit of the sons of man”; and immediately afterwards of “the spirit of the beast,” one aspiring, and the other not so. And the necessary consequence of the spirit is a life after the death of the body. Let any one wait in a frequented thoroughfare for only one short hour, and watch the sufferings of the poor brutes that pass by. Then, unless he denies the Divine Providence, he will see clearly that unless these poor creatures were compensated in another life, there is no such quality as justice.

It is owing to sayings such as these, that men come to deny an all-ruling Providence, and so become infidels. They don’t examine the Scriptures for themselves, but take for granted the assertions of those who assume to have done so, and seeing the falsity of the assertion, naturally deduce therefrom the falsity of its source. If a man brings me a cup of putrid water, I naturally conclude that the source is putrid too. And when a man hears horrible and cruel doctrines, which are asserted by theologians to be the religion of the Scriptures, it is no wonder that he turns with disgust from such a religion, and tries to find rest in infidelity. In such a case, where is the fault?

All created things in which there is life, must live for ever. There is only one life, and all living things only live as being recipients; so that as that life is immortality, all its recipients are immortal.

If people only knew how much better an animal will work when kindly treated, they would act kindly towards it, even from so low a motive. And it is so easy to lead these animals by kindness, which will often induce an obstinate creature to obey where the whip would only confirm it in its obstinacy. All cruelty is simply diabolical, and can in no way be justified.

Supposing that the two cases could be reversed for just one hour, what a wonderful change there would be in the opinion of men; for it may be assumed that the person most given to inflicting pain and suffering is the least tolerant of it himself.

There is, perhaps, hardly one of my readers who does not know some one person who finds an exquisite delight in hurting the feelings of others by various means, such as ridicule, practical jokes, ill-natured sayings, and so on. If so, he will be tolerably certain to find that the same person is especially thin-skinned himself, and resents the least approach to a joke of which he is the subject.

So, if the shrew were to be the afflicted individual, and the human the victim, there would be found no one so averse to the medicinal process as he who had formerly resorted to it under different circumstances.

This principle is finely carried out, in the terrible scene of Dennis, the executioner’s, last hours in Barnaby Rudge.

These are not pleasant subjects; and we will pass on to another shrew that is generally found in the water, and called from thence the Water-shrew. It is a creature that may be found in many running streams, if the eyes are sharp enough to observe it, and is well worth examination. As it dives and runs along the bottom of the stream, it appears to be studded with tiny silver beads, or glittering pearls, on account of the air-bubbles that adhere to its fur. I have seen a whole colony of them disporting themselves in a little brooklet not two feet wide, and so had a good opportunity of inspecting them.

WATER-SHREW.

I may mention here, as has been done in one or two other works, that nothing is easier than to watch animals or birds in their state of liberty. All that is required is perfect quiet. If an observer just sits down at the foot of a tree, and does not move, the most timid creatures will come within a few yards as freely as if no human being were within a mile. If he can shroud himself in branches or grass or fern, so much the better; but quiet is the chief essential.

It is impossible to form an idea of the real beauty of animal life, without seeing it displayed in a free and unconstrained state; and more real knowledge of natural history will be gained in a single summer spent in personal examination, than by years of book study.

The characters of creatures come out so strongly; they have such quaint, comical, little ways with them; such assumptions of dignity and sudden lowering of the same; such clever little cheateries; such funny flirtations and coquetries, that I have many a time forgotten myself, and burst into a laugh that scattered my little friends for the next half-hour. It is far better than a play, and one gets the fresh air besides.

These little water-shrews are most active in their sports and their work, for which latter purpose they make regular paths along the banks. And as to their sport, they chase one another in and out of the water, making as great a splash as possible, whisk round roots, dodge behind stones, and act altogether just like a set of boys let loose from the school-room. And then—what a revulsion of feeling to see a stuffed water-shrew in a glass-case!

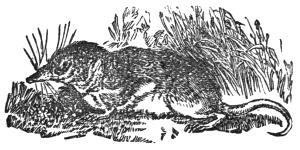

Now for a few words respecting the distant relation of the shrews, namely, the mole. Of its near relation, the hedgehog, there will not be time to speak.

Every one is familiar with the little heaps of earth thrown up by the mole, and called mole-hills. But as the animal itself lives almost entirely underground, comparatively little is known of it; at all events, to the generality of those who see the hills. The mole is not often seen alive; and few who see it suspended among the branches by the professional killer would form any conception of the real character of this subterranean animal.

Meek and quiet as the mole looks, it is one of the fiercest, if not the very fiercest of animals; it labours, eats, fights, and loves as if animated by one of the furies, or rather by all of them together.

MOLE.

Intervals of profound rest alternate with savage action; and according to the accounts of country folks near Oxford, it works and rests at regular intervals of three hours each.

Useful as these creatures are as subsoil drain-makers, they sometimes increase to an inconvenient extent, and then the professed mole-catcher comes into practice, and destroys the moles with an apparatus apparently inadequate to such a purpose. But the mole is easily killed, and pressure he cannot survive; so the traps are formed for the purpose of squeezing the mole, not of smashing or strangling him.

The mole-catchers are in the habit of suspending their victims on branches, mostly of the willow or similar trees; but their object I could never make out, nor could they give me any reason, except that it was the custom.

When a mole is taken out of the ground, very little earth clings to it. There is always some on its great digging claws; but very little indeed on its fur, which is beautifully formed to prevent such accumulation. The fur of most animals “sets” in some definite direction, according to its position on the body; but that of the mole has no particular set, and is fixed almost perpendicularly on the creature’s skin, much like the pile of velvet. Indeed the mole’s fur has much the feel of silk-velvet; and so the title of the “Little gentleman in the velvet coat” is justly applied.

Those small heaps of earth that are so common in the fields, and called mole-hills, are merely the result of the mole’s travelling in search of the earth-worms, on which it principally feeds; and in their structure there is nothing remarkable.

But the great mole-hill, or mole-palace, in which the animal makes its residence, is a very different affair, and complicated in its structure. In it is found a central chamber in which the mole resides; and round this chamber there run galleries or corridors in a regular series, so as to form a kind of labyrinth, by means of which the creature may make its escape, if threatened with danger.

The accompanying cut shows a section of the mole-palace.

MOLE-HILL.

This palace is formed, if possible, under the protection of large stones, roots of trees, thick bushes, or some such situation; and is located as far as possible from paths or roads.

The food of the mole mostly consists of earth-worms, in search of which it drives these tunnels with such assiduity. The depth of the tunnel is necessarily regulated by the position of the worms; so that in warm pleasant days or evenings the run, as it is called, is within a few inches of the surface; but in winter the worms retire deeply into the unfrozen soil, and thither the mole must follow them. For this purpose it sinks perpendicular shafts, and from thence drives horizontal tunnels. It may be seen how useful this provision is when one thinks of the work that is done by the mole when providing for its own sustenance.

In the cold months, it drives deeply into the ground, thereby draining it, and preventing the roots of plants from becoming sodden by the retention of water above; and the earth is brought from below, where it was useless, and, with all its properties inexhausted by crops, is laid on the surface, there to be frozen, the particles to be forced asunder by the icy particles with which it is filled, and, after the thaw, to be vivified by the oxygen of the atmosphere, and made ready for the reception of seeds.

The worms have a mission of a similar nature; but their tunnels are smaller, and so are their hills. Every floriculturist knows how useful for certain plants are the little heaps of earth left by the worms at the entrance of their holes. And by the united exertions of moles and worms a new surface is made to the earth, even without the intervention of human labour.

Among other pets, I have had a mole—rather a strange pet, one may say; but I rather incline to pets, and have numbered among them creatures that are not generally petted—snakes, to wit—but which are very interesting creatures, notwithstanding.

Being very desirous of watching the mole in its living state, I directed a professional catcher to procure one alive, if possible; and after a while the animal was produced. At first there was some difficulty in finding a proper place in which to keep a creature so fond of digging; but the difficulty was surmounted by procuring a tub, and filling it half full of earth.

In this tub the mole was placed, and instantly sank below the surface of the earth. It was fed by placing large quantities of earth-worms or grubs in the cask; and the number of worms that this single mole devoured was quite surprising.

As far as regards actual inspection, this arrangement was useless; for the mole never would show itself, and when it was wanted for observation, it had to be dug up. But many opportunities for investigating its manners were afforded by taking it from its tub, and letting it run on a hard surface, such as a gravel-walk.

There it used to run with some speed, continually grubbing with its long and powerful snout, trying to discover a spot sufficiently soft for a tunnel. More than once it did succeed in partially burying itself, and had to be dragged out again, at the risk of personal damage. At last it contrived to slip over the side of the gravel-walk, and, finding a patch of soft mould, sank with a rapidity that seemed the effect of magic. Spades were put in requisition; but a mole is more than a match for a spade, and the pet mole was never seen more.