Полная версия

Полная версияStory of the Bible Animals

"The Arabs, gathering with their goats and sheep around the wells to-day, recall the recollection of that distant time when 'Jacob went on his journey, and came into the land of the people of the east. And he looked, and behold a well in the field, and lo! there were three flocks of sheep lying by it,' &c. The picture of that scene would be an illustration of Arab daily life in the Nubian deserts, where the present is a mirror of the past."

Owing to the great number of Sheep which they have to tend, and the peculiar state of the country, the life of the shepherd in Palestine is even now very different from that of an English shepherd, and in the days of the early Scriptures the distinction was even more distinctly marked.

Sheep had to be tended much more carefully than we generally think. In the first place, a thoughtful shepherd had always one idea before his mind,—namely, the possibility of obtaining sufficient water for his flocks. Even pasturage is less important than water, and, however tempting a district might be, no shepherd would venture to take his charge there if he were not sure of obtaining water. In a climate such as ours, this ever-pressing anxiety respecting water can scarcely be appreciated, for in hot climates not only is water scarce, but it is needed far more than in a temperate and moist climate. Thirst does its work with terrible quickness, and there are instances recorded where men have sat down and died of thirst in sight of the river which they had not strength to reach.

In places therefore through which no stream runs, the wells are the great centres of pasturage, around which are to be seen vast flocks extending far in every direction. These wells are kept carefully closed by their owners, and are only opened for the use of those who are entitled to water their flocks at them.

Noontide is the general time for watering the Sheep, and towards that hour all the flocks may be seen converging towards their respective wells, the shepherd at the head of each flock, and the Sheep following him. See how forcible becomes the imagery of David, the shepherd poet, "The Lord is my Shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures (or, in pastures of tender grass): He leadeth me beside the still waters" (Ps. xxiii. 1, 2). Here we have two of the principal duties of the good shepherd brought prominently before us,—namely, the guiding of the Sheep to green pastures and leading them to fresh water. Very many references are made in the Scriptures to the pasturage of sheep, both in a technical and a metaphorical sense; but as our space is limited, and these passages are very numerous, only one or two of each will be taken.

In the story of Joseph, we find that when his father and brothers were suffering from the famine, they seem to have cared as much for their Sheep and cattle as for themselves, inasmuch as among a pastoral people the flocks and herds constitute the only wealth. So, when Joseph at last discovered himself, and his family were admitted to the favour of Pharaoh, the first request which they made was for their flocks. "Pharaoh said unto his brethren, What is your occupation? And they said unto Pharaoh, Thy servants are shepherds, both we, and also our fathers.

"They said moreover unto Pharaoh, For to sojourn in the land are we come; for thy servants have no pasture for their flocks; for the famine is sore in the land of Canaan: now therefore, we pray thee, let thy servants dwell in the land of Goshen."

This one incident, so slightly remarked in the sacred history, gives a wonderfully clear notion of the sort of life led by Jacob and his sons. Forming, according to custom, a small tribe of their own, of which the father was the chief, they led a pastoral life, taking their continually increasing herds and flocks from place to place as they could find food for them. For example, at the memorable time when the story of Joseph begins, he was sent by his father to his brothers, who were feeding the flocks, and he wandered about for some time, not knowing where to find them. It may seem strange that he should be unable to discover such very conspicuous objects as large flocks of sheep and goats, but the fact is that they had been driven from one pasture-land to another, and had travelled in search of food all the way from Shechem to Dothan.

In 1 Chron. iv. 39, 40, we read of the still pastoral Israelites that "they went to the entrance of Gedor, even unto the east side of the valley, to seek pasture for their flocks. And they found fat pasture and good, and the land was wide, and quiet, and peaceable."

How it came to be quiet and peaceable is told in the context. It was peaceable simply because the Israelites were attracted by the good pasturage, attacked the original inhabitants, and exterminated them so effectually that none were left to offer resistance to the usurpers. And we find from this passage that the value of good pasture-land where the Sheep could feed continually without being forced to wander from one spot to another was so considerable, that the owners of the flocks engaged in war, and exposed their own lives, in order to obtain so valuable a possession.

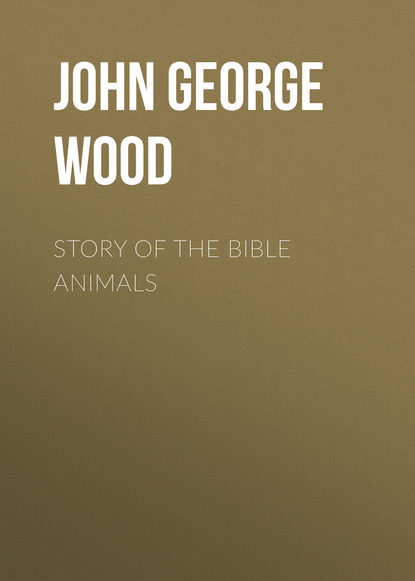

JACOB MEETS RACHEL AT THE WELL.

We will now look at one or two of the passages that mention watering the Sheep—a duty so imperative on an Oriental shepherd, and so needless to our own.

In the first place we find that most graphic narrative which occurs in Gen. xxix. to which a passing reference has already been made. When Jacob was on his way from his parents to the home of Laban in Padan-aram, he came upon the very well which belonged to his uncle, and there saw three flocks of Sheep lying around the well, waiting until the proper hour arrived. According to custom, a large stone was laid over the well, so as to perform the double office of keeping out the sand and dust, and of guarding the precious water against those who had no right to it. And when he saw his cousin Rachel arrive with the flock of which she had the management, he, according to the courtesy of the country and the time, rolled away the ponderous barrier, and poured out water into the troughs for the Sheep which Rachel tended.

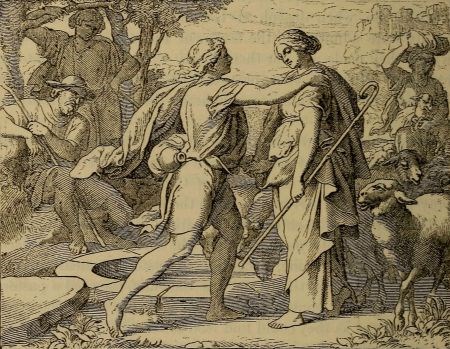

EASTERN SHEPHERD WATCHING HIS FLOCK.

About two hundred years afterwards, we find Moses performing a similar act. When he was obliged to escape into Midian on account of his fatal quarrel with a tyrannical Egyptian, he sat down by a well, waiting for the time when the stone might be rolled away, and the water be distributed. Now it happened that this well belonged to Jethro, the chief priest of the country, whose wealth consisted principally of Sheep. He entrusted his flock to the care of his seven daughters, who led their Sheep to the well and drew water as usual into the troughs. Presuming on their weakness, other shepherds came and tried to drive them away, but were opposed by Moses, who drove them away, and with his own hands watered the flock.

Now in both these examples we find that the men who performed the courteous office of drawing the water and pouring it into the sheep-troughs married afterwards the girl to whose charge the flocks had been committed. This brings us to the Oriental custom which has been preserved to the present day.

The wells at which the cattle are watered at noon-day are the meeting-places of the tribe, and it is chiefly at the well that the young men and women meet each other. As each successive flock arrives at the well, the number of the people increases, and while the sheep and goats lie patiently round the water, waiting for the time when the last flock shall arrive, and the stone be rolled off the mouth of the well, the gossip of the tribe is discussed, and the young people have ample opportunity for the pleasing business of courtship.

As to the passages in which the wells, rivers, brooks, water-springs, are spoken of in a metaphorical sense, they are too numerous to be quoted.

And here I may observe, that in reality the whole of Scripture has its symbolical as well as its outward signification; and that, until we have learned to read the Bible strictly according to the spirit, we cannot understand one-thousandth part of the mysteries which it conceals behind its veil of language; nor can we appreciate one-thousandth part of the treasures of wisdom which lie hidden in its pages.

Another duty of the shepherd of ancient Palestine was to guard his flock from depredators, whether man or beast. Therefore the shepherd was forced to carry arms; to act as a sentry during the night; and, in fact, to be a sort of irregular soldier. A fully-armed shepherd had with him his bow, his spear, and his sword, and not even a shepherd lad was without his sling and the great quarter-staff which is even now universally carried by the tribes along the Nile—a staff as thick as a man's wrist, and six or seven feet in length. He was skilled in the use of all these weapons, especially in that of the sling.

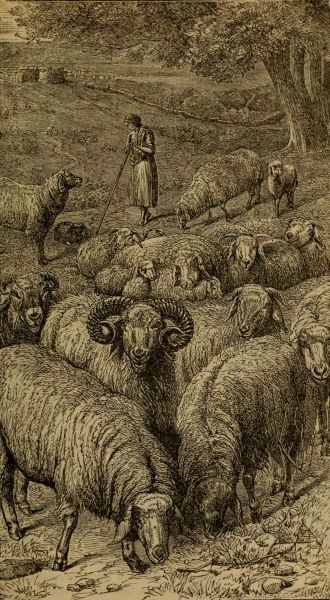

DAVID GATHERS STONES FROM THE BROOK TO CAST AT GOLIATH.

In these days, the sling is only considered as a mere toy, whereas, before the introduction of fire-arms, it was one of the most formidable weapons that could be wielded by light troops. Round and smooth stones weighing three or four ounces were the usual projectiles, and, by dint of constant practice from childhood, the slingers could aim with a marvellous precision. Of this fact we have a notable instance in David, who knew that the sling and the five stones in the hand of an active youth unencumbered by armour, and wearing merely the shepherd's simple tunic, were more than a match for all the ponderous weapons of the gigantic Philistine.

It has sometimes been the fashion to attribute the successful aim of David to a special miracle, whereas those who are acquainted with ancient weapons know well that no miracle was wrought, because none was needed; a good slinger at that time being as sure of his aim as a good rifleman of our days.

The sling was in constant requisition, being used both in directing the Sheep and in repelling enemies: a stone skilfully thrown in front of a straying Sheep being a well-understood signal that the animal had better retrace its steps if it did not want to feel the next stone on its back.

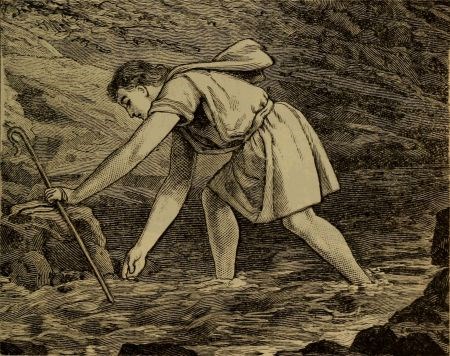

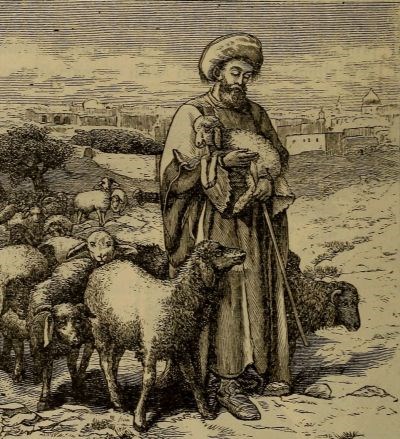

AN EASTERN SHEPHERD.

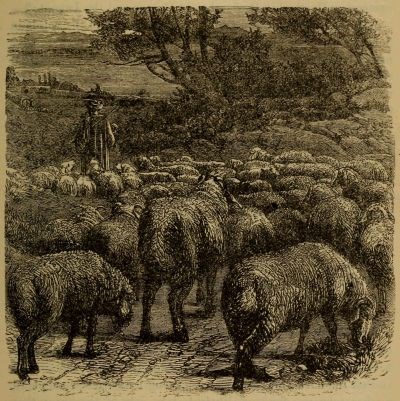

Passing his whole life with his flock, the shepherd was identified with his Sheep far more than is the case in this country. He knew all his Sheep by sight, he called them all by their names, and they all knew him and recognised his voice. He did not drive them, but he led them, walking in their front, and they following him. Sometimes he would play with them, pretending to run away while they pursued him, exactly as an infant-school teacher plays with the children.

Consequently, they looked upon him as their protector as well as their feeder, and were sure to follow wherever he led them.

SHEEP FOLLOWING THEIR SHEPHERD.

We must all remember how David, who had passed all his early years as a shepherd, speaks of God as the Shepherd of Israel, and the people as Sheep; never mentioning the Sheep as being driven, but always as being led. "Thou leddest Thy people like a flock, by the hands of Moses and Aaron" (Ps. lxxvii. 20); "The Lord is my Shepherd.... He leadeth me beside the still waters" (Ps. xxiii. 1, 2); "Lead me in a plain path, because of mine enemies" (Ps. xxvii. 11); together with many other passages too numerous to be quoted.

Our Lord Himself makes a familiar use of the same image: "He calleth his own sheep by name, and leadeth them out And when he putteth forth his own sheep, he goeth before them, and the sheep follow him: for they know his voice."

Although the shepherds of our own country know their Sheep by sight, and say that there is as much difference in the faces of Sheep as of men, they have not, as a rule, attained the art of teaching their Sheep to recognise their names. This custom, however, is still retained, as may be seen from a well-known passage in Hartley's "Researches in Greece and the Levant:"—

"Having had my attention directed last night to the words in John x. 3, I asked my man if it were usual in Greece to give names to the sheep. He informed me that it was, and that the sheep obeyed the shepherd when he called them by their names. This morning I had an opportunity of verifying the truth of this remark. Passing by a flock of sheep, I asked the shepherd the same question which I had put to the servant, and he gave me the same answer. I then bade him call one of his sheep. He did so, and it instantly left its pasturage and its companions, and ran up to the hands of the shepherd, with signs of pleasure, and with a prompt obedience which I had never before observed in any other animal.

"It is also true that in this country, 'a stranger will they not follow, but will flee from him.' The shepherd told me that many of his sheep were still wild, that they had not learned their names, but that by teaching them they would all learn them."

Generally, the shepherd was either the proprietor of the flock, or had at all events a share in it, of which latter arrangement we find a well-known example in the bargain which Jacob made with Laban, all the white Sheep belonging to his father-in-law, and all the dark and spotted Sheep being his wages as shepherd. Such a man was far more likely to take care of the Sheep than if he were merely a paid labourer; especially in a country where the life of a shepherd was a life of actual danger, and he might at any time be obliged to fight against armed robbers, or to oppose the wolf, the lion, or the bear. The combat of the shepherd David with the last-mentioned animals has already been noticed.

In allusion to the continual risks run by the Oriental shepherd, our Lord makes use of the following well-known words:—"The thief cometh not but for to steal, and to kill, and to destroy: I am come that they might have life, and have it more abundantly. I am the Good Shepherd: the good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep. But he that is an hireling, … whose own the sheep are not, seeth the wolf coming, and leaveth the sheep, and fleeth: and the wolf catcheth them, and scattereth the sheep. The hireling fleeth because he is an hireling, and careth not for the sheep."

Owing to the continual moving of the Sheep, the shepherd had very hard work during the lambing time, and was obliged to carry in his arms the young lambs which were too feeble to accompany their parents, and to keep close to him those Sheep who were expected soon to become mothers. At that time of year the shepherd might constantly be seen at the head of his flock, carrying one or two lambs in his arms, accompanied by their mothers.

In allusion to this fact Isaiah writes: "His reward is with Him, and His work before Him. He shall feed His flock like a shepherd; He shall gather the lambs with His arms and carry them in His bosom, and shall gently lead them that are with young" (or, "that give suck," according to the marginal reading). Here we have presented at once before us the good shepherd who is no hireling, but owns the Sheep; and who therefore has "his reward with him, and his work before him;" who bears the tender lambs in his arms, or lays them in the folds of his mantle, and so carries them in his bosom, and leads by his side their yet feeble mothers.

Frequent mention is made of the folds in which the Sheep are penned; and as these folds differed—and still differ—materially from those of our own land, we shall miss the force of several passages of Scripture if we do not understand their form, and the materials of which they were built. Our folds consist merely of hurdles, moveable at pleasure, and so low that a man can easily jump over them, and so fragile that he can easily pull them down. Moreover, the Sheep are frequently enclosed within the fold while they are at pasture.

If any one should entertain such an idea of the Oriental fold, he would not see the force of the well-known passage in which our Lord compares the Church to a sheepfold, and Himself to the door. "He that entereth not by the door into the sheepfold, but climbeth up some other way, the same is a thief and a robber. But he that entereth in by the door is the shepherd of the sheep. To him the porter openeth, and the sheep hear his voice.... All that ever came before me are thieves and robbers: but the sheep did not hear them. I am the door: by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved, and shall go in and out, and find pasture."

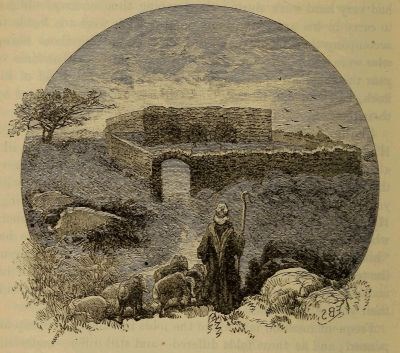

ANCIENT SHEEP PEN.

Had the fold here mentioned been a simple enclosure of hurdles, such an image could not have been used. It is evident that the fold to which allusion was made, and which was probably in sight at the time when Jesus was disputing with the Pharisees, was a structure of some pretensions; that it had walls which a thief could only enter by climbing over them—not by "breaking through" them, as in the case of a mud-walled private house; and that it had a gate, which was guarded by a watchman.

In fact, the fold was a solid and enduring building, made of stone. Thus in Numbers xxxii. it is related that the tribes of Reuben and Gad, who had great quantities of Sheep and other cattle, asked for the eastward side of Jordan as a pasture-ground, promising to go and fight for the people, but previously to build fortified cities for their families, and folds for their cattle, the folds being evidently, like the cities, buildings of an enduring nature.

In some places the folds are simply rock caverns, partly natural and partly artificial, often enlarged by a stone wall built outside it. It was the absence of these rock caverns on the east side of Jordan that compelled the Reubenites and Gadites to build folds for themselves, whereas on the opposite side places of refuge were comparatively abundant.

See, for example, the well-known history related in 1 Sam. xxiii.-xxiv. David and his miscellaneous band of warriors, some six hundred in number, were driven out of the cities by the fear of Saul, and were obliged to pass their time in the wilderness, living in the "strong holds" (xxiii. 14, 19), which we find immediately afterwards to be rock caves (ver. 25). These caves were of large extent, being able to shelter these six hundred warriors, and, on one memorable occasion, to conceal them so completely as they stood along the sides, that Saul, who had just come out of the open air, was not able to discern them in the dim light, and David even managed to approach him unseen, and cut off a portion of his outer robe.

That this particular cave was a sheepfold we learn from xxiv. 2-4: "Then Saul took three thousand chosen men out of all Israel, and went to seek David and his men upon the rocks of the wild goats. And he came to the sheepcotes by the way." Into these strongholds the Sheep are driven towards nightfall, and, as the flocks converge towards their resting-place, the bleatings of the sheep are almost deafening.

The shepherds as well as their flocks found shelter in these caves, making them their resting-places while they were living the strange, wild, pastoral life among the hills; and at the present day many of the smaller caves and "holes of the rock" exhibit the vestiges of human habitation in the shape of straw, hay, and other dried herbage, which has been used for beds, just as we now find the rude couches of the coast-guard men in the cliff caves of our shores.

The dogs which are attached to the sheepfolds were, as they are now, the faithful servants of man, although, as has already been related, they are not made the companions of man as is the case with ourselves. Lean, gaunt, hungry, and treated with but scant kindness, they are yet faithful guardians against the attack of enemies. They do not, as do our sheepdogs, assist in driving the flocks, because the Sheep are not driven, but led, but they are invaluable as nocturnal sentries. Crouching together outside the fold, in little knots of six or seven together, they detect the approach of wild animals, and at the first sign of the wolf or the jackal they bark out a defiance, and scare away the invaders. It is strange that the old superstitious idea of their uncleanness should have held its ground through so many tens of centuries; but, down to the present day, the shepherd of Palestine, though making use of the dog as a guardian of his flock, treats the animal with utter contempt, not to say cruelty, beating and kicking the faithful creature on the least provocation, and scarcely giving it sufficient food to keep it alive.

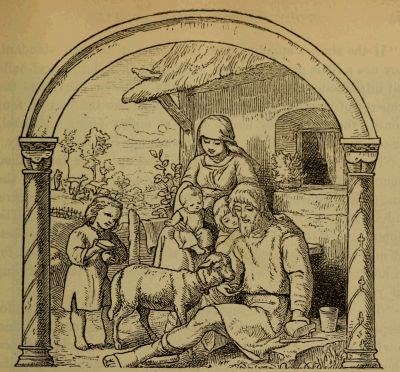

Sometimes the Sheep are brought up by hand at home. "House-lamb," as we call it, is even now common, and the practice of house-feeding peculiar in the old Scriptural times.

We have an allusion to this custom in the well-known parable of the prophet Nathan: "The poor man had nothing, save one little ewe lamb, which he had bought and nourished up: and it grew up together with him, and with his children; it did eat of his own meat, and drank of his own cup, and lay in his bosom, and was unto him as a daughter" (2 Sam. xii. 3). A further, though less distinct, allusion is made to this practice in Isaiah vii. 21: "It shall come to pass in that day, that a man shall nourish a young cow, and two sheep."

How the Sheep thus brought up by hand were fattened may be conjectured from the following passage in Mr. D. Urquhart's valuable work on the Lebanon:—

"In the month of June, they buy from the shepherds, when pasturage has become scarce and sheep are cheap, two or three sheep; these they feed by hand. After they have eaten up the old grass and the provender about the doors, they get vine leaves, and, after the silkworms have begun to spin, mulberry leaves. They purchase them on trial, and the test is appetite. If a sheep does not feed well, they return it after three days. To increase their appetite they wash them twice a day, morning and evening, a care they never bestow on their own bodies.

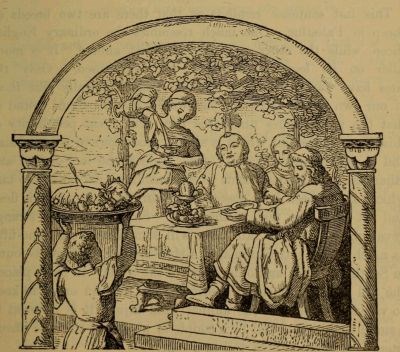

THE POOR MAN'S LAMB.

THE RICH MAN'S FEAST.

"If the sheep's appetite does not come up to their standard, they use a little gentle violence, folding for them forced leaf-balls and introducing them into their mouths. The mulberry has the property of making them fat and tender. At the end of four months the sheep they had bought at eighty piastres will sell for one hundred and forty, or will realize one hundred and fifty.

"The sheep is killed, skinned, and hung up. The fat is then removed; the flesh is cut from the bones, and hung up in the sun. Meanwhile, the fat has been put in a cauldron on the fire, and as soon as it has come to boil, the meat is laid on. The proportion of the fat to the lean is as four to ten, eight 'okes' fat and twenty lean. A little salt is added, it is simmered for an hour, and then placed in jars for the use of the family during the year.

"The large joints are separated and used first, as not fit for keeping long. The fat, with a portion of the lean, chopped fine, is what serves for cooking the 'bourgoul,' and is called Dehen. The sheep are of the fat-tailed variety, and the tails are the great delicacy."

This last sentence reminds us that there are two breeds of Sheep in Palestine. One much resembles the ordinary English Sheep, while the other is a very different animal. It is much taller on its legs, larger-boned, and long-nosed. Only the rams have horns, and they are not twisted spirally like those of our own Sheep, but come backwards, and then curl round so that the point comes under the ear. The great peculiarity of this Sheep is the tail, which is simply prodigious in point of size, and is an enormous mass of fat. Indeed, the long-legged and otherwise lean animal seems to concentrate all its fat in the tail, which, as has been well observed, appears to abstract both flesh and fat from the rest of the body. So great is this strange development, that the tail alone will sometimes weigh one-fifth as much as the entire animal. A similar breed of Sheep is found in Southern Africa and other parts of the world. In some places, the tail grows to such an enormous size that, in order to keep so valuable a part of the animal from injury, it is fastened to a small board, supported by a couple of wheels, so that the Sheep literally wheels its own tail in a cart.