Полная версия

Полная версияNature's Teachings

IT has long been known that Electricity, Galvanism, and Magnetism are but different manifestations of the same force, and that one can be converted into the other at will. It is also known that this wonderful and most important principle lies latent in everything, and only needs the proper machinery to evoke it.

The few following illustrations are intended to show its prevalence in Nature, and that human art does not create, but only makes manifest a power that exists, but lies latent until called forth.

Without going into details, which would occupy the whole of such a volume as this, I may mention that Electricity saturates all the material creation, and that even man himself is not only a reservoir of electricity, but that he feels positively ill if the normal amount be not supplied.

Take, for example, the hours that precede a thunder-storm. We feel languid and depressed. We cannot bring our thoughts together. We are almost incapable even of bodily labour. The reason is, that the portion of the earth on which we live has parted with some of its electricity, and has drawn it out of our bodies.

Then comes the welcome thunder-storm; clouds overcharged with electricity come to restore the balance. The lightning flashes from the clouds to the earth as soon as they are near enough; the rain falls, carrying with it stores of silent electricity; and in an hour or two all seems changed.

The air, which hitherto seemed to afford no nourishment to the lungs, is bracing and invigorating. The nervous system recovers its tension, and the brain can act without a painful effect. All Nature seems to put on a different aspect, and brightness and vigour take the place of dulness and languor.

By a strange coincidence, there is just such a lack of electricity as I am writing, and the barometer has rapidly sunk to such a degree that a storm seems inevitable.

One of the chief difficulties in dealing with such a subject as this is to know where to begin. We will, however, do our best to take a general view of it, without going into details.

Many centuries ago it was well known that amber, if rubbed with a dry cloth, would first attract, and then repel, various small and light substances. Indeed, the Greek word for amber, namely, Elektron, has given its name to the modern science of Electricity. Many other substances, such as glass, sealing-wax, &c., possess the same property.

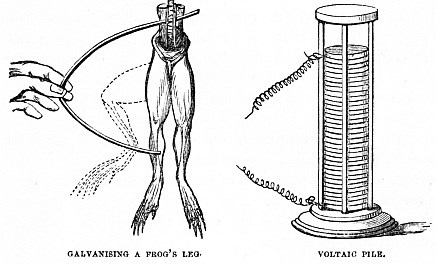

This frictional electricity is but transient, the electric fluid, if we may be allowed to use the term, being driven out by main force from the material in which it was latent, just as fire is procured by the friction of two dry sticks. There is, however, a form of Electricity called Galvanism, from its discoverer, Galvani, who, somewhere about 1790, discovered that the limbs of a dead frog might be excited to action by electricity applied to the nerves.

Afterwards, Volta of Pavia, from whom the Voltaic Pile is named, took up Galvani’s discoveries, and produced electricity without friction, by the contact of differently conducting substances.

The right-hand figure represents the Voltaic Pile. It is composed of a series of plates arranged in the following manner—Zinc, Silver, and Cloth, the whole being moistened with diluted acid. Copper will answer the purpose nearly as well as silver, and is not so costly. A very simple mode of demonstrating the presence of electricity is by taking a piece of zinc and a silver coin, and placing one below and the other above the tongue. If the two be then brought together, a very peculiar taste is perceived, and a sudden flash of light seems to pass across the eyes.

The illustration represents on the right hand the Voltaic Pile as at present made, and on the left are the two hind-legs of a frog, with the upper part of the nerves made bare for the purpose of experimenting. The dotted lines show the extent of the movements of the leg when the galvanic current is passed through the nerves.

Now we come to a plan whereby electricity can be accumulated, or locked up, so to speak, and be discharged at once with a definite shock instead of being poured away by degrees. This can be done in many ways, the most common being that which is known by the name of the Electric Jar. It is a glass vessel coated within and without with tin-foil, and having a metal rod passing through the cork in such a way that while the lower end is in contact with the inner coating of tin-foil, the other end is guarded by a ball.

Electricity is now poured into the interior of the jar, and, when contact is made between the inner and outer coatings, a sudden discharge takes place. If a number of persons hold each other’s hands, and those who form the two extremities touch the outer coating and the ball which communicates with the inner coating, a sharp discharge is at once made, passing through all the bodies, and inflicting a smart shock, especially at the elbows.

Similar effects can be produced with the Voltaic Battery, but, as that instrument has already been figured, the Electric Jar has been selected. Of course any number of such jars can be connected together, and the shock will be proportionately increased in intensity.

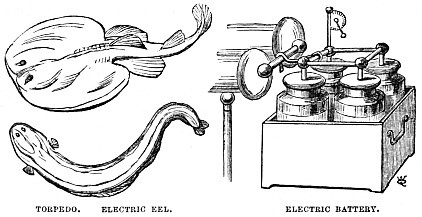

In Nature we have several-parallels. Putting aside the obvious one of a lightning-flash, which has already been mentioned, we pass to two remarkable examples of the capability of animal structure to produce electricity, to store it up, so to speak, and discharge it at will. Both these creatures are fishes, one belonging to the Skates or Rays, and the other to the Eels.

The upper figure on the left-hand side of the illustration represents the Torpedo, sometimes called the Cramp-fish, Numb-fish, or Electric Ray. Fortunately for us, it is but seldom found on our coasts, but it is tolerably common in the warmer parts of the world.

The electric organ in this fish is double, and so large that its shape can easily be recognised even through the skin. It is made up of a vast number of discs arranged upon each other in columns like the metallic portions of the Voltaic Pile, and separated from each other by delicate membranes, which take the place of the cloth. When I mention that more than eleven hundred columns have been found in a single Torpedo, and that each column contains several hundred discs, it may be imagined that the shock which such a creature can give must be a very powerful one.

The object of this power seems to be analogous to that of the venomous serpent, i.e. to enable the creature to secure its prey by either killing it or rendering it temporarily insensible by an electric shock. As if to show that the delivery of the shock is achieved by an exertion of will, observers have noticed that just before the shock is delivered, the eyes are depressed in the head like those of a toad when swallowing a large insect.

A still more powerfully electric animal is the Electric Eel of Southern America. It sometimes attains a length of six feet, and its electric organs are four times as proportionately large as those of the torpedo.

There is no doubt as to the object of the electric power of this eel, as I have often seen it kill fish, and then eat them.

When about to deliver its shock, it curves its body towards the intended victim, stiffens itself, and with a sort of shudder the electric fluid is emitted. The fish at which it is aimed never seems to escape, but, simultaneously with the shudder on the part of the Electric Eel, turns on its back and lies motionless until it is picked up by its destroyer.

Neither the Torpedo nor the Electric Eel has unlimited stores of electricity. If irritated into delivering repeated shocks, each discharge is less powerful than its predecessor, until at last the creature is almost wholly powerless, and must rest and recruit itself before it can lay up fresh stores of the electric fluid.

I may add that the electric spark has been obtained from both these fishes. It was only a small spark, but in such experiments a small spark is as satisfactory as a large one.

What are the channels by which the electric fluid is transmitted through our bodies?

They are the nerves, which convey from and to the brain a subtle fluid, if it may be so called, just as the arteries and veins convey blood to and from the heart. If any of these nerves be electrified, even after the death of the animal, or after the separation of a limb from the body, muscular movements are induced, and the limb moves as if instinct with life.

Without these nerves we should be unable to feel the severest shock, but they permeate the body so completely, that not a part of the skin can be pricked without a nerve being wounded.

It is by means of these conductors that the will is made to act upon the limbs. The mind, for example, desires the legs to walk, and they do so, the order being transmitted to them through the nerves.

As a rule, we are unconscious of this process. But, when paralysis takes place, and the nerves refuse to perform their functions, the will is absolutely useless, and, however desirous a man may be of walking, he cannot move a step if the nerves of his legs are paralyzed. In cases where the paralysis comes on slowly and in detail, the patient mostly becomes conscious of the part played by the nerves, and feels that his will can to a certain degree rouse the expiring powers of the nerve fluid.

This in its turn is but the conductor for another and infinitely more subtle fluid, of which our space will not allow us to treat, but which forms the connecting link between body and spirit. Perhaps some of my readers may have seen those curious preparations of the human form, when the arteries have been injected with red wax, and the veins with blue wax, and then the fleshy portions dissolved away by chemical means.

The result is a perfect human form, and even to the very tips of the fingers and toes the blood-vessels follow the contour of the body. Did we have means of injecting the nervous system, we should arrive at similar results, except that the nerves would be found infinitely more intricate than the veins and arteries. Thus a human being is a series of human forms, interwoven with each other, and mutually dependent on each other.

It is curious to see how the great discoveries of modern days have but copied Nature.

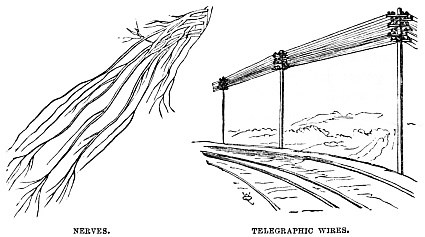

Take, for example, the network of telegraphic wires which is day by day spreading itself over the surface of the earth, and the parallel will at once be visible. Just as the brain transmits its message to the limbs by means of the nerves, so does the same brain transmit its message through thousands of miles, by utilising the wires which are but the rough and coarse imitations of the wonderful nervous system of the human frame.

The illustration shows the parallelism as well as can be done by a mere chart.

On the left-hand side is shown the manner in which a nerve-group is distributed to different parts of the body. On the right the railway telegraph wires are seen, and, as the reader will probably remember, branch wires are carried into the signal boxes, just as branch nerves are carried to the most distant parts of the body.

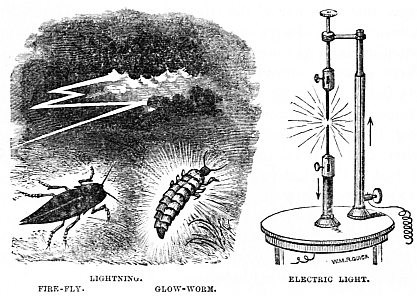

I have already mentioned the Electric Spark, and that it is, in fact, a miniature lightning-flash, the little crackling report being a miniature thunder-clap. It can be produced by frictional electricity, or by the voltaic pile in its many variations, or by animal substances alone, as in the case of the torpedo and electric eel.

We now come to a modification of the spark, whereby a continuous current of electricity is sent through two charcoal points, and inflames them with such intensity that the eye cannot look upon its dazzling whiteness. There is none of the yellowness about it which is so great a drawback to our artificial lights, whether they be gas, candle, or lamp, and which makes ladies’ dresses that are really beautiful by day look dull and almost ugly by night.

It is wonderful to see how the Electric Light kills all other lights. The brightest gas becomes dull, and its shadow is thrown on the wall which it formerly illuminated, and the most delicate tints of silks and satins suddenly display themselves in the blinding whiteness of the Electric Light.

At present it is too costly to be brought into common use, but its intensity is so great that serious ideas have been formed of dispensing with street lamps altogether, and illuminating towns with a few electric lamps placed at a considerable height, and having their beams reflected downwards.

London is thought to be a specially fit subject for this mode of lighting, as the electric beams can pierce the fogs which the gas-lamp only augments, and give the traveller some hope of finding his way through the most familiar streets.

In the illustration the right-hand figure represents the Electric Light as at present in use. The upper portion of the left-hand side represents the forked lightning, whose dazzling whiteness is so familiar to us, even in the noon of a summer’s day.

Below are shown the Fire-fly of warm climates, and the Glow-worm, which, in our comparatively cool country, cheers the summer evenings with its pale lamp. As to the source of this mysterious light, which burns without producing heat sufficient to be recognised by our most delicate instruments, we know but little.

There are instruments so infinitely more sensitive than the best thermometer, that they will record instantaneously an increase of heat if a human being passes in front of them, though at several yards’ distance. Yet no effect is produced on them by any of the Fire-flies or the Glow-worm. The spectroscope itself gives little or no information, the spectrum of the light being without bands or bars, and being what is technically called a “continuous” spectrum.

Last year I tried numbers of Glow-worms with the spectroscope, and always with the same result. I never saw the Fire-flies alive, but, no matter what may be the colour of the light, the spectrum, whether of the Glow-worm or any of the Fire-flies, seems to be always continuous, and so to give but little information as to its source.

There appears, however, to be little doubt that animal electricity is the real cause of this curious phenomenon, and that the force which is expended in the torpedo and electric eel, in giving shocks accompanied by slight electric sparks, may develop itself in these insects by producing a continuous light. And just as the electric fishes can emit or withhold the shock as they please, so can the Fire-flies and Glow-worms give out or retain the light by which they are so well known.

Then we come to the multitudinous luminous inhabitants of the sea, which, as many of my readers have probably seen, convert the waves into rolling masses of living fire.

MagnetismNow we come to another condition of electrical force, called Magnetism.

One form of it is strongly developed in the Loadstone, an ore of iron. This ore has the property of turning east and west when suspended freely, it attracts any object made of iron, and can communicate its powers to iron by merely stroking it. There is in the Museum at Oxford a splendid specimen of the Loadstone, which has imparted its virtues to thousands of iron magnets, and has lost none of its virtues by so doing.

All bodies are now known to be magnetic in some way or other. Several, such as iron, nickel, and one or two other metals, turn north and south when suspended on a pivot, but the great bulk of other bodies turn east and west, and are called Diamagnetics.

As we all know, the property of turning north and south has been utilised in the Compass, without which modern science would be paralyzed, and travel rendered impossible.

It is worthy of notice that although the magnetic needle of the compass turns to the north, it does not do so because it is attracted by the north pole, but because it is repelled from the east and west.

We have long known that if a current of electricity be sent round a magnetic needle, the latter at once turns at right angles to it. On this principle depends the Electric Telegraph. When communication is made by using the handles, a current of electricity is sent round the needles, and causes them to turn at right angles until stopped by a little ivory pin, which prevents them from overshooting themselves.

There is a perpetual stream of electricity passing over the earth from east to west, and in consequence all magnetic bodies are forced to turn at right angles, just as is the case with the magnetic needle.

CHAPTER XVI.

TILLAGE.—DRAINAGE.—SPIRAL PRINCIPLE.—CENTRIFUGAL FORCE

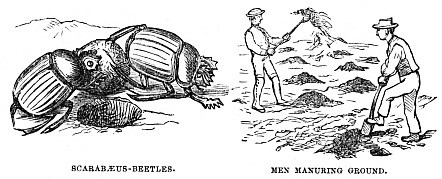

Systems of cultivating Ground.—The Fallow System.—Manuring the Ground.—Custom of China.—Nature’s Abhorrence of Waste.—What becomes of Dead Animals.—Burying-beetles.—The Scarabæus-beetles and their Work.—Drainage versus Sewage.—Clay Soils and Drains.—The Mole, the Earth-worm, Rats, Mice, and Rabbits.—The Flexible Drain and the Lobster’s Tail.—The Turbine Pump and the Ascidian.—The Spiral Principle.—The Smoke-jack, Kite, and Wings of Birds.—Centrifugal Force.—Revolution of Planets.—The “Governor” of the Steam-engine.—The Sling, Amentum, and Mop.—The Gyroscope, the Bicycle, and the Hoop.

SEVERAL times, in the course of this work, we have touched upon man’s dealings with the earth, such as mining and tunnelling. We will now take another side of the same question, and, in connection with Tillage, consider Drainage, whereby superabundant moisture is removed from the earth, and Manuring, whereby the exhausted soil is renovated.

We will take this subject first.

It has long been known that it is impossible to get more out of the ground than exists in it, and that when the soil has been so worked as to become unproductive, there are only two remedies. The one is to allow the ground to remain uncultivated for a time. It must be ploughed in deeply, as if it were to be sown with a crop, and must be left to recruit itself from the air. This is the now abandoned “fallow” system, which used to be in full operation when I was a child.

As, however, population increased, and with it the perpetually increasing demand for food, land was found to be too precious to be allowed to lie fallow and idle. Then came the system of rotation of crops, potato following wheat, clover following potato, &c. But, above all, agriculturists learned that in the long-run there is nothing so cheap as manure, i.e. the return to the soil by animals of the elements which these animals took out of it.

On the right hand of the illustration (page 495) is shown the simplest mode of enriching the soil, namely, by spreading the manure on the surface of the earth, and then digging it in. Any mode of thus enriching the earth is a proof of civilisation. No savage ever dreamed of such a thing, and I doubt whether barbarians recognised the principle at any time.

Nowadays we have recognised the necessity of returning to the soil in one form the elements which we have taken from it in another. As usual in such arts of civilisation, the Chinese have long preceded us. They waste nothing, carrying, perhaps, its principles to an extent which scarcely suits our European ideas.

They even utilise the little clippings of hair, to which every Chinaman is almost daily subject, if he wishes to keep up his self-respect in public. The barbers carefully preserve these clippings, and sell them to gardeners. They are too precious to be used in general agriculture, but the flower artist, when he plants the seed, puts in the same hole a little pinch of human hair, knowing it to be a strong stimulant to growth.

Without multiplying examples of artificial manuring, most of which are too familiar to need description, we will proceed to the methods by which Nature has for countless centuries achieved the same work that Man has lately learned to undertake.

Nature abhors waste, and in the long-run will prove it, however wasteful may be the ways of her servants. Take, for example, the case of an ordinary tree, such as an elm, an oak, or a birch. In the autumn the leaves fall. In the next summer scarcely a dead leaf can be found. They have been decomposed by rain, dews, and gases, and have thus returned to the earth more than the nutriment which they took out of it.

Here man is apt to interfere. Knowing the invaluable productive powers of decayed leaves, he removes them as they fall, and stores them in heaps so as to form the costly, but almost indispensable, “leaf mould.” In so doing, however, he deprives the trees of their natural nutriment, and by degrees they dwindle and die.

Nature, in this case, shows her superiority over Art.

Then we have the remarkable fact that millions of animated beings die annually, and no vestige of their remains is found. Hyænas and vultures might account for a few bodies, the remnants of which have been found in ancient caverns. But there is no hyæna which could crush the leg bones of an adult elephant; and yet I suppose that neither in Africa nor Asia has any one discovered the body of an elephant or rhinoceros that had died a natural death.

In the first place, there is the curious point, which I have already mentioned, and which is shared by nearly every race of human savages, that when an animal feels that it has received its death-stroke, it accepts the conditions, withdraws itself from those who yet have life in them, and yields up its life as calmly as if it were but sleeping.

But what becomes of the body? As to such enormous beings as elephants, the various species of rhinoceros, and whales, which are as large as several elephants, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus put together, I cannot say from practical knowledge.

Still, as size is only comparative, the rule that holds good with a small animal may hold equally good with a large one. It is my lot to walk very often upon the banks of the Thames. It is a charming walk at high water, but at low water there is too much odoriferous mud, and there are too many dead dogs and cats to make it an agreeable resort, except for enthusiastic entomologists, who seem to swarm in this neighbourhood.

Scarcely has such a carcass been stranded than it is beset by Burying-beetles of various kinds. Hundreds upon hundreds can be shaken out of the corpse of a dog or cat, and, before the next tide has come up, there is scarcely any flesh left on the bones, it having been dug into the earth by the Burying-beetles.

Then there is that wonderful family of Scarabæus-beetles, which do us invaluable service as scavengers and agriculturists. They follow the path of the caravans, and effectively cleanse the course which has been traversed. Even man is obliged to utilise as fuel the droppings of the horses, cows, and camels; but the Scarabæus goes further, collecting all that man does not need, and burying it in the earth.

The instinct of the female Scarabæus urges it to gather together the rejecta, to form them into balls, placing an egg in the middle of each ball, and to bury them in the ground. Thus a double object is attained, the offensive substances being removed from the surface of the ground, where they do harm, and being transferred below the surface, where they do good.

Even the curious instinct of the dog, which leads it to bury bones, &c., which it cannot consume, and which it often forgets, if well fed, leaves them to be consumed by the all-absorbing earth.

It is evident that, in the end, the earth must receive back again that which has been taken from it. If, for example, we follow the present most wasteful plan of drainage, and fling into rivers everything which ought to be utilised on land, it only gets into the sea in the end, and in the course of years is decomposed, and returns to the earth in the form of gases. Meanwhile, however, we have robbed the locality, deprived it of the nourishment which it required, and forced ourselves to supply it elsewhere at a costly rate.