Полная версия

Полная версияNature's Teachings

Then we have those which are applied to our garments, such as the ordinary clothes-brush, the velvet-backed hat-brush, and the three kinds of boot-brushes.

In architecture, again, we should be very badly off without the painting-brushes, the whitewasher’s brush, and the paper-hanger’s brush; not to mention the exceeding variety of brushes used by artists both in oil and water colours.

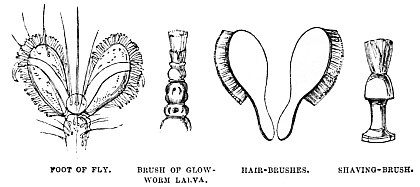

As to brushes applied to our persons, we have an infinite number of them. There is, of course, the hair-brush, without a pair of which, one for each hand, no one with a respectable head of hair could be expected to be happy.

We may add to this the revolving brush worked by machinery, which is to be found in the rooms of any respectable hairdresser, and which is a sort of an apotheosis of the Hair-brush, especially when it is worked, as in some places, by the electrical engine.

Then there is the shaving-brush, once an absolutely necessary article in a gentleman’s dressing-case, and above all requisite if the owner should happen to be a clergyman. Nowadays, shaving is rapidly decreasing, and of all the professions, those who are most largely bearded, both in number of beard-wearers and dimensions of the beard, are to be found among the clergy.

Then there are any number of tooth-brushes for the interior of the mouth, and of flesh-brushes, with or without handles, for the service of the bath. There are even gardeners’ brushes, for the purpose of clearing the plants of the aphides, or green-blight, as these insects are popularly called by gardeners. So it will be seen that—absurd as the proposition may appear at first sight—we may really accept the use of the brush as a safe test of the progress of civilisation.

We will now glance at the illustrations of this subject.

On the right hand is depicted the once honoured Shaving-brush, the terror of all stiff-bearded men on frosty mornings, and yet clung to with a strange inconsistency. Many years ago a military member of the House of Commons was sensible enough to wear his beard, and was, in consequence, the butt for interminable jokes. At the present time, if the House were counted, a great majority of the younger, and not a few of the older, members will be found to wear either the beard or moustache, or both.

Perhaps some of my readers may object that many nations in a state of very partial civilisation are accustomed to shaving. So they are, but they do not use the shaving-brush. Most of them content themselves with pulling out the hairs by the roots, while others merely saturate the hair with hot water, and so need no brush.

Next to the shaving-brush is drawn a pair of ordinary Hair-brushes, such as have been mentioned.

Passing to the left, we find an object which bears a curious resemblance to the shaving-brush. This is an apparatus belonging to the larva or grub of the Glow-worm. This creature feeds upon snails, and, in consequence, gets itself covered with the tenacious slime. In order to enable it to rid itself of this inconvenience, the larva is furnished near the end of its tail with the curious apparatus which is here shown. It consists of some seven or eight soft white radii, arranged so as to produce a brush-like outline, and being capable of extension or withdrawal at will.

It had long been known that this “houppe nerveuse,” as it is called, was employed as an assistant in locomotion; but until comparatively late years—I believe about 1826—no one seemed to be aware that it was used as a brush. Its functions as a brush may be compared with the somewhat similar offices fulfilled by the pincers of the Earwig, as mentioned on page 259.

Next to the brush of the glow-worm larva is shown one of the fore-feet of the ordinary house-fly, much magnified. Passing, as irrelevant to the present subject, the use of the feet as organs of locomotion, we may take them as being used for the purpose of cleansing the body of the insect.

I suppose that none of my readers has been sufficiently inobservant not to have noticed the way in which a fly cleanses itself, behaving almost exactly like a cat under similar circumstances. The fore-feet are repeatedly passed over the head, which is bowed down to meet them, while a similar office is performed for the rest of the body by the hind-legs. The feet are then rubbed against each other, so as to free them from all accumulations, just as the housemaid cleanses the hair-brush with the comb before washing it. So mechanical is this process, that a fly has been known to go through it even after it had been deprived of its head.

The reader will see, on reference to the illustration, that the two sharp and curved claws are capable of answering the purpose of combs, and, indeed, are so employed.

CombsWe will now proceed to the Comb, and see how Art has been anticipated by Nature.

As long as human beings possess hair upon their heads, whether it be the short, frizzed, woolly pile of the negro, the thick, coarse crop of the Fijian, the coarse, straight hair of the Mongolian, or the long and fine hair of the Georgian races, they must, as soon as they attempt any kind of civilisation, form some instruments by which the hair can be dressed. The simplest machine for this purpose is the Comb, and I possess many varieties of this article, suitable to the different races for whom it was made.

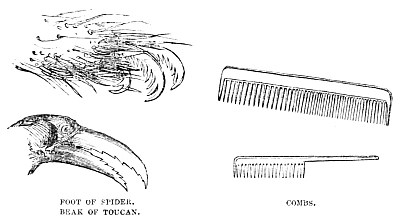

Putting aside the ordinary Combs of our European civilisation, such as are given in the illustration, there are many others which are modified according to the use which they have to fulfil.

The simplest is the Comb of the celebrated Amazon regiment of Dahomey. This is nothing but a slight skewer of ivory, some ten inches in length, and amply sufficient for arranging the short woolly lumps which do duty for hair on the head of a true negro. One of these very primitive combs is in my collection, together with an undress costume of the Amazon in question, and both being very much suited to each other. The comb being a simple skewer, the dress is only a few thongs of leather, but they are both equal to the requirements of their wearers.

As much time would be lost in combing the hair with a single skewer, especially when that hair belonged to any but the pure negro races, a simple but obvious improvement was introduced. A number of skewers were lashed together side by side, with their ends a little diverging, and thus was formed the germ of our present Combs.

As to the varieties of the Comb, they are simply endless; and whether they are intended, in the form of the Currycomb, to smooth the harsh coat of a horse, or, as a small-tooth Comb, to search the hair of the young, they are all based on one principle.

It is really curious to see how often two men, who cannot possibly have seen each other, will hit upon the same idea, not only simultaneously, but often in the very same words. So it is with regard to the Comb. In no two parts of the world can the natives be more opposed to each other than is the case with Fiji and Western Africa; yet I possess specimens of combs from both countries, made on the same principles, and so exactly in the same manner, that, except for the coarseness of the African Comb, it would be almost impossible to distinguish between them. There is but a slight difference in the size and shape of the two combs, and yet nothing can be more distinct than the characters of the two nations.

I have also a Japanese Comb of the most ingenious construction. It is made of wood, and cut exactly like our double ivory small-tooth comb; but it is furnished with a curious kind of handle, consisting of a flat piece of wood with a deep longitudinal slit, into which either side of the comb fits; and so beautifully is it made, that when it is fitted upon either side of the comb it looks as if handle and comb had been cut out of the same piece of wood.

The Fijian Combs are much after the same fashion as those of Western Africa, except that, with the artistic nature of their kind, the Fijians, instead of merely lashing together the numerous spikes of which the comb is made, employ a variety of patterns, and seem to luxuriate in the exuberance of artistic spirit which can make hundreds of combs, and no two of them alike.

On the left hand of the illustration are two examples of Natural Combs which are well worthy of notice. The upper one is a foot of the common Garden Spider (Epeira diadema), which has been several times mentioned in this work in connection with different subjects.

Every one who has watched the life of one of these creatures must have noticed how often its hairy body becomes clogged with little bits of its own web, and how dexterously it releases itself from such encumbrances. The figure in the illustration shows how this can be done, the strangely formed foot acting at the same time the part of comb and brush. It will be seen that the curved spikes of the claws act as a comb, while the bristle-like hairs discharge the duty of a brush.

Not only are these projections used as Combs, but as appendages which insure the security of footing along the lines of the web. The reader will easily remember that when a Spider rushes along its web to secure its prey, it always runs along one of the radiating lines, which have no viscid drops, and that it never misses its hold. The latter point is secured by the structure of its claws, which are so made that if one projection misses the line, another is sure to fasten upon it. Some years ago, while watching “Blondin” go through his wonderful performances, I was especially struck with the pattern on which he had constructed the stilts upon which he traversed the rope. They were made in the most exact imitation of the Spider’s foot, and though it is not probable that he borrowed them from that object, the resemblance was so close that he might readily have done so.

Below the spider’s foot is given the head of a Toucan, one of those beautifully coloured and large-billed birds that inhabit tropical America. These birds are very particular about their plumage, and even when in captivity dress their feathers with the utmost care. When they do so, the saw-like notches of the beak act the part of a comb, and the fibrils of the feathers are by their action dressed parallel to each other, and give to the whole bird its proper appearance of health.

I may here mention that there is one comb in Nature, the use of which has never been clearly ascertained. This is the remarkable organ found in the Scorpion, and simply known as the “comb.” There are two of them, one on each side of the under surface. Their colour differs slightly according to the species, but is generally a light yellow brown. The number of teeth also differs extremely, for in the Rock Scorpion there are only thirteen teeth, while in the Red Scorpion there are twenty-eight.

Buttons, Hooks and Eyes, and ClaspHaving now treated of brushes and combs as articles belonging to the toilet, we will proceed to those which belong to the dress rather than the person. It is a curious fact that, as far as is known, buttons and hooks belong only to advanced civilisation. The simplest garment is, of course, a cloth of some material wrapped round the waist, and, as we see in the wonderful Egyptian paintings which have survived their painters some three thousand years, the simple fold can retain its grasp round the loins, even through the exertions of a long day’s work.

I was always at a loss, when looking at these drawings, to understand how a single fold could retain so simple a garment in its place, but when I made my first visit to the Hammam Turkish Bath in Jermyn Street the mystery was at once solved. The “check,” as it is there called, is long enough to pass about once and a half round the waist of an ordinary man. One end of it is placed on the left side, so as to bring the lower edge on a level with the knee. It is held by the left hand until the right hand passes it round the waist. It is then turned over in a broad single fold, and will remain in position for hours, the left leg having free scope between the two ends, and yet not being needlessly exposed.

Next to the simple fold comes the tie, which is in use all over the world. The chief object of a good Tie is that it should retain its hold as long as needed, be loosened with a touch in necessity, and, as a matter of consequence, should never “jam.”

Still, even the best of ties are liable to objection. I once heard an argument on the subject of ties and buckles with regard to shoes. The speakers were both Derbyshire men, and their phraseology was somewhat obscure. However, both stuck to his own principles, one saying that “when a shee-uew is boo-oo-oockled, it’s boo-oo-ookled;” and the other asserting, in equally strong terms, that “when it’s tee-ee-eed, it’s tee-ee-eed.”

The buckle was here asserting its supremacy in civilisation over the tie, and was palpably right. Any one, so rose the argument, can tie two strings together, but the structure of the buckle is too complicated to be understood, much less invented, by any uncivilised being.

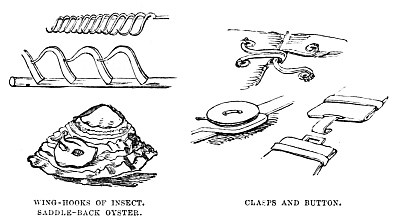

Next come, in natural order, the Button and the Clasp, each being identical in principle. In the case of the former the “eye” is placed over the button, while in the latter the clasp or hook is passed through the eye. Several examples of the Button and the Clasp are given on the right hand of the illustration, and are too familiar to need description.

As to the corresponding articles in Nature, they are very numerous. We will take, for example, the Saddle-back or Crow Oyster of our own shores. It is a most remarkable being. It deposits upon the object to which it adheres a sort of button of shelly matter, and the lower valve, which is nearly flat, has in it an aperture which is placed over the knob, just as a button-hole goes over the button. As this arrangement is confined to the lower valve, and cannot be seen unless the upper valve be removed, the lower valve only is shown in the illustration, as it appears when fastened to the side of a large limpet.

Of the Hooks and Eyes in Nature I have only taken two examples, though there are many others.

We all know the Bees, Wasps, Hornets, and other similar insects, and that they possess four wings. I may here mention that no insect which does not possess four transparent wings is capable of stinging.

When the insect is at rest the four wings may be easily distinguished, but when it is in flight they coalesce, so that practically the insect has two wings instead of four. This object is attained in the following way:—

The lower edge of the first pair of wings is turned over in a rather stiff fold. The upper edge of the second pair of wings has a row of small, but strong and elastic hooks. When the insect is about to fly, the hooks are hitched into the fold, and so the wings are fastened together. These hooks are shown in the illustration, and the reader will easily see how effective they must be in their operation. An almost exactly similar structure is found in the feathers of birds, and it is by means of these tiny hooks that wings are enabled to present a continuous, light, and elastic surface in the air.

CHAPTER IV.

THE STOPPER, OR CORK.—THE FILTER

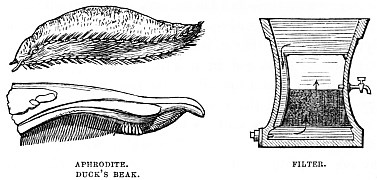

Vessels and their Covers.—Corks.—Mode of bottling Wine.—Conical Corks and Stoppers.—Self-fitting Candles.—Candle-fixers.—The Vent-peg.—The Blow-guns and their Missiles.—The Serpula and its Conical Stopper.—The Filter.—The Bosjesman procuring Water.—How to make a simple Filter.—The Earth as a Filter.—The Sea-mouse, or Aphrodite, and its filtering Apparatus.—The Duck’s Beak, and its beautiful Structure.—The Jaw of the Greenland Whale.—Fork-grinder’s Respirator.—How Insects breathe.—Spiracles, and their general Structure.—Spiracle of the Fly.—Experiment upon a Cockroach, and its Result.

The Stopper, or CorkTHIS object, as depicted in the illustration, is a product of civilised life, though, as soon as a savage could make a vessel, he seems to have made a Cover for it if it were of large diameter, or a Stopper if the opening were small. Even the very Bosjesman, who is quite unable to make a clay vessel, and uses empty ostrich eggs by way of water-bottles, is yet capable of making plugs with which he can stop up the apertures. Then the Kafir, with his gourd vessels, whether they be for water or snuff, makes a plug that fits tightly enough to exclude the air, as well as to retain the contents.

The invention of glass bottles necessarily brought with it the introduction of a new kind of plug, and a material for such a plug was found in the bark of the cork-tree, a species of oak. This bark possesses the capability of compression to a very great extent, and, being highly elastic, it expands as soon as the pressure is removed.

Thus, in bottling wine, the corks are always made much too large to go into the mouths of the bottles. They are first dipped in a cup containing the same wine, and are then compressed violently by a machine worked by a handle, and which, being practically a powerful pair of nut-crackers with a rounded gripe, must suit the shape of the cork. It is then taken out of the machine, and, before it has had time to expand, is rapidly fitted to the neck of the bottle, and driven home with a wooden mallet. Expansion then takes place, and the bottle is rendered air-tight, so that no damage is done to the wine.

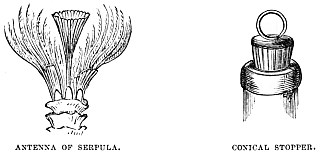

If the whole of the wine were to be drunk when the cork was removed, this plan would be amply sufficient. But there are many cases where the bottle is opened, and only part of the wine consumed. To re-cork the bottle would be too troublesome, and to leave it uncorked would spoil the wine. So the Conical Stopper was invented, which fits the neck of any ordinary wine-bottle, according to the depth to which it is introduced, and, by a slight screwing movement, sufficient compression is obtained to render the bottle air-tight. One of these Conical Stoppers is shown in the illustration on page 352. Sometimes they are made of cork, and sometimes of india-rubber; but the principle is the same in either case.

Perhaps some of my readers may have seen the Self-fitting Candles, which require no paper to make them fit the candlestick. These are enlarged at the base, which is made in a conical form, and slightly grooved. The “Candle-fixers” that are so much in use at the present day are made exactly on the same principle, being hollow cones of paper, which take the place of the solid cone.

The Vent-peg of casks is another instance of the cone used as a stopper.

Another example is to be found in the Blow-guns and Arrows of tropical America. In some districts the base of the arrow is fitted with a conical appendage of light cotton, rather larger than the tube, but capable of compression, so that it exactly fits the tube when pressed into it. In other districts the cone is hollow, and made of some thin and elastic bark.

Some years ago one of our most eminent gun-makers hit upon the same idea while making improved missiles for the game of “Puff and Dart,” and very much surprised he was when I showed him the South American arrow, not only with the same hollow cone at the base, but having also spiral wings along the shaft, so as to give it a rotatory motion as it passed through the air. The hollow cones of his darts were made of india-rubber, but the shape of the two was identical.

If the reader will refer to the left-hand figure of the illustration, he will see a beautiful example of the Conical Stopper as existing in Nature.

This is the “Stopper,” as it is popularly called, and, scientifically, the “infundibuliform operculum.” I prefer the former term myself, as being less liable to misapprehension.

The Serpula lives in a shelly tube of its own construction, and has the power of protruding itself when it desires to obtain food, and of withdrawing itself within the tube when alarmed. This movement is performed so rapidly, that the eye can scarcely follow it, and the mechanism by which it is done has already been described when treating of War and Hunting.

When it withdraws itself, the Stopper closes the mouth of the tube with perfect exactness, so as to leave the inhabitant in safety. The reader will see, on referring to the illustration, how exactly similar is the Conical Stopper of Art to that of Nature, and how the inventor of that article, as well as of the self-fitting candle, the candle-fixer, the blow-gun arrow, and the vent-peg, might have found prototypes of their inventions in Nature, if they had only known where to look for them.

The FilterEven in a state of uncivilisation man has been driven to invent a Filter of some kind.

The simplest kind of Filter is that which is used by the Bosjesman women when procuring water for the use of their families. When, as often happens, the only water to be obtained is to be found in muddy pools which have been trampled and perturbed by thirsty animals, the women have recourse to a simple, though rather repulsive, expedient.

Each woman is furnished with empty ostrich egg-shells by way of water-vessels, and she also takes a couple of hollow reeds. Over the end of one of these reeds she ties a bundle of grass, and then plunges it as deeply as she can into the mud. After a little while she sucks up the water through the tube, the grass acting as a filter, and she then discharges it by the second tube into the egg-shells. In this way the women will obtain water, where none but themselves could have procured it. As to the repulsive mode of obtaining it, no one can be fastidious when dying of thirst. Sir S. Baker mentions that when he was on his travels he managed in a halt to save up enough water for a bath for himself and his wife. He was about to throw away the soapy water, when the vessel was snatched from his hands by two of his attendants, and the contents eagerly drunk.

The different varieties of the Filter which we use at the present day are too familiar to need description. Whether they be made principally of charcoal, which is a powerful disinfectant, or of merely stones, gravel, and sand, they are all constructed on the same principle, namely, the straining out solid substances, and allowing only the pure water to pass through the interstices.

As to the Filters of Nature, they are almost innumerable. In the first place, the Earth itself is the primary filter of all, taking into itself all kinds of decomposing substances, separating them for the use of vegetation, and delivering the pure, bright, and sparkling spring water which we so highly and rightly value. The whole human body, again, is practically a collection of the most elaborate and effective filters that the mind of man can conceive. But we will pass to the more obvious examples of filters as seen in animal life.

On the upper left-hand portion of the illustration may be seen a long, fat, hairy creature, called popularly the Sea-mouse, and known to zoologists as Aphrodite aculeata. Although it inhabits the mud—and sea-mud is about as noisome a substance as can be imagined—it is clothed with a garment of such beauty that the rainbow itself can scarcely rival, and not surpass it. The hairs with which it is so profusely covered glitter and sparkle with every imaginable hue, among which red and green seem to be predominant.

These hairs occupy the sides of the body, but in the upper surface there is a thick coating of felted hairs, interwoven with each other so closely that they can with difficulty be separated. These hairs form a natural filter, strain away the mud from the water, and allow the latter to pour itself upon the organs of respiration. If, therefore, a specimen be examined when it is first brought up by the dredge, the felted hair will always be found to contain a considerable amount of mud, and much washing is needed before the creature can be introduced into an aquarium where the water is intended to be transparent.

I may here mention that the name of Aphrodite is a singularly happy one. It signifies something that arises from the foam of the sea, and was given to the goddess of beauty, because in the ancient myths she was said to have sprung from the foam of the sea. Unpoetical as it may appear, the German word Meerschaum, which is so familiar to us in connection with pipes, is the exact equivalent of Aphrodite.