Полная версия

Полная версияHardy Perennials and Old Fashioned Flowers

Besides by seed, which should be sown as soon as ripened, it may be propagated by root divisions at the time the crowns are pushing in spring.

Flowering period, June and July.

Primula Vulgaris Flore-pleno

Double-flowered Primrose; Nat. Ord. PrimulaceæIt is not intended to descant upon, or even attempt to name, the many forms of Double Primrose; the object is more to direct the attention of the reader to one which is a truly valuable flower and ought to be in every garden. Let me at once state its chief points. Colour, yellow; flowers, large, full, clear, and sweetly scented, produced regularly twice a year; foliage, short, rigid, evergreen, handsome, and supporting the flowers from earth splashes. Having grown this variety for five years, I have proved it to be as stated during both mild and severe seasons. It seems as if it wanted to commence its blooming period about October, from which time to the severest part of winter it affords a goodly amount of flowers; it is then stopped for a while, though its buds can be seen during the whole winter, and when the longer days and vernal sunshine return, it soon becomes thickly covered with blossoms, which are of the most desirable kind for spring gathering.

Its flowers need no further description beyond that already given; but I may add that the stalks are somewhat short, which is an advantage, as the bloom is kept more amongst the leaves and away from the mud. The foliage is truly handsome, short, finely toothed, rolled back, pleasingly wrinkled, and of a pale green colour. It is very hardy, standing all kinds of weather, and I never saw it rot at the older crowns, like so many of the fine varieties, but it goes on growing, forming itself into large tufts a foot and more across.

It has been tried in stiff loam and light vegetable soil; in shade, and fully exposed; it has proved to do equally well in both kinds of soil, but where it received the full force of the summer sun the plants were weak, infested with red spider, and had a poorer crop of flowers. It would, therefore, appear that soil is of little or no importance, but that partial shade is needful. It is not only a variety worth the having, but one which deserves to have the best possible treatment, for flowers in winter—and such flowers—are worth all care.

Flowering periods, late autumn and early spring to June.

Pulmonarias

Lungworts; Nat. Ord. BoraginaceæIn speaking of these hardy herbaceous perennials, I should wish to be understood that the section, often and more properly called Mertensia, is not included because they are so very distinct in habit and colour of both flowers and foliage. Most of the Pulmonarias begin to flower early in March, and continue to do so for a very long time, quite two months.

For the most part, the flowers (which are borne on stems about 8in. high, in straggling clusters) are of changing colours, as from pink to blue; they are small but pretty, and also have a quaint appearance. The foliage during the blooming period is not nearly developed, the plants being then somewhat small in all their parts, but later the leaf growth goes on rapidly, and some kinds are truly handsome from their fine spreading habit and clear markings of large white spots on the leaves, which are often 9in. or 10in. long and 3in. broad, oblong, lanceolate, taper-pointed, and rough, with stiff hairs. At this stage they would seem to be in their most decorative form, though their flowers, in a cut state, formed into "posies," are very beautiful and really charming when massed for table decoration; on the plant they have a faded appearance.

Many of the species or varieties have but slight distinctions, though all are beautiful. A few may be briefly noticed otherwise than as above:

P. officinalis is British, and typical of several others. Flowers pink, turning to blue; leaves blotted.

P. off. alba differs only in the flowers being an unchanging white.

P. angustifolia, also British, having, as its specific name implies, narrow leaves; flowers bright blue or violet.

P. mollis, in several varieties, comes from North America; is distinct from its leaves being smaller, the markings or spots less distinct, and more thickly covered with soft hairs, whence its name.

P. azurea has not only a well-marked leaf, but also a very bright and beautiful azure flower; it comes from Poland.

P. maculata has the most clearly and richly marked leaf, and perhaps the largest, that being the chief distinction.

P. saccharata is later; its flowers are pink, and not otherwise very distinct from some of the above kinds.

It is not necessary to enumerate others, as the main points of difference are to be found in the above-mentioned kinds.

All are very easily cultivated; any kind of soil will do for them, but they repay liberal treatment by the extra quality of their foliage. Their long and thick fleshy roots allow of their being transplanted at any time of the year. Large clumps, however, are better divided in early spring, even though they are then in flower.

Flowering period, March to May.

Puschkinia Scilloides

Scilla-like Puschkinia, or Striped Squill; Syns. P. Libanotica, Adamsia Scilloides; Nat. Ord. LiliaceæAs all its names, common and botanical, denote, this charming bulbous plant is like the scillas; it may, therefore, be useful to point out the distinctions which divide them. They are (in the flowers) to be seen at a glance; within the spreading perianth there is a tubular crown or corona, having six lobes and a membranous fringe. This crown is connected at the base of the divisions of the perianth, which divisions do not go to the base of the flower, but form what may be called an outer tube. In the scilla there is no corona, neither a tube, but the petal-like sepals or divisions of the perianth are entire, going to the base of the flower. There are other but less visible differences which need not be further gone into. Although there are but two or three known species of the genus, we have not only a confusion of names, but plants of another genus have been mistaken as belonging to this. Mr. Baker, of Kew, however, has put both the plants and names to their proper belongings, and we are no longer puzzled with a chionodoxa under the name of Puschkinia. This Lilywort came from Siberia in 1819, and was long considered a tender bulb in this climate, and even yet by many it is treated as such. With ordinary care—judicious planting—it not only proves hardy, but increases fast. Still, it is a rare plant, and very seldom seen, notwithstanding its great beauty. It was named by Adams, in honour of the Russian botanist, Count Puschkin, whence the two synonymous names Puschkinia and Adamsia; there is also another name, specific, which, though still used, has become discarded by authorities, viz., P. Libanotica—this was supposed to be in reference to one of its habitats being on Mount Lebanon. During mild winters it flowers in March, and so delicately marked are its blossoms that one must always feel that its beauties are mainly lost from the proverbial harshness of the season.

At the height of 4in. to 8in. the flowers are produced on slender bending scapes, the spikes of blossom are arranged one-sided; each flower is ½in. to nearly 1in. across, white, richly striped with pale blue down the centre, and on both sides of the petal-like divisions. The latter are of equal length, lance-shaped, and finely reflexed; there is a short tube, on the mouth of which is joined the smaller one of the corona. The latter is conspicuous from the reflexed condition of the limb of the perianth, and also from its lobes and membranous fringe being a soft lemon-yellow colour. The pedicels are slender and distant, causing the flower spikes, which are composed of four to eight flowers, to have a lax appearance. The leaves are few, 4in. to 6in. long, lance-shaped, concave, but flatter near the apex, of good substance and a dark green colour; bulb small.

As already stated, a little care is needed in planting this choice bulbous subject. It enjoys a rich, but light soil. It does not so much matter whether it is loamy or of a vegetable nature if it is light and well drained; and, provided it is planted under such conditions and in full sunshine, it will both bloom well and increase. It may be propagated by division of the roots during late summer, when the tops have died off; but only tufts having a crowded appearance should be disturbed for an increase of stock.

Flowering period, March to May.

P. s. compacta is a variety of the above, having a stronger habit and bolder flowers. The latter are more numerous, have shorter pedicels, and are compactly arranged in the spike—whence the name. Culture, propagation, and flowering time, same as last.

Pyrethrum Uliginosum

Marsh Feverfew; Nat. Ord. CompositæA very bold and strong growing species, belonging to a numerous genus; it comes to us from Hungary, and has been grown more or less in English gardens a little over sixty years. It is a distinct species, its large flowers, the height to which it grows, and the strength of its willow-like stalks being its chief characteristics. Still, to anyone with but a slight knowledge of hardy plants, it asserts itself at once as a Pyrethrum. It is hardy, herbaceous, and perennial, and worth growing in every garden where there is room for large growing subjects. There is something about this plant when in flower which a bare description fails to explain; to do it justice it should be seen when in full bloom.

Its flowers are large and ox-eye-daisy-like, having a white ray, with yellow centre, but the florets are larger in proportion to the disk; plain and quiet as the individual flowers appear, when seen in numbers (as they always may be seen on well-established specimens), they are strikingly beautiful, the blooms are more than 2in. across, and the mass comes level with the eye, for the stems are over 5ft. high, and though very stout, the branched stems which carry the flowers are slender and gracefully bending. The leaves are smooth, lance-shaped, and sharply toothed, fully 4in. long, and stalkless; they are irregularly but numerously disposed on the stout round stems, and of nearly uniform size and shape until the corymbose branches are reached, i.e., for 4ft. or 5ft. of their length; when the leaves are fully grown they reflex or hang down, and totally hide the stems. This habit, coupled with the graceful and nodding appearance of the large white flowers, renders this a pleasing subject, especially for situations where tall plants are required, such as near and in shrubberies. I grow but one strong specimen, and it looks well between two apple trees, but not over-shaded. The idea in planting it there was to obtain some protection from strong winds, and to avoid the labour and eyesore which staking would create.

It likes a stiff loam, but is not particular as to soil if only it is somewhat damp. The flowers last three weeks; and in a cut state are also very effective; and, whether so appropriated or left on the plant, they will be found to be very enduring. When cutting these flowers, the whole corymb should be taken, as in this particular case we could not wish for a finer arrangement, and being contemporaneous with the Michaelmas daisy, the bloom branches of the two subjects form elegant and fashionable decorations for table or vase use. To propagate this plant, it is only needed to divide the roots in November, and plant in deeply-dug but damp soil.

Flowering period, August to September.

Ramondia Pyrenaica

Syns. Chaixia Myconi and Verbascum Myconi; Nat. Ord. SolanaceæThis is a very dwarf and beautiful alpine plant, from the Pyrenees, the one and only species of the genus. Although it is sometimes called a Verbascum or Mullien, it is widely distinct from all the plants of that family. To lovers of dwarf subjects this must be one of the most desirable; small as it is, it is full of character.

The flowers, when held up to a good light, are seen to be downy and of ice-like transparency; they are of a delicate, pale, violet colour, and a little more than an inch in diameter, produced on stems 3in. to 4in. high, which are nearly red, and furnished with numerous hairs; otherwise the flower stems are nude, seldom more than two flowers, and oftener only one bloom is seen on a stem. The pedicels, which are about half-an-inch long, bend downwards, but the flowers, when fully expanded, rise a little; the calyx is green, downy, five-parted, the divisions being short and reflexed at their points; the corolla is rotate, flat, and, in the case of flowers several days old, thrown back; the petals are nearly round, slightly uneven, and waved at the edges, having minute protuberances at their base tipped with bright orange, shading to white; the seed organs are very prominent; stamens arrow-shaped; pistil more than twice the length of filaments and anthers combined, white, tipped with green. The leaves are arranged in very flat rosettes, the latter being from four to eight inches across. The foliage is entirely stemless, the nude flower stalks issuing from between the leaves, which are roundly toothed, evenly and deeply wrinkled, and elliptical in outline. Underneath, the ribs are very prominent, and the covering of hairs rather long, as are also those of the edges. On the upper surface the hairs are short and stiff.

In the more moist interstices of rockwork, where, against and between large stones, its roots will be safe from drought, it will not only be a pleasing ornament, but will be likely to thrive and flower well. It is perfectly hardy, but there is one condition of our climate which tries it very much—the wet, and alternate frosts and thaws of winter. From its hairy character and flat form, the plant is scarcely ever dry, and rot sets in. This is more especially the case with specimens planted flat; it is therefore a great help against such climatic conditions to place the plants in rockwork, so that the rosettes are as nearly as possible at right angles with the ground level. Another interesting way to grow this lovely and valuable species is in pans or large pots, but this system requires some shelter in winter, as the plants will be flat. The advantages of this mode are that five or six specimens so grown are very effective. They can, from higher cultivation (by giving them richer soil, liquid manure, and by judicious confinement of their roots), be brought into a more floriferous condition, and when the flowers appear, they can be removed into some cool light situation, under cover, so that their beauties can be more enjoyed, and not be liable to damage by splashing, &c. Plants so grown should be potted in sandy peat, and a few pieces of sandstone placed over the roots, slightly cropping out of the surface; these will not only help to keep the roots from being droughted, but also bear up the rosetted leaves, and so allow a better circulation of air about the collars, that being the place where rot usually sets in. In the case of specimens which do not get proper treatment, or which have undergone a transplanting to their disadvantage, they will often remain perfectly dormant to all appearance for a year or more. Such plants should be moved into a moist fissure in rockwork, east aspect, and the soil should be of a peaty character. This may seem like coddling, and a slur on hardy plants. Here, however, we have a valuable subject, which does not find a home in this climate exactly so happy as its native habitat, but which, with a little care, can have things so adapted to its requirements as to be grown year after year in its finest form; such care is not likely to be withheld by the true lover of choice alpines.

This somewhat slow-growing species may be propagated by division, but only perfectly healthy specimens should be selected for the purpose, early spring being the best time; by seed also it may be increased; the process, however, is slow, and the seedlings will be two years at least before they flower.

Flowering period, May to July.

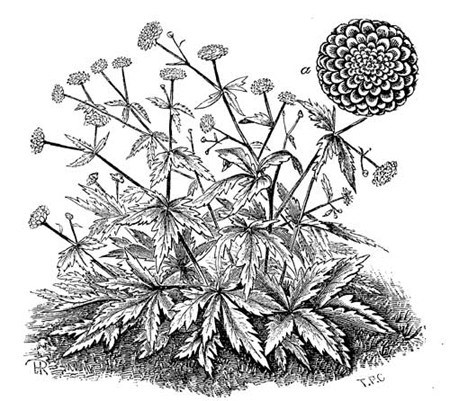

Ranunculus Aconitifolius

Aconite-leaved Crowfoot, or Bachelors' Buttons; Nat. Ord. RanunculaceæAn herbaceous perennial, of the alpine parts of Europe, and for a long time cultivated in this country. It grows 1ft. high, is much branched in zigzag form, and produces numerous flowers, resembling those of the strawberry, but only about half the size; the leaves are finely cut and of a dark green colour; it is not a plant worth growing for its flowers, but the reason why I briefly speak of it here is that I may more properly introduce that grand old flower of which it is the parent, R. a. fl.-pl. (see Fig. 79), the true "English double white Crowfoote," or Bachelor's Buttons; these are the common names which Gerarde gives as borne by this plant nearly 300 years ago, and there can be no mistaking the plant, as he figures it in his "Historie of Plantes," p. 812; true, he gives it a different Latin name to the one it bears at the present time; still, it is the same plant, and his name for it (R. albus multiflorus) is strictly and correctly specific. Numerous flowers are called Bachelor's Buttons, including daisies, globe flowers, pyrethrums, and different kinds of ranunculi, but here we have the "original and true;" probably it originated in some ancient English garden, as Gerarde says, "It groweth in the gardens of herbarists & louers of strange plants, whereof we have good plentie, but it groweth not wild anywhere."

Fig. 79. Ranunculus Aconit Folius Flore-pleno.

(One-fourth natural size; a, natural size of flower.)

Its round smooth stems are stout, zigzag, and much branched, forming the plant into a neat compact bush, in size (of plants two or more years old) 2ft. high and 2ft. through. The flowers are white, and very double or full of petals, evenly and beautifully arranged, salver shape, forming a flower sometimes nearly an inch across; the purity of their whiteness is not marred by even an eye, and they are abundantly produced and for a long time in succession. The leaves are of a dark shining green colour, richly cut—as the specific name implies—after the style of the Aconites; the roots are fasciculate, long, and fleshy.

This "old-fashioned" plant is now in great favour and much sought after; and no wonder, for its flowers are perfection, and the plant one of the most decorative and suitable for any position in the garden. In a cut state the flowers do excellent service. This subject is easily cultivated, but to have large specimens, with plenty of flowers, a deep, well enriched soil is indispensable; stagnant moisture should be avoided. Autumn is the best time to divide the roots.

Flowering period, May to July.

Ranunculus Acris Flore-pleno

Double Acrid Crowfoot, Yellow Bachelor's Buttons; Nat. Ord. RanunculaceæThe type of this is a common British plant, most nearly related to the field buttercup. I am not going to describe it, but mention it as I wish to introduce R. acris fl.-pl., sometimes called "yellow Bachelor's Buttons"—indeed, that is the correct common name for it, as used fully 300 years ago. In every way, with the exception of its fine double flowers, it resembles very much the tall meadow buttercup, so that it needs no further description; but, common as is its parentage, it is both a showy and useful border flower, and forms a capital companion to the double white Bachelor's Buttons (R. aconitifolius fl.-pl.).

Flowering period, April to June.

Ranunculus Amplexicaulis

Stem-clasping Ranunculus; Nat. Ord. RanunculaceæA very hardy subject; effective and beautiful. The form of this plant is exceedingly neat, and its attractiveness is further added to by its smooth and pale glaucous foliage. It was introduced into this country more than 200 years ago, from the Pyrenees. Still it is not generally grown, though at a first glance it asserts itself a plant of first-class merit (see Fig. 80).

The shortest and, perhaps, best description of its flowers will be given when I say they are white Buttercups, produced on stout stems nearly a foot high, which are also furnished by entire stem-clasping leaves, whence its name; other leaves are of varying forms, mostly broadly lance-shaped, and some once-notched; those of the root are nearly spoon-shaped. The whole plant is very smooth and glaucous, also covered with a fine meal. As a plant, it is effective; but grown by the side of R. montanus and the geums, which have flowers of similar shape, it is seen to more advantage.

On rockwork, in leaf soil, it does remarkably well; in loam it seems somewhat stunted. Its flowers are very serviceable in a cut state, and they are produced in succession for three or four weeks on the same plant. It has large, fleshy, semi-tuberous roots, and many of them; so that at any time it may be transplanted. I have pulled even flowering plants to pieces, and the different parts, which, of course, had plenty of roots to them, still continued to bloom.

Fig. 80. Ranunculus Amplexicaulis.

(One-fourth natural size.)

Flowering period, April and May.

Ranunculus Speciosum

Showy Crowfoot; Nat. Ord. RanunculaceæThis is another double yellow form of the Buttercup. It has only recently come into my possession. The blooms are very large and beautiful, double the size of R. acris fl.-pl., and a deeper yellow; the habit, too, is much more dwarf, the leaves larger, but similar in shape.

Flowering period, April to June.

All the foregoing Crowfoots are of the easiest culture, needing no particular treatment; but they like rich and deep soil. They may be increased by division at almost any time, the exceptions being when flowering or at a droughty season.

Rudbeckia Californica

Californian Cone-flower; Nat. Ord. CompositæThis, in all its parts, is a very large and showy subject; the flowers are 3in. to 6in. across, in the style of the sunflower. It has not long been grown in English gardens, and came, as its name implies, from California: it is very suitable for association with old-fashioned flowers, being nearly related to the genus Helianthus, or sunflower. It is not only perfectly hardy in this climate, which is more than can be said of very many of the Californian species, but it grows rampantly and flowers well. It is all the more valuable as a flower from the fact that it comes into bloom several weeks earlier than most of the large yellow Composites. Having stated already the size of its flower, I need scarcely add that it is one of the showiest subjects in the garden; it is, however, as well to keep it in the background, not only on account of its tallness, but also because of its coarse abundant foliage.

It grows 4ft. to 6ft. high, the stems being many-branched. The flowers have erect stout stalks, and vary in size from 3in. to 6in. across, being of a light but glistening yellow colour; the ray is somewhat unevenly formed, owing to the florets being of various sizes, sometimes slit at the points, lobed, notched, and bent; the disk is very bold, being nearly 2in. high, in the form of a cone, whence the name "cone flower." The fertile florets of the disk or cone are green, and produce an abundance of yellow pollen, but it is gradually developed, and forms a yellow ring round the dark green cone, which rises slowly to the top when the florets of the ray fall; from this it will be seen that the flowers last a long time. The leaves of the root are sometimes a foot in length and half as broad, being oval, pointed, and sometimes notched or lobed; also rough, from a covering of short stiff hairs, and having once-grooved stout stalks 9in. or more long; the leaves of the stems are much smaller, generally oval, but of very uneven form, bluntly pointed, distinctly toothed, and some of the teeth so large as to be more appropriately described as segments; the base abruptly narrows into a very short stalk. The flowers of this plant are sure to meet with much favour, especially while the present fashion continues; but apart from fashion, merely considered as a decorative subject for the garden, it is well worth a place. There are larger yellow Composites, but either they are much later, or they are not perennial species, and otherwise this one differs materially from them.