Полная версия

Полная версияBible Animals

In our Authorized Bible, there are one or two passages where the Hebrew word Kippôd is translated as Bittern. For example, there is Isaiah xiv. 22, 23, "I will cut off from Babylon the name, and remnant, and son and nephew, saith the Lord. I will also make it a possession for the bittern, and pools of water, and I will sweep it with the besom of destruction, saith the Lord of hosts."

Then there is another passage of the same prophet (xxxiv. 11), "But the cormorant and the bittern shall possess it (i.e. Idumea), the owl also and the raven shall dwell in it." The last mention of this creature occurs in Zephaniah ii. 14, "And flocks shall lie down in the midst of her (i.e. Nineveh), all the beasts of the nations: both the bittern and the cormorant shall lodge in the upper lintels of it; their voice shall sing in the windows; desolation shall be in the thresholds; for he shall uncover the cedar-work."

Now, in the "Jewish School and Family Bible," a new literal translation by Dr. A. Benisch, under the superintendence of the Chief Rabbi, the word Kippôd is translated, not as Bittern, but Hedgehog. As I shall have to refer to this translation repeatedly in the course of the present work, I will give a few remarks made by the translator in the preface.

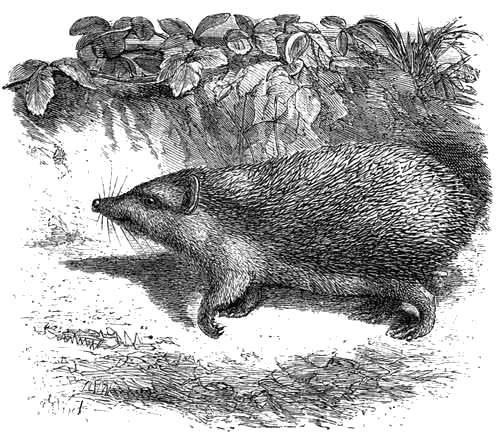

SYRIAN HEDGEHOG.

"Pelican and hedgehog shall possess it."—Isa. xxxiv. 11 (Jewish Bible).

After premising that both Christian and Jew agree in considering the Old Testament as emanating from God, and reverencing it as such, he proceeds to say that the former, as holding himself absolved from the ceremonial law of the Mosaic dispensation, has not the interest in the exact signification of every letter of the law which necessarily attaches itself to the Jew, who considers himself bound by that law, although some ceremonies, "by their special reference to the Temple in Jerusalem and the actual existence of Israel in the Holy Land, are at present not practicable."

He then observes that the translators of the authorized Anglican version, whose many excellences he fully admits, could not be considered as free agents, as they were bound by the positive injunctions of their monarch, as well as by the less obvious, but more powerful influence of Christian authorities, to alter the original translation as little as possible, and to keep the ecclesiastical words. Retaining, therefore, the renderings of the Anglican translation whenever it can be done without infringing upon absolute accuracy, the translator has marked with great care various passages where he has felt himself obliged to give a different rendering to the Hebrew. Whenever words, especially such as are evidently the names of animals, cannot be rendered with any amount of probability, they have not been translated at all, and to those about which there are good grounds of doubt a distinctive mark is affixed.

Now to the word Hedgehog, by which the Hebrew Kippôd is rendered, no such marking is attached in either of the three quoted passages, and it is evident therefore that the rendering is satisfactory to the highest authorities on the Hebrew language. And we have the greater assurance of this accuracy, because, in the mere translation of the name of an animal, no doctrinal point is involved, and so there can be no temptation to the translator to be carried away by preconceived ideas, and to give to the word that rendering which may tend to establish his peculiar doctrinal ideas.

The Septuagint also translates Kippôd as εχινος (echinus) i.e. the Hedgehog, and this rendering is advocated by the eminent scholar Gesenius, who considers it to be formed from the Hebrew word kaped, i.e. contracted; reference being of course made to the Hedgehog's habit of rolling itself up when alarmed, and presenting only an array of bristles to the enemy. This derivation of the word is certainly more convincing than a suggestion which has been made, that the Hebrew Kippôd may signify the Hedgehog, because it resembles the Arabic name of the same animal, viz. Kunfod.

As therefore the word Kippôd is translated as Hedgehog in the Septuagint and Jewish Bible, and as Bittern in the authorized version, we very naturally ask ourselves whether either or both of these animals inhabit Palestine and the neighbouring countries. We find that both are plentiful even at the present day, and that more than one species of Hedgehog and Bittern are known in the Holy Land. About the Bittern we shall treat in good time, and will now take up the rendering of Hedgehog.

There are at least two species of Hedgehog known in Palestine, that of the north being identical with our own well-known animal (Erinaceus Europœus), and the other being a distinct species (Erinaceus Syriacus). The latter animal is the species which has been chosen for illustration. It is smaller than its northern relative, lighter in colour, and, as may be seen from the illustration, is rather different in general aspect.

Its habits are identical with those of the European Hedgehog. Like that animal it is carnivorous, feeding on worms, snails, frogs, lizards, snakes, and similar creatures, and occasionally devouring the eggs and young of birds that make their nest on the ground.

Small as is the Hedgehog, it can devour all such animals with perfect ease, its jaws and teeth being much stronger than might be anticipated from the size of their owner.

One or two objections that have been made to the translation of the Kippôd as Hedgehog must be mentioned, so that the reader may see what is said on both sides in dubious cases. One objection is, that the Kippôd is (in Isaiah xiv. 23) mentioned in connexion with pools of water, and that, as the Hedgehog prefers dry places to wet, whereas the Bittern is essentially a marsh-dweller, the latter rendering of the word is preferable to the former. Again, as the Kippôd is said by Zephaniah to "lodge in the upper lintels," and its "voice to sing in the windows," it must be a bird, and not a quadruped. We will examine these passages separately, and see how they bear upon the subject. As to Zephaniah ii. 13, the Jewish Bible treats the passage as follows:—"And he will stretch out his hand against the north, and destroy Assyria; and will make Nineveh a desolation, and arid like the desert. And droves shall crouch in the midst of her, all the animals of nations: both pelican and hedgehog (Kippôd) shall lodge nightly in the knobs of it, a voice shall sing in the windows; drought shall be in the thresholds, for he shall uncover the cedar-work."

Now the reader will see that, so far from the notion of marsh-land being connected with the Kippôd, the whole imagery of the prophecy turns upon the opposite characteristics of desolation, aridity, and drought. The same imagery is used in Isaiah xxxiv. 7-12, which the Jewish Bible reads as follows, "For it is the day of the vengeance of the Eternal, and the year of recompenses for the quarrel of Zion. And the brooks thereof shall be turned into pitch, and the dust thereof into brimstone, and the land thereof shall become burning pitch. It shall not go out night nor day; the smoke of it shall go up for ever; from generation to generation it shall lie waste; none shall pass through it for ever and ever. Pelican and hedgehog (Kippôd) shall possess it; owls also and ravens shall dwell in it; and he shall stretch over it the line of desolation, and the stones of emptiness." And to the end of the chapter the same idea of drought, desolation, and solitude is carried out.

Thus, even putting the question in the simplest manner, we have two long passages which directly connect the Kippôd with drought, aridity, and desolation, in opposition to one in which the Kippôd and "pools of water" are mentioned in proximity to each other. Now the fact is, that the sites of Nineveh and Babylon fulfil both prophecies, being both dry and marshy—dry away from the river, and marshy among the reed-swamps that now exist on its banks.

So much for the question of locality.

As to the second objection, namely, that the Kippôd was to lodge in the upper lintels, and therefore must be a bird, and not a quadruped, it is sufficient to say that the allusion is evidently made to ruins that are thrown down, and not to buildings that are standing upright.

As to the words, "their voices shall sing in the windows," the reader may see, on reference to the English Bible, that the word "their" is printed in italics, showing that it does not exist in the original, and has been supplied by the translator. Taking the passage as it really stands, "Both the cormorant and the bittern (Kippôd) shall lodge in the upper lintels of it; a voice shall sing in the windows," it is evident that the voice or sound which sings in the windows does not necessarily refer to the cormorant and Bittern at all. Dr. Harris remarks that "the phrase is elliptical, and implies 'the voice of birds.'"

THE PORCUPINE

Presumed identity of the Kippôd with the Porcupine—The same Greek name applied to the Porcupine and Hedgehog—Habits of the Porcupine—the common Porcupine found plentifully in Palestine.

Although, like the hedgehog, the Porcupine is not mentioned by name in the Scriptures, many commentators think that the word Kippôd signifies both the hedgehog and Porcupine.

That the two animals should be thought to be merely two varieties of one species is not astonishing, when we remember the character of the people among whom the Porcupine lives. Not having the least idea of scientific geology, they look only to the most conspicuous characteristics, and because the Porcupine and hedgehog are both covered with an armature of quills, and the quills are far more conspicuous than the teeth, the inhabitants of Palestine naturally class the two animals together. In reality, they belong to two very different orders, the hedgehog being classed with the shrew-mice and moles, while the Porcupine is a rodent animal, and is classed with the rats, rabbits, beavers, marmots, and other rodents.

At the present day the inhabitants of the Holy Land believe the Porcupine to be only a large species of hedgehog, and the same name is applied to both animals. Such is the case even in the Greek language, the word Hystrix (ὕστριγξ or ὕσθριξ) being employed indifferently in either sense.

Its food is different from that of the hedgehog, for whereas the hedgehog lives entirely on animal food, as has been already mentioned, the Porcupine is as exclusively a vegetable eater, feeding chiefly on roots and bark.

It is quite as common in Palestine as the hedgehog, a fact which increases the probability that the two animals may have been mentioned under a common title. Being a nocturnal animal, it retires during the day-time to some crevice in a rock or burrow in the ground, and there lies sleeping until the sunset awakens it and calls it to action. And as the hedgehog is also a nocturnal animal, the similarity of habit serves to strengthen the mutual resemblance.

The Porcupine is peculiarly fitted for living in dry and unwatered spots, as, like many other animals, of which our common rabbit is a familiar example, it can exist without water, obtaining the needful moisture from the succulent roots on which it feeds.

The sharply pointed quills with which its body is covered are solid, and strengthened in a most beautiful manner by internal ribs, that run longitudinally along its length, exactly like those of the hollow iron masts, which are now coming so much into use. As they are, in fact, greatly developed hairs, they are continually shed and replaced, and when they are about to fall are so loosely attached that they fall off if pulled slightly, or even if the animal shakes itself. Consequently the shed quills that lie about the localities inhabited by the Porcupine indicate its whereabouts, and so plentiful are these quills in some places that quite a bundle can be collected in a short time.

There are many species of Porcupines which inhabit different parts of the world, but that which has been mentioned is the common Porcupine of Europe, Asia, and Africa (Hystrix cristata).

THE MOLE

The two Hebrew words which are translated as Mole—Obscurity of the former name—A parallel case in our own language—The second name—The Moles and the Bats, why associated together—The real Mole of Scripture, its different names, and its place in zoology—Description of the Mole-rat and its general habits—Curious superstition—Discovery of the species by Mr. Tristram—Scripture and science—How the Mole-rat finds its food—Distinction between the Mole and the present animal.

There are two words which are translated as Mole in our authorized version of the Bible. One of them is so obscure that there seems no possibility of deciding the creature that is represented by it. We cannot even tell to what class of the animal kingdom it refers, because in more than one place it is mentioned as one of the unclean birds that might not be eaten (translated as swan in our version), whereas, in another place, it is enumerated among the unclean creeping things.

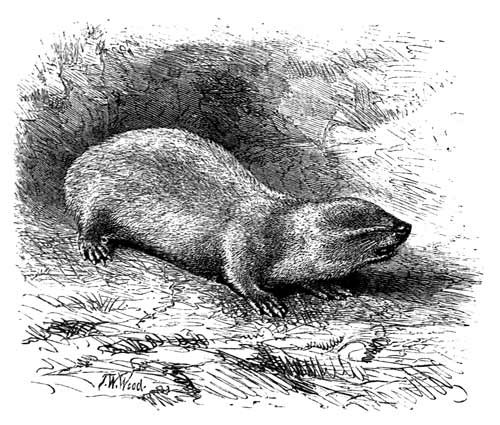

THE MOLE-RAT.

"These also shall be unclean unto you among the creeping things that creep upon the earth … the lizard, the snail, and the mole."—Lev. xi. 29, 30.

We may conjecture that the same word might be used to designate two distinct animals, though we have no clue to their identification. It is rather a strange coincidence, in corroboration of this theory, that our word Mole signifies three distinct objects—firstly, an animal; secondly, a cutaneous growth; and thirdly, a bank of earth. Now, supposing English to be a dead language, like the Hebrew, it may well be imagined that a translator of an English book would feel extremely perplexed when he saw the word Mole used in such widely different senses.

The best Hebraists can do no more than offer a conjecture founded on the structure of the word Tinshemeth, which is thought by some to be the chameleon. Some think that it is the Mole, some the ibis, some the salamander, while others consider it to be the centipede; and in neither case have any decisive arguments been adduced.

We will therefore leave the former of these two names, and proceed to the second, Chephor-peroth.

This word occurs in that passage of Isaiah which has already been quoted when treating of the bat. "In that day a man shall cast his idols of silver and his idols of gold, which they made each one to himself to worship, to the moles and to the bats; to go into the clefts of the rocks and into the tops of the ragged rocks, for fear of the Lord and for the glory of his majesty, when he ariseth to shake terribly the earth."

It is highly probable that the animal in question is the Mole of Palestine, which is not the same as our European species, but is much larger in size, and belongs to a different order of mammalia. The true Mole is one of the insectivorous and carnivorous animals, and is allied to the shrews and the hedgehogs; whereas the Mole of Palestine (Spalax typhlus) is one of the rodents, and allied to the rabbits, mice, marmots, and jerboas. A better term for it is the Mole-rat, by which name it is familiar to zoologists. It is also known by the names of Slepez and Nenni.

In length it is about eight inches, and its colour is a pale slate. As is the case with the true Moles, the eyes are of very minute dimensions, and are not visible through the thick soft fur with which the whole head and body are covered. Neither are there any visible external ears, although the ear is really very large, and extremely sensitive to sound. This apparent privation of both ears and eyes gives to the animal a most singular and featureless appearance, its head being hardly recognisable as such but for the mouth, and the enormous projecting teeth, which not only look formidable, but really are so. There is a curious superstition in the Ukraine, that if a man will dare to grasp a Mole-rat in his bare hand, allow it to bite him, and then squeeze it to death, the hand that did the deed will ever afterwards possess the virtue of healing goitre or scrofula.

This animal is spread over a very large tract of country, and is very common in Palestine. Mr. Tristram gives an interesting account of its discovery. "We had long tried in vain to capture the Mole of Palestine. Its mines and its mounds we had seen everywhere, and reproached ourselves with having omitted the mole-trap among the items of our outfit. From the size of the mounds and the shallowness of the subterranean passages, we felt satisfied it could not be the European species, and our hopes of solving the question were raised when we found that one of them had taken up its quarters close to our camp. After several vain attempts to trap it, an Arab one night brought a live Mole in a jar to the tent. It was no Mole properly so called, but the Mole-rat, which takes its place throughout Western Asia. The man, having observed our anxiety to possess a specimen, refused to part with it for less than a hundred piastres, and scornfully rejected the twenty piastres I offered. Ultimately, Dr. Chaplin purchased it for five piastres after our departure, and I kept it alive for some time in a box, feeding it on sliced onions."

The same gentleman afterwards caught many of the Mole-rats, and kept them in earthen vessels, as they soon gnawed their way through wood. They fed chiefly on bulbs, but also ate sopped bread. Like many other animals, they reposed during the day, and were active throughout the night.

The author then proceeds to remark on the peculiarly appropriate character of the prophecy that the idols should be cast to the Moles and the bats. Had the European Mole been the animal to which reference was made, there would have been comparatively little significance in the connexion of the two names, because, although both animals are lovers of darkness, they do not inhabit similar localities. But the Mole-rat is fond of frequenting deserted ruins and burial-places, so that the Moles and the bats are really companions, and as such are associated together in the sacred narrative. Here, as in many other instances, we find that closer study of the Scriptures united to more extended knowledge are by no means the enemies of religion, as some well-meaning, but narrow-minded persons think. On the contrary, the Scriptures were never so well understood, and their truth and force so well recognised, as at the present day; and science has proved to be, not the destroyer of the Bible, but its interpreter. We shall soon cease to hear of "Science versus the Bible," and shall substitute "Science and the Bible versus Ignorance and Prejudice."

The Mole-rat needs not to dig such deep tunnels as the true Moles, because its food does not lie so deep. The Moles live chiefly upon earthworms, and are obliged to procure them in the varying depths to which they burrow. But the Mole-rat lives mostly upon roots, preferring those of a bulbous nature. Now bulbous roots are, as a rule, situated near the surface of the ground, and, therefore, any animal which feeds upon them must be careful not to burrow too deeply, lest it should pass beneath them. The shallowness of the burrows is thus accounted for. Gardens are often damaged by this animal, the root-crops, such as carrots and onions, affording plenty of food without needing much exertion.

The Mole-rat does not keep itself quite so jealously secluded as does our common Mole, but occasionally will come out of the burrow and lie on the ground, enjoying the warm sunshine. Still it is not easily to be approached; for though its eyes are almost useless, the ears are so sharp, and the animal is so wary, that at the sound of a footstep it instantly seeks the protection of its burrow, where it may bid defiance to its foes.

How it obtains its food is a mystery. There seems to be absolutely no method of guiding itself to the precise spot where a bulb may be growing. It is not difficult to conjecture the method by which the Mole discovers its prey. Its sensitive ears may direct it to the spot where a worm is driving its way through the earth, and should it come upon its prey, the very touch of the worm, writhing in terror at the approach of its enemy, would be sufficient to act as a guide. I have kept several Moles, and always noticed that, though they would pass close to a worm without seeming to detect its presence, either by sight or scent, at the slightest touch they would spring round, dart on the worm, and in a moment seize it between their jaws. But with the Mole-rat the case is different. The root can utter no sound, and can make no movement, nor is it likely that the odour of the bulb should penetrate through the earth to a very great distance.

THE MOUSE

Conjectures as to the right translation of the Hebrew word Akbar—Signification of the word—The Mice which marred the land—Miracles, and their economy of power—The Field-mouse—Its destructive habits and prolific nature—The insidious nature of its attacks, and its power of escaping observation—The Hamster, and its habits—Its custom of storing up provisions for the winter—Its fertility and unsociable nature—The Jerboa, its activity and destructiveness—Jerboas and Hamsters eaten by Arabs and Syrians—Various species of Dormice and Sand-rats.

That the Mouse mentioned in the Old Testament was some species of rodent animal is tolerably clear, though it is impossible to state any particular species as being signified by the Hebrew word Akbar. The probable derivation of this name is from two words which signify "destruction of corn," and it is therefore evident that allusion is made to some animal which devours the produce of the fields, and which exists in sufficient numbers to make its voracity formidable.

Some commentators on the Old Testament translate the word Akbar as jerboa. Now, although the jerboa is common in Syria, it is not nearly so plentiful as other rodent animals, and would scarcely be selected as the means by which a terrible disaster is made to befall a whole country. The student of Scripture is well aware that, in those exceptional occurrences which are called miracles, a needless development of the wonder-working power is never employed. We are not to suppose, for example, that the clouds of locusts that devoured the harvests of the Egyptians were created for this express purpose, but that their already existing hosts were concentrated upon a limited area, instead of being spread over a large surface. Nor need we fancy that the frogs which rendered their habitations unclean, and contaminated their food, were brought into existence simply to inflict a severe punishment on the fastidious and superstitious Egyptians.

Of course, had such an exercise of creative power been needed, it would have been used, but we can all see that a needless miracle is never worked. He who would not suffer even a crumb of the miraculously multiplied bread to be wasted, is not likely to waste that power by which the miracle was wrought.

If we refer to the early history of the Israelitish nation, as told in 1 Sam. iv.—vi., we shall find that the Israelites made an unwarrantable use of the ark, by taking it into battle, and that it was captured and carried off into the country of the Philistines. Then various signs were sent to warn the captors to send the ark back to its rightful possessors. Dagon, the great fish-god, was prostrated before it, painful diseases attacked them, so that many died, and scarcely any seem to have escaped, while their harvests were ravaged by numbers of "mice that marred the land."

The question is now simple enough. If the ordinary translation is accepted, and the word Akbar rendered as Mouse, would the necessary conditions be fulfilled, i.e. would the creature be destructive, and would it exist in very great numbers? Now we shall find that both these conditions are fulfilled by the common Field-mouse (Arvicola arvalis).

This little creature is, in proportion to its size, one of the most destructive animals in the world. Let its numbers be increased from any cause whatever, and it will most effectually "mar the land." It will devour every cereal that is sown, and kill almost any sapling that is planted. It does not even wait for the corn to spring up, but will burrow beneath the surface, and dig out the seed before it has had time to sprout. In the early part of the year, it will eat the green blade as soon as it springs out of the ground, and is an adept at climbing the stalks of corn, and plundering the ripe ears in the autumn.