Полная версия

Полная версияBible Animals

The front pair of wings, which alone were seen before they were expanded, became comparatively insignificant, while the hinder pair, which were before invisible, became the most prominent part of the insect, their translucent folds being coloured with the most brilliant hues, according to the species. The body seems to have shrunk as the wings have increased, and to have diminished to half its previous size, while the long legs that previously were so conspicuous are stretched out like the legs of a flying heron.

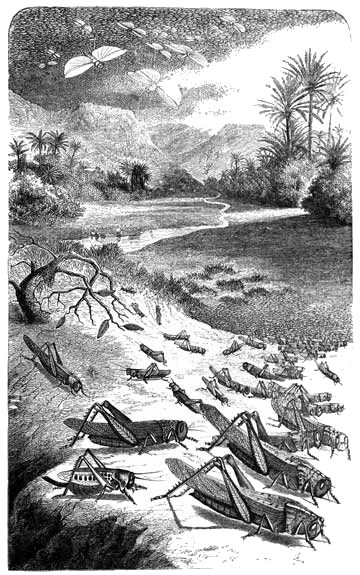

All the Locusts are vegetable-feeders, and do great harm wherever they happen to be plentiful, their powerful jaws severing even the thick grass stems as if cut by scissors. But it is only when they invade a country that their real power is felt. They come flying with the wind in such vast multitudes that the sky is darkened as if by thunder-clouds; and when they settle, every vestige of green disappears off the face of the earth.

Mr. Gordon Cumming once saw a flight of these Locusts. They flew about three hundred feet from the ground, and came on in thick, solid masses, forming one unbroken cloud. On all sides nothing was to be seen but Locusts. The air was full of them, and the plain was covered with them, and for more than an hour the insect army flew past him. When the Locusts settle, they eat with such voracity that the sound caused by their jaws cutting the leaves and grass can be heard at a great distance; and even the young Locusts, which have no wings, and are graphically termed by the Dutch colonists of Southern Africa "voet-gangers," or foot-goers, are little inferior in power of jaw to the fully-developed insect.

As long as they have a favourable wind, nothing stops the progress of the Locusts. They press forward just like the vast herds of antelopes that cover the plains of Africa, or the bisons that blacken the prairies of America, and the progress of even the wingless young is as irresistible as that of the adult insects. Regiments of soldiers have in vain attempted to stop them. Trenches have been dug across their path, only to be filled up in a few minutes with the advancing hosts, over whose bodies the millions of survivors continued their march. When the trenches were filled with water, the result was the same; and even when fire was substituted for water, the flames were quenched by the masses of Locusts that fell into them. When they come to a tree, they climb up it in swarms, and devour every particle of foliage, not even sparing the bark of the smaller branches. They ascend the walls of houses that come in the line of their march, swarming in at the windows, and gnawing in their hunger the very woodwork of the furniture.

THE LOCUST.

"All thy trees shall the locust consume."—Deut. xxviii. 42.

We shall now see how true to nature is the terrible prophecy of Joel. "A day of darkness and of gloominess, a day of clouds and of thick darkness, as the morning spread upon the mountains: a great people and a strong; there hath not been ever the like, neither shall be any more after it, even to the years of many generations.

"A fire devoureth before them; and behind them a flame burneth: the land is as the garden of Eden before them, and behind them a desolate wilderness; yea, and nothing shall escape them.

"The appearance of them is as the appearance of horses; and as horsemen, so shall they run.

"Like the noise of chariots on the tops of mountains shall they leap, like the noise of a flame of fire that devoureth the stubble, as a strong people set in battle array....

"They shall run like mighty men; they shall climb the wall like men of war; and they shall march every one on his ways, and they shall not break their ranks:

"Neither shall one thrust another; they shall walk every one in his path: and when they fall upon the sword, they shall not be wounded.

"They shall run to and fro in the city; they shall run upon the wall, they shall climb up upon the houses; they shall enter in at the windows like a thief.

"The earth shall quake before them; the heavens shall tremble: the sun and the moon shall be dark, and the stars shall withdraw their shining:

"And the Lord shall utter His voice before His army: for His camp is very great".(Joel ii. 2-11).

Nothing can be more vividly accurate than this splendid description of the Locust armies. First we have the darkness caused by them as they fly like black clouds between the sun and the earth. Then comes the contrast between the blooming and fertile aspect of the land before they settle on it, and its utter desolation when they leave it. Then the poet-prophet alludes to the rushing noise of their flight, which he compares to the sound of chariots upon the mountains, and to the compact masses in which they pass over the ground like soldiers on the march. The impossibility of checking them is shown in verse 8, and their climbing the walls of houses and entering the chambers in verse 9.

There is one passage in the Scriptures which at first sight seems rather obscure, but is clear enough when we understand the character of the insect to which it refers: "I am gone like the shadow when it declineth: I am tossed up and down as the locust" (Ps. cix. 23).

Although the Locusts have sufficient strength of flight to remain on the wing for a considerable period, and to pass over great distances, they have little or no command over the direction of their flight, and always travel with the wind, just as has been mentioned regarding the quail. So entirely are they at the mercy of the wind, that if a sudden gust arises the Locusts are tossed about in the most helpless manner; and if they should happen to come across one of the circular air-currents that are so frequently found in the countries which they inhabit, they are whirled round and round without the least power of extricating themselves.

The course then of the Locust-swarms depends entirely on the direction of the wind. They are brought by the wind, and they are taken away by the wind, as is mentioned in the sacred narrative. In the account of the great plague of Locusts, the wind is mentioned as the proximate cause both of their arrival and their departure. See, for example, Exod. x. 12, 13:

"And the Lord said unto Moses, Stretch out thine hand over the land of Egypt for the locusts, that they may come up upon the land of Egypt, and eat every herb of the land, even all that the hail hath left.

"And Moses stretched forth his rod over the land of Egypt, and the Lord brought an east wind upon the land all that day, and all that night; and when it was morning, the east wind brought the locusts."

Afterwards, when Moses was brought before Pharaoh, and entreated to remove the plague which had been brought upon the land, the west wind was employed to take the Locusts away, just as the east wind had brought them.

"He went out from Pharaoh, and entreated the Lord.

"And the Lord turned a mighty strong west wind, which took away the locusts, and cast them into the Red Sea; there remained not one locust in all the coasts of Egypt" (Exod. x. 18, 19).

Modern travellers have given accounts of these Locust armies, which exactly correspond with the sacred narrative. One traveller mentions that, after a severe storm, the Locusts were destroyed in such multitudes, that they were heaped in a sort of wall, varying from three to four feet in height, fifty miles in length, and almost unapproachable, on account of the odour of their decomposing bodies.

We now come to the use of Locusts as food.

Very few insects have been recognised as fit for human food, even among uncivilized nations, and it is rather singular that the Israelites, whose dietary was so scrupulously limited, should have been permitted the use of the Locust. These insects are, however, eaten in all parts of the world which they frequent, and in some places form an important article of diet, thus compensating in some way for the amount of vegetable food which they consume.

Herodotus, for example, when describing the various tribes of Libyans, mentions the use of the Locust as an article of diet. "The Nasamones, a very numerous people, adjoin these Auschisæ westward.... When they have caught locusts, they dry them in the sun, reduce them to powder, and, sprinkling them in milk, drink them." (Melpomene, ch. 172.)

This is precisely the plan which is followed at the present day by the Bosjesmans of Southern Africa.

To them the Locusts are a blessing, and not a plague. They till no ground, so that they care nothing for crops, and they breed no cattle, so that they are indifferent about pasture land.

When they see a cloud of Locusts in the distance they light great fires, and heap plenty of green boughs upon them, so as to create a thick smoke. The Locusts have no idea of avoiding these smoke columns, but fly over the fires, and, stifled by the vapour, fall to the ground, where they are caught in vast numbers by the Bosjesmans.

When their captors have roasted and eaten as many as they can manage to devour, they dry the rest over the fires, pulverize them between two stones, and keep the meal for future use, mixing it with water, or, if they can get it, with milk.

We will now take a few accounts given by travellers of the present day, selecting one or two from many. Mr. W. G. Palgrave, in his "Central and Eastern Arabia," gives a description of the custom of eating Locusts. "On a sloping bank, at a short distance in front, we discerned certain large black patches, in strong contrast with the white glisten of the soil around, and at the same time our attention was attracted by a strange whizzing, like that of a flight of hornets, close along the ground, while our dromedaries capered and started as though struck with sudden insanity.

"The cause of all this was a vast swarm of locusts, here alighted in their northerly wanderings from their birthplace in the Dahna; their camp extended far and wide, and we had already disturbed their outposts. These insects are wont to settle on the ground after sunset, and there, half-stupified by the night chill, await the morning rays, which warm them once more into life and movement.

"This time, the dromedaries did the work of the sun, and it would be hard to say which of the two were the most frightened, they or the locusts. It was truly laughable to see so huge a beast lose his wits for fear at the flight of a harmless, stingless Insect, for, of all timid creatures, none equal this 'ship of the desert' for cowardice.

"But, if the beasts were frightened, not so their masters. I really thought they would have gone mad for joy. Locusts are here an article of food, nay, a dainty, and a good swarm of them is begged of Heaven in Arabia....

"The locust, when boiled or fried, is said to be delicious, and boiled and fried accordingly they are to an incredible extent. However, I never could persuade myself to taste them, whatever invitations the inhabitants of the land, smacking their lips over large dishes full of entomological 'delicatesses,' would make me to join them. Barakàt ventured on one for a trial. He pronounced it oily and disgusting, nor added a second to the first: it is caviare to unaccustomed palates.

"The swarm now before us was a thorough godsend for our Arabs, on no account to be neglected. Thirst, weariness, all were forgotten, and down the riders leaped from their starting camels. This one spread out a cloak, that one a saddle-bag, a third his shirt, over the unlucky creatures, destined for the morning meal. Some flew away, whizzing across our feet; others were caught, and tied up in sacks."

Mr. Mansfield Parkyns, in his "Life in Abyssinia," mentions that the true Abyssinian will not eat the Locust, but that the negroes and Arabs do so. He describes the flavour as being something between the burnt end of a quill and a crumb of linseed cake. The flavour, however, depends much on the mode of cooking, and, as some say, on the nature of the Locusts' food.

Signor Pierotti states, in his "Customs and Traditions of Palestine," that Locusts are really excellent food, and that he was accustomed to eat them, not from necessity, but from choice, and compares their flavour to that of shrimps.

Dr. Livingstone makes a similar comparison. In Palestine, Locusts are eaten either roasted or boiled in salt and water, but, when preserved for future use, they are dried in the sun, their heads, wings, and legs picked off, and their bodies ground into dust. This dust has naturally a rather bitter flavour, which is corrected by mixing it with camel's milk or honey, the latter being the favourite substance.

We may now see that the food of St. John the Baptist was, like his dress, that of a people who lived at a distance from towns, and that there was no more hardship in the one than in the other. Some commentators have tried to prove that St. John fed on the fruit of the locust or carob tree—the same that is used so much in this country for feeding cattle; but there is not the least ground for such an explanation. The account of his life, indeed, requires no explanation; Locust-dust, mixed with honey, being an ordinary article of food even at the present day.

HYMENOPTERA.

THE BEE

The Hebrew word Debôrah—The Honey Bee of Palestine—Abundance of Bees in the Holy Land—Habitations of the wild Bee—Hissing for the Bee—Bees in dead carcases—The honey of Scripture—Domesticated Bees and their hives—Stores of wild honey—The story of Jonathan—The Crusaders and the honey—Butter and honey—Oriental sweetmeats—The Dibs, or grape-honey, and mode of preparation—Wax, its use as a metaphor.

Passing for the moment the order of insects called Neuroptera, which may possibly be represented in the Scriptural writings by the Termites, which would be classed with the ants, we come to the vast order of Hymenoptera, of which we find several representatives. Beginning with that which is most familiar to us, we will take the Bee, an insect which is frequently mentioned in the Scriptures, and to which indirect allusion is made in many passages, such as those which mention honey, honeycomb, and wax.

Fortunately, there is no doubt about the rendering of the Hebrew word debôrah, which has always been acknowledged to be rightly translated as "Bee." There has, however, been a difference of opinion as to the derivation of the word, some Hebraists thinking that it is derived from a word which signifies departure, or going forth, in allusion to its habit of swarming, while others derive it from the Hebrew dabar, a word which signifies speech, and is appropriate to the Bee on account of the varied sounds of its hum, which were supposed to be the language of the insect.

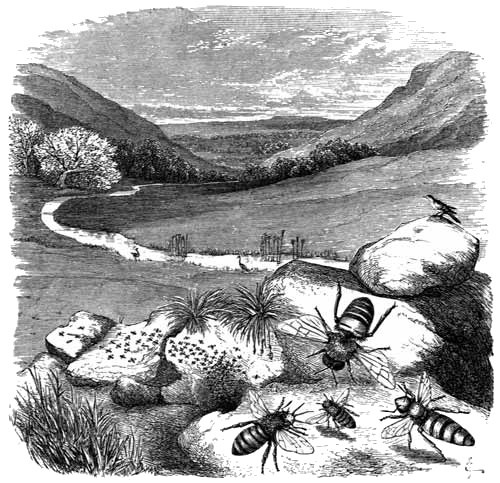

The Honey Bee is exceedingly plentiful in Palestine, and in some parts of the country multiplying to such an extent that the precipitous ravines in which it takes up its residence are almost impassable by human beings, so jealous are the Bees of their domains. Although the Bee is not exactly the same species as that of our own country, being the Banded Bee (Apis fasciata), and not the Apis mellifica, the two insects very much resemble each other in shape, colour, and habits. Both of them share the instinctive dislike of strangers and jealousy of intrusion, and the Banded Bee of Palestine has as great an objection to intrusion as its congener of England.

THE BEE.

"They shall rest all of them in the desolate valleys and in the holes of the rocks."—Isa. vii. 19.

Several allusions are made in the Scriptures to this trait in the character of the Bee. See, for example, Deut. i. 44: "And the Amorites, which dwelt in that mountain, came out against you, and chased you, as bees do, and destroyed you in Seir, even unto Hormah." All those who have had the misfortune to offend Bees will recognise the truth of this metaphor, the Amorites swarming out of the mountain like wild Bees out of the rocky clefts which serve them as hives, and chasing the intruder fairly out of their domains.

A similar metaphor is employed in the Psalms: "They compassed me about; yea, they compassed me about; but in the name of the Lord I will destroy them.

"They compassed me about like bees, they are quick as the fire of thorns, but in the name of the Lord I will destroy them."

There is another passage in which the Bee is mentioned in the light of an enemy: "And it shall come to pass in that day, that the Lord shall hiss for the fly that is in the uttermost part of the rivers of Egypt, and for the bee that is in the land of Assyria.

"And they shall come, and shall rest all of them in the desolate valleys, and in the holes of the rocks, and upon all thorns, and upon all bushes" (Isa. vii. 18, 19). Some commentators have thought that the word which is translated as "Bee" may in this case refer to some noxious fly, which, although it is not a Bee, and does not even belong to the same order of insects, has a sufficiently Bee-like appearance to cause it to be classed among the Bees by the non-zoological Orientals. The context, however, sets the question at rest; for the allusions to the resting of the insect in the holes of the rock, upon the thorns, and on the bushes, clearly refers to the mode in which the Honey Bee throws off its swarms.

The custom of swarming is mentioned in one of the earlier books of Scripture. The reader will remember that, after Samson had killed the lion which met him on the way, he left the carcase alone. The various carnivorous beasts and birds at once discover such a banquet, and in a very short time the body of a dead animal is reduced to a hollow skeleton, partially or entirely covered with skin, the rays of the sun drying and hardening the skin until it is like horn.

In exceptionally hot weather, the same result occurs even in this country. Some years before this account was written there was a very hot and dry summer, and a great mortality took place among the sheep. So many indeed died that at last their owners merely flayed them, and left their bodies to perish. One of the dead sheep had been thrown into a rather thick copse, and had fallen in a spot where it was sheltered from the wind, and yet exposed to the fierce heat of the summer's sun. The consequence was that in a few days it was reduced to a mere shell. The heat hardened and dried the external layer of flesh so that not even the carnivorous beetles could penetrate it, while the whole of the interior dissolved into a semi-putrescent state, and was rapidly devoured by myriads of blue-bottles and other larvæ.

It was so thoroughly dried that scarcely any evil odour clung to it, and as soon as I came across it the story of Samson received a simple elucidation. In the hotter Eastern lands, the whole process would have been more rapid and more complete, and the skeleton of the lion, with the hard and horny skin strained over it, would afford exactly the habitation of which a wandering swarm of Bees would take advantage. At the present day swarms of wild Bees often make their habitations within the desiccated bodies of dead camels that have perished on the way.

As to the expression "hissing" for the Bee, the reader must bear in mind that a sharp, short hiss is the ordinary call in Palestine, when one person desires to attract the attention of another. A similar sound, which may perhaps be expressed by the letters tst, prevails on the Continent at the present day. Signor Pierotti remarks that the inhabitants of Palestine are even now accustomed to summon Bees by a sort of hissing sound.

Whether the honey spoken of in the Scriptures was obtained from wild or domesticated Bees is not very certain, but, as the manners of the East are much the same now as they were three thousand years ago, it is probable that Bees were kept then as they are now. The hives are not in the least like ours, but are cylindrical vases of coarse earthenware, laid horizontally, much like the bark hives employed in many parts of Southern Africa.

In some places the hives are actually built into the walls of the houses, the closed end of the cylinder projecting into the interior, while an entrance is made for the Bees in the other end, so that the insects have no business in the house. When the inhabitants wish to take the honey, they resort to the operation which is technically termed "driving" by bee-masters.

They gently tap the end within the house, and continue the tapping until the Bees, annoyed by the sound, have left the hive. They then take out the circular door that closes the end of the hive, remove as much comb as they want, carefully put back those portions which contain grubs and bee-bread, and replace the door, when the Bees soon return and fill up the gaps in the combs. As to the wasteful, cruel, and foolish custom of "burning" the Bees, the Orientals never think of practising it.

In many places the culture of Bees is carried out to a very great extent, numbers of the earthenware cylinders being piled on one another, and a quantity of mud thrown over them in order to defend them from the rays of the sun, which would soon melt the wax of the combs.

In consequence of the geographical characteristics of the Holy Land, which supplies not only convenient receptacles for the Bees in the rocks, but abundance of thyme and similar plants, vast stores of bee-comb are to be found in the cliffs, and form no small part of the wealth of the people.

Reference to this kind of property is made by the Prophet Jeremiah. When Ishmael, the son of Nethaniah, had treacherously killed Gedaliah and others, ten men tried to propitiate him by a bribe: "Slay us not, for we have treasures in the field, of wheat, of barley, and of oil, and of honey" (chap. xli. 8). References to the wild honey are frequent in the Scriptures. For example, in the magnificent song of Moses the Lord is said to have made Israel to "suck honey out of the rock" (Deut. xxxii. 13). See also Psalm lxxxi. 16: "He should have fed them also with the finest of the wheat: and with honey out of the rock should I have satisfied thee."

The abundance of wild honey is shown by the memorable events recorded in 1 Sam. xiv. Saul had prohibited all the people from eating until the evening. Jonathan, who had not heard the prohibition, was faint and weary, and, seeing honey dripping on the ground from the abundance and weight of the comb, he took it up on the end of his staff, and ate sufficient to restore his strength.

Thus, if we refer again to the history of St. John the Baptist and his food, we shall find that he was in no danger of starving for want of nourishment, the Bees breeding abundantly in the desert places he frequented, and affording him a plentiful supply of the very material which was needed to correct the deficiencies of the dried locusts which he used instead of bread.

The expression "a land flowing with milk and honey" has become proverbial as a metaphor expressive of plenty. Those to whom the words were spoken understood it as something more than a metaphor. In the work to which reference has already been made Signor Pierotti writes as follows:—"Let us now see how far the land could be said to flow with milk and honey during the latter part of its history and at the present day.

"We find that honey was abundant in the time of the Crusades, for the English, who followed Edward I. to Palestine, died in great numbers from the excessive heat, and from eating too much fruit and honey. (See M. Sanutus, 'Liber secretorum fidelium Crucis,' lib. iii. p. xii.)

"At the present day, after traversing the country in every direction, I am able to affirm that in the south-east and north-east, where the ancient customs of the patriarchs are most fully preserved, and the effects of civilization have been felt least, milk and honey may still be said to flow, as they form a portion of every meal, and may even be more abundant than water, which fails occasionally in the heat of summer.... I have often eaten of the comb, which I found very good and of delicious fragrance."

A reference to sickness occasioned by eating too much honey occurs in Prov. xxv. 16: "Hast thou found honey? Eat so much as is sufficient for thee, lest thou be filled therewith, and vomit it." A similar warning is given in verse 27: "It is not good to eat much honey: so for men to search their own glory is not glory."