Полная версия

Полная версияGossip in the First Decade of Victoria's Reign

“The Duke of Wellington, in the interview to which your Majesty subsequently admitted him, understood, also, that this was your Majesty’s determination, and concurred with Sir Robert Peel in opinion that, considering the great difficulties of the present crisis, and the expediency of making every effort, in the first instance, to conduct the public business of the country with the aid of the present Parliament, it was essential to the success of the commission with which your Majesty had honoured Sir Robert Peel, that he should have that public proof of your Majesty’s entire support and confidence, which would be afforded by the permission to make some changes in that part of your Majesty’s household, which your Majesty resolved on maintaining entirely without change.

“Having had the opportunity, through your Majesty’s gracious consideration, of reflecting upon this point, he humbly submits to your Majesty that he is reluctantly compelled, by a sense of public duty, and in interest of your Majesty’s service, to adhere to the opinion which he ventured to express to your Majesty.”

In a later portion of his speech, Sir Robert remarks:

“I, upon that very question of Ireland, should have begun in a minority of upwards of twenty members. A majority of twenty-two had decided in favour of the policy of the Irish Government. The chief members of the Irish Government, whose policy was so approved of, were the Marquis of Normanby and Lord Morpeth. By whom are the two chief offices in the household at this moment held? By the sister of Lord Morpeth, and the wife of Lord Normanby. Let me not, for a moment, be supposed to say a word not fraught with respect towards those two ladies, who cast a lustre on the society in which they move, less by their rank than their accomplishments and virtues; but still, they stand in the situation of the nearest relatives of the two Members of the Government, whose policy was approved by this House, and disapproved by me. Now, I ask any man in the House, whether it is possible that I could, with propriety and honour, undertake the conduct of an Administration, and the management of Irish affairs in this House, consenting previously, as an express preliminary stipulation, that the two ladies 1 have named, together with all others, should be retained in their appointments about the court and person of the Sovereign? Sir, the policy of these things depends not upon precedent – not upon what has been done in former times; it mainly depends upon a consideration of the present. The household has been allowed to assume a completely political character, and that on account of the nature of the appointments which have been made by Her Majesty’s present Government I do not complain of it – it may have been a wise policy to place in the chief offices of the household, ladies closely connected with the Members of the Administration; but, remember that this policy does seriously to the public embarrassment of their successors, if ladies, being the nearest relatives of the retired Ministers, are to continue in their offices about the person of the Sovereign.”

So Lord Melbourne, returned to power.

The genial Caricaturist John Doyle, as there were no illustrated comic papers in those days, illustrated this incident in his H. B. Sketches. No. 591 is “A Scene from the farce of The Invincibles, as lately performed in the Queen’s Theatre” – in which the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel are being expelled at the point of the bayonet, by ladies clad as soldiers. Sir Robert says: “These Household Troops charge in a most disorderly manner, but they are too many for us.” While the Duke observes: “Our position is no longer tenable; draw off in good order, while I cover the retreat.” No. 592 is “The Balance of Power. The figure proposed to displace the old one of Justice at the top of Constitution Hill.” It shows a statue of the Queen, as Justice, holding a pair of scales, in which “Private Friendship,” typified by two ladies of the household, weighs down “Public Service” full of Ministers. I have here reproduced No. 597, “Child’s Play,” in which figure the Queen, the Duchess of Sutherland, the Marchioness of Normanby, and other ladies of the household. No. 599 is a “Curious instance of (Ministerial) ‘Resuscitation,’ effected by distinguished members of the Royal Humane Society.” Lord Melbourne is lying on a couch, attended by the Queen and ladies of the household. The Queen holds a smelling bottle to his nose, and says: “Ah, there’s a dear, now do revive.”

Whether it was owing to this affair, or not, I know not, but at Ascot races this year the Queen was absolutely hissed at by some one, or more persons – and the Times of 25 June quotes from the Morning Post thus:

“At the last Ascot races, we have reason to believe that the Duchess of Montrose and Lady Sarah Ingestre received an intimation that Her Majesty was impressed with the idea that they were among the persons who had hissed at a moment when no sounds but those of applause, gratulation and loyalty ought to have been heard. It was, we believe, further intimated to the noble ladies we have mentioned, that the Royal ear had been abused, to the effect already stated, by Lady Lichfield. The ladies, who had reason to think that they had been thus unjustly and ridiculously accused, applied immediately to their supposed accuser, who denied that she had made any such communication. On being urged to give this denial in writing, she declined to do so without first consulting her lord. But, on the application being renewed at a subsequent period, her ladyship, as we understand, explicitly, and in writing, denied that she had given utterance to the calumny in question. Here the matter stood, until, from some incidents connected with the late ball at Buckingham Palace, the two ladies, thus impeached, saw reason to believe that the erroneous impression communicated to Her Majesty at Ascot had not been entirely removed. It was an impression, however, which they could not permit to remain without employing every means of removing it; and, accordingly, the Duchess of Montrose went to Buckingham Palace, and requested an audience of Her Majesty. After waiting for a considerable period (two hours, as we have been informed), her Grace was informed by the Earl of Uxbridge, that she could not be admitted to an audience, as none but Peers and Peeresses in their own right could demand that privilege. Her Grace then insisted upon Lord Uxbridge taking down in writing what she had to say, and promising her that the communication should immediately be laid before Her Majesty. In this state, we believe, the matter remains, substantially, at the present moment, although it has taken a new form, the Duke of Montrose having, we understand, thought it necessary to open a correspondence upon the subject with Lord Melbourne.”

There was only a partial denial given to the above, which appeared in the Times of 5 July. “We are authorised to give the most positive denial to a report which has been inserted in most of the public papers, that the Countess of Lichfield informed the Queen that the Duchess of Montrose and Lady Sarah Ingestre hissed Her Majesty on the racecourse at Ascot. Lady Lichfield never insinuated, or countenanced any such report, and there could have been no foundation for so unjust an accusation.”

Melbourne, in Australia (named, of course, after the Premier), was founded 1 June, 1837, and I mention the fact to shew the prosperity of the infant city – for in two years’ time, on this its second anniversary, certain lots of land had advanced in price from £7 to £600, and from £27 to £930.

I cannot help chronicling an amusing story anent Sunday trading. For some time the parish authorities of Islington had been rigidly prosecuting shopkeepers for keeping open their shops on Sunday, for the sale of their goods, such not being “a work of necessity, or mercy,” and numerous convictions were recorded. Most of the persons convicted were poor, and with large families, who sold tobacco, fruit, cakes and sweets, in a very humble way of business, and considerable discontent and indignation was manifested in the parish in consequence of such prosecutions; the outcry was raised that there was one law for the rich and another for the poor, and a party that strongly opposed the proceedings on the part of the parish, resolved to try the legality and justice of the question, by instituting proceedings against the vicar’s coachman, for “exercising his worldly calling on the Sabbath day,” by driving his reverend master to church, that not being a work of necessity, or mercy, as the reverend gentleman was able both to walk and preach on the same day. For this purpose a party proceeded to the neighbourhood of the vicar’s stables one Sunday, and watched the proceedings of the coachman, whom they saw harness his horses, put them to the carriage, go to the vicar’s house, take him up, and drive him to church, where he entered the pulpit, and preached his sermon. One day, the following week, they attended Hatton Garden Police Office and applied to Mr. Benett for a summons against the coachman. The magistrate, on hearing the nature of the application, told them it was a doubtful case, and the clerk suggested that if they laid their information the magistrate might receive it, and decide on the legal merits of the case. This was done, the summons was granted, and a day appointed for hearing the case.

This took place on June 14, when John Wells, coachman to the vicar of Islington, appeared to answer the complaint of Frederick Hill, a tobacconist, for exercising his worldly calling on the Sabbath day.

John Hanbury, grocer, of 3, Pulteney Street, being sworn, stated that, on Sunday, the 9th inst, about 1 o’clock, he saw the defendant, who is coachman to the vicar of Islington, drive his coach to the Church of St. Mary, Islington, where he took up the vicar and his lady, and drove them to their residence in Barnsbury Park.

Mr. Benett: Are you sure it was the vicar?

Witness: I heard him preach.

John Jones, of Felix Terrace, Islington, corroborated this evidence.

Mr. Benett said, that the Act of Parliament laid down that no tradesman, labourer, or other person shall exercise his worldly calling on the Lord’s day, it not being a work of necessity or charity. He would ask whether it was not a work of necessity for the vicar to proceed to church to preach. A dissenter might say it was not a work of necessity. The coachman was not an artificer who was paid by the hour or the day, but he was engaged by the year, or the quarter, and was not to be viewed in the light of a grocer, or tradesman, who opened his shop for the sale of his goods on the Sabbath day. After explaining the law upon the subject, he said that he was of opinion that the defendant driving the vicar to church on Sundays, to perform his religious duties, was an act of necessity, and did not come within the meaning of the law, and he dismissed the case.

The clergy did not seem to be much in favour with their flocks, for I read in the Annual Register, 1 Aug., of “A New Way of Paying Church Rates. – Mr. Osborne, a dissenter, of Tewkesbury, having declined to pay Church Rates, declaring that he could not conscientiously do so, a sergeant and two officers of the police went to his house for the purpose of levying under a distress warrant to the amount due from him. The officers were asked to sit down, which they did, and Mr. Osborne went into his garden, procured a hive of bees, and threw it into the middle of the chamber. The officers were, of course, obliged to retreat, but they secured enough of the property to pay the rate, and the costs of the levy, besides which, they obtained a warrant against Mr. Osborne, who would, most likely, pay dearly for his new and conscientious method of settling Church Rate accounts.”

CHAPTER X

The Eglinton Tournament – Sale of Armour, &c. – The Queen of Beauty and her Cook – Newspapers and their Sales.

The Earl of Eglinton had a “bee in his bonnet,” which was none other than reviving the tournaments of the Age of Chivalry, with real armour, horses and properties; and he inoculated with his craze most of the young aristocracy, and induced them to join him in carrying it out. The preliminary rehearsals took place in the grounds of the Eyre Arms Tavern, Kilburn. The last of these came off on 13 July, in the presence of some 6,000 spectators, mostly composed of the aristocracy. The following is a portion of the account which appeared in the Times of 15 July:

“At 4 o’clock the business of the day commenced. There might be seen men in complete steel, riding with light lances at the ring, attacking the ‘quintain,’ and manœuvering their steeds in every variety of capricole. Indeed, the show of horses was one of the best parts of the sight. Trumpeters were calling the jousters to horse, and the wooden figure, encased in iron panoply, was prepared for the attack. A succession of chevaliers, sans peur et sans reproche, rode at their hardy and unflinching antagonist, who was propelled to the combat by the strength of several stout serving-men, in the costume of the olden time, and made his helmet and breastplate rattle beneath their strokes, but the wooden

.. Knight

Was mickle of might,

And stiff in Stower did stand,

grinning defiance through the barred aventaile of his headpiece. It was a sight that might have roused the spirit of old Froissart, or the ghost of Hotspur. The Knight had, certainly, no easy task to perform; the weight of armour was rather heavier than the usual trappings of a modern dandy, and the heat of the sun appeared to be baking the bones of some of the competitors. Be this as it may, there was no flinching. The last part of the tournament consisted of the Knights tilting at each other. The Earl of Eglinton, in a splendid suit of brass armour, with garde de reins of plated chain mail, and bearing on his casque a plume of ostrich feathers, was assailed by Lord Cranstoun, in a suit of polished steel, which covered him from top to toe, the steel shoes, or sollarets, being of the immense square-toed fashion of the time of Henry VIII. The lances of these two champions were repeatedly shivered in the attack, but neither was unhorsed; fresh lances were supplied by the esquires, and the sport grew ‘fast and furious.’ Lord Glenlyon and another knight, whose armour prevented him from being recognized, next tilted at each other, but their horses were not sufficiently trained to render the combat as it ought to have been, and swerved continually from the barrier. It was nearly eight o’clock before the whole of the sports were concluded and the company withdrawn. We believe no accident happened, though several gentlemen who essayed to ‘witch the world with noble horsemanship’ were thrown, amidst the laughter of the spectators. Captain Maynard proved himself a superior rider, by the splendid style at which he leaped his horse, at speed, repeatedly over the barrier, and the admirable manner in which he performed the modern lance exercise, and made a very beautiful charger curvet round and round his lance placed upright on the ground. The whole of the arrangements were under the direction of Mr. Pratt, to whose discretion the ordering of the tilting, the armour and arming, and all the appliances for the tournament have been entrusted.

“Considering that the business of Saturday was but a rehearsal, and, putting entirely out of the question the folly, or wisdom, of the whole thing, it must be acknowledged that it has been well got up. Some of the heralds’ and pursuivants’ costumes are very splendid. There is an immense store of armour of all sorts, pennons, lances, trappings, and all the details of the wars of the middle ages. The display in Scotland will, certainly, be a gorgeous pageant, and a most extraordinary, if not most rational, piece of pastime.”

The three days’ jousting and hospitality at Eglinton Castle, Ayrshire, which commenced on the 28th, and ended on the 30th, August, are said to have cost the Earl of Eglinton the sum of £40,000. He invited the flower of the aristocracy to attend – all the armour was choice and old, and the costumes were splendid. Every accessory was perfect in its way; and so it should have been, for it was two years in preparation. The Marquis of Londonderry was King of the Tourney, and Lady Seymour, a grand-daughter of the Sheridan, was the “Queen of Love and Beauty.”

By the evening of the 27th, Eglinton Castle was not only filled from cellar to garret, but the surrounding towns and villages were crammed full, and people had to rough it. Accommodation for man, or beast, rose from 500 to 1,000 per cent.; houses in the neighbourhood, according to their dimensions, were let from £10 to £30 for the time; and single beds, in the second best apartments of a weaver’s cabin, fetched from 10/– to 20/– a night, while the master and mistress of the household, with their little ones, coiled themselves up in any out of the way corner, as best they might. Stables, byres, and sheds were in requisition for the horses, and, with every available atom of space of this description, it was found all too little, as people flocked from all parts of the country.

The invitation given by the Earl was universal. Those who applied for tickets of admission to the stands were requested to appear in ancient costume, fancy dresses, or uniforms, and farmers and others were asked to appear in bonnets and kilts, and many – very many – did so; but although all the bonnet makers in Kilmarnock, and all the plaid manufacturers in Scotland, had been employed from the time of the announcement, onwards, they could not provide for the wants of the immense crowd, and many had to go in their ordinary dress.

Unfortunately, on the opening day, the weather utterly spoilt the show. Before one o’clock, the rain commenced, and continued, with very little intermission, until the evening. This, necessarily, made it very uncomfortable for all, especially the spectators. Many thousands left the field, and the enjoyment of those who remained was, in a great measure, destroyed. The Grand Stand, alone, was covered in, and neither plaid, umbrella, nor great-coat could prevail against a deluge so heavy and unintermitting; thousands were thoroughly drenched to the skin; but the mass only squeezed the closer together, and the excitement of the moment overcame all external annoyances, although the men became sodden, and the finery of the ladies sadly bedraggled.

It had been arranged that the procession should start from the Castle at one o’clock, but the state of the weather was so unfavourable, that it did not issue forth till about half-past two, and the weather compelled some modifications; for instance, the Queen of Beauty should have shown herself “in a rich costume, on a horse richly caparisoned, a silk canopy borne over her by attendants in costume,” but both she, and her attendant ladies, who were also to have been on horseback, did not so appear, but were in closed carriages, whilst their beautifully caparisoned palfreys – riderless – were led by their pages.

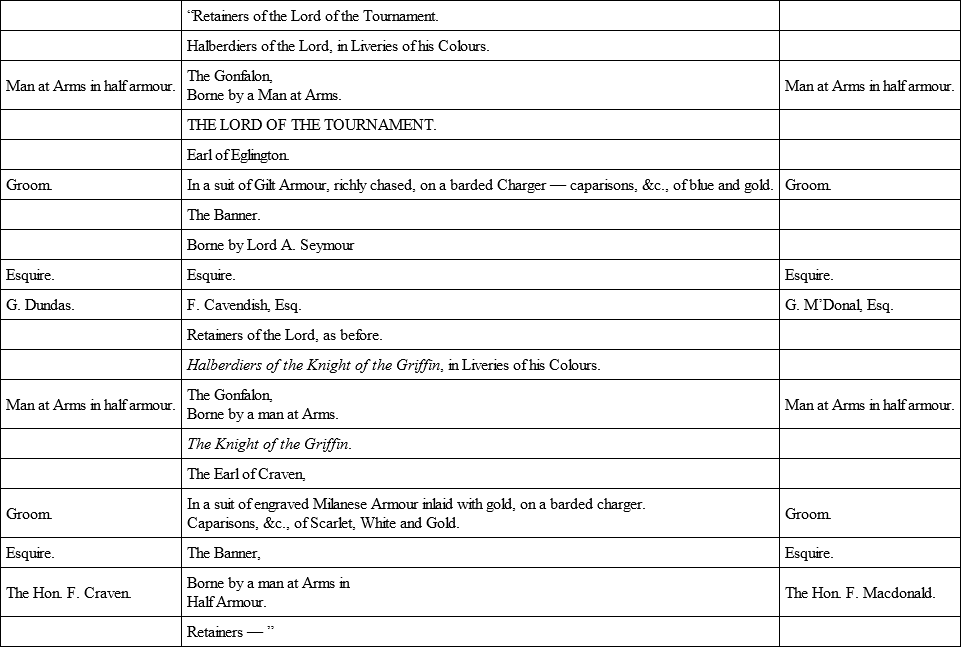

There were 15 Knights, besides the “Lord of the Tournament,” the Earl of Eglinton, and much as I should like to give their description and following, I must refrain, merely giving two as a sample —

The other Knights were: —The Knight of the Dragon, Marquis of Waterford; Knight of the Black Lion, Viscount Alford; Knight of Gael, Viscount Glenlyon; Knight of the Dolphin, Earl of Cassilis; Knight of the Crane, Lord Cranstoun; Knight of the Ram, Hon. Capt. Gage; The Black Knight, John Campbell, Esq., of Saddell; Knight of the Swan, Hon. Mr. Jerningham; Knight of the Golden Lion, Capt. J. O. Fairlie; Knight of the White Rose, Charles Lamb, Esq.; Knight of the Stag’s Head, Capt. Beresford; The Knight of the Border, Sir F. Johnstone; Knight of the Burning Tower, Sir F. Hopkins; The Knight of the Red Rose, R. J. Lechmere, Esq.; Knight of the Lion’s Paw, Cecil Boothby, Esq.

There were, besides, Knights Visitors, Swordsmen, Bowmen, the Seneschal of the Castle, Marshals and Deputy Marshals, Chamberlains of the household, servitors of the Castle, a Herald and two Pursuivants, a Judge of Peace, and a Jester – besides a horde of small fry.

The first tilt was between the Knights of the Swan and the Red Rose, but it was uninteresting, the Knights passing each other twice, without touching, and, on the third course, the Knight of the Swan lost his lance.

Then came the tilt of the day, when the Earl of Eglinton met the Marquis of Waterford. The latter was particularly remarked, as the splendour of his brazen armour, the beauty of his charger, and his superior skill in the management of the animal, as well as in the bearing of his lance, attracted general observation. But, alas! victory was not to be his, for, in the first tilt, the Earl of Eglinton shivered his lance on his opponent’s shield, and was duly cheered by all. In the second, both Knights missed; but, in the third, the Earl again broke his lance on his opponent’s armour; at which there was renewed applause from the multitude; and, amidst the cheering and music, the noble Earl rode up to the Grand Stand, and bowed to the Queen of Beauty.

There were three more tilts, and a combat of two-handed swords, which finished the outdoor amusements of the day, and, when the deluged guests found their way to the Banqueting Hall, they found that, and its sister tent, the Ballroom, utterly untenantable through the rain; so they had to improvise a meal within the Castle, and the Ball was postponed.

Next day was wild with wind and rain, and nothing could be attempted out of doors, as the armour was all wet and rusty, and every article of dress that had been worn the preceding day completely soaked through, and the Dining Hall and the Great Pavilion required a thorough drying. The former was given up to the cleansing of armour, etc., and, in the latter, there were various tilting matches on foot, the combatants being clothed in armour. There was also fencing, both with sticks and broadsword, among the performers being Prince Louis Bonaparte, afterwards Napoleon III. His opponent with the singlesticks was a very young gentleman, Mr. Charteris, and the Prince came off second best in the encounter, as he did, afterwards, in some bouts with broadswords with Mr. Charles Lamb. Luckily, in this latter contest, both fought in complete mail, with visors down, for had it not been so, and had the combat been for life or death, the Prince would have had no chance with his opponent.

On the third day the weather was fine, and the procession was a success. There was tilting between eight couples of Knights, and tilting at the ring, and the tourney wound up with the Knights being halved, and started from either end of the lists, striking at each other with their swords in passing. Only one or two cuts were given, but the Marquis of Waterford and Lord Alford fought seriously, and in right good earnest, until stopped by the Knight Marshal, Sir Charles Lamb.

In the evening, a banquet was given to 300 guests; and, afterwards, a ball, in which 1,000 participated. As the weather, next day, was so especially stormy, the party broke up, and the experimental revival has never again been attempted, except a Tourney on a much smaller scale, which was held on 31 Oct., 1839, at Irvine, by a party from Eglinton Castle; but this only lasted one day.

I regret that I have been unable to find any authentic engravings of this celebrated tournament, but I reproduce a semi-comic contemporaneous etching from the Satirical Prints, Brit. Mus.

The armour and arms used in this tournament were shown in Feb., 1840, at the Gallery of Ancient Armour in Grosvenor Street, and they were subsequently sold by Auction on July 17 and 18 of that year. They fetched ridiculously low prices, as the following example will show:

A suit of polished steel cap à pied armour, richly engraved and gilt, being the armour prepared for the Knight of the Lion’s Paw, with tilting shield, lance, plume and crest en suite, 32 guineas.

The emblazoned banner and shield of the Knight of the Burning Tower, with the suit of polished steel, cap-à-pied armour, with skirt of chain mail, 35 guineas.