Полная версия

Полная версияEighteenth Century Waifs

On the 1st of January, 1788, was born a baby that has since grown into a mighty giant. On that day was published the first number of the Times, or Daily Universal Register, for it had a dual surname, and the reasons for the alteration are given in the following ‘editorial.’

‘The Times‘Why change the head?

‘This question will naturally come from the Public – and we, the Times, being the Public’s most humble and obedient Servants, think ourselves bound to answer: —

‘All things have heads– and all heads are liable to change.

‘Every sentence and opinion advanced by Mr. Shandy on the influence and utility of a well-chosen surname may be properly applied in showing the recommendations and advantages which result from placing a striking title-page before a book, or an inviting Head on the front page of a Newspaper.

‘A Head so placed, like those heads which once ornamented Temple Bar, or those of the great Attorney, or great Contractor, which, not long since, were conspicuously elevated for their great actions, and were exhibited, in wooden frames, at the East and West Ends of this Metropolis, never fails of attracting the eyes of passengers – though, indeed, we do not expect to experience the lenity shown to these great exhibitors, for probably the Times will be pelted without mercy.

‘But then, a head with a good face is a harbinger, a gentleman-usher, that often strongly recommends even Dulness, Folly, Immorality, or Vice. The immortal Locke gives evidence to the truth of this observation. That great philosopher has declared that, though repeatedly taken in, he never could withstand the solicitations of a well-drawn title-page – authority sufficient to justify us in assuming a new head and a new set of features, but not with a design to impose; for we flatter ourselves the Head of the Times will not be found deficient in intellect, but, by putting a new face on affairs, will be admired for the light of its countenance, whenever it appears.

‘To advert to our first position.

‘The Universal Register has been a name as injurious to the Logographic Newspaper, as Tristram was to Mr. Shandy’s Son. But Old Shandy forgot he might have rectified by confirmation the mistakes of the parson at baptism– with the touch of a Bishop have changed Tristram to Trismegistus.

‘The Universal Register, from the day of its first appearance to the day of its confirmation, has, like Tristram, suffered from unusual casualties, both laughable and serious, arising from its name, which, on its introduction, was immediately curtailed of its fair proportion by all who called for it – the word Universal being Universally omitted, and the word Register being only retained.

‘“Boy, bring me the Register.”

‘The waiter answers: “Sir, we have not a library, but you may see it at the New Exchange Coffee House.”

‘“Then I’ll see it there,” answers the disappointed politician; and he goes to the New Exchange, and calls for the Register; upon which the waiter tells him he cannot have it, as he is not a subscriber, and presents him with the Court and City Register, the Old Annual Register, or, if the Coffee-house be within the Purlieus of Covent Garden, or the hundreds of Drury, slips into the politician’s hand Harris’s Register of Ladies.

‘For these and other reasons the parents of the Universal Register have added to its original name that of the

TIMES,Which, being a monosyllable, bids defiance to corrupters and mutilaters of the language.

‘The Times! What a monstrous name! Granted, for the Times is a many-headed monster, that speaks with an hundred tongues, and displays a thousand characters, and, in the course of its transformations in life, assumes innumerable shapes and humours.

‘The critical reader will observe we personify our new name; but as we give it no distinction of sex, and though it will be active in its vocations, yet we apply to it the neuter gender.

‘The Times, being formed of materials, and possessing qualities of opposite and heterogeneous natures, cannot be classed either in the animal or vegetable genus; but, like the Polypus, is doubtful, and in the discussion, description, dissection, and illustration will employ the pens of the most celebrated among the Literati.

‘The Heads of the Times, as has been said, are many; they will, however, not always appear at the same time, but casually, as public or private affairs may call them forth.

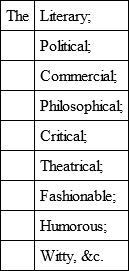

‘The principal, or leading heads are —

‘Each of which are supplied with a competent share of intellects for the pursuit of their several functions; an endowment which is not in all times to be found even in the Heads of the State, the heads of the Church, the heads of the Law, the heads of the Navy, the heads of the Army, and though last, not least, the great heads of the Universities.

‘The Political Head of the Times, like that of Janus, the Roman Deity, is doubly faced; with one countenance it will smile continually on the friends of Old England, and with the other will frown incessantly on her enemies.

‘The alteration we have made in our head is not without precedents. The World has parted with half its Caput Mortuum, and a moiety of its brains. The Herald has cut off half its head, and has lost its original humour. The Post, it is true, retains its whole head and its old features; and, as to the other public prints, they appear as having neither heads nor tails. On the Parliamentary Head every communication that ability and industry can produce may be expected. To this great National object, the Times will be most sedulously attentive, most accurately correct, and strictly impartial in its reports.’

The early career of the Times was not all prosperity, and Mr. Walter was soon taught a practical lesson in keeping his pen within due bounds, for, on July 11th, 1788, he was tried for two libellous paragraphs published in the Times, reflecting on the characters of the Duke of York, Gloucester, and Cumberland, stating them to be ‘insincere’ in their profession of joy at his Majesty’s recovery. It might have been an absolute fact, but it was impolitic to print it, and so he found it, for a jury found him guilty.

He came up for judgment at the King’s Bench on the 23rd of November next, when he was sentenced by the Court to pay a fine of fifty pounds, to be imprisoned twelve months in Newgate, to stand in the pillory at Charing Cross, when his punishment should have come to an end, and to find security for his good behaviour.

He seems to have ridden a-tilt at all the royal princes, for we next hear of him under date of 3rd of February, 1790, being brought from Newgate to the Court of King’s Bench to receive sentence for the following libels:

For charging their Royal Highnesses the Prince of Wales and Duke of York with having demeaned themselves so as to incur the displeasure of his Majesty. This, doubtless, was strictly true, but it cost the luckless Walter one hundred pounds as a fine, and another twelve months’ imprisonment in Newgate.

This, however, was not all; he was arraigned on another indictment for asserting that His Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence returned from his station without leave of the Admiralty, or of his commanding officer, and for this he was found guilty, and sentenced to pay another hundred pounds.

Whether he made due submission, or had powerful friends to assist him, I know not, – but it is said that it was at the request of the Prince of Wales – at all events, he received the king’s pardon, and was released from confinement on 7th of March, 1791, after which time he never wrote about the king’s sons in a way likely to bring him within the grip of the Law.

From time to time we get little avisos as to the progress of the paper, for John Walter was not one of those who hide their light under a bushel. Contrast the printing power then with the magnificent ‘Walter’ machines of the present day, which, in their turn, will assuredly be superseded by some greater improvement.

The Times, 7th of February, 1794. ‘The Proprietors have for some time past been engaged in making alterations which they trust will be adequate to remedy the inconvenience of the late delivery complained of; and after Monday next the Times will be worked off with three Presses, and occasionally with four, instead of TWO, as is done in all other Printing-offices, by which mode two hours will be saved in printing the Paper, which, notwithstanding the lateness of the delivery, is now upwards of Four Thousand Three Hundred in sale, daily.’

The following statement is curious, as showing us some of the interior economy of the newspaper in its early days. From the Times, April 19, 1794:

‘To the Public‘It is with very great regret that the Proprietors of this Paper, in Common with those of other Newspapers, find themselves obliged to increase the daily price of it One Halfpenny, a measure which they have been forced to adopt in consequence of the Tax laid by the Minister on Paper, during the present Session of Parliament, and which took place on the 5th instant.

‘While the Bill was still pending, we not only stated in our Newspaper, but the Minister was himself informed by a Committee of Proprietors, that the new Duty would be so extremely oppressive as to amount to a necessity of raising the price, which it was not only their earnest Wish, but also their Interest, to avoid. The Bill, however, passed, after a long consideration and delay occasioned by the great doubts that were entertained of its efficacy. We wish a still longer time had been taken to consider it; for we entertain the same opinion as formerly, that the late Duty on Paper will not be productive to the Revenue, while it is extremely injurious to a particular class of Individuals, whose property was very heavily taxed before.

‘In fact, it amounts either to a Prohibition of printing a Newspaper at the present price, or obliges the Proprietors to advance it. There is no option left; the price of Paper is now so high that the Proprietors have no longer an interest to render their sale extensive, as far as regards the profits of a large circulation. The more they sell at the present price, the more they will lose; to us alone the Advance on Paper will make a difference of £1,200 sterling per Annum more than it formerly cost us – a sum which the Public must be convinced neither can, nor ought to be afforded by any Property of the limited nature of a Newspaper, the profits on the sale of which are precisely as follows:

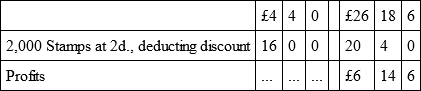

‘Sale2,000 Newspapers sold to the Newshawkers at 3½d., with a further deduction of allowing them a Paper in every Quire … ... … £26 18 6.

‘Cost of 2,000 PapersA Bundle of Paper containing 2,000 Half-sheets, or 2,000 Newspapers at Four Guineas per Bundle, which is the price it will be sold at under the new Duty is £4 4 0.

‘This is the whole Profit on the sale of two thousand Newspapers, out of which is to be deducted the charges of printing a Newspaper (which, on account of the Rise in Printers’ Wages last year, is £100 a year more than it ever was before), the charges of Rent, Taxes, Coals, Candles (which are very high in every Printing-office), Clerks, general Superintendance, Editing, Parliamentary and Law Reports, and, above all, the Expenses of Foreign Correspondence, which, under the present difficulties of obtaining it, and the different Channels which must be employed to secure a regular and uninterrupted Communication, is immense. If this Paper is in high estimation, surely the Proprietors ought to receive the advantage of their success, and not the Revenue, which already monopolises such an immense income from this property, no less than to the amount of £14,000 sterling during last year only. We trust that these reasons will have sufficient weight with the Public to excuse us when we announce, though with very great regret, that on Monday next the price of this Paper will be Fourpence Halfpenny.’

Occasionally, the proprietor fell foul of his neighbours; vide the Times, November 16, 1795:

‘All the abuse so lavishly bestowed on this Paper by other Public Prints, seems as if designed to betray, that in proportion as our sale is good, it is bad Times with them.’

In the early part of 1797, Pitt proposed, among other methods of augmenting the revenue, an additional stamp of three halfpence on every newspaper. The Times, April 28, 1797, groaned over it thus:

‘The present daily sale of the Times is known to be between four and five thousand Newspapers. For the sake of perspicuity, we will make our calculation on four thousand only, and it will hold good in proportion to every other Paper.

‘The Newsvendors are now allowed by the Proprietors of every Newspaper two sheets in every quire, viz., twenty-six for every twenty-four Papers sold. The stamp duty on two Papers in every quire in four thousand Papers daily at the old Duty of 2d., amounts to £780 a year, besides the value of the Paper. An additional Duty of 1½d. will occasion a further loss of £585 in this one instance only, for which there is not, according to Mr. Pitt’s view of the subject, to be the smallest remuneration to the Proprietors. Is it possible that anything can be so unjust? If the Minister persists in his proposed plan, it will be impossible for Newspapers to be sold at a lower rate than sixpence halfpenny per Paper.’

Pitt, of course, carried out his financial plan, and the newspapers had to grin, and bear it as best they could – the weaker going to the wall, as may be seen by the following notices which appeared in the Times, July 5:

‘To the Public.

‘We think it proper to remind our Readers and the Public at large that, in consequence of the heavy additional Duty of Three Half-pence imposed on every Newspaper, by a late Act of Parliament, which begins to have effect from and after this day, the Proprietors are placed in the very unpleasant position of being compelled to raise the price of their Newspapers to the amount of the said Duty. To the Proprietors of this Paper it will prove a very considerable diminution of the fair profits of the Trade; they will not, however, withdraw in the smallest degree any part of the Expenses which they employ in rendering the Times an Intelligent and Entertaining source of Information: and they trust with confidence that the Public will bestow on it the same liberal and kind Patronage which they have shown for many years past; and for which the Proprietors have to offer sentiments of sincere gratitude. From this day, the price of every Newspaper will be Sixpence.’

July 19, 1797. ‘Some of the Country Newspapers have actually given up the Trade, rather than stand the risk of the late enormous heavy Duty: many others have advertised them for Sale: some of those printed in Town must soon do the like, for the fair profits of Trade have been so curtailed, that no Paper can stand the loss without having a very large proportion of Advertisements. We have very little doubt but that, so far from Mr. Pitt’s calculation of a profit of £114,000 sterling by the New Tax on Newspapers, the Duty, the same as on Wine, will fall very short of the original Revenue.’

July 13, 1797. ‘As a proof of the diminution in the general sale of Newspapers since the last impolitic Tax laid on them, we have to observe, as one instance, that the number of Newspapers sent through the General Post Office on Monday the 3rd instant, was 24,700, and on Monday last, only 16,800, a falling off of nearly one-third.’

Once again we find John Walter falling foul of a contemporary – and indulging in editorial amenities.

July 2, 1798. ‘The Morning Herald has, no doubt, acted from very prudent motives in declining to state any circumstances respecting its sale. All that we hope and expect, in future, is – that it will not attempt to injure this Paper by insinuating that it was in a declining state; an assertion which it knows to be false, and which will be taken notice of in a different way if repeated. The Morning Herald is at liberty to make any other comments it pleases.’

Have the Daily Telegraph and the Standard copied from John Walter, when they give public notice that their circulation is so-and-so, as is vouched for by a respectable accountant? It would seem so, for this notice appeared in the Times:

‘We have subjoined an Affidavit sworn yesterday before a Magistrate of the City, as to the present sale of the Times.

‘“We, C. Bentley and G. Burroughs, Pressmen of the Times, do make Oath, and declare, That the number printed of the Times Paper for the last two months, has never been, on any one day, below 3 thousand, and has fluctuated from that number to three thousand three hundred and fifty.”

‘And, in order to avoid every subterfuge, I moreover attest, That the above Papers of the Times were paid for to me, previous to their being taken by the Newsmen from the Office, with the exception of about a dozen Papers each morning which are spoiled in Printing.

‘J. Bonsor, Publisher. ‘Sworn before me December 31, 1798. ‘W. Curtis.’

From this time the career of the Times seems to have been prosperous, for we read, January 1, 1799,

‘The New Year‘The New Year finds the Times in the same situation which it has invariably enjoyed during a long period of public approbation. It still continues to maintain its character among the Morning Papers, as the most considerable in point of sale, as of general dependence with respect to information, and as proceeding on the general principles of the British Constitution. While we thus proudly declare our possession of the public favour, we beg leave to express our grateful sense of the unexampled patronage we have derived from it.’

Mr. John Walter was never conspicuous for his modesty, and its absence is fully shown in the preceding and succeeding examples (January 1, 1800):

‘It is always with satisfaction that we avail ourselves of the return of the present Season to acknowledge our sense of the obligation we lay under to the Public, for the very liberal Patronage with which they have honoured the Times, during many years; a constancy of favour, which, we believe, has never before distinguished any Newspaper, and for which the Proprietors cannot sufficiently express their most grateful thanks.

‘This Favour is too valuable and too honourable to excite no envy in contemporary Prints, whose frequent habit it is to express it by the grossest calumnies and abuse. The Public, we believe, has done them ample justice, and applauded the contempt with which it is our practice to receive them.’

As this self-gratulatory notice brings us down to the last year of the eighteenth century, I close this notice of ‘The Times and its Founder.’ John Walter died at Teddington, Middlesex, on the 26th of January, 1812.

IMPRISONMENT FOR DEBT

Imprisonment for debt has long ceased to exist in England; debtors now only suffering incarceration for contempt of Court: that is to say, that the judge has satisfied himself that the debtor has the means to pay, and will not. But, in the eighteenth century, it was a fearful fact, and many languished in prison for life, for most trifling sums. Of course, there were debtors and debtors. If a man had money or friends, much might be done to mitigate his position; he might even live outside the prison, in the Rules, as they were called, a limited district surrounding the prison; but for this advantage he must find substantial bail – enough to cover his debt and fees. But the friendless poor debtor had a very hard lot, subsisting on charity, going, in turn, to beg of passers-by for a coin, however small, rattling a box to call attention, and dolorously repeating, ‘Remember the poor prisoners.’

There were many debtors’ prisons, and one of the principal, the Fleet, was over-crowded; in fact, they all were full. Newgate, the Marshalsea, the Gate House, Westminster, the Queen’s Bench, the Fleet, Ludgate, Whitecross Street, Whitechapel, and a peculiar one belonging to St. Katharine’s (where are now the docks).

Arrest for debt was very prompt; a writ was taken out, and no poor debtor dare stir out without walking ‘beard on shoulder,’ dreading a bailiff in every passer-by. The profession of bailiff was not an honoured one, and, probably, the best men did not enter it; but they had to be men of keen wit and ready resource, for they had equally keen wits, sharpened by the dread of capture, pitted against them. Some rose to eminence in their profession, and as, occasionally, there is a humorous side even to misery, I will tell a few stories of their exploits. As I am not inventing them, and am too honest to pass off another man’s work as my own, I prefer telling the stories in the quaint language in which I find them.

‘Abram Wood had a Writ against an Engraver, who kept a House opposite to Long Acre in Drury Lane, and having been several times to serve it, but could never light on the Man, because he work’d at his business above Stairs, as not daring to shew his Head for fear of being arrested, for he owed a great deal of Money, Mr. Bum was in a Resolution of spending no more Time over him; till, shortly after, hearing that one Tom Sharp, a House-breaker, was to be hang’d at the end of Long Acre, for murdering a Watchman, he and his Follower dress’d themselves like Carpenters, having Leather Aprons on, and Rules tuck’d in at the Apron Strings: then going early the morning or two before the Malefactor was to be executed, to the place appointed for Execution, they there began to pull out their Rules, and were very busie in marking out the Ground where they thought best for erecting the Gibbet. This drew several of the Housekeepers about ’em presently, and among the rest the Engraver, who, out of a selfish humour of thinking he might make somewhat the more by People standing in his House to see the Execution, in Case this Gibbet was near it, gave Abram a Crown, saying,

‘“I’ll give you a Crown more if you’ll put the Gibbet hereabouts;” at the same time pointing where he would have it.

‘Quoth Abram: “We must put it fronting exactly up Long Acre; besides, could I put it nearer your door, I should require more Money than you propose, even as much as this” (at the same time pulling it out of his pocket) “Writ requires, which is twenty-five Pounds.” So, taking his prisoner away, who could not give in Bail to the Action, he was carried to Jayl, without seeing Tom Sharp executed.’

‘William Browne had an Action given him against one Mark Blowen, a Butcher, who, being much in debt, was never at his Stall, except on Saturdays, and then not properly neither, for the opposite side of the way to his Shop being in the Duchy Liberty44 (with the Bailiff whereof he kept in Fee) a Bailiff of the Marshal’s Court could not arrest him. From hence he could call to his Wife and Customers as there was occasion; and there could Browne once a week see his Prey, but durst not meddle with him. Many a Saturday his Mouth watered at him; but one Saturday above the rest, Browne, stooping for a Purse, as if he found it, just by his Stall, and pulling five or six guineas out of it, the Butcher’s Wife cry’d “Halves;” his Follower, who was at some little distance behind him, cry’d out, “Halves” too.

‘Browne refused Halves to either, whereupon they both took hold of him, the Woman swearing it was found by her Stall, therefore she would have half; and the Follower saying, As he saw it as soon t’other, he would have a Share of it too, or he would acquaint the Lord of the Mannor with it. Mark Blowen, in the meantime, seeing his Wife and another pulling and haling the Man about, whom he did not suspect to be a Bailiff, asked, “What’s the Matter?” His wife telling him the Man had found a Purse with Gold in it by her Stall, and therefore she thought it nothing but Justice but she ought to have some of it.