Полная версия

Полная версияPsychotherapy

That the good prognosis of these cases which I suggest is not forced and is not over-favorable nor the result of the wish to soothe patients may be judged from recent studies of the heart as well as from the older ones. In discussing extra-systole, MacKenzie in his "Diseases of the Heart,"27 says:

Dyspeptic and neurotic people are often liable [to suffer from them]. That other conditions give rise to extra-systoles, is also evident from the fact that they may occur in young people in whom there is no rheumatic history and no cardiosclerosis and whose after-history reveals no sign of heart trouble.

It is well to note the frequency of such annoying symptoms in those who have gone through rheumatic fever, and where patients have a history of this it is well to be cautious, but even in these cases he says that the trouble is often entirely neurotic and the one important preliminary to any successful treatment is to get the patient's mind off his condition, improve his general nervous state, and above all relieve as far as possible the gastric symptoms that may be present.

He says further:

Some patients are conscious of a quiet transient fluttering in the chest when an extra-systole occurs; others are aware of the long pause, "as if their hearts had stopped"; while others are conscious of the big beat that frequently follows the long pause. So violent is the effect of this after-beat, that in neurotic persons it may cause a shock, followed by a sense of great exhaustion. Most patients are unconscious of the irregularity due to the extra-systole until their attention is called to it by the medical attendant. Both being ignorant of its origin, and its being characteristic of human nature to associate the unknown with evil, patient and doctor are too often unnecessarily alarmed.

Cardiac Stomach Disturbance.—On the other hand, as a word of warning, it seems necessary to say here that later in life acute conditions manifesting themselves through the stomach are often of cardiac origin. Most physicians have been called to see some old man who had partaken of a favorite dish which did not, however, always agree with him and who suffered as a consequence from what at first was thought to be acute gastritis. The severity of the symptoms and the almost immediate collapse without any question of ptomaine poisoning, however, usually make it clear that some other organ is at fault besides the stomach itself. The real etiological train seems to be that a weakened heart sometimes without any valve lesion but with a muscular or vascular degeneration hampering its activity is further seriously disturbed by the overloading of the stomach. The result is a failure for the moment of circulation in the digestive organs with consequent rejection of the contents of the tract, nature's method of relieving herself of substances that cannot be properly prepared for absorption. Unfortunately, the condition sometimes proves so severe a shock to the weakened heart that it stops beating, and the physician is brought face to face with a death from "heart failure."

In these cases it is important to remember that the gastric disturbance may so mask the heart symptoms as completely to deceive the physician. The prognosis of these cases, however, is most serious. It seems worth while to give a warning with regard to these cases, because anything that we may have to say as to the relations of the stomach and the heart and the possibility of lessening the cardiac depression due to unfavorable mental influence when palpitation occurs as a consequence of gastric distention, has nothing to do with these acute cases in older patients where the condition is serious and the prognosis by no means favorable.

Treatment.—The rôle of psychotherapy in this form of cardiac disturbance associated with gastro-intestinal affections is, after the differentiation of neurotic from serious organic conditions, to give the patient such reassurance as is justified by his condition. It is surprising how many people are worrying about their hearts because their stomachic and intestinal conditions give rise to heart palpitation, that is to such action of the heart as brings it into the sphere of their consciousness, sometimes with the complication of intermittency or even more marked irregularity. The less the experience of the physician the more serious is he likely to consider these conditions and the more likely he is to disturb the patient by his diagnosis and prognosis. Until there is some sign of failing circulation, or of beginning disturbance of compensation, the attachment of a serious significance to these conditions always makes patients worse and removes one of the most helpful forms of therapeusis, that of the favorable influence of the mind on the heart. On the other hand, unless the patients' own unfavorable auto-suggestions as regards the significance of their heart symptoms are corrected, these people not only suffer subjectively, but bring about such disturbance of their physical condition as makes many symptoms objective.

While there are serious affections in which heart and stomach are closely associated, these are quite rare and usually manifest themselves in acute conditions and in old people. In the chapter on Angina Pectoris attention is called to the fact that there are may forms of pseudo-angina due to cardiac neuroses consequent upon gastric disturbance and without heart lesion. Broadbent has not hesitated to say that these forms of angina cause more suffering or at least produce more reaction on the part of the patient and are always the source of more complaint than the paroxysms due to serious cardiac conditions which present the constant possibility of a fatal termination.

Where the stomach is the cause of the cardiac neuroses psychotherapy is an extremely important element in the treatment. The continuance and exaggeration of their symptoms is often due to a disturbance of mind consequent upon the feeling that they have some serious form of heart disease. Without definite reassurance in this matter all the experts in heart disease insist that it is extremely difficult to bring about relief of symptoms in these patients. Whenever the general health of the individual has not suffered from his heart affection, it is quite safe to assume that no organic disease of the heart is present, no matter what the symptoms, for, as Broadbent and many other authorities emphasize, gastric cardiac neuroses can simulate every form of heart disturbance. The older physicians insisted that what they called sympathy with the hypochondriac organs might produce all sorts of heart symptoms. The patient must be told this confidently. The slightest exaggeration of the significance of his symptoms can do no possible good and will always do positive harm.

After reassurance, the most important thing is, of course, regulation of the diet and of the digestive functions generally. Unfortunately, regulation of the diet to many patients and even to many physicians seems to mean the limitation of diet. I have seen sufferers from cardiac symptoms have these increased by excessive limitation of diet. If they are lower than they ought to be in weight they must be made to regain it. Above all, there must be no limitation of meat-eating except in the robust. Very often the heart seems to crave particularly that form of nutrition that comes through meat. It is especially important that the bowels should be regular. Fast eating is very harmful. Occupation with serious business immediately after eating is almost the rule in these cases.

All of these elements of the case need special study in each individual patient. The needed suggestions can then be made. Above all, the patient is made to realize that his case is understood and that it is only the question of a gradual acquirement of certain habits, including proper exercise, that is needed for the restoration of his heart to normal.

CHAPTER V

ANGINA PECTORIS

The two forms of this affection, known commonly as true and false angina, are characterized by pain or anguish in the precordial region with reflected pains in other portions of the body. It used to be said that whenever the precordial pain was accompanied by reflected pains in the neck, or down the arm, or, as they may be occasionally, in the jaw, in the ovary, in the testicle, sometimes apparently in the left loin, this was true angina and the patient was in serious danger of death. We know now that false angina may be accompanied by various reflex pains and that, indeed, a detailed description of the anguish and its many points of manifestation is more likely to be given by a neurotic patient suffering from pseudo-angina than by one suffering from true angina. True angina occurs in most cases as a consequence of hardening of the arteries of the heart or of some valvular lesion that interferes in some way with cardiac nutrition. The definite sign of differentiation is that in practically all cases of true angina, there are signs of arterial degeneration in various parts of the body. Without these, the "breast pang," as the English call it, is likely to be neurotic and is of little significance as regards future health or its effect upon the individual's length of life.

Besides the physical pain that accompanies this affection there is, as was pointed out by Latham, a profound sense of impending death. It used to be said that this was characteristic of the organic lesions causing true angina pectoris. It is now well known, however, that the same feeling or such a good imitation of it that it is practically impossible to recognize the true from the false, occurs in pseudo-angina. It is this special element in these cases that needs most to be treated by psychotherapy and which, indeed, can only be reached in this way. Where there are no signs of arterial degeneration and no significant murmurs in the heart, it should be made clear to these patients that they are not suffering from a fatal disease, but only from a bothersome nervous manifestation. Especially can this reassurance be given if the angina occurs in connection with distention of the stomach or in association with gastric symptoms of any kind. In young patients who are run down in health and above all in young women, the subjective symptoms of angina—the physical anguish and the sense of impending death—are all without serious significance.

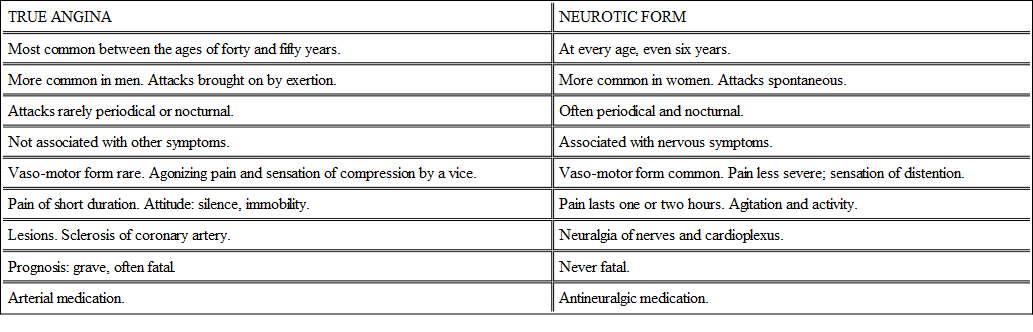

Differential Diagnosis of True and False Angina.—In the diagnosis of angina pectoris the main difficulty, of course, lies in the differentiation between the true and false forms, that is, those dependent on an organic affection of the heart muscle or blood vessels and those resulting from a neurosis. The neurotic form is not uncommon in young people and is often due to a toxic condition. Coffee is probably one of the most frequent causes of spurious angina, though the discomfort it produces is likely to be mild compared with the genuine heart pang. It must not be forgotten, however, that neurotic patients exaggerate their pains and describe their distress in the heart region as extremely severe and as producing a sense of impending death, when all they mean is that, because the pain is near their heart it produces an extreme solicitude and that a dread of death comes over them because of this anxiety. Coffee and tea, especially when taken strong and in the quantities in which they are sometimes indulged in, may be sources of similar distress. Tobacco will do the same thing in susceptible individuals, or where there is a family idiosyncrasy, and especially in young persons.

For the differentiation of true and spurious angina Huchard's table as given by Osler is valuable:

True Angina and Psychotherapy.—One of the most frequent occasions for the development of true angina is vehement emotion. The place of psychotherapy then in the affection will at once be recognized. A classical example of the influence of the mind and the emotions in the production of attacks of angina pectoris in those who are predisposed to them by a pre-existing pathological condition, is the case of the famous John Hunter. He was attacked by a fatal paroxysm of the affection in the board room of St. Thomas' Hospital, London, when he was about to begin an angry reply with regard to some matter concerning the medical regulation of the hospital. He had previously recognized how amenable he was to attacks of the disease as a consequence of emotion or excitement, and had even stated to friends that he was at the mercy of any scoundrel who threw him into an attack of anger. Some of the deaths from fright or sorrow at a sudden announcement of the death of a relative, or even the deaths from joy are due to angina pectoris precipitated by the serious strain put upon the heart by the flood of terror or emotion.

Men who are sufferers from what seems to be true angina pectoris must be made to understand without disturbing them any more than is absolutely necessary that strong emotions of any kind—worry, anger, exhibitions of temper, and, above all, family quarrels, must be avoided. Not a few of the serious attacks of angina pectoris which physicians see come as a consequence of family jars, owing to the persistence of a son or daughter in a course offensive to the parent. A part of the prophylaxis, then, consists in impressing this fact on members of the family and making them understand the danger. The disposition that causes the family friction is, however, often hereditary and will, therefore, prove difficult of control. It is one of the typical cases of inheritance of defeats.

Solicitude and Prognosis .—The distinguished French neurologist, Charcot, had several attacks of what seemed to be true angina pectoris. His friends were much disturbed by it. Physicians who saw him during the attack feared that he was suffering from an incurable heart lesion. He himself, as his son, Dr. Charcot, told me, refused to accept this diagnosis, and preferred to believe that what he was suffering from was a cardiac neurosis—and, of course, he had seen many of them. He was unwilling to have a heart specialist examine him very carefully for he did not wish to be persuaded of the worst aspects of his condition.

What he said in effect was, "This is either a neurotic condition, as I think it is, or it is an organic condition. If it is organic, my physicians would be apt to tell me that I must stop working so hard, and I am sure that if I should do that I would do myself more harm than good by having unoccupied time on my hands. I want to go on doing my work. If I am wrong some time I shall be carried off in one of these attacks. That will not be such a serious thing, for after all I must die some time and my expectancy of life cannot normally be very long. I prefer, then, to go on with my work and think the best, for it does not seem that I could do anything that would put off the inevitably fatal issue if I am to die a cardiac death." He was found dead one morning, but he had passed into the valley of death without being seriously disturbed and without any of the neurotic symptoms that so often develop in discouraged patients. Curiously enough, one of our most distinguished heart specialists in this country went through almost the same experience and preferred to live "the brief active life of the salmon rather than the long slow life of the tortoise."

The best possible factor in therapy is secured if patients can be brought to the state of mind of these distinguished physicians who calmly faced the future, refusing to disturb themselves or their work, because they feared that the worry that would come down upon them in inactivity would aggravate their disease. Where men are occupied with some not too exacting occupation, that takes most of their attention and at which they have been for years, it is best to leave them at it, though the harder demands of it must be modified. If they can be brought to persuade themselves, as did the two physicians—though probably only half-heartedly—that their affections may possibly be merely neurotic and not true angina, it will always be better for them. Death may come, and commonly will, suddenly, but, after one has lived a reasonably full life, that is rather a blessing (and not in disguise) than the terror which it is sometimes supposed to be.

Pseudo-Angina.—The neurotic form of angina is quite compatible, not only with continued good health but with long life, and even after a long series of attacks, some of them very disturbing in their apparent severity, there may be complete relief for years, or for the rest of life. Exaggeration of feeling due to concentration of attention plays a large role in these cases, and it is evident that the dread of something the matter with the heart connected with even a slight sense of discomfort may readily become so emphasized as to seem severe pain, though many people have similar feelings without making any complaint.

In spite of reassurances attacks of pseudo-angina are likely to worry both patient and physician. The only working rule is that in younger people discomfort in the heart region, even though it may be accompanied by some sympathetic pain in the arm or in the left side of the neck, is usually spurious angina. Broadbent goes so far as to say that this is true also in many older persons. His method of making the differentiation is interesting because so easy and practical that it deserves to be condensed here. The earlier attacks of true angina are practically always provoked by exertion, while spurious angina is especially liable to come on during repose. Any cardiac symptom or pain that can be walked off may be set down as functional and due to some outside disturbing influence, or to nervous irritability. When palpitation or irregular action of the heart, or intermission of the pulse, or pain in the cardiac region, or a sense of oppression follows certain meals at a given interval, or comes on at a certain hour during the night, there need be little hesitation in attributing the disturbance, whatever it may be, to indigestion in some of its forms. Nightmare from indigestion, Broadbent thought, is not a bad imitation of true angina.

In Broadbent's mind acute consciousness of any heart disturbance lays it in general under the suspicion of being neurotic in origin. He was talking to some of the best clinical practitioners in the world and some of the most careful observers of our generation, when, before the London Medical Society, he said: "The intermission of the pulse of which the patient is conscious and the irregularity of the heart's action—though this can be said with less confidence—which the patient feels very much, is usually temporary and not the effect of organic heart disease." This is particularly true, of course, in people of a neurotic character, and Broadbent went on to say that "speaking generally, angina pectoris in a woman is always spurious, and the more minute and protracted and eloquent the description of the pain, the more certain may one be of the conclusion."

I had the opportunity to follow the case of a young woman who had a series of attacks of angina pectoris some twenty years ago, so severe that a bad prognosis seemed surely justified, and though at times the attacks were rather alarming to herself and friends, nothing serious developed and for the past ten years, since she has gained considerably in weight, they have not bothered her at all. She used to be rather thin and delicate, trying to do a large amount of work and living largely on her nervous energy. At times of stress she was likely to suffer from pain in the precordia running down the left arm and accompanied by an intense sense of the possibility of fatal termination. With reasonably large doses of nux vomica, an increase in appetite came and a steadying of her heart that soon did away with these recurrent attacks. These came back later several times when she neglected her general condition, but there never were any objective symptoms that pointed to an organic lesion. After twenty years she is in excellent health, except for occasional attacks of a curious neurotic indigestion that sometimes produces cardiac disturbances. Of course, such cases are not uncommon in the experience of those who see many cardiac and nervous patients.

For the treatment of pseudo-angina, mental influence is all important. Of course, the conditions which predispose to the mechanical interference with heart action that occasions the discomfort, must be relieved as far as possible. The severity of the symptoms, however, are much more dependent on the patient's solicitude with regard to them, they are much more emphasized by worry about them, than by the physical factors which occasion them. Reassurance is the first step towards cure. After relief has been afforded from the severer attacks, the patient's solicitude as to the future must be allayed and the fact emphasized that there are many cases in which a number of attacks of cardiac discomfort simulating angina pectoris have been followed by complete relief and then by many years of undisturbed life. It is important to make patients understand that, in spite of the fact that their attacks occur during the course of digestion, as is not infrequently the case, this constitutes no reason for lessening the amount of food taken. Nearly always these attacks occur with special frequency among those who are under weight, and disappear rather promptly when there is a gain in weight. Solicitude with regard to the heart must be relieved wherever possible and then with the regaining of general health the heart attacks will disappear.

CHAPTER VI

TACHYCARDIA

Etymologically tachycardia means rapid heart. There are two forms of rapid heart, that which is constant and that which occurs in periodical attacks. It is for this latter that the term tachycardia has been more particularly used, though occasionally the adjective paroxysmal is attached to it to indicate the intermittent character of the affection. With regard to the persistent type of rapid heart something deserves to be said, however, because patients' minds are often seriously disturbed by them. Often it has existed for years, sometimes is known to be a family trait and probably has existed from childhood, yet the discovery of it may be delayed until some pathological condition develops, calling for the attendance of a physician who may be needlessly alarmed and in turn alarm his patient by his recognition of it. The cause for this persistent rapid pulse is not well known and is difficult to determine. Heredity, as has been suggested, sometimes plays an important role in it. Certain families have one or more members in each generation with rapid hearts. Whenever persistent rapid heart is a family trait the patient can be assured, as a rule, without hesitation, that the general prognosis of the case is that of the lives of the rest of the family. Usually the symptom seems to mean nothing as regards early mortality or any special tendency to morbidity.

Favorable Prognosis.—While a rapid pulse often and indeed usually has some serious significance, it must not be forgotten that it may be an individual peculiarity and be quite compatible with long life and hard work. One of the first patients that I saw as a physician had a pulse between ninety-six and one hundred. As there was a slight tendency to irregular heart action also, I was inclined to think that there must be some cardiac muscle trouble. There was apparently no valve lesion. He told me that a physician ten years before had noted his rapid pulse and had made many inquiries about it which rather seriously disturbed him. He had been an extremely healthy man during his fifty-five years of life and there seemed no reason to conclude, since his rapid pulse had been in existence for ten years, that it meant anything serious. He has now lived well beyond the age of seventy and still has a pulse always above ninety. Contrary to what might be thought, he is an extremely placid, unexcitable individual, who, under ordinary circumstances, will probably live for many years to come. He has no family history of tachycardia, though there is a history of rather nervous irritable hearts in other members for two generations.

An interesting case of this kind came under my observation about fifteen years ago in a clergyman whose pulse was never below ninety, and who on slight excitement, or after a rapid walk, or after a heavy meal, would have a pulse of 120. He knew that it was a family trait, his father having had it yet living to be past seventy. He gave a history of its having been recognized in his own person more than twenty years before. His general health, however, was excellent. He took long walks and, indeed, pedestrian excursions were his favorite exercise. He was able to go up flights of stairs rather rapidly without discomfort. He was the pastor in a tenement house district so he had plenty of opportunity for such exertion. Infections of any kind, colds and the like, disturbed his pulse very much, if the ordinary standard was taken, but it was not irregular and the increase in rapidity was probably only proportionate to the original height of the pulse in his case. After all, as the normal pulse of sixty to seventy rises to between ninety and one hundred even in a slight fever, it is not surprising if a pulse normally above ninety should rise fifty per cent. to one hundred and thirty-five under similar conditions. He is now well past sixty, after over thirty-five known years—and probably longer—of a pulse above ninety, yet he is in excellent general health and promises, barring accident, to live beyond seventy.