Полная версия:

Yeti

I learned more about the yeti during nine expeditions to Mount Everest in my search for the English climber George Mallory. I lived for a total of two years on that mountain. As a boy, I had heard stories about my Uncle Hunch who had made the very first climb of the mountain with his friend Mallory. I remember standing on the lawn outside Verlands House in Painswick, aged twelve, and looking up at Hunch: the legendary Howard Somervell (who was actually a cousin, not an uncle). By then he was a stout old man in his eighties, but with a youthful twinkle in his eye. He knew he was starting a hare in front of this young boy.

Somervell was a remarkable polymath: a double first at Cambridge, a talented artist (his pictures of Everest are still on the walls of the Alpine Club in London) and an accomplished musician (he transcribed the music he heard in Tibet into Western notation). He had worked as a surgeon during the Somme offensive in the First World War, and during that apocalyptic battle he had to operate in a field hospital with a mile-long queue of litters carrying the broken and dying youth of Britain. During a rest from surgery, he sat and watched a young soldier lying asleep on the grass. It slowly dawned on him that the boy was dead, and it seems that it was this particular trauma that prompted him to throw away a successful career as a London surgeon and become a medical missionary in India instead.

Before all that, he was one of the foremost Alpinists in England. He was invited to join the 1922 Mount Everest expedition and took part in the first serious attempt to climb the mountain with his friend Mallory, and his oxygen-free height record with fellow climber Edward Norton in 1924 stood for over fifty years. He even won an Olympic gold medal. He was one of the extraordinary Everesters, from the land of the yeti.

Of course, I was only interested in the amazing story he was telling me. ‘Norton and I had a last-ditch attempt to climb Mount Everest, and we got higher than any man had ever been before. I really couldn’t breathe properly and on the way down my throat blocked up completely. I sat down to die, but as one last try I pressed my chest hard [and here the old man pushed his chest to demonstrate to me] and up came the blockage. We got down safely. We met Mallory at the North Col on his way up. He said to me that he had forgotten his camera, and I lent him mine. So if my camera was ever found, you could prove that Mallory got to the top.’ It was a throwaway comment, which he probably made a hundred times in the course of telling this story, but this time it found its mark.

So I spent much of the rest of my life learning to be a mountaineer and then hunting for the camera on Mount Everest. This search would also lead me to the yeti. Many times, I cursed myself for chasing Uncle Hunch’s wild goose, but on the way we found George Mallory’s body. Poor Mallory. His shroud was the snow.8

CHAPTER TWO

When men and mountains meet … campfire stories … the Abdominal Snowman … the 1921 Reconnaissance of Mount Everest … a remarkable man … more footprints … The Valley of the Flowers.

‘Great things are done when men and mountains meet’ wrote William Blake. He might have added that there would be some great tales, too. On one Mallory filming expedition, I climbed with the actor Brian Blessed to around 25,000 feet on the North Ridge of Mount Everest. His generous stomach and his bellowing of stories around the campfire earned him the nickname of Abdominal Snowman. The Sherpas were fascinated by him and swore that he actually was a yeti. They would giggle explosively and roll on the snow with laughter at his antics. Sherpa people generally have a good sense of fun, and I noticed that whenever a yeti was mentioned this would often provoke a smile, a laugh – but occasionally an uneasy look.

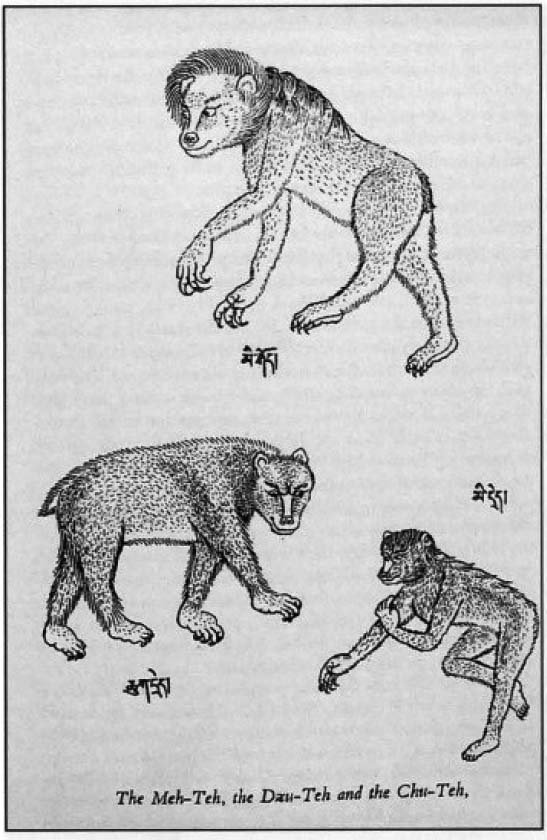

In the course of thirty or so trips to the Himalayas, I heard many tales about the beast from Sherpas and they were clearly believers. There are very similar stories from local villagers all along the Himalayas, from Arunachal Pradesh to Ladakh, and even though the names changed they seemed to be talking about three kinds of yeti. First, and largest, is the terrifying dzu-teh, who stands eight feet tall when he is on his back legs; however, he prefers to walk on all fours. He can kill a yak with one swipe of his claws. There is the smaller chu-the or thelma, a little reddish-coloured child-sized creature who walks on two legs and has long arms. He is seen in the forests of Sikkim and Nepal. Then there is the meh-teh, who is most like a man and has orangey-red fur on his body. He attacks humans and is the one most often depicted on monastery wall paintings. Yeh-teh or yeti is a mutation of his name. He looks most like the Tintin in Tibet yeti.

A drawing of the three yetis by Lama Kapa Kalden of Khumjung, 1954.

Some of the Sherpas I climbed with had stories about family yaks being attacked, and yak-herders terrorised by a creature that sounds like the enormous dzu-teh. In 1986 in Namche Bazaar, capital of the Sherpa Khumbu region, I met Sonam Hisha Sherpa. Twenty years previously, he had been grazing his yak/cow crosses, the dzo, high on a pasture. During the night, he heard loud whistling and bellowing while he cowered with fright in a cave with his companions. They were sure they were going to be killed by the dzu-teh after it had finished with their livestock. In the morning, Sonam and his men found that two dzo had been killed and eaten. There was no meat or bones remaining: only blood, dung and intestines.

So what was the truth about the yeti? After my own Bhutanese yeti finding, I decided to follow the footprints back in recorded history and see what stood up to scrutiny. In this book, we’ll follow the Westerners’ yeti tracks first and see if they lead us to the original Himalayan yeti. On the way, we will meet some of the most remarkable men in exploration history.

The earliest Western account of a wild man in the Himalayas dates from 1832 and is given by Brian Houghton Hodgson, the Court of Nepal’s first British Resident, and the first Englishman permitted to visit this forbidden land. Hodgson had to contend with the hotbed that was (and still is) Nepalese politics. He was particularly interested in the natural history and ethnography of the region, and so his report carries some weight. He recorded that his native hunters had been frightened by a ‘wild man’:1

Religion has introduced the Bandar [rhesus macaque] monkey into the central region, where it seems to flourish, half domesticated, in the neighbourhood of temples, in the populous valley of Nepal proper [this is still the case]. My shooters were once alarmed in the Kachár by the apparition of a ‘wild man’, possibly an ourang, but I doubt their accuracy. They mistook the creature for a càcodemon or rakshas (demons), and fled from it instead of shooting it. It moved, they said, erectly, was covered with long dark hair, and had no tail.

It has to be noted that Hodgson didn’t see the wild man of Nepal himself, and he doubted the story. We can go back further in history for stories about wild men. Alexander the Great set out to conquer Persia and India in 326 BC, penetrating nearly as far as Kashmir. He heard about strange wild men of the snows, who were described as something like the satyrs, the lustful Greek gods with the body of a man but the horns, legs and feet of an animal. Alexander demanded to have one of them brought to him, but the local villagers said the creature could not survive at low altitude (rather a good excuse). Later, Pliny the Elder wrote in his Naturalis Historia: ‘In the land of the satyrs, in the mountains that lie to the east of India, live creatures that are extremely swift, as they can run on both four feet and on two. They have bodies like men, and because of their speed can only be caught when they are ill or old.’ He went on to describe monstrous races of peoples such as the cynocephali or dog-heads, the sciapodae, whose single foot was so huge it could act as a sunshade, and the mouthless astomi, who lived on scents alone. By comparison, his yeti sounds quite plausible. ‘When I have observed nature she has always induced me to deem no statement about her incredible.’

Septimius Severus was the only Roman emperor to be born in Libya, Africa, and he lived in York between 208 and 211 BC. His head priest, Claudius Aelianus, wrote De Natura Animalium (On the Nature of Animals), a book of facts and fables about the animal kingdom designed to illustrate human morals. I like to imagine the Roman emperor reading it to take his mind off his final illness during the Yorkshire drizzle. In his book, Aelianus describes an animal similar to the yeti:

If one enters the mountains of neighbouring India, one comes upon lush, overgrown valleys … animals that look like Satyrs roam these valleys. They are covered with shaggy hair and have a long horse’s tail. When left to themselves, they stay in the forest and eat tree sprouts. But when they hear the dim of approaching hunters and the barking of dogs, they run with incredible speed to hide in mountain caves. For they are masters at mountain climbing. They also repel approaching humans by hurling stones down at them.

The first sighting of yeti footprints by a Westerner was made by the English soldier and explorer Major Laurence Waddell. He was a Professor of Tibetan Culture and a Professor of Chemistry, a surgeon and an archaeologist, and he had roamed Tibet in disguise. He is thought by some to be the real-life precursor of the film character Indiana Jones.2 One of his theories included a belief that the beginning of all civilisation dated from the Aryan Sumerians who were blond Nordics with blue eyes. These theories were later picked up by the German Nazis and led to their expedition to Tibet in 1938–39. While exploring in northeast Sikkim in 1889, Waddell’s party came across a set of large footprints which his servants said were made by the yeti, a beast that was highly dangerous and fed on humans:

Some large footprints in the snow led across our track and away up to the higher peaks. These were alleged to be the trail of the hairy wild men who are believed to live amongst the eternal snows, along with the mythical white lions, whose roar is reputed to be heard during storms [perhaps these were avalanches]. The belief in these creatures is universal amongst Tibetans. None, however, of the many Tibetans who I have interrogated on this subject could ever give me an authentic case. On the most superficial investigation, it always resolved into something heard tell of. These so-called hairy wild men are evidently the great yellow snow-bear (Ursus isabellinus) which is highly carnivorous and often kills yaks. Yet, although most of the Tibetans know this bear sufficiently to give it a wide berth, they live in such an atmosphere of superstition that they are always ready to find extraordinary and supernatural explanations of uncommon events.3

Note that Major Waddell did not believe in the story of wild men, and identified the creature as a bear. It should also be noted that Ursus isabellinus comes in many colours: sometimes yellow, sometimes sandy, brown or blackish. Crucially for our story, Waddell was the first modern European to report the existence of the yeti legend. In so doing, he was the first in a long line of British explorers whose words on the yeti were misrepresented and whose conclusions were deleted.

The next explorer to march across our stage is Lt-Col. Charles Howard-Bury, leader of the 1921 Everest reconnaissance expedition, who saw something strange when he was crossing the Lhakpa’ La at 21,000 feet.

Howard-Bury was another of the extraordinary Everesters. He was wealthy and moved easily in high society. He had a most colourful life, growing up in a haunted gothic castle at Charleville, County Offaly, Ireland. Then, in 1905, he stained his skin with walnut juice and travelled into Tibet without permission, being ticked off by the viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, on his return (Tibet must have been crowded with heavily stained Englishmen at that time). He bought a bear cub, named it Agu and took it home to Ireland where it grew into a seven-foot adult. So he was familiar with bear prints. He was taken prisoner during the First World War by the Germans and staged an escape with other officers. He never married and lived with the Shakespearean actor Rex Beaumont, whom he had met, aged 57, when Beaumont was 26. Together they restored Belvedere House, Westmeath, Ireland, and also built a villa in Tunis. Here they entertained colourful notables such as Sacheverell Sitwell, Dame Freya Stark and the professional pederast André Gide.

Was Howard-Bury prone to the telling of tall stories? Fellow Everester George Mallory didn’t much like him but thought not. The story he brought back seemed entirely plausible to fellow members of the Alpine Club. He was a careful observer of nature and a plant hunter (Primula buryana is named after him). After the Mallory research, I found it hard to disentangle truth from wishful thinking, but I felt that it was important to note what Howard-Bury himself observed and then see how the newspapers reported the story. Howard-Bury’s diary notes for 22 September 1921 read: ‘We distinguished hare and fox tracks; but one mark, like that of a human foot, was most puzzling. The coolies assured me that it was the track of a wild, hairy man, and that these men were occasionally to be found in the wildest and most inaccessible mountains.’

Later, he expanded the story: he reported that the party (including Mallory, who also saw the tracks) was camped at 20,000 feet and set off at 4am in bright moonlight to make their crossing of the pass. On the way, they saw the footprints, which ‘were probably caused by a large loping grey wolf, which in the soft snow formed double tracks rather like those of a bare-footed man’. However, the porters ‘at once volunteered that the tracks must be that of “The Wild Man of the Snows”, to which they gave the name metoh kangmi’.

Howard-Bury himself did not believe these stories. He had sent a newspaper article home by telegraph, and, as Bill Tilman so delightfully put it in his famous yeti Appendix B to Mount Everest 1938: ‘In order to dissociate himself from such an extravagant and laughable belief he put no less than three exclamation marks after the statement (the Wild Men of the Snows!!!); but the telegraph system makes no allowance for subtleties and the finer points of literature, the savings sign were omitted, and the news was accorded very full value at home.’4

The Times of London ran the story under the lurid headline of ‘Tibetan Tales of Hairy Murderers’. As a result, a journalist for The Statesman in Calcutta, Henry Newman, who wrote under the telling pseudonym ‘Kim’, interviewed the porters on their return to Darjeeling. It is rare that you can spot the actual beginning of a legend, but here is the moment of birth of the Western yeti:

I fell into conversation with some of the porters, and to my surprise and delight another Tibetan who was present gave me a full description of the wild men, how their feet were turned backwards to enable them to climb easily and how their hair was so long and matted that, when going downhill, it fell over their eyes … When I asked him what name was applied to these men, he said ‘metoh kangmi’: kangmi means ‘snow men’ and the word ‘metoh’ I translated as ‘abominable’.

This was a mis-translation. Howard-Bury had already offered ‘man-bear’ as the translation. Later we will see that what ‘another Tibetan’ probably said was meh-teh, which was a fabled creature familiar to any Sherpa or Tibetan who had heard the stories on his mother’s knee, or who had looked up at the frescoes in a Buddhist monastery. What the porters were describing was perfectly familiar to them in their own terms: ‘man-bear’. Tilman recounted in his Appendix B how Newman wrote a letter long afterwards in The Times, a paper with a long and profitable relationship with the Abominable Snowman and Mount Everest. ‘The whole story seemed such a joyous creation, that I sent it to one or two newspapers. Later I was told I had not quite got the force of the word “metch”, which did not mean “abominable” quite so much as filthy or disgusting, somebody wearing filthy tattered clothing. The Tibetan word means something like that, but it is much more emphatic, just as a Tibetan is more dirty than anyone else.’

In fact, Newman, Tilman or his publisher had got the spelling wrong: the letters TCH cannot be rendered in Tibetan, and what Newman probably should have written was ‘metoh’, meaning man-bear and certainly not ‘abominable’. The word that the Sherpas use to refer to the creature is actually yeh-teh, or yeti, which is perhaps a corruption of meh-teh, again ‘man-bear’.

It may seem that I am making a meal of this, but whether by accident or by design Newman had ‘improved’ the story to invent a name that was not a true translation of what the porters had actually said, but instead was destined to send a frisson of horror through The Times readers of the Home Counties. This was such a powerful new myth that it may have helped the eventual climbing of Mount Everest.

Newman had gleaned the fascinating fact that the wild men had their feet turned backwards to enable them to climb easily, which is an odd detail as climbers in those pre-war days used to reverse up very steep ice slopes when wearing their flexible crampons. Newman’s pseudonym ‘Kim’ suggests that he was an admirer of Rudyard Kipling’s character, the boy-spy, and so the Western yeti also began his long and peculiar association with the intelligence services, eventually reaching as far as MI5 and the CIA. As for Newman’s exaggeration of the name Abominable Snowman, perhaps he was gilding a dog’s ear, but whatever his reason the name stuck.

Thus began the long-running Western legend of the Abominable Snowman/yeti. And all because of the absence of three exclamation marks!!! Another newspaper picked up the first report and embellished it in January 1922, claiming that Howard-Bury’s party had discovered ‘a race of wild men living among the perpetual snows’. There was a quote from one William Hugh Knight, who the writer claimed was ‘one of the best known explorers of Tibet’, and a member of ‘the British Royal Societies club’ who said that he had ‘seen one of the wild men from a fairly close distance sometime previously; he hadn’t reported it before, but felt that due to the statement about manlike footprints that was made by Howard-Bury’s party, he was now compelled to add his own evidence to the growing pile’.

Knight said that the wild man was ‘… a little under six feet high, almost stark naked in that bitter cold: it was the month of November. He was kind of pale yellow all over, about the colour of a Chinaman, a shock of matted hair on his head, little hair on his face, highly-splayed feet, and large, formidable hands. His muscular development in the arms, thighs, legs, back, and chest was terrific. He had in his hand what seemed to be some form of primitive bow.’ The article went on to claim that the porters had seen the creatures moving around on the snow slopes above them.

The only problem is that William Hugh Knight wasn’t one of the best-known explorers of Tibet, and the British Royal Societies club didn’t exist. However, there was a Captain William Henry Knight, who had obtained six months’ leave to explore Kashmir and Ladakh over sixty years earlier, in 1860, and wrote the Diary of a Pedestrian in Cashmere and Thibet,5 but nothing in his book resembles the reported description. It would seem that the journalist had plucked the name of a long-dead real Tibetan explorer, changed the name slightly, invented an explorer’s club and made up the quote.6 This was indeed part of a growing pile: a pile of lies. Incidentally, note that at this stage the wild man is recognisably human: he is partly clothed, he has little hair on his face and he carries a bow. It is only later that he becomes more like the furry ape of legend.

Howard-Bury was well aware of the sensation his report had caused. In his book about the expedition, Mount Everest: The Reconnaissance, 1921, he wrote: ‘We were able to pick out tracks of hares and foxes, but one that at first looked like a human foot puzzled us considerably. Our coolies at once jumped to the conclusion that this must be “The Wild Man of the Snows”, to which they gave the name of metoh kangmi, “the abominable snowman” who interested the newspapers so much. On my return to civilised countries I read with interest delightful accounts of the ways and customs of this wild man who we were supposed to have met.’7

What was needed now, of course, was a sighting, and so along it came. In 1925 the British-Greek photographer N. A. Tombazi was on a British Geological Expedition near the Zemu glacier, when he spotted a yeti-like figure between 200 and 300 yards away. He reported: ‘Unquestionably, the figure in outline was exactly like a human being, walking upright and stopping occasionally to uproot or pull at some dwarf rhododendron bushes. It showed up dark against the snow and as far as I could make out, wore no clothes. Within the next minute or so it had moved into some thick scrub and was lost to view.’

Later, Tombazi and his companions descended to the spot and saw footprints ‘similar in shape to those of a man, but only six to seven inches long by four inches wide … The prints were undoubtedly those of a biped.’8 Tombazi did not believe in the Abominable Snowman and thought what he had seen was a wandering pilgrim. One wonders why he bothered to report the sighting at all, but this suggests that thoughts of mysterious bipedal beasts were beginning to enter the minds of Himalayan explorers.

Undaunted by this conclusion, writers of books about Mount Everest, fuelled by George Mallory and Andrew Irvine’s mysterious disappearance near the summit in 1924, embroidered the tale even further. In 1937, Stanley Snaith produced a pot-boiler, At Grips with Everest, covering the five Everest expeditions to date, filled with speech-day guff about how Everest was ‘spiritually within our Empire’. He described how the Abominable Snowman’s footprints were made by ‘a naked foot: large, splayed, a mark where the toes had gripped the ground where the heel had rested.’9 This is not what Howard-Bury reported, but from then on these tracks were made by a man-like monster.

The Case of the Abominable Snowman was a whodunit written in 1941 by one of our poets laureate, Cecil Day-Lewis, using the pen-name Nicholas Blake. Although not featuring the yeti but instead a corpse discovered inside a melting snowman, it indicated that the term had entered the public mind.

Our next book which exaggerated and distorted the Howard-Bury and Waddell reports was Abominable Snowmen by Ivan T. Sanderson. According to Sanderson, in 1920 (the wrong date) the Everest team led by Howard-Bury were under the Lhapka-La [sic] at 17,000 feet (the wrong altitude) watching ‘a number of dark forms moving about on a snowfield far above’. (They didn’t.) They hastened upwards and found footprints a size ‘three times those of normal humans’. (No!) Ivan T. Sanderson then states that the porters used the term yeti (and no, they didn’t).