Полная версия:

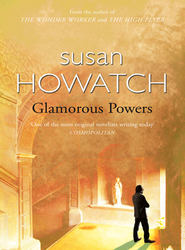

Glamorous Powers

It would have been hard to imagine a superior less capable of dealing with my vision.

III

My antipathy to Francis was undoubtedly the main reason why I did not confide in him as soon as I had received my vision, but possibly I would have been almost as hesitant to confide in Cyril or Aidan. For twenty-four hours after the vision I was in shock. I believed I had received a call from God to leave the Order, and this belief at first triggered a purely emotional response: I felt an elated gratitude that God should have revealed His will to me in such a miraculous manner, and as I offered up my thanks with as much humility as I could muster I could only pray that I would be granted the grace to respond wholeheartedly to my new call.

However eventually this earthquake of emotion subsided and my intellect awoke. Reason tried to walk hand in hand with revelation and the result was disturbing. My first cold clear thought was that the vision was connected with my failure to become Abbot-General; it could be argued that since the Order, personified by Father Darcy, had rejected me I was now rejecting the Order, a rejection which, because it had been suppressed by my conscious mind, had manifested itself in a psychic disturbance.

This most unsavoury possibility suggested that I might have fallen into a state of spiritual debility, and as soon as I started to worry about my spiritual health I remembered that I was due to make my weekly confession on the morrow.

My confessor was Timothy, the oldest monk in the house, a devout man of eighty-two who possessed an innocent happiness which made him much loved in the community. After my installation as Abbot I had picked him to be my confessor not merely because he was the senior monk but because I knew he would never demand to know more than I was prepared to reveal. This statement may sound distressingly cynical, but I had been brought to Grantchester to bring a lax community to order and since in the circumstances it would have been inadvisable for me to display weakness to anyone, even the holiest of confessors, I had decided that the temptation to set down in the confessional the burden of my isolation should be resisted.

As I now contemplated my duty to set down the burden represented by my vision I knew that the most sensible solution was to circumvent Timothy by journeying to London to lay the problem before my superior. But still I balked at facing Francis. Could I make confession without mentioning the vision? Possibly. It was the easiest solution. But easy solutions so often came from the Devil. I decided to pray for guidance but as soon as I sank to my knees I remembered my mentor and knew what I should do. Father Darcy would have warned me against spiritual arrogance, and with profound reluctance I resigned myself to being at least partially frank with my confessor.

IV

‘… and this powerful light shone through the north window. As the light increased in brilliance I knelt down, covering my face with my hands, and at that moment I knew –’ I broke off.

Timothy waited, creased old face enrapt, faded eyes moist with excitement.

‘– I knew the vision was ending,’ I said abruptly. ‘Opening my eyes I found myself back in my cell.’

Timothy looked disappointed but he said in a hushed voice, much as a layman might have murmured after some peculiarly rewarding visit to the cinema: ‘That was beautiful, Father. Beautiful.’

Mastering my guilt that I had failed to be honest with him I forced myself to say: ‘It’s hard to venture an opinion, I know, but I was wondering if there could be some connection between the vision and the death of Father Abbot-General last month.’

Since he knew nothing of Father Darcy’s deathbed drama I fully expected a nonplussed reaction, but to my surprise Timothy behaved as if I had shown a brilliant intuitive insight. ‘That hadn’t occurred to me, Father,’ he confessed, ‘but yes, that makes perfect sense. Father Abbot-General – Father Cuthbert, as I suppose we must now call him – was so good to you always, taking such a special interest in your spiritual welfare, and therefore it’s only natural that you should have been severely affected by his death. But now God’s sent you this vision to help you overcome your bereavement and continue with renewed faith along your spiritual way.’

‘Ah.’ I was still wondering how I could best extricate myself from this morass of deception when Timothy again surprised me, this time by embarking on an interpretation which was both intriguing and complex.

‘The chapel was a symbol, Father,’ he said. ‘It represents your life in the Order, while the mysterious bag beneath the trees represents your past life in the world, packed up and left behind. And your journey through the chapel was an allegory. You opened the door; that represents your admittance to the Order as a postulant. You crossed the bleak empty space where there were no pews; that signifies those difficult early months when you began your monastic life here in Grantchester.’ Timothy, of course, could remember me clearly as a troubled postulant; one of the most difficult aspects of my return to Grantchester had been that there were other monks less charitable than Timothy who took a dim view of being ruled by a man whom they could remember only as a cenobitic disaster. ‘But you crossed the empty space,’ Timothy was saying tranquilly, ‘and you reached the pews; they represent our house in Yorkshire where you found contentment at last, and the lilies placed beneath the memorial tablet symbolize the flowering of your vocation. Your walk down the central aisle must represent your progress as you rose to become Master of Novices, and the bright light at the end must symbolize the bolt from the blue – your call to be the Abbot here at Grantchester. But of course the light was also the light of God, sanctifying your vision, blessing your present work and reassuring you that even without Father Cuthbert’s guidance you’ll be granted the grace to serve God devoutly in the future.’ And Timothy crossed himself with reverence.

It was a plausible theory. The only trouble was I had no doubt it was quite wrong.

V

Having revealed my most urgent problem in this disgracefully inadequate fashion, I then embarked on the task of confessing my sins. ‘Number one: anger,’ I said briskly. My confessions to Timothy often tended to resemble a list dictated by a businessman to his secretary. ‘I was too severe with Augustine when he fell asleep in choir again, and I was also too severe with Denys for raiding the larder after the night office. I should have been more patient, more forgiving.’

‘It’s very difficult for an abbot when he doesn’t receive the proper support from all members of his community,’ said Timothy. He was such a good, kind old man, not only in sympathizing with me but in refraining to add that our community had more than its fair share of drones like Augustine and Denys. My predecessor Abbot James had suffered from a chronic inability to say no with the result that he had admitted to the Order men who should never have become professed. The majority of these had departed when they discovered that the monastic life was far from being the sinecure of their dreams, but a hard core had lingered on to become increasingly useless, and it was this hard core which was currently, in my disturbed state, driving me to distraction.

Having mentally ticked ‘anger’ off my list I confessed to the sin of sloth. ‘I find my work a great effort at the moment,’ I said, ‘and I’m often tempted to remain in my cell – not to pray but to be idle.’

‘Your life’s very difficult at present,’ said Timothy, gentleness unremitting. ‘You have to deal with the young men who knock on our door in the hope that they can evade military service by becoming monks, and then – worse still – you have to deal with our promising young monks who feel called to return to the world to fight.’

‘I admit I was upset to lose Barnabas, but I must accept the loss, mustn’t I? If a monk wishes to leave the Order,’ I said, ‘and if his superior decides the wish is in response to a genuine call, that superior has no right either to stop him or to feel depressed afterwards.’

‘True, Father, but what a strain the superior has to endure! It’s not surprising that you should be feeling a little dejected and weary at present, particularly in view of Father Cuthbert’s recent death, and in consequence you must now be careful not to drive yourself too hard. You have a religious duty to conserve your energy, Father. Otherwise if you continue to exhaust yourself you may make some unwise decisions.’

I recognized the presence of the Spirit. I was being told my vision needed further meditation and that I was on no account to make a hasty move. Feeling greatly relieved I crossed ‘sloth’ off my list and rattled off a number of minor sins before declaring my confession to be complete, but unfortunately this declaration represented yet another evasion for my two most disturbing errors of the past week had been omitted from my list. The first error consisted of my uncharitable behaviour during a disastrous quarrel with my son Martin, and the second error consisted of my unmentionable response to the unwelcome attentions of a certain Mrs Ashworth.

VI

After making this far from satisfactory confession to Timothy I retired to the chapel to complete my confession before God. Later as I knelt praying I became aware of Martin’s unhappiness, a darkness soaked in pain, and as I realized he was thinking of me I withdrew to my cell to write to him.

‘My dear Martin,’ I began after a prolonged hesitation, ‘I trust that by now you’ve received the letter which I wrote immediately after our quarrel last Thursday. Now that four days have elapsed I can see what a muddled inadequate letter it was, full of what I wanted (your forgiveness for my lack of compassion) and not enough about your own needs which are so much more important than mine. Let me repeat how ashamed I am that I responded so poorly to the compliment you paid me when you took me into your confidence, and let me now beg you to reply to this letter even if this means you must tell me how angry and hurt you were by my lack of understanding. I know you wouldn’t want me to “talk religion” to you, but of course you’re very much in my thoughts at present and I pray daily that we may soon be reconciled. I remain as always your devoted father, J.D.’

Having delivered myself of this attempt to demonstrate my repentance I was for some hours diverted from my private thoughts by community matters, but late that night I again sat down at the table in my cell and embarked on the difficult task of writing to Mrs Ashworth.

‘My dear Lyle,’ I began after three false starts. I had been accustomed to address her by her first name ever since I had once counselled her in an emergency, but now I found the informality grated on me. ‘Thank you so much for bringing the cake last Thursday afternoon. In these days of increasing shortages it was very well received in the refectory.

‘Now a word about your worries. Is it possible, do you think, that your present melancholy is associated in some way with Michael’s birth? I seem to remember that you suffered a similar lowering of the spirits after Charley was born in 1938, and indeed I believe such post-natal difficulties are not uncommon. Do go to your doctor and ask if there’s anything he can do to improve your physical health. The mind and the body are so closely linked that any physical impairment, however small, can have a draining effect on one’s psyche.

‘I’m afraid it’s useless to ask me to heal you, as if I were a magician who could wave a magic wand and achieve a miracle. The charism of healing is one which for various reasons I avoid exercising except occasionally during my work as a spiritual counsellor, and as you know, I never counsel women except in emergencies. This is not because I wish to be uncharitable but because a difference in sex raises certain difficulties, as any modern psychiatrist will tell you, and these difficulties often create more problems than they solve. May I urge you again to consult Dame Veronica at the convent in Dunton? I know your aversion to nuns, but let me repeat that Dame Veronica is the best kind of counsellor, mature, sympathetic, intuitive and wise, and I’m sure she would listen with understanding to your problems.

‘Meanwhile please never doubt that I shall be praying regularly for you, for Charles and for the children in the hope that God will bless you and keep you safe in these difficult times which at present engulf us all.’

Having thus extricated myself (or so I hoped) from Mrs Ashworth’s far from welcome attentions I then wasted several minutes trying to decide how I should sign the letter. The Fordites, though following a Benedictine way of life, are Anglo-Catholics anxious to draw a firm line between themselves and their Roman brethren so the use of the traditional title ‘Dom’ is not encouraged. Usually I avoided any pretentious signature involving the word ‘Abbot’ and a string of initials which represented the name of the Order, but sometimes it was politic to be formal and I had a strong inclination to be formal now. However the danger of a formal signature was that Lyle Ashworth might consider it as evidence that I was rejecting her, and I was most anxious that in her disturbed state I should do nothing which might upset her further. An informal signature, on the other hand, might well be even more dangerous; if I had been writing to her husband I would have signed myself JON DARROW without a second thought, but I could not help feeling that a woman like Lyle might find an abbreviated Christian name delectably intimate.

I continued to hesitate as I reflected on my name. Before entering the Order I had chosen to be Jon but abbreviated names were not permitted to novices so I found I had become Jonathan. Yet so strong was my antipathy to this name that later, as I approached my final vows, I had requested permission to assume the name John – the cenobitic tradition of choosing a new name to mark the beginning of a new life was popular though not compulsory among the Fordites – and I had been greatly disappointed when this request had been refused. I suspected Father Darcy had decided that any pampering, no matter how mild, would have been bad for me. It was not until some years later when I became Ruydale’s Master of Novices that I was able to take advantage of the fact that shortened names were not forbidden in private among the officers, and a select group of my friends was then invited to use the abbreviation.

As time went on I also dropped the name Jonathan when introducing myself to those outside the Order who sought my spiritual direction, and now I had reached the point where I considered the name part of a formal ‘persona’, like the title Abbot, which had been grafted on to my true identity as a priest. I thought of Lyle Ashworth again, and the more I thought of her the more convinced I became that this was a case where Jon the priest should disappear behind Jonathan the Abbot, even though I had no wish to upset her by appearing too formal. I sighed. Then shifting uneasily in my chair I at last terminated this most troublesome epistolary exercise by omitting the trappings of my title but nevertheless signing myself austerely JONATHAN DARROW.

VII

Neither Lyle nor Martin replied to my letters but when Dame Veronica wrote to say that Lyle had visited her I realized with relief that my counsel had not been ineffective. However I continued to hear nothing from Martin and soon my anguish, blunting my psyche, was casting a stifling hand over my life of prayer.

By this time I had exhaustively analysed my vision and reached an impasse. I still believed I had received a communication from God but I knew that any superior would have been justifiably sceptical while Francis Ingram would have been downright contemptuous. It is the policy of the religious orders of both the Roman and the Anglican Churches to treat any so-called vision from God as a delusion until proved otherwise, and although I was a genuine psychic this fact was now a disadvantage. A ‘normal’ man who had a vision out of the blue would have been more convincing to the authorities than a psychic who might be subconsciously manipulating his gift to reflect the hidden desires of his own ego.

I wrote yet again to Martin and this time, when he failed to reply, I felt so bitter that I knew I had to have help. I could no longer disguise from myself the fact that I was in an emotional and spiritual muddle and suddenly I longed for Aidan, the Abbot of Ruydale, who had looked after me with such wily spiritual dexterity in the past. As soon as I recognized this longing I knew I had to see him face to face; I was beyond mere epistolary counselling, but no Fordite monk, not even an abbot, can leave his cloister without the permission of his superior, and that brought me face to face again with Francis Ingram.

Pulling myself together I fixed my mind on how comforting it would be to confide in Aidan, and embarked on the letter I could no longer avoid.

‘My dear Father,’ I wrote, and paused. I was thinking how peculiarly repellent it was to be obliged to address an exact contemporary as ‘Father’ and absolutely repellent it was to be obliged to address Francis as a superior. However such thoughts were unprofitable. Remembering Aidan again I made a new effort to concentrate. ‘Forgive me for troubling you,’ I continued rapidly, ‘but I wonder if you’d be kind enough to grant me leave to make a brief visit to Ruydale. I’m currently worried about my son, and since Aidan’s met him I feel his advice would be useful. Of course I wouldn’t dream of bothering you with what I’m sure you would rank as a very minor matter, but if you could possibly sanction a couple of days’ absence I’d be most grateful.’ I concluded with the appropriate formula of blessings and signed myself JONATHAN.

He replied by return of post. My heart sank as I saw his flamboyant handwriting on the envelope, and I knew in a moment of foreknowledge that my request had been refused. Tearing open the letter I read:

‘My dear Jonathan, Thank you so much for your courteous and considerate letter. But I wonder if – out of sheer goodness of heart, of course – you’re being just a little too courteous and a little too considerate? If you have the kind of problem which would drive you to abandon your brethren and travel nearly two hundred miles to seek help, I suggest you journey not to Ruydale but to London to see me. I shall expect you next week on Monday, the seventeenth of June. Assuring you, my dear Jonathan, of my regular and earnest prayers …’

I crumpled the letter into a ball and sat looking at it. Then gradually as my anger triggered the gunfire of memory the present receded and I began to journey through the past to my first meeting with Francis Ingram.

VIII

I first saw Francis when we were freshmen at Cambridge. He was leading a greyhound on a leash and smoking a Turkish cigarette. He was also slightly drunk. During that far-off decade which concluded the nineteenth century Francis looked like a degenerate in a Beardsley drawing and talked like a character in a Wilde play. In response to my fascinated inquiry the college porter told me that this exotic incarnation of the spirit of the age was the younger son of the Marquis of Hindhead. The porter spoke reverently. Even in those early days of our Varsity career Francis was acclaimed as ‘a character’.

I wanted to be ‘a character’ myself, but I was up at Cambridge on a scholarship, my allowance was meagre and I knew none of the right people. Francis, I heard, gave smart little luncheon parties in his rooms and offered his guests caviar and champagne. Barely able to afford even the occasional pint of ale I nursed my jealousy in solitude and spent the whole of my first term wondering how I could ‘get on’.

‘If you get on as you should,’ my mother had said to me long ago, ‘then no one will look down on you because I was once in service.’

I was just thinking in despair that I was doomed to remain a social outcast in that bewitching but cruelly privileged environment when Francis noticed me. I heard him say to the porter as I drew back out of sight on the stairs: ‘Who’s that excessively tall article who looks like a bespectacled lamp-post and wears those perfectly ghastly cheap suits?’ And later he said to me with a benign condescension: ‘The porter mentioned that you told his fortune better than any old fraud in a fair-ground, and it occurred to me that you might be rather amusing.’

I received an invitation to his next smart little luncheon-party and put myself severely in debt by buying a new suit. The fortune-telling was a success. More invitations followed. Soon I became an object of curiosity, then of respect and finally of fascination; I had discovered that by devoting my psychic gifts to the furtherance of my ambition the closed doors were opening and I had become ‘a character’ at last.

‘Darrow’s the most amazing chap,’ said Francis to his latest ‘chère amie’. ‘He reads palms, stops watches without touching them and makes the table waltz around the room during a seance – and now he’s taken to healing! He makes his hands tingle, strokes you in the right place and the next moment you’re resurrected from the dead! He’s got this droll idea that he should be a clergyman but personally I think he was born to be a Harley Street quack – he’d soon have all society beating a path to his door.’

By that time we were in our final year and I was more ambitious than ever. It was true that I was reading theology out of a genuine interest to learn what the best minds of the past had thought about the God I already considered I knew intimately, but I was also possessed by the desire to ‘get on’ in the Church and I saw an ecclesiastical career as my best chance of self-aggrandisement; I used to dream of an episcopal palace, a seat in the House of Lords and invitations to Windsor Castle. Naturally I had enough sense to keep these worldly thoughts to myself, but an ambitious man exudes an unmistakable aura and no doubt those responsible for my moral welfare were concerned about me. Various members of the divinity faculty endeavoured to give me the necessary spiritual direction, but I was uninterested in being directed because I was fully confident that I could direct myself. I felt I could communicate with God merely by flicking the right switches in my psyche, but it was a regrettable fact that my interest in God faded as my self-esteem, fuelled by my social success, burgeoned to intoxicating new dimensions.

‘How divinely wonderful to see you – I’m in desperate need of a magic healer!’ said Francis’ new ‘chère amie’ when I arrived to ‘dine and sleep’ one weekend at her very grand country house. A widowed twenty-year-old, she had already acquired a ‘fin de siècle’ desire to celebrate her new freedom with as much energy as discretion permitted. ‘Dear Mr Darrow, I have this simply too, too tiresome pain in this simply too, too awkward place …’

I was punting idly with the lady on the Cam two days later when Francis approached me in another punt with two henchmen and tried to ram me. I managed to deflect the full force of the assault but when he tried to use the punting pole as a bayonet I lost my temper. Abandoning the lady, who was feigning hysterics and enjoying herself immensely, I leapt aboard Francis’ punt and tried to wrest the pole from him with the result that we both plunged into the river.

‘You charlatan!’ he yelled at me as we emerged dripping on the bank. ‘You common swinish rotter! You ought to be castrated like Peter Abelard and then burnt at the stake for bloody sorcery!’

I told him it was hardly my fault if he was too effete to satisfy the opposite sex, and after that it took five men to separate us. I remember being startled by his pugnacity. Perhaps it was then that I first realized there was very much more to Francis Ingram than was allowed to meet the eye.