Полная версия:

Year of the Tiger

Table of Contents

Title Page

Publisher’s Note

Map

London—1995

Chapter 1

Tibet—1959

Chapter 2

London—1962

Chapter 3

India—Tibet 1962

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

London—1995

Chapter 19

About the Author

Also by Jack Higgins

Copyright

About the Publisher

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

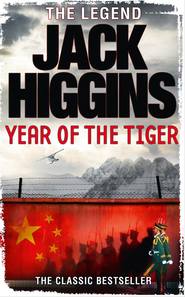

YEAR OF THE TIGER was first published by Abelard Shulman in 1963 under the name of Martin Fallon. The book went out of print very shortly after first publication, was never reprinted and never appeared in paperback.

The author was in fact Jack Higgins, Martin Fallon being one of the pseudonyms he used during his early writing days.

This edition of YEAR OF THE TIGER was revised and updated by Jack Higgins in 1994, and we are delighted to be re-publishing it in 2013 to a brand new audience of thriller fans.

In March 1959, after the failure of the revolt by the Tibetan people against their Chinese masters, the Dalai Lama escaped to India with the help of the CIA and British Intelligence sources. A remarkable affair indeed. But three years later the British masterminded an even more remarkable coup. It went something like this …

1

They were closer now, he could hear the savage barking of the dogs, the voices of his pursuers calling to each other, firing at random as he ran headlong through the trees. There was a chance, not much of a one, if he could reach the river and cross to the other side. Another country and home free. He slipped and fell, rolling over and over as the ground sloped. As he got to his feet there was an enormous clap of thunder, the skies opened and rain fell in a great curtain, blanketing everything. No scent for the dogs now and he started to run again, laughing wildly, aware of the sound of the river, very close now, knowing that he’d won again this damned game he’d been playing for so long. He burst out of the trees and found himself on a bluff, the river swollen and angry below him, mist shrouding the other side. It was at that moment that another volley of rifle shots rang out. A solid hammerlike blow on his left shoulder punched him forward over the edge of the bluff into the swirling waters. He seemed to go down for ever, then started to kick desperately, trying for the surface, a surface that wasn’t there. He was choking now, at the final end of things and still fighting and, suddenly, he broke through and took a great lungful of air.

Paul Chavasse came awake with a start. The room was in darkness. He was sprawled in one of the two great armchairs which stood on either side of the fireplace and the fire was low, the only light in the room on a dark November evening. The file from the Bureau which he’d been reading was on the floor at his feet. He must have dozed, and then the dream. Strange, he hadn’t had that one in years, but it was real enough and his hand instinctively touched his left shoulder where the old scar was still plain to see. A long time ago.

The clock on the mantelshelf chimed six times and he got to his feet and reached to turn on the lamp on the table beside him. He hesitated, remembering, and moved to the windows where the curtains were still open. He peered out into St Martin’s Square.

It was as quiet as usual, the gardens and trees in the centre touched by fog. There was a light on at the windows of the church opposite, the usual number of parked cars. Then there was a movement in the shadows by the garden railings opposite the house and the woman was there again. Old-fashioned trilby hat, what looked like a Burberry trenchcoat and a skirt beneath, reaching to the ankles. She stood there in the light of a lamp, looking across at the house, then slipped back into the shadows, an elusive figure.

Chavasse drew the curtains, switched on the other lights and picked up the phone. He called through to the basement flat where Earl Jackson, his official driver from the Ministry of Defence, lived with his wife, Lucy, who acted as cook and housekeeper.

Jackson’s voice had a hard cockney edge to it. ‘What can I do for you, Sir Paul?’

Chavasse winced. He still couldn’t get used to the title, which was hardly surprising for he had only been knighted by the Queen a week previously.

‘Listen, Earl, there’s a strange woman lurking around in the shadows opposite. Wears an old trilby hat, Burberry, skirt down to the ankles. Could be a bag lady, but it’s the third night running that I’ve seen her. Somehow I get a funny feeling.’

‘That’s why you’re still here,’ Jackson said. ‘I’ll check her out.’

‘Take it easy,’ Chavasse told him. ‘Send Lucy to the corner shop and she can have a look on the way. Less obvious.’

‘Leave it with me,’ Jackson said. ‘Are we going out?’

‘Well, I need to eat. Let’s make it the Garrick. I’ll be ready at seven.’

He shaved first, an old habit, showered afterwards then towelled himself vigorously. He paused to touch the scar of the bullet wound on the left shoulder, then ran his finger across a similar scar on his chest on the right side with the six-inch line below it where a very dangerous young woman had tried to gut him with a knife more years ago than he cared to remember.

He slipped the towel round his waist and combed his hair, white at the temples now but still dark, though not as dark as the eyes in a handsome, rather aristocratic face. The high cheek bones were a legacy of his Breton father, the slightly world-weary look of a man who had seen too much of the dark side of life.

‘Still, not bad for sixty-five, old stick,’ he said softly. ‘Only, what comes now? D-Day tomorrow!’

It was his private and not very funny joke, for the D stood for disposal and on the following day he was retiring from the Bureau, that most elusive of all sections of the British Secret Intelligence Service. Forty years, twenty as a field agent, another twenty as Chief after his old boss had died, not that it had turned out to be the usual kind of desk job, not with the Irish troubles.

So now it was all over, he told himself as he dressed quickly in soft white shirt and an easy-fitting suit by Armani in dark blue. No more passion, no more action by night, he thought as he knotted his tie. And no woman in his life to fall back on, although there had always been plenty available. The trouble was that the only one he had truly loved had died far too early and far too brutally. Even the revenge he had exacted had failed to take away the bitter taste. Yes, there had been women in his life, but never another he had wanted to marry.

He went into the drawing-room and picked up the phone. ‘I’m on my way, Earl.’

‘I’ll be ready, Sir Paul.’

Chavasse pulled on a navy blue raincoat, switched off the lights and went downstairs.

Earl Jackson was black, a fact which had given him no trouble at all with the more racist elements in the British Army, where he had served in both 1 Para and the SAS, mainly because he was six feet four in height and still a trim fifteen stone in spite of being forty-four years of age. He’d earned a Distinguished Conduct Medal in the Falklands and he and his wife, Lucy, had been with Chavasse for ten years now.

It had started to rain and when Chavasse opened the front door he found him waiting with a raised umbrella, very smart in grey uniform and peaked cap. As they went down the steps to the Jaguar, Chavasse glanced across at the garden. There was a slight movement in the shadows.

‘Still there?’

‘He certainly is,’ Jackson told him and opened the passenger door at the front, for Chavasse always sat next to him.

‘You mean it’s a man?’ Chavasse said as he got in.

Jackson shut the door, put the umbrella down, went round the car and slid behind the wheel. ‘But no ordinary man.’ He started the engine. ‘Lucy says he’s sort of Chinese.’

Jackson drove away and Chavasse said, ‘What does she mean by sort of?’

‘She says there’s something different about him. Not really like any Chinese she knows and quite different from those Thais and Koreans you see in their restaurants.’

Chavasse nodded. ‘And the skirt?’

‘She just got a glimpse while he was under the lamp. She said it seemed like some sort of robe and as far as she could make out in the bad light it was a kind of yellow colour.’

Chavasse frowned. ‘Curiouser and curiouser.’

‘You want me to do something about it, Sir Paul?’

‘Not for the moment,’ Chavasse told him, ‘and stop calling me Sir Paul. We’ve been together too long.’

‘I’ll do my best.’ Earl Jackson smiled. ‘But you’ll be wasting your time with Lucy. She just loves it.’ And he turned out on to the main road and picked up speed.

The porter at the Garrick, that most exclusive of London clubs, greeted him with a smile and took his coat.

‘Nice to see you, Sir Paul.’ He came out with the title as if he’d been doing it all his life.

Chavasse gave up and mounted the majestic staircase with its stunning collection of oil paintings and went into the bar. A couple of ageing gentlemen sat in the corner talking quietly, but otherwise the place was empty.

‘Good evening, Sir Paul,’ the barman said. There it was again. ‘Your usual?’

‘Why not?’

Chavasse went and sat in a corner, took out his old silver case and lit a cigarette while the barman brought a bottle of Bollinger RD champagne, opened it and poured. Chavasse tried it, nodded his satisfaction and the barman topped up the glass and retreated.

Chavasse toasted himself. ‘Well, here’s to you, old stick,’ he murmured. ‘But what comes next, that’s the thing?’

He emptied the glass rather quickly, refilled it and sat back. At that moment a young man entered, paused, glancing around, then approached him.

‘Sir Paul Chavasse? Terry Williams of the Prime Minister’s office.’

‘You must be new,’ Chavasse said. ‘I don’t think we’ve met.’

‘Very new, sir. We were trying to get hold of you and your housekeeper told us you would be here.’

‘Sounds urgent,’ Chavasse said.

‘The Prime Minister wanted a word, that’s the thing.’

Chavasse frowned. ‘Do you know what it’s about?’

‘I’m afraid not.’ Williams smiled cheerfully. ‘But I’m sure he’ll tell you himself. He’s on the way up.’

A moment later and John Major, the British Prime Minister, entered the bar.

His personal detective was behind him and waited by the entrance. The Prime Minister was in evening dress and smiled as he came forward and held out his hand.

‘Good to see you, Paul.’

Williams withdrew discreetly and Chavasse said, ‘Thank God you didn’t say Sir Paul. I’m damned if I can get used to it.’

John Major sat down. ‘You got used to being called the Chief for the past twenty years.’

‘Yes, well, that was carrying on a Bureau tradition set up by my predecessor,’ Chavasse told him. ‘Can I offer you a glass of champagne?’

‘No thanks. The reason for my rather glamorous appearance is that I’m on my way to a fund-raising affair at the Dorchester and they’ll try and thrust enough glasses of champagne on to me there.’

Chavasse raised his glass and toasted him. ‘Congratulations on your leadership victory, Prime Minister.’

‘Yes, I’m still here,’ Major said. ‘Both of us are.’

‘Not me,’ Chavasse reminded him. ‘Last day tomorrow.’

‘Yes, well, that’s what I wanted to speak to you about. How long have you been with the Bureau, Paul?’ He smiled. ‘Don’t answer, I’ve been through your record. Twenty years as a field agent, shot three times, knifed twice. You’ve had as many injuries as a National Hunt jockey.’

Chavasse smiled. ‘Just about.’

‘Then twenty as Chief and, thanks to the Irish situation, leading just as hazardous a life as when you were a field agent.’ The Prime Minister shook his head. ‘I don’t think we can let all that experience go.’

‘But my Knighthood,’ Chavasse said, ‘the ritual pat on the head on the way out. I must remind you, Prime Minister, that I’m sixty-five years of age.’

‘Nonsense,’ John Major told him. ‘Sixty-five going on fifty.’ He leaned forward. ‘All this trouble in what used to be Yugoslavia and Ireland is not proving as easy as we’d hoped.’ He shook his head. ‘No, Paul, we need you. I need you. Frankly, I haven’t even considered a successor.’

At that moment Williams came forward. ‘Sorry, Prime Minister, but I must remind you of the time.’

John Major nodded and stood. Chavasse did the same. ‘I don’t know what to say.’

‘Think about it and let me know.’ He shook Chavasse by the hand. ‘Must go. Let me hear from you.’ And he turned and walked out followed by his detective and Williams.

And think about it Chavasse did as he sat at the long table in the dining-room and had a cold lobster salad, washing it down with the rest of the champagne. It was crazy. All those years. A miracle that he’d survived, and just when he was out, they wanted him back in.

He had two cups of coffee then went downstairs, recovered his raincoat and went down the steps to the street. The Jaguar was parked nearby and Jackson was out in a second and had the door open.

‘Nice meal?’ he asked.

‘I can’t remember.’

Jackson got behind the wheel and started up. ‘You all right?’

Chavasse said, ‘What would you say if I told you the Prime Minister wants me to stay on?’

‘Good God!’ Jackson said and swerved slightly.

‘Exactly.’

‘Will you?’

‘I don’t know, Earl, I really don’t.’ And Chavasse lit a cigarette and leaned back.

As they reached the turning into St Martin’s Square Chavasse said, ‘Stop here. I’ll walk the rest of the way. Time I took a look for myself.’

‘You sure you’ll be all right?’ Jackson asked.

‘Of course. Give me the umbrella.’

Chavasse got out, put up the umbrella against the relentless rain and walked along the wet pavement until he came to the next turning which brought him into the square on the opposite side from his house. He paused. There was a touch of fog in the rain and he seemed to sense voices and laughter. He crossed to the entrance to the garden in the centre of the square.

The voices were clearer now, the laughter callous and brutal. He hurried forward and saw the mystery man clear in the light of a street lamp, being manhandled by three youths.

One of them wore a baseball cap and seemed to be the leader. He swatted the mystery man across the side of the head and the trilby hat went flying, revealing a shaven skull.

‘Christ, what have we got here?’ he demanded. ‘A bloody Chink. Hold him while I give him a slapping.’

Chavasse, seeing the man’s face clear in the light of the street lamp, knew what he was. Tibetan. The other two lads grabbed the man by the arms and the one in the baseball cap raised a fist.

Chavasse didn’t say a word, simply stamped hard against the back of the lad’s left knee, sending him sprawling. The youth lay there for a moment, glowering up.

‘Let’s call it a night,’ Chavasse said, putting down the umbrella.

The other two released the Tibetan and rushed in. Chavasse rammed the end of the umbrella hard into the groin of one and turned sideways, stamping on the kneecap of the second, sending him down with a cry of agony.

He heard a click behind and the Tibetan called, ‘Watch out!’

As Chavasse turned, the one in the baseball cap was on his feet, a switchblade in one hand, murder in his eyes. Earl Jackson seemed to materialize from the gloom like some dark shadow.

‘Can anyone join in?’ he enquired.

The youth turned and slashed at him.

Jackson caught the wrist with effortless ease, twisting hard, the youth dropping the knife and crying out in pain as something snapped.

Jackson picked up the knife, stepped on the blade and dropped it down the gutter drain. The other two were on their feet but in poor condition. Baseball cap was sobbing in pain.

‘Nigger bastard,’ he snarled.

‘That’s right, boy, and don’t you forget it. I’m your worst nightmare. Now go.’

They limped away together, disappearing into the night, and Chavasse said, ‘Good man, Earl. My thanks.’

‘Getting too old for this kind of game,’ Jackson said. ‘And so are you. Think about that.’

The Tibetan stood there holding his trilby, rain falling on the shaven head, the yellowing saffron robes beneath the raincoat indicating one thing only. That this was a Buddhist monk. He looked about thirty-five with a calm and placid face.

‘A violent world on occasion, Sir Paul.’

‘Well, you’re up to date at least,’ Chavasse told him. ‘Why have you been hanging around for the last three days?’

‘I wished to see you.’

‘Then why not knock on the door?’

‘I feared I might be turned away without the opportunity of seeing you. I am Tibetan.’

‘I can tell that.’

‘I know that I seem strange to many people. My appearance alarms some.’ He shrugged. ‘I thought it simpler to wait in the hope of seeing you in the street.’

‘Where you end up at the mercy of animals like those.’

The Tibetan shrugged. ‘They are young, they are foolish, they are not responsible. The fox kills the chicken. It is his nature. Should I then kill the fox?’

‘I sure as hell would if it was my chicken,’ Earl Jackson said.

‘But that would make me no follower of Lord Buddha.’ He turned, to Chavasse. ‘As you may see, I am a Buddhist monk. My name is Lama Moro. I am a monk in the Tibetan temple at Glen Aristoun in Scotland.’

‘Christ said that if a man slaps you across the cheek turn the other one, but he only told us to do it once,’ Chavasse said. Jackson laughed out loud. Chavasse carried on. ‘Have you eaten?’

‘A little rice this morning.’

Chavasse turned to Jackson. ‘Earl, take him to the kitchen. Let him discuss his diet with Lucy. Tell her to feed him. Then bring him up to me.’

‘You are a kind man, Sir Paul,’ Lama Moro said.

‘No, just a wet one,’ Chavasse told him. ‘So let’s get in out of the rain.’ And he led the way across the road.

* * *

It was an hour later when there was a knock at the drawing-room door and Lucy came in, the apple of Jackson’s eye, a face on her like some ancient Egyptian princess, her hair tied in a velvet bow, neat in a black dress and apron.

‘I’ve got him for you, Sir Paul. Lucky I had plenty of rice and vegetables in. He’s a nice man. I like him.’ She stood back and Moro entered in his saffron robes. ‘I’ve got his raincoat and hat in the cloakroom,’ she added and left.

Chavasse was sitting in one of the armchairs beside the fire, which burned brightly, a glass in his hand.

‘Come and sit down.’

‘You are too kind.’ Moro sat in the chair opposite.

‘I won’t offer you one of these.’ Chavasse raised the glass. ‘It’s Bushmills Irish whiskey, the oldest in the world some say and invented by monks.’

‘How enterprising.’

‘You’re a long way from home,’ Chavasse said.

‘Not really. I left Tibet with other refugees when I was fifteen years of age. That was in nineteen seventy-five.’

‘I see. And since then?’

‘Three years with the Dalai Lama in India then he arranged for me to go to Cambridge to your old college – Trinity. You were also at the Sorbonne. I too have studied there, but Harvard eluded me.’

‘You certainly know a great deal about me,’ Chavasse told him.

‘Oh, yes,’ Moro said calmly. ‘Your father was French.’

‘Breton,’ Chavasse said. ‘There is a difference.’

‘Of course. Your mother was English. You had a unique gift for languages which explains your studies at three of the world’s greatest universities. A Ph.D. at twenty-one, you returned to Cambridge to your own college, where they made you a Fellow at twenty-three. So there you were, at an exceptionally young age, set on an academic career at a great university.’

‘And then?’ Chavasse enquired.

‘You had a colleague at Trinity whose daughter was married to a Czech. When he died, she wanted to return to England with her children. The Communists refused to let her go and the British Foreign Office wouldn’t help.’ Moro shrugged. ‘You went in on your own initiative and got them out, sustaining a slight wound from a border guard’s rifle.’

‘Ah, the foolishness of youth,’ Chavasse said.

‘Safely back at Cambridge, you were visited by Sir Ian Moncrieff, known only as the Chief in Intelligence circles, the man who controlled the Bureau, the most secret of all British Intelligence units.’

‘Where in the hell did you get all this from?’ Chavasse demanded.

‘Sources of my own,’ Moro told him. ‘Twenty years in the field for the Bureau and twenty years as Chief after Moncrieff’s death. A remarkable record.’

‘The only thing remarkable about it is that I’m still here,’ Chavasse said. ‘Now who exactly are you?’

‘As I told you, I’m from the Tibetan temple at Glen Aristoun in Scotland.’

‘I’ve heard of it,’ Chavasse told him. ‘A Buddhist community.’

‘I live and work there. I am the librarian. I have been collating information on the escape of the Dalai Lama from Tibet in March 1959.’

A great light dawned. ‘Oh, I see now,’ Chavasse said. ‘You’ve found out that I was there. That I was one of those who got him out.’

‘Yes, I know all about that, Sir Paul, heard of those adventures from the Dalai Lama’s own lips. No, it is what comes after that interests me.’

‘And what would that be?’ Chavasse asked warily.

‘In nineteen sixty-two, exactly three years after you helped the Dalai Lama to escape, you returned to Tibet to the town of Changu to effect the escape of Dr Karl Hoffner who worked as a medical missionary in the area for years.’

‘Karl Hoffner?’ Chavasse said.

‘One of the greatest mathematicians of the century,’ Moro said. ‘As great as Einstein.’ He was almost impatient now. ‘Come, Sir Paul, I know from sound sources that you undertook the mission and yet there is no record of Hoffner other than his time in Tibet. Did he die there? What happened?’

‘Why do you wish to know?’

‘For the record. The history of my country’s troubled times under Chinese rule. Please, Sir Paul, is there any reason for secrecy after thirty-three years?’

‘No, I suppose not.’ Chavasse poured another whiskey. ‘All right. Strictly off the record, of course. Flight of fancy, when you put it on the page.’

‘I agree. You can trust me.’

Chavasse sipped a little Bushmills. ‘So, where to begin?’