Полная версия:

Icefalcon’s Quest

BARBARA HAMBLY

Icefalcon’s Quest

Copyright

Voyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © 1998 by Barbara Hambly

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006483038

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2014 ISBN: 9780007469208

Version: 2016-12-22

Dedication

For Neil Gaiman

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

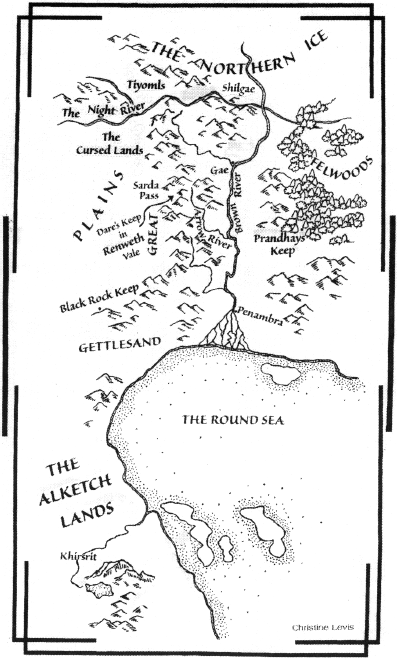

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Keep Reading

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Map

Chapter 1

Had the Icefalcon still been living among the Talking Stars People, the penalty for not recognizing the old man he encountered in the clearing by the four elm trees would have been the removal of his eyes, tongue, liver, heart, and brain, in that order. His head would have been cut off, and, the Talking Stars People being a thrifty folk, his hair taken for bowstrings, his skin for ritual leather, and his bones for tools and arrowheads. If it was a bad winter, they would have eaten his flesh, too, so it was just as well that his misdeed occurred in the middle of spring.

The Icefalcon considered all this logical and justified: the laws of his ancestors were not the reason that he no longer lived among the Talking Stars People.

All the horror that followed could have been avoided had he minded his own business, as was his wont. Sometimes he felt that he had spent entirely too much time living among civilized people.

It had been a bad year for bandits. The summer following the Summerless Year had seen more than the usual bloody strife in the rotting kingdoms that once made up the empire of the Alketch in the South, and bands of paid-off warriors, both black and white, drifted north to prey on the small communities along the Great Brown River. It was said they had penetrated far to the east, into the Felwoods, though few came so far north as the Vale of Renweth. Now it was spring again. When a woman’s screams and a man’s thin cries for help sliced the cold, sharp air of the Vale, the Icefalcon guessed immediately what was going on.

In the round clearing in the woods about three miles upslope from the Keep, he found pretty much what he expected to find. The scene was common in the river valleys these days: an old man lying with a great bleeding wound in his head by the remains of a small campfire, a donkey squealing and pulling its tether, and a burly, coal-black warrior of the Alketch in the process of dragging a buxom red-haired woman into the trees. In the filmy eggshell brightness of the spring afternoon the old man’s blood glared crimson, the warrior’s yellow coat in brilliant contrast to the emerald of the grass, the beryl of the close-crowding trees. The knife in the woman’s hand blinked like a mirror.

Seeing no point in making a target of himself by crossing the meadow openly, the Icefalcon ducked immediately back into the belt of hazel and chokecherry that ringed the clearing and kept to cover as he worked his way around. The woman was putting up a good fight. She was as tall as her attacker and of sturdy build, dressed as a man for travel in trousers and a padded wool jacket. Still, the man got the knife away from her, twisted her arm behind her, and seized her thick braids. The woman cried out in pain – she had not ceased to shriek throughout the encounter – and the Icefalcon simply stepped from behind an elm tree next to the struggling pair, flipped one of his several poignards into his hand, and slit the warrior’s throat.

The woman saw him a split second before he grabbed the man around the jaw to pull his head back for the kill. She screamed in what the Icefalcon considered unreasonable horror – what did she think he was going to do? – as the man’s blood soused over her breast and belly in a raw-smelling drench, and jumped away as her attacker collapsed between them. The Icefalcon had already turned, sword in hand, to scan the woods behind.

“Shut up,” he instructed. “I can’t hear anything.” A single bandit was even rarer than a single cockroach.

But there was no second attack. No sound in the woods, at least as far as he could tell over the woman’s hooting gasps.

He glanced back at her after the first quick check and pointed out, “Your companion is hurt.”

“Oh!” she cried. “Oh, Linok!” and rushed across the clearing to where the old man lay.

After looting the fallen body of weapons, the Icefalcon followed more slowly, listening, watching all around him, tallying sounds and half-guessed movements in the shadows of the trees. She’d made noise enough to have brought the armies clear from the Alketch, let alone from higher up the Vale.

He came up on her as she was dabbing clean the old man’s scalp. The cut looked ugly, blood smeared all over the round, brown, wrinkled face and matted dark in the salt-and-pepper hair. “Hethya?” moaned the old man, groping for her arm with a shaky hand.

“I’m here, Uncle. I’m all right.” Her jacket had been pulled nearly off her shoulders in the struggle, her tunic torn to the waist. She made nothing of her half-bared breasts, round and upstanding and white as suet puddings under the terra-cotta spill of her hair. The Icefalcon put her age at perhaps thirty, a few years older than himself. She had a red full mouth and the porcelain-fair skin of the Felwoods and an easterner’s way with vowels as well.

“We’re all right for now,” corrected the Icefalcon, still listening to the too silent woods. “Your visitor’s companions will be along at any time. How is it with you, old man? Can you back the donkey?”

“I – I believe so.” Old Linok had the well-bred speech of the capital at Gae, before the Dark Ones destroyed it along with most of the rest of the works of humankind. He sat up, clinging to his niece’s fleshy shoulder for support. “What happened? I don’t …”

“Your niece will explain on the way to the Keep.” Impossible that the bandit’s companions weren’t only minutes away – the Talking Stars People would have already left the old man behind. The Icefalcon had with some difficulty been taught to follow the dictates of civilized people about those too infirm to look out for themselves, but he still didn’t understand them. “Get him on the beast and don’t be a fool, woman,” he added, when she turned to gather up bedrolls and packs. “The bandits will have those one way or the other.”

“But we carried those clear from …”

“No, no, Hethya, the boy is right.” Linok struggled with maddening slowness to get himself upright. “There will be others. Of course there will be others.”

The Icefalcon already had the donkey over to them. He reminded himself that among civilized people it was not done to grab old men by the backs of their clothing and heave them onto pack-beasts like killed meat, no matter how much more efficient such a procedure might be for a speedy getaway. His sword was in his right hand, his attention returning again and again to the place in the trees where the birds were silent – somewhere between the big elm with the lightning scar and the three smaller elms close together.

“You’re from the fortress, aren’t you, young man?”

“Be silent, both of you.” He was too preoccupied with trying to track potential attackers by sound to inquire where else they thought he might have emerged from, if not the monstrous black block of the Keep, whose obsidian-smooth walls were visible from nearly any point in the lower part of the Vale.

They were there. He felt their presence as one sometimes felt the spirits of holy places, felt their eyes on the little party with all the training of his upbringing in the Real World, the empty lands beyond the mountains. He’d killed their companion and was in charge of two and perhaps three sets of weapons and a donkey, far rarer than gold in this devastated world. He and his companions were outnumbered …

So why didn’t they attack?

And why didn’t these two idiots he’d rescued shut up?

But they didn’t. And the bandits kept to the trees, invisible and unheard. As far as the Icefalcon could tell, they didn’t even follow them as they moved from clearing to clearing down the ice-fed stream, until they came to the open land that surrounded the Keep of Dare, the last refuge of humankind between the Great Brown River and the glacier-rimmed horns of the Snowy Mountains, somber towers blotting the western sky.

“You were fools not to come to the Keep when first you entered the valley.” The Icefalcon glanced back at them, man and woman, for the first time taking his eyes from the surrounding woods. “Where were you bound? You must have seen it.”

“Now listen here, boy-o,” began the woman Hethya, apparently indignant at being called a fool, though the Icefalcon would have been hard put to devise another term that covered the situation.

“No, niece, he’s right,” Linok sighed. “He’s right.” He straightened his bowed back – he was a little, round-faced, stooped man, with blunt-fingered hands clinging to the ass’ short-cropped mane – and looked back at the Icefalcon walking behind them, long, curved killing-sword still in hand.

“A White Raider, aren’t you, my boy? And clothed as one of the King’s Guard of Gae.”

Civilized people, the Icefalcon had discovered, loved to state the obvious. In the improbable event that a man of the Realm of Darwath – and they were a dark-haired people on the whole – had been flax-blond and grew his hair long enough to braid, it was still unlikely in the extreme that he’d have had dried hand bones plaited into the ends of it.

The bones were those of a man who had poisoned the Icefalcon, stolen his horse and the amulet that guarded him from the Dark Ones, and left him to die. The Icefalcon saw no reason for civilized people to be shocked about this, but mostly they were.

“Had you journeyed as far as we have, young man,” Linok went on, shaking a finger at him, “in such lands as the Felwoods have become in the seven years since the coming of the Dark, you’d beware of anyone and anything you don’t know, too. Cities that once were bywords of law and hospitality are nests now of ghouls and thieves …”

His gestures widened to dramatic sweeps, like an actor declaiming. The Icefalcon wondered if Linok sincerely believed that the Icefalcon had somehow missed these events or if he simply liked to hear himself talk, a failing common among civilized people who didn’t have to deal with the possibility of death by starvation or violence as the result of ill-timed sound.

“The very Keeps themselves are no longer safe. Prandhays Keep, once the stronghold of the landchief Degedna Marina, was breached and overtaken by outlaws who nearly killed us when we came there seeking shelter. There is no trust to be found anywhere in this sorry and desolated world.”

“Still,” said Hethya softly, “it is not so bad as it was.” Her voice altered, the broad dialect of the Felwoods lands transmuting into something else, her carriage changing, as if she grew taller where she walked at the donkey’s head. “Nathión Aysas intios tá, they used to say: The Darkness covered the very eyes of God.”

The Icefalcon tilted his head at the unfamiliar words, of no language that he knew or had ever heard. There was the echo of dark horror in the woman’s eyes, and her whole face, in its frame of cinnamon curls, grew subtly different.

“You mean in the days when the Dark Ones rose,” he said.

Her laugh was soft, bitter, and strange, out of place in the lush – featured face. “Yes,” she said. “I mean when the Dark Ones rose.”

Around them in the open meadow a half hundred or so sheep fled bleating, and the dozen cows raised their heads to regard them with the mild stupid curiosity of bovine kind: all the livestock left to a community of some five thousand souls. The pasturage had been shifted again, as the rubbery, alien growth called slunch spread into what had been the Keep’s cornfields, and only a few of the fields themselves remained. The ice storm that struck in the Summerless Year had accounted not only for most of the stock, but for all but a few of the fruit trees as well, freezing them to their hearts. Even the spells of the Keep’s mages had been unable to revive more than a handful. Raised by magic three and a half millennia ago, the black walls of the Keep itself stood isolated in the desolation.

Still, they stood, impervious to horror, night, and Fimbul winter in a world of glacier-crowned rock, and Hethya looked on them across the meadow with sadness and knowledge in her eyes.

“Not the rising of the Dark Ones that you remember, barbarian child,” she added softly. “Not their brief, final rising, when they wiped out the last of humankind before themselves passing on into another dimension of the cosmos.” Her hand shifted on the donkey’s bridle, and she seemed oblivious now to the dead bandit’s blood crusted on her clothing.

“I remember the days when the Dark Ones rose like a black miasma and did not depart. Not in a season, not in a year, not in a generation. I remember the days when humankind shrank to handfuls, not daring to leave the black walls of its Keeps for years at a time, fearing the night, fearing the day almost as much. When the world we knew was rent asunder and all the things that we cherished were swept away so that not even the words for them remained.

“I remember,” she said. “It was three and a half thousand years ago, but I remember what it was like, at the original rising of the Dark. I was there.”

“I don’t know how young I was,” said Hethya, sipping the tisane of hot barley that Gil-Shalos of the Guards brought her, “when she first started speaking to me in me mind.”

She drew up her legs under the borrowed skirts of homespun wool – worn and mended like everything in the Keep these days – and looked around her at the notables of the Keep assembled in the smallest of the royal council chambers.

“Six or seven, I think. I know I startled Mother – and horrified me aunties – by some of what I’d come out with, things no young girl ought to think or know.”

Her wry grin summoned back for a moment that red-haired child, with her pointed chin and wide-set cheekbones and innocent hazel eyes, in a house whose diamond-paned window casements would have been left open after dark to catch the evening breeze. In her smile the Icefalcon, seated with Gil-Shalos and a couple of other warriors near the door, could glimpse the reflection of parents and siblings who had mostly died uncomprehending, terrified, one night when the thin acid winds blew cold from the shadows and the shadows themselves flowed out to drown the light.

Minalde asked, “Does she have a name?” She leaned forward, dark braid swaying over the faded red wool of her state gown, twined with the pearls of the ancient Royal House.

Hethya’s tawny brows tugged together. “Oale Niu,” she said at length. “Though I don’t know whether this is her name or her title. She calls herself other things sometimes.”

The Icefalcon saw the glance that passed around the room, the murmur of wonderment and question like wind rustling the aspens by the orchards. Even the Keep Lords, the few members of the ancient Gae nobility who’d managed to make it to the Keep with food stores and servants and miniature armies of retainers and guards, were impressed, and they tended not to be moved by anything that didn’t directly impinge on their real or imagined privileges. Lord Ankres muttered something to Lord Sketh, who nodded, blue eyes bulging. Three of the Keep’s four mages – Rudy, Wend, and Ilae – leaned forward on their bench of smooth-whittled pine poles, draped in mammoth and bison-hides. Wise Ones, the Icefalcon’s people would have called them, they had summoned spots of glowing witchlight to augment the flickering amber of the small, round hearth, but the blue-white light burned low, giving the big double cell the intimacy of a private chamber.

“Oale Niu,” Minalde repeated softly, tasting the shape of that name with a kind of wonder. The Lady of the Keep and widow of Eldor, the last High King of the Realm of Darwath, had changed a great deal from the shy seventeen-year-old the Icefalcon had rescued from the Dark Ones seven years ago. Thin-boned and delicately beautiful, with lupine-blue eyes that had seen too much: a pawn who had worked her heartbreaking way across the chessboard to become not a queen, but a king.

“And you remember to her?” asked Altir Endorion, Lord of the Keep of Dare.

He had his mother Minalde’s eyes, large and blue as the hearts of the deepest-hued morning glories, and her coal-black hair. Of his father, he had the memories of the House of Dare, memories of the line that stretched unbroken back to the original Time of the Dark; memories uncertain, patchy, in no particular order, memories of other people’s mothers, other people’s griefs. Some members of his house had been spared these memories, the Icefalcon had been told. Others had had them only in flashes, or sometimes in the form of hurtful, restless dreams. Minalde had them, too, inherited from the House of Bes, a collateral of Dare’s line. Sometimes Tir’s eyes were three thousand years old and more.

He’d be eight in high summer and looked it now, small face filled with wonder as he gazed up at this newcomer from another world.

Hethya smiled looking down at him, and her expression softened. “I don’t remember to her, me little lord,” she said. “I – I am her, in a way of speaking. Sometimes. She’s like in a room in me head” – she tapped her temple – “and sometimes she only sits in that room talking to me, and sometimes she comes out, and … and then I have to sit in that room, and listen to the things she says, and watch the things she does with me hands, and me feet, and me body.”

Her brow creased again, and some remembered pain hardened a corner of her mouth. She looked aside from Tir’s too innocent eyes.

After a moment she went on, “Sometimes she’ll tell me things, or show me things, things about the Times Before. It’s hard to explain the way of it, between her and me.”

“Rudy?” Minalde looked across to the young mage who was her lover, seated at a discreet distance with his two colleagues in wizardry out of respect for the sensibilities – religious or political – of the Keep Lords and the Bishop Maia. “Have you ever heard of such a thing?”

Rudy Solis shook his head. He, too, had changed, the Icefalcon thought, over the past seven years. Like Gil-Shalos he was an outlander, son of an alien world. When they had arrived in the train of Ingold the Wizard on the morning following the final destruction of Gae, the Icefalcon had guessed immediately that Gil-Shalos, who now sat beside him in the loose black clothing of the Guards, would survive. He had seen the warrior in her eyes.

Rudy he had not been so sure of. Even after the young man had found in himself the powers of the Wise Ones – powers that evidently did not exist or were not accessible to humans in his own world – the Icefalcon would not have bet the runt of a pot dog’s litter on Rudy’s survival. He might do so today, he thought, but not much more. For all that Rudy had been through, under Ingold’s tutelage and on his own, like many civilized people he lacked the cutting blade of hardness in his soul.

“I’ve never heard of anything of the kind,” he said. “Neither has Ingold, as far as I know. At least he’s never mentioned it to me.” He shook his long dark hair from his eyes, an unprepossessing figure in his laborer’s clothes and his vest of brightly painted bison-hide. “When we’re done here, I’ll contact him and ask.”

“It is a most inopportune moment,” put in the elderly Lord Ankres dryly, “for Lord Ingold to have absented himself from the Keep.”

Gil-Shalos stiffened at this slight to the mage who was her lover, her life, and the father of her young son, but as a member of the Guards it was not her place to speak out of turn to one of the Keep Lords. Rudy answered, however.

“When you come to think of it, my Lord, there never is an opportune moment for Ingold to go scavenging. I mean, hell, nothing ever happens in the winter because the bandits and the White Raiders are as locked down by the weather as we are, but then Ingold can’t get out, either. The only times he can get to the ruins of the cities is in summer. Are you saying you’d rather he didn’t find stuff like sulfur and vitriol to kill the slunch in the fields? Or books?”

“He could leave the books for another time,” responded the stout Lord Sketh. “There are things we need more.”

“Like a new brain for you, meathead?” muttered Gil under her breath.

“Be that as it may,” Minalde intervened, with her usual artlessly exact timing, “the fact is that Lord Ingold is at Gae just now and can be contacted easily by any of the mages here. Wend? Ilae? Have either of you heard tell of such a thing, that one of the wizards of the Times Before should possess the mind and soul of someone in our times?”

Both the dark-eyed little ex-priest and the slim young woman shook their heads. Their ignorance was scarcely a surprise, as neither had received formal training in wizardry. The Dark Ones had been hideously efficient in wiping out the schools in the City of Wizards and everyone else with obvious ability in the art.

“Well, I’ve never heard of such, either,” said Hethya. “And believe me, your Ladyship, I’ve looked.”

“It is a rare – a very rare – phenomenon.” Uncle Linok spoke for the first time, from the corner by the hearth. He adjusted the shawls and blankets wrapped about him, wool and fur and the combed and spun underwool of the mammoth, yak, rhinoceros, and uintatheria that the Keep’s hunters trapped and speared in the winter when the great lumbering animals migrated from the North.