Полная версия:

Who Owns England?

That figure has recently been convincingly challenged by two statisticians, John Beckett and Michael Turner. They examined land sales data from the time and found that ‘much less than 25 per cent of England changed hands in the four highlighted years 1918–1921’. Instead, they concluded, it was actually more like 6.5 per cent, and that excitable estate agents at the Gazette had massively overstated the case.

Moreover, all sides agree that the highest echelons of the aristocracy were able to cling on to their landed estates with much greater success than the lesser gentry. As Thompson quietly admits in the final pages of his book, ‘The landed aristocracy has survived with far fewer casualties … Among the great ducal seats, for example … Badminton, Woburn, Chatsworth, Euston Hall, Blenheim Palace, Arundel Castle, Alnwick Castle, Albury and Syon House, Goodwood, Belvoir Castle, Berry Pomeroy, and Strathfield Saye are all lived in by the descendants of their nineteenth-century owners.’ That Thompson could say this half a century after his supposed ‘revolution in landownership’ is startling enough. It’s even more startling, then, that today, another half-century on, every single one of those ducal family seats still remains in the hands of the same aristocratic families.

What may have felt seismic at the time looks a good deal less drastic in retrospect. ‘When Thompson wrote in 1963, the great estate seemed to be in terminal decline,’ argue Beckett and Turner, ‘but the subsequent revival of the fortunes of landed society [have] brought seriously into question the whole business of just how bad things really were.’

At the same time as Thompson was performing the last rites on the aristocracy, another author found them to be in rude health, albeit rather leaner. The journalist Roy Perrott’s 1967 survey, The Aristocrats, surveyed the acreage held by seventy-six titled landowners. Though most of the estates had significantly diminished in size since 1873, together these individuals still owned a combined 2.5 million acres across the UK. Perrott estimated that this sample represented ‘about one-seventh of those owned by the titled nobility’, and his definition of that elite totalled around 3,000 people. So, in the era of the Space Race, 0.005 per cent of the UK population still owned 17.9 million acres of the country, or 30 per cent of the total land area.

Drawing on Perrott’s work, the geographer Doreen Massey arrived at a similar extrapolation a decade later, concluding that ‘in spite of the decline which they have undergone this century, the holdings of the landed aristocracy have by no means been reduced to insignificance’. Stephen Glover’s 1977 survey of thirty-three large landowners found that they owned 667,410 acres, a drop of almost two-thirds from the 1,869,573 acres those same estates had owned in 1873. Even taking into account the reduced acreages, Glover concluded, these people ‘remain – on paper at least – very rich men’, all the wealthier thanks to the rapid rise in land prices that occurred in the 1970s.

More recent estimates, too, strongly suggest that the aristocracy have held their own against the tide of history. Kevin Cahill’s Who Owns Britain, which draws upon multiple newspaper reports, obituaries and rich lists, presents figures for the 100 largest landowners in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Altogether, Cahill reckons these select few own some 4.8 million acres. Still, this is only about 6 per cent of the land area of the two countries, and without figures for the rest of the aristocracy, it’s hard to conclude from Cahill’s research who actually owns the majority of Britain. Nevertheless, his figure for the land owned by the UK’s twenty-four non-royal dukes is startling. With a total of over 1 million acres between them, these remain men of very broad acres. Moreover, as we’ll see, the places they own have increased enormously in value, leaving many of the peerage extremely wealthy.

Or take the figures stated by the Country Land and Business Association (CLA), who represent the landowning lobby in England and Wales; many aristocrats are known to be members. In a 2009 document, the CLA state that ‘Our 36,000 members own and manage over 50% of all of the rural land in England and Wales.’ A second CLA document from the same year clarifies that the rural land in their members’ possession totals five million hectares. So the 36,000 members of the CLA own 12.35 million acres, a third of England and Wales. Dan and Peter Snow, in their 2006 BBC documentary Whose Britain Is It Anyway?, came to the similar conclusion that the aristocracy and old landed families still own nearly a third of the UK overall.

Further confirmation that land remains in the hands of the few comes from agricultural statistics collected by the Department for the Environment, Farming and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) on the number and size of farms. Counting the number of farm holdings isn’t quite the same as tallying up landowners: many farms are tenanted, and lots will be ultimately owned by companies and councils rather than the aristocracy. But these are still useful proxy figures. DEFRA’s 2017 data shows there are 218,000 farm holdings in the UK, covering 43 million acres – 72 per cent of the land area. Even this figure suggests that a tiny fraction of the overall population own the bulk of the land, and given that this includes tenanted farms, it’s likely a big overestimate. But the department also publishes statistics for England alone which give a more interesting breakdown of the total acreages owned by farms of different sizes. This allows us to see that the majority of English soil is farmed by a much smaller set of large farms: 25,638 farm holdings cover 16.5 million acres, or 52 per cent of England’s land area.

What’s more, comparing these with official statistics from 1960, now buried in the National Archives, shows that there are a lot fewer but bigger farms today than sixty years ago. When Thompson wrote about the decline of the aristocracy in the first half of the twentieth century, he described how smaller farmers had started buying up the land sold off by big estates. But since Thompson penned his book, the concentration of land ownership has, if anything, been increasing again.

Pinning down precisely what the aristocracy still own, and what’s now owned by the newly wealthy or by smaller-scale farmers, remains difficult. A definitive answer will remain elusive until the Land Registry is fully opened up. From the figures and estimates reviewed here, though, it seems a safe bet to say that around a third of England and Wales remains in the hands of the aristocracy and landed gentry – and that half of England is owned by less than 1 per cent of the population.

The aristocracy, in other words, have adapted, trimmed their sails – and survived. Their tenacity recalls Tennyson’s ‘Ulysses’:

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are …

As the MP Chris Bryant puts it in his critical history of the aristocracy: ‘Far from dying away, they remain very much alive.’

That begs two further questions. What’s been the impact of so much land remaining in the hands of so few? And how have the aristocracy pulled off such a stunning feat of survival?

The image that most aristocratic estates present to the world is that of the grand country house, surrounded by beautiful parkland. From the yellow towers of the Duke of Rutland’s Belvoir Castle – used as a substitute for Windsor in Netflix series The Crown – to the golden limestone frontage of Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, stately homes are the acceptable face of feudalism. Today, a ‘cult of the country house’ has grown up in England that rightly venerates their sumptuous architecture and historic art collections – though often omitting mention of how such wealth came to be amassed.

We now flock in our thousands to visit these mansions, stroll in their formal parterre gardens, and walk our dogs in their acres of parkland. Less than a century ago, of course, such public access would have been unthinkable. Aristocratic parks were created precisely to keep the masses out, and provide solace for their masters when they returned from the business of court or the hustle and bustle of the city. Many were created by the process of forcible enclosure, during which whole villages were evicted to make way for deer and specimen trees. Now that large swathes of parkland are open to the public for walking and cycling, that violent history has faded.

Aristocratic parkland has also changed our very concept of the English countryside. Much of that is thanks to one man, the individual who has perhaps had the single greatest impact on the English landscape: Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. During the eighteenth century, Brown was the landscape gardener du jour; he worked on some 250 sites during his lifetime and his client list included the majority of the House of Lords. Brown literally moved mountains and diverted rivers to create the naturalistic vistas that he and his patrons desired. Graceful curving hillsides were moulded and stands of trees carefully pruned to lead the eye through the parkland towards a distant folly or the setting sun. John Phibbs, Brown’s biographer, estimates that he had a direct influence on half a million acres of England and Wales. ‘The astonishing scale of his work means that he did not just transform the English countryside,’ Phibbs writes, ‘but also our idea of what it is to be English and what England is.’ None of this, of course, would have happened without aristocratic cash.

Partly because of the scale of their influence, there is also a lingering sense nowadays that the aristocracy are the rightful guardians of our countryside. Many noble families profess their concerns about the environment on their estate websites, and act on them in their management plans. The motto of the Hussey family, inscribed on a crest above the front door of Scotney Castle in Kent, is Vix ea nostra voco – Latin for ‘I scarcely call these things our own’.fn2

This notion of the aristocracy as stewards of the landscape is deeply rooted. There seems little doubt that the aristocratic preoccupation with lineage and inheritance gives them a long-term perspective when it comes to managing land. After all, it’s in the interests of a lord to look after his estate, because he knows his descendants will inherit it. But asserting you’re merely a steward of the land – ‘scarcely calling it your own’, when your family has in fact had outright possession of it for hundreds of years – can be a convenient excuse for owning so much. ‘It doesn’t feel to me as if I’m sitting here and owning vast tracts of land, because I obviously share it with hundreds of thousands of people,’ the Duke of Northumberland claimed in the 2006 BBC documentary Whose Britain Is It Anyway? ‘Yes, but – you’re the owner,’ pointed out an incredulous Peter Snow. ‘I am the ultimate owner, I suppose,’ the duke reluctantly admitted. There’s also a risk that the manicured parks and exquisite gardens of the aristocracy blind us to their wider environmental impact. As George Monbiot has argued, ‘they tend to be 500 acres of pleasant greenery amidst 10,000 laid waste by the same owner’s plough’. And that’s not the worst of it.

It was 5 a.m. on a freezing October morning, and I was locked onto a 500-tonne digger in an aristocrat’s opencast coal mine.

The coal mine in question had been dug on land belonging to Viscount Matt Ridley, a prominent climate change sceptic, Times columnist and member of the House of Lords. I was part of a group that had trespassed on his land in order to shut down the mine for the day, in protest at its contribution to global warming. But our direct action wasn’t just intended to highlight the millions of tonnes of coal that had so far been extracted from this gigantic pit. It was also to point out how Viscount Ridley had used his platform in Parliament and the press to cast doubt on climate science, while continuing to draw significant income from a coal mine on his land.

We had entered the vast opencast mine on Ridley’s 15,000-acre Blagdon Estate in Northumberland under cover of darkness, making sure we arrived before work started. After climbing up onto the gantry of one of the giant coal excavators, we’d locked ourselves to it with bike locks around our necks. The vast walls of the mine with their exposed seams of anthracite lowered over us. We felt like the hobbits in Mordor. It was around an hour later when we were discovered by security, who initially joked that they thought we were Sunderland supporters coming to rub it in after Newcastle’s recent defeat.

The police inspector who arrived later wasn’t so amused, particularly after we refused to unlock. We’d come to prevent coal being dug up, and we weren’t going to leave quietly. This mine, after all, was on land belonging to an aristocrat who’d stated that ‘fossil fuels are not finished, not obsolete, not a bad thing’, declared that ‘climate change is good for the world’, and who was still downplaying its importance just weeks before the opening of the Paris climate talks. Though Ridley admitted his financial interest in the coal mines on his estate, he had never disclosed the size of the ‘wayleave’, or rental income, that he received from leasing it to a mining company. Investigative journalist Brendan Montague has estimated it to be worth millions of pounds annually.

The arrangement illustrates two things about the aristocracy: their capacity to lobby politically for policies that align with their landed interests; and the way they use their monopoly over large tracts of land to extract rents. Indeed, many members of the peerage own extensive mineral rights across England, in addition to the land itself. The Duke of Bedford, for example, grew rich off the huge copper and arsenic mines that operated on his land at the Devon Great Consols during the Victorian period. The Duke of Devonshire is the only person in the UK to own the rights to any oil beneath his land, because he sank the first oil well on his estate at Hardstoft in Derbyshire before the 1934 Petroleum Act vested such rights in the Crown. He also has other mineral rights stretching far further afield: residents of Carlisle were surprised to receive letters in the post in 2013 notifying them that the Duke was staking his claim to metals and ores beneath their homes.

In fairness to them, many aristocrats nowadays are suspicious of letting extractive industries run riot on their estates. Plenty of large landowners have voiced their opposition to the fracking industry – such as Viscount Cowdray, who’s resisted efforts to explore for shale gas in the South Downs, and an alliance of baronets and earls who have refused fracking firm INEOS access to their lands in North Yorkshire.

But the prospect of a fresh source of rental income can be enticing to large estates. Renting out land, after all, requires little effort on the part of the landowner. As historian M.L. Bush argues, throughout its history the English aristocracy has remained ‘rigidly divorced … from direct production’ and ‘preferred the rentier role’ as a means of getting filthy rich without getting their hands dirty.

It’s this combination of inherited wealth and rent-seeking indigence that has drawn down much scorn upon the aristocracy in previous eras. ‘The rent of land is naturally a monopoly price,’ pointed out the classical free-market economist Adam Smith. ‘It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land … but to what the [tenant] can afford to give.’

John Maynard Keynes longed for ‘the euthanasia of the rentier’, noting that landlords need not work to obtain their income: ‘the owner of land can obtain rent because land is scarce’. It’s no coincidence that vampires were portrayed in Victorian gothic horror novels as being bloodsucking aristocrats, preying parasitically upon the lower classes. Indeed, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is not merely a count but a property magnate, buying up a string of big houses in London as places to leave his earth-filled coffins.

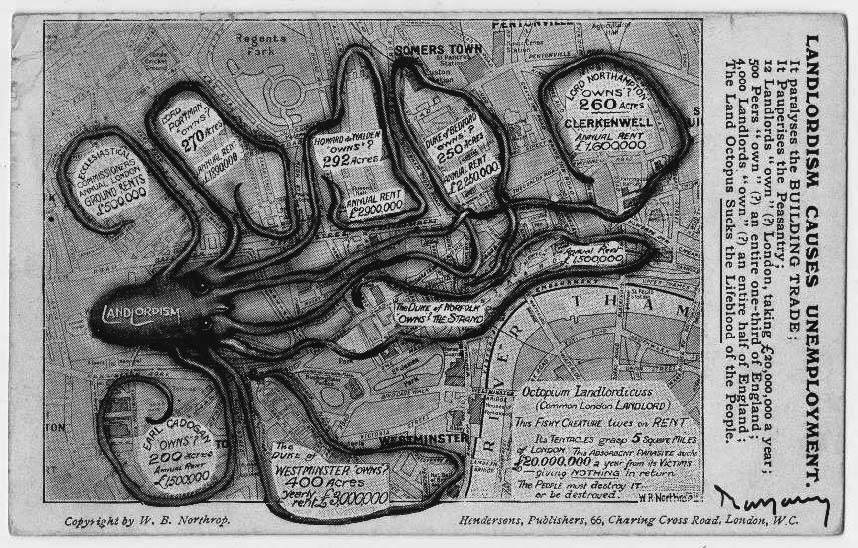

The most lucrative rental income, of course, went to aristocrats who owned land in central London. A 1925 campaigning postcard by radical journalist W.B. Northrop (see opposite) depicts a giant octopus labelled ‘landlordism’, its tentacles spreading through the streets of the capital. Each tendril curls around the boundaries of one of the ‘Great Estates’ that own London, listing their acreages and annual rents. ‘The Land Octopus Sucks the Lifeblood of the People,’ Northrop declared. Tellingly, nearly all of the aristocratic estates shown on the postcard still possess large swathes of the city today. Where they have lost land, they have more than made up for it in soaring property prices on their remaining acres.

You can walk from Sloane Square to Regent’s Park without leaving land owned by the aristocracy and the Crown. One hundred acres of Mayfair and 200 acres of Belgravia are owned by the Duke of Westminster’s Grosvenor Estate. The Duke’s property empire includes the most expensive street in the country, Grosvenor Crescent – average house price: £16.9 million – and Grosvenor Square, famous as the scene of the 1968 Vietnam War protests and, until recently, the base for the US embassy. The family inherited the land when it was merely swampy fields in the seventeenth century, as the wedding dowry of a marriage between the Grosvenors and infant heiress Mary Davies.

The octopus of ‘Landlordism’.

To the north of Oxford Street is the Portman Estate. Comprising 110 acres of properties in Marylebone, the estate was first acquired in 1532 by Sir William Portman, lord chief justice to Henry VIII, who bought it to graze goats. Like the other great estates, the bequest began as farmland and ended up as prime real estate, following a building boom in the Georgian period. Today, the 10th Viscount Portman is the inheritor of a £2 billion fortune, according to the Sunday Times Rich List. Next door is the Howard de Walden Estate, consisting of 92 acres of Marylebone and taking in famously fashionable Harley Street. It’s been owned by the de Walden family since 1710; the current head of the clan, Mary Hazel Caridwen Czernin, 10th Baroness Howard de Walden, is worth an estimated £3.73 billion.

To the south of Hyde Park is the Cadogan Estate, a 93-acre stretch of Kensington and Chelsea, inheritance of Earl Cadogan. This is the borough of the Grenfell Tower disaster, which left seventy-one dead and hundreds more homeless for months. It’s also a borough which, in 2017, had over 1,500 empty homes, many of which are rumoured to be within the Cadogan Estate, dubbed by journalists ‘the ghost town of the super-rich’. With an estimated wealth of £6.5 billion, Lord Cadogan’s family has a knowing motto: ‘He who envies is the lesser man’. Still, that fortune has been subsidised by the taxpayer and built off the back of ‘lesser men’: the GMB union calculated that in 2014 the Cadogan Estate had received £116,000 in housing benefit from less-well-off tenants.

These four aristocratic estates have a combined wealth of over £20 billion. Almost a thousand acres of central London remains in the hands of the aristocracy, Church Commissioners and Crown Estate. They own most of what is worth owning in central London. The character of the West End, argues the historian Peter Thorold, has been largely determined by the fact that ‘a small number of rich families held fast to their land over a long period of time.’ This level of aristocratic control has undoubtedly led to some well-planned squares and beautiful architecture. But even Simon Jenkins, the veteran defender of London’s historic buildings, admits this has come with its downsides. The Great Estates grew so powerful, Jenkins recounts, that they ‘managed for half a century to delay the introduction of a system of local government which might have mitigated the hardship it brought in its train’.

Crucial to the wealth of London’s aristocratic estates has been their ability to retain the freehold ownership of their land and properties. For most of their history, this was never in question. Each estate has hundreds of tenants, but they are sold their properties on long leases, so that the landlord retains ultimate control. In more recent decades, however, successive governments have sought to enact leaseholder reform, to allow long-term tenants to extend their leases and eventually buy from their landlords the properties they have lived in for decades. When John Major announced reforms to this effect in 1993, the Duke of Westminster resigned from the Conservative Party in disgust. But the Great Estates are very far from beaten. In a recent landmark court case, attempts to reduce the costs for leaseholders of buying out the properties they rent were quashed, in a victory for London’s aristocratic landlords.

While the aristocracy tend to make most of their money from their urban estates, where they spend it has an even bigger impact on the land. It’s in the English uplands where the influence of the landed gentry is most marked, and at its most malign: the vast acreages of our countryside given over to grouse moors.

The aristocracy have always engaged in bloodsports: from accompanying Norman kings to hunt deer and wild boar, to rearing pheasants for woodland shooting parties of the sort satirised in Roald Dahl’s Danny the Champion of the World. Who gets to catch and eat the creatures of the forest has long been a bone of contention between the landed and the landless; for centuries, poaching by hungry commoners was viciously policed. The mantrap in which Danny’s father gets snared when out poaching pheasants one night was once commonplace. New Labour’s ban on fox hunting was widely seen as retaliation for Thatcher crushing the miners’ strike: you routed the working class, so we’re bashing the toffs. But though foxhunts and pheasant shoots raise questions about class warfare and animal welfare, neither has anything like the impact on the landscape itself of shooting grouse.

A staggering 550,000 acres of England is given over to grouse moors – an area of land the size of Greater London. But despite the enormous scale of the grouse industry, few are aware of it: until recently there were no public maps showing its extent, and most of the research into grouse is carried out by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust and the Moorland Association, both funded by the owners of grouse moors. A few years ago, the Moorland Association quietly published a map on their website showing the approximate outline of grouse moors in England. After they refused to share the underlying data with me, I was able to extract it from their map with the help of a data analyst, sense-check it against aerial photographs, and publish the results on whoownsengland.org.

The management of driven grouse moors has had a profound and very visible impact on landscapes. Take a look on Google Earth at any of the upland areas of northern England, and you’ll soon spot the tell-tale patterns where the moorland heather has been slashed and burned to encourage the growth of fresh shoots favoured by young grouse. But to really appreciate the bleak devastation of a grouse moor, you need to visit one. An estate I walked across in the Peak District looked like a war zone: charred vegetation, scorched earth, deep gullies in the peat worn by rainwater flashing off the denuded soils. Studies by Leeds University have shown that the intensive management of grouse moors through heather burning can dry out the underlying peat, lead to soil carbon loss, and worsen flooding downstream. Residents of Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire live in the shadow of the huge Walshaw Moor Estate, a grouse shoot so intensively managed that the RSPB lodged a complaint against it with the European Court of Justice. For years, the local residents had warned about the potential ill-effects of having such a degraded ecosystem upstream from them. In winter 2015, disaster struck, with intense rainfall pouring off the hills and inundating many homes, not just in Hebden but downstream as far as Leeds. Grouse moors may seem remote from the lives of most people, but they can still have an impact on those living far from them.