Полная версия:

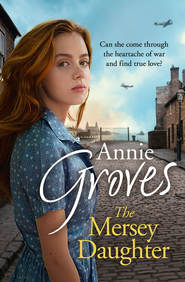

The Mersey Daughter: A heartwarming Saga full of tears and triumph

‘Can’t you go and see them?’ Violet wanted to know. ‘You can’t be at that hospital every day, week in, week out.’

Rita bit her lip. ‘It’s just that bit too far to do on my own. You can’t rely on trains or buses and they’re rather out in the sticks. Also, I get called in for extra shifts all the time – you know what it’s like. Every time there’s a direct hit on the docks or anywhere around here I could be needed and I hate to say no.’

‘Of course,’ Violet nodded. But she could sense her friend wanted to say more.

Rita glanced behind her, as if to check the inner door was firmly closed. ‘Besides, I’m needed here,’ she said quietly. ‘Winnie’s not been herself ever since I got the children back. She used to run this place like clockwork, but now she doesn’t seem to bother about anything – not the orders, or the cashing up, or filling the shelves. I have to try to keep on top of that as well as everything else.’ Her expression gave away just how tiring she was finding it.

‘Oh, I’m sorry to hear that, I hadn’t quite realised,’ Violet said. ‘You can’t do everything, you know. Maybe I could help? I’m not very organised but I can talk to the customers all right.’

Rita smiled in gratitude. ‘I know you could; you’d charm them and they’d love it. But you’re so busy already, what with helping with little George and the WVS, and aren’t you helping Mam with the new victory garden too? You’ve got your hands full.’

Violet shrugged. ‘That’s as may be, but you think about it. If I can be of any use I will – as long as you don’t expect me to do any sums. I never was any good at maths, just you ask my Eddy.’

‘Oh, I will, next time we see him.’ Rita cheered up at the mention of her brother, who everyone thought of as the quiet one in the family, but who had a wicked sense of humour. ‘Don’t let me keep you. Did you want anything?’

‘Some strong string,’ said Violet, reaching for her purse. ‘I’m going to mark out seed drills in the new plot. One of the old fellows from the Home Guard showed me how. We’ll all have fresh carrots and be able to see in the dark.’ She waved brightly and was on her way.

Rita grew solemn again as soon as she’d gone. Violet was a breath of fresh air, all right, but she’d feel bad asking her to help out any more than she already did. Besides, it was the sums that most needed attention. Rita had only just realised that the shop wasn’t making anything like the income it had before Christmas, and she had no idea what to do about it. They needed the money – now Charlie had given up any pretence of providing for them. But there was no time to think about it now. She checked her watch, knowing that she’d have to set off for the hospital any minute.

‘Winnie!’ she called through the inner door. ‘Are you ready to take over? I’ve got to get going.’

There was a shuffling and then Winnie slumped reluctantly along the corridor. ‘When are you going to give up that ridiculous nursing job?’ she demanded. ‘Your place is here, looking after the shop and me. Now you’ve driven Charles away, it’s the least you can do.’

Rita closed her eyes for a moment and prayed for strength. She would not rise to the vicious old woman’s bait. ‘I’ll see you later,’ she said instead, picking up her bag and jacket and making her way through the meagre stock to the outside door. She wrinkled her nose. It was still morning – but was that sherry she’d smelt on her mother-in-law’s breath?

CHAPTER SIX

‘Blast!’ Laura sat back on her heels and groaned. ‘You must think I’m a waste of space, Kitty, but this is much harder work than I’d ever have imagined.’ She wrung the grey water out from her damp cloth over the galvanised bucket. The sleeves of her overall were dripping from where they’d come unrolled.

It seemed that all they’d done since arriving was to clean the building, scrubbing and polishing, even though it had evidently been scrubbed and polished to within an inch of its life already by the previous band of new recruits, and alternating this with gruelling rounds of PT. The girls had also been sent on errands around London, taking urgent papers between offices, dishing out tea at important meetings and generally making themselves useful. Kitty had found it a shock to the system. She’d been accustomed to lifting enormous heavy pans of stew around the NAAFI canteen, but running around on her feet all day, minding her p’s and q’s whilst learning the ropes had been exhausting, and it had been almost impossible to take it all in. To begin with it had been hard to adjust to sleeping in their dormitory – which they were told to call a cabin. Soon they would also embark on a series of classroom lectures to learn the rules and regulations of the service, along with the endless jargon everyone used.

Kitty couldn’t help laughing at her friend. ‘It’s easier once you’re used to it,’ she said warmly. ‘Believe me, I know. I’ve been scrubbing floors since I was eleven – that’s when Mam died and I had to take over. Or even before that, as she couldn’t bend down when she was expecting our Tommy.’ A cloud passed across her face at the memory. ‘Anyway, they won’t have us doing this for long. It’s just to make good use of our time until we’re allocated our new positions.’

‘I hope you’re right,’ said the young woman who’d been assigned to clean the corridor with them. ‘This stuff is making my hands red raw. I wasn’t sure what to expect in our first week but it wasn’t this.’

Kitty regarded their new colleague with interest. She was slight, and had very pale skin and a smattering of freckles across her small upturned nose. While she was not conventionally pretty, she had striking looks and an air of determination and energy about her that somehow reminded Kitty of her old friend Rita back in Empire Street. ‘I bet they think that as long as they have a group of women together they might as well set us to clean up the place,’ she said, shaking the bristles of her scrubbing brush with vigour. ‘But I’m sure they’ll start training us to do something else once we’re all here and the place is shipshape. What did you do before?’

The girl raised an eyebrow. ‘I was a teacher.’

‘A teacher!’ Kitty gasped. ‘You don’t look old enough … sorry, I don’t mean to be rude, but …’

‘I’m older than I look,’ said the girl. ‘Don’t worry, everyone says the same to me. I’m twenty-three. I trained for two years, and then all the kids got evacuated, and I thought, “Marjorie, my girl, you’d better find something else to do with yourself and do it sharpish.” So here I am.’ She shrugged.

Kitty couldn’t help staring. Nobody from Empire Street had ever been a teacher, much less any of the women. Hardly anyone stayed at school longer than they had to; they were all needed to go out and work, or help raise the families, or both. It was all she could do to stop her mouth gaping open. ‘Well, at least you’ll be all right with these lectures we’re going to have to go to. I can hardly remember the last time I sat at a desk – I’ll probably be useless. Don’t you miss your job?’ she managed to say after a moment.

Marjorie looked wistful. ‘I’d be lying if I said I didn’t. I had to fight tooth and nail to do my training. My family thought I was crazy, spending all that time studying for my Higher Cert and then going to college, when I’d only end up getting married and having to give up anyway.’ She shook her head. ‘Well, that’s not going to happen. I prefer teaching to going out with men and I’m not ashamed to say so. When this war ends I’ll be back in the classroom like a shot. But meanwhile I’ll do whatever’s needed here. It’s just a pity that happens to be scrubbing floors, or ferrying urgent messages backwards and forwards, never mind the endless PT lessons. I know we’ll have to be fit, but at the moment my muscles don’t know what’s hit them.’

‘Too true.’ Laura sloshed the water around in the bucket and went back to the task in hand. ‘You must have been really determined to get to college, Marjorie. I must say I envy you. I’d have loved to be allowed to study like my brother, but my folks wouldn’t hear of it. My father still thinks that women get ill if they have to think too hard. Doesn’t want me coming down with a fit of the vapours.’ She rubbed at the tiles. ‘There, that’s better. Do you think they’ve ever been so shiny?’ She sat back on her heels once more. ‘I probably shouldn’t say it, but if there’s anything good to come out of this war, then maybe it’s going to be people like us having the chance to find out what we’re good at and to get on and do it. I’ve always been terrible at sitting around in drawing rooms and making polite conversation. There must be more to life.’

Kitty giggled. ‘I’d have loved to be made to sit down and talk to people. We never had time for that.’ The very idea was completely opposite to what she’d known in her life so far. Perhaps that was no bad thing. She wanted to be fully prepared for whatever was going to happen to them next. If their future survival was going to depend on their physical fitness in any way, she wouldn’t complain about the seemingly pointless rounds of PT.

Marjorie looked at them both and smiled. ‘I was always too busy studying or marking to do much of that either. So what are you good at, Laura? Apart from your budding ability to clean a floor?’

Laura pushed up her sleeves again. ‘I, my dear, am good at having fun.’ She grinned mischievously. ‘Stick with me and I’ll show you how, you see if I don’t.’

Danny Callaghan sat at the kitchen table and felt the silence echoing around him. He couldn’t get used to it. He’d never experienced anything like it in this house – there had always been Kitty bustling around, Tommy bothering them both, and now and again Jack striding about and giving him advice, whether he wanted it or not. Then there had been all the friends and neighbours popping in and out, passing the time of day, sharing cups of tea. He could hardly believe it was the same place. There was the kettle still in its spot on the hob, there were the cups and saucers and plates, steadily getting more chipped, but there was no delicious smell of baking from when Kitty miraculously managed to procure the ingredients for one of her delicious cakes or pies, and no pile of scraps that Tommy had salvaged from a bomb site and brought home to keep in case they were useful.

He couldn’t stand the thought that everyone was out doing their bit for the war effort when he was confined like this. He wasn’t usually given to self-pity or despair, but if he allowed himself to think too far ahead he could feel all hope draining from him. He was young, he was enthusiastic, he didn’t know the meaning of fear, and yet all because of a ridiculous twist of fate he wasn’t allowed to fight for his country’s freedom. It hurt him bitterly.

Sighing, he drew the newspaper towards him. This was his one regular piece of routine: ever since coming out of hospital he had made himself do the crossword every day. He’d never seen the point of it before, but during the long, empty hours convalescing on the ward, a fellow patient had introduced him to the challenge of filling in the gaps, solving the complicated clues. He’d bonded with the older man and somehow their shared interest had overcome the difference in their backgrounds. It turned out that the man was a high-ranking officer, who’d now returned to some shadowy behind-the-scenes, hush-hush role, whereas of course Danny had never been able to join any of the armed services, thanks to his damaged heart. But for those few moments the two men had been united in tracking down the perfect solution, and Danny had been bitten by the crossword bug. He’d made himself do one a day ever since. It was strange in some ways. He’d been no slouch at school, but had been too restless ever to settle down and make the most of his studies. He knew he had a good brain but had preferred to use it coming up with the latest scheme to make money or have some fun while working on the docks. Now all that was denied him, for the immediate future anyway, he took refuge in the pastime of thinking for its own sake.

He was absorbed in what he thought must be an anagram when there was a knock at the door. He almost jumped, he’d been staring so intensely at the arrangement of letters, willing them to form a recognisable word. He shook himself and shouted ‘come in’, as the door opened anyway and Sarah Feeny stepped inside.

The youngest of the Feenys, Sarah shared the no-nonsense, get-up-and-go attitude of her mother. She’d taken to her VAD nurse training like a duck to water, despite being so young. There wasn’t much that shocked or surprised her – having all those older brothers and sisters meant she’d heard it all before. Now she looked about her and grinned. ‘Blimey, Danny, it’s as quiet as a church in here.’

‘Tell me about it.’ Danny made a face. ‘Cup of tea? The pot’s around somewhere.’

‘Oh, I can see it, I’ll do it,’ Sarah offered at once.

Danny rose. ‘I’m not dead yet, I can still make a pot of tea,’ he told her, more sharply than he’d intended.

Sarah’s face fell. ‘I didn’t mean it like that, you know I didn’t. I was just trying to be helpful.’

Danny groaned inwardly. He knew he was over-sensitive to everyone trying to molly-coddle him, and that’s why he hadn’t told anyone about his condition in the first place – anyone apart from Sarah, who’d found out. She was the last person he wanted to snap at and he felt bad about it, but that’s what came of spending too long on his own with only his puzzles for company.

‘I know,’ he said, his face softening. ‘But it’ll do me good to stretch my legs a bit. You make yourself comfortable, you must have been rushing round all day. Take the weight off your feet, I’ll only be half a mo.’

Sarah sank gratefully into the chair that until recently had been Kitty’s. ‘It’s so nice to have a bit of peace! No, don’t look like that, I mean it. People have been shouting at me all day at work and my head’s fit to burst with all the things I’m meant to remember. Then I come home and there isn’t a spare inch of space. Nancy’s in a mad flap because Gloria’s coming back for a visit and she hasn’t got anything to wear if they go out. Rita’s there because Mrs Kennedy’s driving her round the bend. Violet’s going on and on about the victory garden – you’d think she’d been a farmer or something before she married Eddy. Mam’s got piles of old rags everywhere, which she says are for her make-do-and-mend classes. Mam and Pop are bickering like they always do. It’s like a madhouse.’ Her hand flew to her mouth. ‘Oh, don’t listen to me, I don’t mean it. I love them all, you know that. But sometimes it gets to me, I can’t help it.’

Danny smiled. ‘A bit of a contrast to here, which is like a monastery. You’re doing me a favour keeping me from going crackers rattling around here on my own.’

Sarah beamed. ‘Good, I’ll put my feet up then. Don’t suppose you’ve got any sugar? I know we aren’t supposed to have any in our tea now as it’s not patriotic, but some days it’s the only thing that’ll keep me going.’

Danny turned to the corner cupboard. ‘Don’t tell anyone, but I’ve got a secret stash of it in here. What’s the point of working on the docks if you can’t sweeten your tea now and again?’ He passed it across. ‘Just don’t make a habit of it, all right – it might have to last for the rest of the war, however long that’ll be. My contacts aren’t what they were, not since the fire.’ He smiled ruefully.

‘Don’t worry, this is a treat,’ said Sarah, stirring the precious sugar into her drink. ‘I’m not encouraging you to go on the black market, Danny. Not like that Mrs Kennedy, we all know what used to go on in her shop.’

‘Used to?’

Sarah looked up at him, registering how pale he looked, his face white in contrast to his dark wavy hair. ‘You haven’t been in there recently, then? It’s driving Rita mad. Winnie’s hardly ever behind the counter, Rita’s left to open up and shut the shop, and it’s hardly making any money any more. She never has a moment to think straight, let alone visit the children. I think missing Michael and Megan is making it worse.’

‘But they’re happy on the farm, aren’t they?’ asked Danny. ‘Our Tommy’s having the time of his life. Or so I gather from his letters. His handwriting isn’t the greatest, but he goes on and on about the animals, they’re turning him into a right farmer. At least he’s making himself useful digging for victory. He loves it, so I bet the others do too.’

‘It’s not that so much as being apart from them,’ said Sarah. ‘Honestly, Danny, they’re all fine. Rita showed me one of Michael’s letters – they couldn’t be in a better place. But she misses them like mad, even though she knows they’re safer there than just about anywhere.’

‘Can’t she go and see them?’ asked Danny, then cursed himself for his own stupidity. What had Sarah just told him? The shop wasn’t making money and Rita had hardly any spare time. Of course she couldn’t just up sticks and catch a bus out to the country – always supposing there were buses running anyway.

Sarah shrugged. ‘You know it’s not that easy. Pop would take her in his cart but he’s never home either – he’s on ARP duty all the time. When he isn’t, he’s sleeping off the night shifts. You know how it is.’

Danny nodded. He remembered all too well the effects of working night shifts. Your brain didn’t feel as if it was your own. Then the idea struck him.

‘Why don’t I take her?’

‘Well, I’m sure it would be a lovely thing to do but …’ she began.

‘No buts,’ said Danny, suddenly seeing that this was the ideal solution. ‘Come on, Sar, it’ll be doing me a favour. I get to leave the house, but I’ll be sitting down the whole time so won’t need to worry about me ticker – while Rita gets an escort to see the kids. I get to see Tommy, check he hasn’t run too wild. Everyone wins.’ He stood up.

‘Danny, what are you doing?’ Sarah set down her mug.

‘Well, you just said they’re all there. We’ll go and tell them now. No time like the present.’ And before she could stop him, Danny headed out of the door, a new spring in his step.

CHAPTER SEVEN

‘Now are you sure you’ll be all right?’ Rita was torn between wanting to get going as soon as possible and anxiety that her sister-in-law wouldn’t be able to manage. She hastily buttoned her coat against the chilly spring breeze blowing through the open shop door.

‘Of course!’ Violet assured her. ‘Don’t even give it a thought, I’ll be absolutely fine. What can go wrong? You get off and see those children. There’s Danny now with the cart. Go on, stop mithering, I’ll see you later.’ She all but pushed Rita out of the door.

Rita hopped up on the cart beside Danny, tucking a loose strand of red hair behind her ear. ‘If there are any problems just make a note and I’ll sort everything out later,’ she called. She waved as Danny lifted the reins and the horse began the steady clip-clop that would take her to her beloved children.

Violet waved back cheerfully but gave a sigh of relief as she shut the shop door. She was sure that she could cope, but somehow not having Rita around made her feel more worried than she expected. She glanced around the place. Rita had dealt with the early morning rush, when the dock workers came in to get their newspapers, cigarettes and other essentials, and now everything was quiet. This was when Winnie would normally take over, but she’d gone back to her bed in a huff once she learnt that Violet had been drafted in to help, muttering what were most probably insults as she retreated up the stairs. Violet could have sworn the older woman had been unsteady on her feet, her eyes red, but she wasn’t going to dwell on it. She’d rather face a day in the shop on her own than share the cramped space with Winnie, who in their short acquaintance had been nothing but unpleasant. Still, she wasn’t going to let that upset her; according to Rita and Dolly, the miserable old bag was like that to everyone.

Violet decided the shelves could do with a clean. Poor Rita, she must never have the time to do it, so this would be something she’d appreciate. Violet wasn’t scared of hard work and elbow grease and she soon had the surfaces gleaming. Beaming, she looked around in satisfaction. That was a big improvement. Working in a shop was a doddle, she decided, as she put her duster behind the counter and smoothed down the front of her printed overall. Rita had been fussing about nothing.

No sooner had she settled herself on the stool behind the counter than the bell rang and a plump figure in a plaid headscarf came in. Violet recognised Mrs Mawdsley, a friend of Dolly’s from the WVS. She was a bit of a dragon when you first met her but nice underneath.

‘Oh, it’s you, dear!’ Mrs Mawdsley peered short-sightedly over her round glasses. ‘I didn’t expect to see you here. Has there been an emergency? I do hope everyone’s all right …’

‘Nothing to worry about, Mrs Mawdsley,’ Violet said hurriedly, cutting off her customer before she could work herself into a tizz. ‘Rita’s gone to see her children for the day and so I’m standing in. How can I help you?’

The older woman undid her scarf and came closer. ‘Well, that’s very good of you, dear. That’s what families are for, though, isn’t it? I won’t keep you for long. I’m looking for some clothes pegs.’

Violet smiled in relief. ‘Well, you won’t need ration coupons for those.’ She’d been slightly confused by Rita’s explanation of which goods were rationed and which weren’t, and how the system worked, but this request should be simple enough. ‘Household goods are on these shelves here – but I expect you know that better than I do.’

Mrs Mawdsley beamed at the suggestion she knew her way around the shop better than the staff. ‘I do indeed, dear. Oh, someone’s made this look nice. Was that you? Dolly’s always saying what an asset you are around the house, and I expect Mrs Kennedy will be delighted.’

Violet smiled back but said nothing. She doubted Winnie would be delighted about anything.

‘Here we are, then. I’ll have two sets, a small and a large, just in case.’ The woman fiddled with her purse. ‘Now, I’m afraid I have no change, but I hope that won’t be a problem.’

‘Of course not.’ Violet held out her hand and Mrs Mawdsley gave her half a crown. Violet’s smile began to falter. Mental arithmetic was not her strong point. It was bad enough that there were two things to add up, but they were at different prices, and that made it more difficult. She looked around for a notebook. Maybe if she wrote it down it would be easier.

The doorbell rang again. A frail old lady stepped inside, drawing her shawl around her thin shoulders. ‘Hello, Mrs Mawdsley,’ she said in a tremulous voice. ‘And … it’s not Rita, is it? No, I can see you have different hair, young lady. My memory’s not what it was, you’ll have to—’

‘It’s Violet, Mrs Ashby,’ said Violet, recognising the oldest inhabitant of Empire Street. ‘I married Eddy Feeny, you know. Haven’t seen you since we were in the shelter together for the last air raid.’

‘That’s it!’ The old lady’s face lit up. ‘So you’re helping out here, are you? I’m glad to see you. Now maybe you can help me with my sugar ration. I like it when Rita does it, she’s always very fair, but sometimes,’ she dropped her voice, ‘Mrs Kennedy gets it a bit wrong and there never seems to be enough in the packet.’ She reached into her battered handbag.

‘Don’t you fret, Mrs Ashby, I’ll see you right,’ Violet assured her. ‘Let me see, I know the stamp for the coupons is back here somewhere …’

Mrs Mawdsley leant across the counter and tapped the front of a small drawer. ‘In here, dear. I think you’ll find that’s where it usually is.’

‘Oh yes, that’s the place, Rita did show me.’ Violet was getting really flustered now. ‘So, you give me your coupon …’

‘But I just did, dear.’ Mrs Ashby’s voice shook a little but she was adamant. ‘One moment ago. You’ve taken it already.’

Violet clapped her hand to her forehead. ‘Silly me. What am I like? Yes, you gave me the coupon, now where …’

‘It’s by the till where you put it,’ Mrs Mawdsley explained. ‘Right next to my half-crown. You’ve still got to give me my change.’