Полная версия:

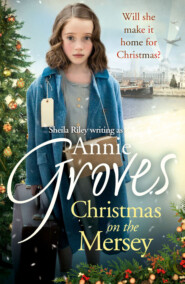

Christmas on the Mersey

Christmas on the Mersey

Annie Groves

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2014

Copyright © Annie Groves 2014

Cover photographs © Colin Thomas (girl, woman); Charles Bowman/Getty Images (buildings); Shutterstock.com (all other images)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Annie Groves asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007550821

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007550838

Version: 2017-09-12

Dedication

To the memory of my wonderful Mum and Dad

(You always believed in me xxx)

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Keep Reading: CHILD OF THE MERSEY

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Annie Groves

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

October 1940

‘The patients who are too ill to be moved will have to go under the beds!’ Sister Rita Kennedy said as she hurried down the long ward, clearing it of patients who could be moved to the basement. The Germans had been dropping bombs almost every night since August. Now they were targeting the docks, so close to the hospital that Sister Kennedy imagined the pilots could probably smell the antiseptic they cleaned the floors with.

Many of the patients had been moved to hospitals in safer locations months ago. This hospital, close to the vital supply line, was a prime target. Everybody around here knew that to put the docks out of operation would be seen as a major coup for Germany. These remaining patients were emergency cases, brought in for assessment or emergency surgery before being sent elsewhere. The ward was busy every day, but since the raid started, only moments ago, it was like Lime Street Station at rush hour.

‘Johnny the porter said an enemy plane has been shot down over Gladstone Dock!’ Sister Kennedy did not have to listen too carefully to hear the probationer nurse’s excited words. ‘He said the pilot has landed in the Mersey.’ Sister Kennedy, like everybody else in this hospital, had friends and family who were serving, but this was neither the time nor the place to gloat.

‘They say he’s still alive and they’ve sent a crew to seize him!’

‘Do you think they’ll bring him here?’ another nurse enquired as they helped an old woman from her bed. The sound of anti-aircraft fire almost drowned out her question.

‘There’s no time for idle gossip, just get on with making the patients as safe as you can, please.’ Twenty-five-year-old Rita’s nerves were raw; her own children, just a few minutes’ walk away from the dockside hospital, had been brought back from the farm to which they were once evacuated. They were so happy there, Rita knew, but now they were in as much danger as everybody else.

‘Let’s not frighten the patients with supposition, Nurse,’ Rita whispered, and the young nurse nodded.

Promoted to ward sister just last week, Rita had no intention of voicing or showing her fears to the junior nurses. Panic could spread, she knew, and keeping a cool head was vital. Hitler’s Luftwaffe had so far failed to invade Britain by defeating the RAF in the skies over the South-East, but there was no let-up in their attempts, and they were now attacking the industrial cities and ports across the country. Rita pushed down on her growing anxiety. Why had she insisted on bringing the children home from the safety of their countryside billet near Southport?

There were so many of her family to worry about, too. Rita said a quick, silent prayer for her brother Eddy. He was sailing with the convoys in the North Atlantic, bringing back vital food and supplies. He told her, when he was home last time, that the wild, impetuous ocean could be a terrifying place for the most experienced sailor, and that was without torpedoes firing at them. Now Rita thought she knew a little of what he was going through.

‘That’s enough chattering.’ Rita, impatient now, worried that the two young nurses, still speculating about the shot-down German bomber, were not moving fast enough. ‘You know what they say about loose lips!’ This hospital would be the first place to bring the injured aviator – even if he was an enemy pilot. However, they were not here to judge but to ease the suffering of every patient brought through the double doors of the hospital, no matter what his nationality. ‘Go to it!’

‘Yes, Sister,’ the junior nurses chorused and resumed their duties. Rita kept half an ear on the drone of enemy aircraft as she made her patients safe, her practised demeanour professional and efficient. Internally, however, her terrified thoughts were with her children, Michael and Megan.

Please, Lord, make them safe, she prayed silently. Don’t let anything happen to my babies.

Michael and Megan would now be huddled in the corner of the cellar beneath the shop where Rita lived with her husband, Charlie, and his poisonous mother, Winnie Kennedy, who owned and ran the corner store. The cellar was where she stored her stock and they should be safe down there. Rita wished that she were there with them, but when the country was crying out for nurses, how could she duck her duty, especially after the fall of France last June? The enemy was only just across the Channel.

‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph!’ Nurse Maeve Kerrigan said. ‘Sounds like all hell is breaking loose out there.’ Rita and Maeve had been firm friends since they started work at Bootle Infirmary on the same day. Maeve had been a cheeky upstart but her sense of humour and ability to keep everyone’s spirits up had built bridges with Matron, and the patients all adored her. Maeve quickly took in Rita’s furrowed brow.

‘I can imagine what’s going through your head. But the ould battle-axe will manage your two young snappers,’ she said quietly, so as no one would overhear. ‘She might be a witch, but she’s still their granny.’

‘But she’s not their mother.’ Rita knew her friend was trying to calm her as they eased a post-operative patient into a wheelchair. ‘I’ll never forgive myself if anything—’

‘Enough of that,’ Maeve whispered. ‘You’ll drive yourself demented if you carry on thinking that way.’

Rita nodded, turning to help another patient into his dressing gown. It was impossible not to be burdened with maternal guilt. If one hair on either of their heads was hurt …

‘Anyway, if the Germans did land, you could hand her over first. They’d swim back over the Channel faster than you can say “Jack Robinson” once they got an earful of her bile. She’d make up a whole new front!’ Maeve added in that crisp Irish tone that could change from angelic to raucous in the blink of an eye.

‘Come on, let’s get the patients out of here.’ Rita pulled herself together and took a deep breath to calm her racing heart; there were thousands of mothers going through the same thing all over England. She had her patients to think about now.

The almost deafening sound of an explosion close by made the medical staff move even faster.

Michael and Megan would be terrified. The thought made Rita blanch. Her skin was now clammy. It would be her fault if anything happened to her children. She was the one who had persuaded Charlie to let her bring them home from the farm when there were no signs of air raids or invasion, something the newspapers called ‘the phoney war’. Charlie had said Michael and Megan were safer in the countryside, but after Rita’s repeated begging, he had reluctantly agreed to let them come home. However, now Rita was certain she had done the wrong thing – Empire Street, right by the docks, was one of the most dangerous places in the world.

Please Lord, Rita sent another silent prayer to heaven as she moved the patients, please keep my children safe.

Rita could recall with clarity the look on Charlie’s face seven and a half years ago when he held Michael for the first time. Sometimes, Rita could still feel the crippling remorse that she experienced then, but now it was for a different reason. Now her remorse was for the choices she had made and for the life she would never have. Any guilt she had left was for her children and her inability to give them a happy home life and an adoring father. Her husband had proved himself to be a liar, a cheat and a brute.

However, this was not the time for thinking such things, she acknowledged as another barrage of anti-aircraft fire stalled further thoughts. Right now her priority was the safety of her patients.

The blast from nearby incendiaries shuddered through the building and Rita fought the urge to duck under the nearest bed, instead calling for the nurses to remain calm and go about their work as quickly as they could. She thought she had moved all the patients from along the far wall where splintered glass from a whole row of shattered windows jettisoned onto the ward, causing the blinds to flap like startled blackbirds in the chilly, damp night air. To her horror, however, Rita could now see that Albert Scott, a kindly old man who had taken a nasty fall during one of the recent raids and had broken his hip, was still in his bed near the window and urgently needed moving into the middle of the ward.

‘Don’t worry, Bert, I’m on my way,’ she called as she ran across, careful to sidestep the broken glass that littered the whole floor. The deafening roar of exploding bombs and anti-aircraft fire coming through the windows was disconcerting, but Rita could see that the ward was a sitting duck for the bombers with the blown-out windows and blackout curtains torn to shreds.

‘Turn those lights off!’ she yelled, and the room switched to sudden blackness, lit only by the fires that blazed outside and the searchlights directing the ack-ack gunfire.

‘Are you all right, Bert?’ she asked, taking the old man’s hand.

He gripped hers tightly, but his voice, though weak, was determined. ‘Don’t you be worrying about me, love. I saw worse than this in the trenches. Jerry didn’t get me then, and he won’t get me now.’

‘You tell ’em, Bert.’ She squeezed his hand. ‘Now bear with me while I just try and get you a bit more comfortable. Maeve, come here and give me a hand with this.’

Rita shook broken glass from the blankets, then asked Maeve to help her manoeuvre a heavy mattress from one of the empty beds over Bert, who could not move from his own. But the mattress was covered with shards of broken glass and Rita had underestimated the weight of it. It took the combined strength of both women to lift it off. As they did, there was another ear-splitting scream overhead and then another blast shook the building, loosening more glass from the damaged windows.

‘For God’s sake, get down!’ Rita screamed, and Maeve fell to the floor and crawled beneath one of the beds, while Rita desperately tried to cushion herself and Bert with the mattress. The bombardment continued for several more minutes though it seemed to Rita to last for hours.

Once the planes had dropped their deadly load and passed over, Rita lifted her head and saw to her horror that it was too late. She had managed to shield Bert from the worst of the falling glass and masonry, but it had all been too much for him and she thought that his heart had given out. He lay still, his eyes glassy and empty. ‘He’s dead. The bastards!’ Maeve swore to the sky. Rita did not admonish Maeve – she felt exactly the same way – but she urged Maeve to keep her voice down so as not to scare the other patients.

‘Oh, Bert,’ Rita whispered, looking sadly down at the dead man. Gently she touched his pale and wrinkled hand. ‘He’d already been through so much.’

Rita felt the sting of tears behind her eyes but she knew there was no time for indulging her emotions. The all clear was sounding and she had to organise the clear-up.

‘Right, everyone, we need to get the ARP to help us board up these windows and get all of this glass up. Don’t be tempted to clean it up yourselves; you’re likely to be cut to shreds.’

Over the next few hours, Rita even had the staff singing to keep up morale as they moved the patients back to bed and continued the clean-up. Eventually, the glass was cleared and they were busy boarding up the windows.

After welcome cups of cocoa and slices of freshly made toast were given to the shaken-up patients, the nurses themselves were able to take a breather and headed for their own cups of cocoa in the small kitchen at the end of the ward. It is a wonder no other patients were harmed tonight, Rita thought. The dead man was taken to the morgue while she said a silent prayer of thanks that everybody else had come through the awful barrage unscathed.

Tired but keen to get home at the end of her shift, she hurried down the long corridor. The cabbage-green tiled walls felt as if they were closing in on her now. She was desperate to get home to see her children.

Picking up a daily newspaper on her way home, Rita was eager for any news of the war at sea. She was the eldest of Pop and Dolly Kennedy’s five children. Frank, a petty officer in the Royal Navy, had frightened the living daylights out of everyone when he had lost a leg after his ship was torpedoed. He was making a good recovery but Rita knew that the scars ran deep. Her younger brother, Eddy, the merchant seaman, was in great danger of falling victim to German U-boats in the North Atlantic convoys. Front-line warriors, Pop called them, although it was the air battles that still seemed to dominate the news. Not surprising after the Royal Air Force had successfully defended the skies of the South-East in the conflict Mr Churchill called the Battle of Britain. Rita’s younger sister, Sarah, was also doing her bit by training to be a Red Cross nurse.

Reading between the lines of the news reports, it was hard to get a handle on the real story. The paper was full of the victories of Fighter Command, but Pop said that the papers weren’t allowed to be honest about the real losses as it would be bad for morale. But there was no doubt that the RAF had carried out a heroic defence of the country and that ordinary people had so much to be thankful for. It was far from over, however. Day after day, the Luftwaffe continued their deadly assaults on the larger cities all over the country. There was no hiding the reality of the destructive power of the German air raids. Fighter Command were under extreme pressure, the newspaper said.

‘Don’t we know it,’ Rita said aloud, aware that people in this part of the country were as much in the front line as the soldiers and the fighter pilots. It was not just the men like Eddy that risked their lives, but also those who loaded and unloaded the ships that ferried the necessities of war and civilian life. They too were the target of the Luftwaffe.

Rita now knew the truth of the rumour that a young German pilot had been brought in injured. She pushed down the hope that he was suffering as much as Frank, whose leg had had to be amputated below the knee after infection had set in. She also tried to rid her mind of the fact that the German may know others who would try to blow up the supply ship on which Eddy served, and which had to run the gauntlet of torpedoes and mines every single day. Yes, she was ashamed of feeling that way; it was unchristian as well as cruel. But when she thought again of Bert’s lifeless body, she couldn’t help herself.

‘Mammy!’ Michael and Megan shot up from the breakfast table to greet their mother, and Rita’s heart sang with joy and relief.

‘Oh, thank God you are safe!’ She scooped her children into her arms, thankful beyond words that they were unharmed.

‘Mammy, we could hear the German planes dropping their bombs. It was so exciting – can I go out and look at the flattened houses?’ Rita looked in amazement at Michael. His eyes were shining with excitement and for a moment she could almost feel what it must be like to be a seven-year-old boy living through these interesting times. But then her anxiety kicked in again and she prayed that she would not have to go through another night of worry as she had last night, knowing there was little she could do about it now the hospital needed her. But her children needed her too. How many other women were feeling like she did this morning, she wondered, torn between her nursing duty and a mother’s fear? Rita felt absolutely wretched at the thought of another night away from them.

‘You’ll do no such thing,’ she admonished gently, ruffling her son’s hair as he chattered away nineteen to the dozen. Rita felt a little hand squeeze her own and looked down to see the pale face of Megan. Unlike Michael, she was quiet and clingy. Rita hugged Megan to her and felt her heart wrench at how frightened the little girl must have been without her.

‘Small thanks to you, they are fine.’

Charlie’s barbed words caused that familiar feeling of guilt to rise up in Rita’s heart as he entered the small breakfast room, his mother – making a great play of her bad leg – following behind. Rita looked at him. He was lean and once upon a time she had thought him handsome, but now his hair was thinning and his face always bore a sneer, or his words a put-down. Sometimes she could barely bring herself to look at him. Now his icy glare seized her and held her in its grasp. Rita knew that trouble had been brewing and she steeled herself for his onslaught.

‘What kind of a mother leaves her children during an air raid?’ Charlie’s voice was laced with malice as he addressed his mother, who nodded in agreement.

Ma Kennedy had assumed her usual seat by the window. She was wearing her housecoat and had her hair in curlers, covered by a headscarf. Her face wore the sour look of disapproval that Rita had come to know so well.

‘I know Charles, it is unforgivable! You have an obligation to your family, Rita!’ Mrs Kennedy’s mouth puckered and her condescending expression told Rita she thought she wasn’t much of a mother if she could not be here for her own children during an air raid.

Rita felt that she had little room for manoeuvre when they ganged up on her like this. These days she usually put up a strong resistance, but her own guilt and anxiety were threatening to gang up on her too. She felt weak, tired and unable to defend herself. She should have been here. Of course, she should.

‘You both know that hospitals all over the land are in dire need of trained staff. People like me are in short supply,’ she countered weakly.

‘People like you?’ Charlie sneered. ‘Listen to Rita, Mother! Looks like she’s going to save the country single-handed. Shame she doesn’t feel as strongly about her own kids.’

Rita felt her stomach dip.

‘You’ll have to tell her, Charles.’ His mother was standing now, poker stiff at the side of the table while Rita, feeling as bad as it was possible for a mother to feel, none the less did not fail to notice the sidelong, warning glance Charlie gave his mother.

‘Mind your own business, can’t you?’ His tone now turned to impatience as he barked at the children, ‘Michael, take Megan through next door to the lounge and put the wireless on.’

The children both looked at Rita uncertainly, but she nodded for them to go. It wouldn’t do for them to get caught up in a row.

‘Tell me what?’ Rita’s throat tightened and she found it difficult to swallow, her mouth now paper dry with trepidation.

‘The children are being evacuated today – this morning,’ Charlie said without preamble. ‘It’s all arranged – and don’t even think about trying to stop it.’ He did not hang around long enough for Rita to answer but stalked from the room. She could hear him taking the stairs two at a time.

Rita was confused. What did he mean, they were going to be evacuated today? Where to? They’d been back home for only a few months. She scraped back the chair and stood up, but before she left the room she laid her hands flat upon the table and leaned towards Mrs Kennedy.

‘Did you know about this?’ She knew her husband couldn’t organise the children’s evacuation on his own. He would not have the foggiest idea where to start.

Ma Kennedy folded her arms and looked away. ‘I’m saying nothing,’ was all she offered.

Rita pushed down her anger at her mother-in-law and headed for the stairs at a run. She opened Megan’s bedroom door to find Charlie there, and her heart lurched. There were two suitcases on the bed, one for each of her children, and he was folding Megan’s clothes into hers.

‘Are you sending them back to Freshfield Farm?’ It had been so harrowing when they were evacuated last time, billeted on a farm way outside the city. The people that had looked after the children were decent folk and the children were happy. Rita knew that they had been well looked after. If they had to go away again, it would break her heart, but she also knew that the children were no longer safe. Charlie was right.

‘No. I’ve made other arrangements.’

Cold fear ran through Rita’s veins as she heard these words and her voice shook. ‘What other arrangements? What do you mean? Tell me!’

‘Get a grip of yourself, woman.’ Charlie’s voice was full of scorn. ‘I’ve got a place lined up …’

‘Where?’ Rita asked.

At first he said nothing, ignoring her as he put a few more items into Megan’s suitcase, which had been neatly packed. Charlie never lifted a finger around the house and would have as much idea about packing a suitcase as flying a Spitfire. His mother must have helped him. He stopped what he was doing and straightened up, his expression full of contempt for her.

‘I know of a little boarding house in Southport.’

‘How?’ Rita asked. ‘We don’t have any family there.’

‘It’s run by an old lady Mother knows, Elsie Lowe …’ Charlie looked away again and shut the lid of Michael’s suitcase.

‘Is this your mother’s doing? She’s never liked the children being here. This would be her way of getting them out from under her feet …’