Полная версия:

A Mother’s Blessing

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain as Goodnight Sweetheart HarperCollinsPublishers 2006

This edition published 2020

Copyright © Annie Groves 2006

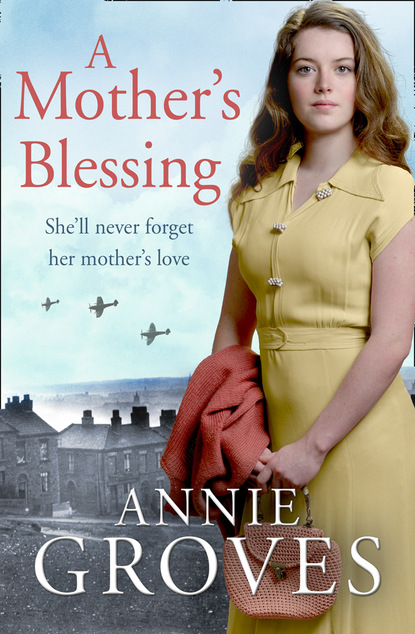

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

Cover photographs © Gordon Crabbe (model), Daily Herald Archive / Getty Images (background)

Annie Groves asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008395872

Ebook Edition © January 2009 ISBN: 9780007279500

Version: 2020-01-30

Dedication

For Maxine – confidence-builder extraordinaire

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: July 1939

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Part Two: Christmas 1939

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Part Three: October 1940

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About Annie Groves

Also by Annie Groves

About the Publisher

ONE

‘No! Don’t.’

‘Aw, what’s up with yer?’

‘It’s not right, that’s what,’ Molly announced, keeping her arms folded tightly over her chest to prevent Johnny from making a fresh attempt to touch her breasts. It was a warm July evening and they had decided to walk home from the cinema on Lime Street to Edge Hill, the small tight-knit community of streets clustered together in a part of the Liverpool that didn’t belong to the dockside but wasn’t part of the new garden suburbs like Wavertree either. A few yards ahead of them, she could see June, Molly’s elder sister, locked in the arms of her fiancé, Frank.

‘Aw, come on, Molly, just one kiss,’ Johnny persisted cajolingly. ‘Look at your June. She knows how to treat a chap.’

Molly didn’t really want to look at June because June was with Frank, and just thinking about her sister’s boyfriend always made Molly’s heart ache painfully and her skin flush. But Frank was June’s. And the only smiles he ever gave to Molly were kind and older-brotherly. Agreeing to go out with Johnny was the best way Molly could think of to stop herself from thinking about Frank. Frank belonged to June, and that was that.

‘Come on, Molly, give us a kiss,’ Johnny coaxed. ‘There’s nowt wrong in it. Look at your June and Frank.’

Molly tensed. There it was again – that pain she had no right to have. She had been struggling all evening to evade Johnny’s amorous advances, and the eagerness she could hear in his voice now, as he pressed closer to her, made her feel wretchedly miserable and uncomfortable. What was wrong with her? Johnny was a good-looking lad, tall with thick dark hair. But his bold gaze and knowing smile intimidated Molly. Instinctively, she knew that Frank would not make a girl feel uncomfortable when she was with him; neither would he start pressing her for intimacies she wasn’t ready to give. Unhappiness clogged her throat and tears burned at the back of her eyes.

June and Frank were oblivious to Molly’s plight. Not that June would have had much sympathy with her, Molly knew. It was June who had insisted on her going out with Johnny in the first place – he was a friend of Frank’s and an evening out all together meant June could see Frank and keep an eye on her younger sister at the same time. Like every girl in the country who was walking out with a lad who had just received his call-up papers for the now obligatory six months’ military training, June was anxious to spend time with Frank whilst she still could.

‘June and Frank are engaged,’ was all Molly could think of to say to Johnny to justify her own refusal, her voice slightly breathless as she wriggled away from his embrace.

‘Well, me and you are as good as – leastways we would be if I had me way,’ Johnny told her.

She stared at him with a mixture of dismay and shock. ‘You can’t say that,’ she objected. ‘We aren’t even walking out proper. And besides …’ She looked towards her sister and Frank.

‘Besides what?’ Johnny too turned to look at the other couple, then said sharply, ‘You spend that much time looking at your June’s Frank, you’ll have me thinking you’d rather it were him you were with than me.’

‘Don’t be silly. Frank’s engaged to our June.’ Her heart was pounding now and her face was starting to burn. Her hands felt hot and sticky.

‘Aye, and you could be engaged to me, if you was to play your cards right,’ Johnny told her meaningfully, moving closer. ‘Especially now that I’ve had me papers, and me and Frank have to report for training on Monday.’

To Molly’s relief the other two had stopped spooning and her sister was turning round to face them.

‘What’s up with you, our Molly?’ June demanded when Molly and Johnny had caught up with them. ‘You’ve got a face on you like a wet bank holiday.’

‘Aye, that’s what I’d like to know, an’ all,’ Johnny joined in, ‘seein’ as how I’ve just been telling her I want us to be engaged.’

‘What? You’re engaged!’ June shrieked excitedly.

As usual, June had got carried away and heard only the words she wanted to. Molly groaned inwardly. Now she would really have a job saying no to Johnny.

‘Here, Frank, did you hear that? Our Molly and Johnny have just got themselves engaged. Course, me and Molly know that it’s our duty to do everything we can to keep you soldiers happy.’ She giggled, but her face started to crumple as she added, ‘I was just saying to Frank that him and me should perhaps think about getting married sooner rather than later now that it looks certain there’s going to be a war.’

‘Now don’t go getting yourself upset, June. We don’t know that for sure yet,’ Frank protested.

‘Course we do. Haven’t you seen them leaflets the Government has sent out to everyone?’ she asked him scornfully, before turning to Molly and demanding, ‘Here, Molly, give us it. You did put it in your handbag like I told you to, didn’t you? We’ll have to have it with us when we go to work on Monday, so as we can tell old Harding that we’re going to need time off to go down to Lewis’s and buy that blackout material it says we have to have.’

Molly nodded and obediently opened her bag to remove the notice. She could hardly bear to touch it, let alone read it again. When it had dropped onto the doormat of the little terraced home they shared with their father, she had been innocent of the realities of war. The leaflet’s warnings about air raids, gas masks, lighting restrictions and evacuation alarmed her no end. She couldn’t believe that the familiar streets of her beloved home town might one day be poisoned by gas or blasted by bombs. She could only hope that the Government were being overly cautious and that the war – if it even happened – would be short and not affect the city …

‘See?’ June had triumphantly finished reading the leaflet aloud to the men, jolting Molly back to the present.

‘Well, we still don’t know for sure,’ Frank insisted, ‘but if there is going to be a war, mind, Hitler won’t be able to keep them tanks of his rolling against the British Army. Proper professional soldiers we’ve got,’ he told them proudly.

‘Oooh, Frank, don’t say any more. You’re making me feel right upset,’ June protested tearfully, her earlier glee at being in the know having evaporated, whilst Molly shivered at her sister’s side despite the warmth of the evening.

Everyone had been talking about war for so long without anything happening that it was hard to believe that anything was going to happen, despite the fact that the Government had already put in hand so many preparations. But its threat still hung over them like the dark rumbling shadow of distant thunderclouds. It was on everyone’s minds and everyone’s lips – a tension and anxious expectation that no one could ignore.

‘Well, we’d better get ourselves home and tell our dad that you’re an engaged woman now, Molly,’ June insisted, rallying herself.

‘That she is,’ Johnny grinned, taking hold of Molly and hugging her so tightly that it hurt as he pressed a hot hard kiss on her mouth.

Molly’s eyes stung with tears. She didn’t think she really wanted to be engaged to Johnny, but of course it was too late to say so now. He was fun and so handsome, and she knew she should be happy instead of miserable. It made her feel guilty to think that she didn’t want to be engaged to Johnny when he was going off to war. Besides, she could see how pleased June was. All her life Molly had done what her older sister had told her to do.

There were two years between them, and Molly could hardly remember the mother who had died when she was seven years old, other than as an invalid.

She could remember, though, lying in bed at night and listening to her mother cough. She could remember too the low anxious voices of Elsie from next door and the other women from the street when they came round to visit the invalid and do what they could to help. In the last weeks of their mother’s life, Elsie had come round every day, bringing home-made soup for their mother and some of her elderberry wine for their father. But in the end her mother’s illness had proved too much.

Their father had been devoted to their mother, and Molly knew how much he loved both his daughters. She and June were lucky to have such a good parent, and she was lucky, too, to have June as her sister. June had always been there for her, through good and bad, and Molly loved her deeply, even though she knew that other people sometimes found her sister a bit too know-it-all and bossy.

The four of them crossed the road, Johnny making a grab for Molly’s hand as they did so, and then turned into the street that would eventually take them into Chestnut Close, the cul-de-sac of redbrick terraced and small semidetached houses, where the two girls and Frank lived.

‘Dad will be wondering where we are,’ Molly urged the others on, fearing that Johnny’s sudden lagging behind meant that he was going to attempt to kiss her again.

‘Don’t be daft. He’ll be down at the allotments,’ June corrected her.

Their father, like many men in that community, rented a small allotment. It backed onto the railway line, and there he grew carrots, potatoes, turnips and peas as well as lettuce and tomatoes for salads.

In the summer months the men virtually camped out there to take advantage of the long days, often sleeping in the small wooden huts they had put up, boiling up billycans of tea on Primus stoves and eating sandwiches packed up by their long-suffering wives. And now, of course, the Government was encouraging them to do so. Every spare bit of land was to be turned over to the production of food.

The house their father rented was not one of the larger semis, like Frank’s widowed mother’s, but a small terrace, down at the bottom of the cul-de-sac. The bedroom Molly and June had always shared was a bit cramped now that they were both grown up. June often complained that they needed more space, that the house was a bit old-fashioned and shabby, and their furniture had seen better days, but number 78 Chestnut Close was home and Molly wouldn’t have swapped it for a castle.

‘There’s your mam spying on us, Frank,’ June commented sourly as they walked past Frank’s home. Molly stole a glance at the pristine house; the net curtains definitely seemed to be twitching.

Molly felt a little bit sorry for Frank at times, what with his mother forever trying to tell him how to run his life, vehemently taking against his choice of wife-to-be, and June equally determined to return Frank’s mother’s hostility towards her, but he was an easy-going, big-hearted young man, a right softie, always ready to do others a good turn.

They had all grown up together, although Molly, at seventeen, was younger than the other three. They had shared so much together over the years – including the loss of a parent each. Both Frank’s mother and Johnny’s were widows, but whilst Frank’s mother had been left with a bit of money and a pension, and only one son to bring up, her Bert having been killed in the Great War, Johnny’s mother had been left with three children and no money, her husband having been killed when he had stepped out in front of a tram after drinking too much.

‘If yer dad’s down his allotment then why don’t me and Frank come in for a bit?’ Johnny suggested with a cheeky wink, much to Molly’s dismay. She didn’t want to have to endure any further intimacies with him. His kisses and wandering hands made her nervous.

To her relief, Frank shook his head.

‘We can’t do that, Johnny,’ he protested. ‘It wouldn’t be right. We don’t want to be giving our girls a bad name, do we?’

‘Oh, and what do you think you’d be doing that would give us a bad name, eh, Frank Brookes?’ June giggled teasingly. ‘Chance’d be a fine thing, especially with your mam always waiting up for you,’ she added grumpily. Brightening up, she continued, ‘Look, seeing as how our Molly and Johnny have just got themselves engaged, why don’t we go to Blackpool tomorrow and celebrate? I fancy going dancin’ and having a bit of a good time.’

‘It’s Sunday tomorrow,’ Frank reminded her, ‘and there won’t be enough time to get there and back after church.’

‘Well, we ought to do something,’ June protested, none too pleased at being denied her dancing.

‘I don’t mind if we don’t,’ Molly assured her. When the other three turned to look at her she coloured up and said quickly, ‘I mean … what with everyone talking about the war, perhaps we shouldn’t celebrate …’

They had reached number 78 now, where the girls lived, and were standing by the privet hedge that bordered the small front garden.

‘Oh, Frank …’ June’s bottom lip trembled, her high spirits suddenly evaporating. Her emotions had always been able to change like quicksilver, although Molly wondered if they wouldn’t all become as volatile if war did break out. ‘I wish you didn’t have to go, not so soon. I’ll be glad when you’ve finished with this military training, and you’re back home proper, like. I just hope we don’t have this war. But if we do, you’re not going off to fight without us being married first,’ she warned him fiercely.

‘I think we should have a word with the vicar tomorrow after church, and tell him that we want to be married as soon as we can, instead of waiting until next June. And I’ll have a word with Mr Barker, the rent collector, and ask him to let me know if anything comes empty.’

‘What’s to stop you moving in with Frank’s mam? She’s got plenty of spare room,’ Johnny asked June.

June tossed her head belligerently. ‘I want me own house, thank you very much, and that’s why … oh, Frank …’ There were tears in her eyes and Frank put his arm round her and tried to comfort her.

Tactfully, Molly looked away, but at the same time she moved as far from Johnny as she could, not wanting him to get any ideas. To her relief she saw their father coming up the road, his familiar limping gait caused by the loss of a leg in the Great War.

‘Dad …’ Ignoring Johnny, she hurried towards her father, slipping her arm through his when she eventually caught up with him.

Albert Dearden was fond of saying that it was just as well his two daughters took after their mother and not him, reminiscing about how his wife had been a real beauty, and how, with her lovely naturally curly dark brown hair and her smiling blue eyes, Rosie had won his heart the moment he had laid eyes on her.

‘Here, Dad,’ June told him excitedly. ‘You’ll never guess what. Our Molly’s only gone and got herself engaged to Johnny.’

‘Well now. What’s all this then, lass? You’re only seventeen, you know.’

‘There’s a war on, Mr Dearden, and me being called up for the militia and like as not being sent off to fight—’ Johnny began boastfully.

But Molly’s father shook his head and stopped him, saying grimly, ‘There’s no war been announced yet, lad, and let me tell you, when we were called up to fight, the first thing we thought of was our country, not about getting hitched and leaving some poor lass worrying herself sick about us.’

‘Aw, Dad, have a heart,’ June complained.

‘Perhaps we should wait,’ Molly started to say, relieved a way out was being offered to her – for the time being, at least.

But her father was smiling lovingly at her, and he shook his head again and said, warmly, ‘Nay, lass, I’ll not stand in the way of young love. But mind now, Johnny, my Molly is a respectable girl and there’s to be no messin’ about and getting her into any kind of trouble, and no marriage neither until she’s eighteen.’

Molly smiled wanly, in stark contrast to Johnny’s beaming grin. A year seemed a long way off but it would come round eventually and then she’d have no choice but to marry Johnny. The reality of being engaged to Johnny was so very different from the chaste daydreams of Frank she had blushed over in the privacy of her own thoughts. Frank, with his gentle understanding smile and brotherly kindness, made her feel so comfortable and so safe. She didn’t feel either comfortable or safe with Johnny.

‘What’s up with you?’ June demanded forthrightly later that evening as she and Molly prepared for bed. ‘Anyone would think you’d lost a shilling and found a farthing.’

Molly put down her hairbrush and turned to look at her elder sister. ‘The thing is, June, I’m not rightly sure I want to be engaged,’ she said miserably, too tongue-tied to be able to explain just how confused and worried Johnny’s constant urgings to allow him more intimacy were making her feel. Even with sisters as close as they were, it was unthinkable that she should tell June how little she enjoyed Johnny’s kisses and how alarmed and uneasy they made her feel. June was so lucky to have Frank. Molly could see there was a world of difference in the way Frank treated June and the way Johnny kept on trying to pressure her.

‘Don’t be daft. Of course you do. And besides, you can’t change your mind now. That would be a shocking thing to do with him about to go off and fight. Anyone can see that he’s mad for you, and hundreds of girls would kill to be engaged to someone as good-looking as Johnny. He looks like a matinée idol, he does. But you be careful and play your cards right, our Molly, and make sure you don’t go giving him nothing he shouldn’t be having until after you’ve got his ring on your finger,’ June warned her darkly. ‘Frank’s mam looks down on us enough, without you getting me a bad reputation by getting yourself in the family way before you’ve got a husband.’

Molly gave her elder sister an indignant look. As usual, June’s thoughts were foremost with herself.

‘Of course, that’s not to say that now that you are engaged you can’t let him have a few little liberties, like – especially if he does have to go off to war. A girl doesn’t want to send her sweetheart off to fight without giving him a bit of a taste of what he’s fighting for, does she?’ June giggled. ‘Wait till we tell them at the factory on Monday that you’re engaged.’

The two sisters both worked as machinists at a small garment factory within walking distance of their home. Mr Harding, the factory owner, employed nearly twenty girls. June had got a job there when she left school, having seen it advertised in the Liverpool paper, and she had approached Mr Harding on Molly’s behalf a couple of months before Molly was due to leave school, to ask that her sister be considered for any likely vacancy. It was piece work and unless you were very quick and didn’t make any mistakes the pay wasn’t good, but it was no worse than the girls would have earned anywhere else, and as June often said, at least the small factory was clean, and warm in winter as Mr Harding was well aware that cold fingers didn’t work as nimbly and made mistakes – expensive mistakes for him if his customers rejected the work as not good enough. The other girls were a jolly bunch and, whilst they were all older than Molly, their company meant that there was always someone for her to have a laugh with.

The factory’s main business came from a distributor who provided them with both pattern and fabric and who supplied clothes to the big Lewis’s store in the centre of the city. Sometimes the girls were allowed to buy leftover pieces of cloth to make things for themselves. Two or three times a year, a very important dark-suited gentleman from Lewis’s came up to the long sewing machine-filled room where the girls worked, to inspect their sewing. Molly was happy working there, even if June sometimes grumbled and complained.

Molly started to brush her hair again. Both girls had thick, naturally curly hair. June’s was a mid-brown, but Molly’s was much darker and richer, with a warm chestnut hue.

Pensively, Molly stared into the mirror, her cornflower-blue eyes clouding. Her mouth trembled and she blinked away tears.

‘Now what’s up?’ June demanded, pinching her younger sister’s arm almost crossly.

‘Nothing,’ Molly fibbed.

‘I should jolly well think there isn’t. You don’t know how lucky you are, our Molly. There’s a lot of girls in Liverpool would give their right arms to be in your shoes and engaged to a handsome lad like Johnny. And besides …’

Molly could see that June was looking very determined, and her heart sank. She had been hoping that June would understand her feelings but now she could tell that she wasn’t going to get very much sympathy from her.