Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Forsaken Inn

So I went out, having learned nothing, save the fact that mademoiselle had a lover, and that her lips could smile.

They did not smile again, however. Next day she looked whiter than ever, and languid as a broken blossom.

"She is ill," declared madame. "The stairs she has to climb are too much for her."

"Ah, ha!" thought I to myself. "That is the first move," and waited for the next development.

It has not come as soon as I expected. Two days have passed, and though Mademoiselle Letellier grows paler and thinner, nothing more has been said about the stairs. But the time has not passed without its incident, and a serious enough one, too, if these women are, as I fear, in the secret of the hidden chamber.

It is this: In the garden is a white stone. It is plain-finished but unlettered. It marks the resting-place of Honora Urquhart. For reasons which we all thought good, we have taken no uninterested person into the secret of this grave, any more than we have into that of the hidden chamber.

Consequently no one in the house but myself could answer Madame Letellier, when, stopping in her short walk up and down the garden path, she asked what the white stone meant and what it marked. I would not answer her. I had seen from the window where I stood the quick surprise with which she had come to a standstill at the sight of this stone, and I had caught the tremble in her usually steady voice as she made the inquiry I have mentioned above. I therefore hastened down and joined her before she had left the spot.

"You are wondering what this stone means," I observed, with an indifferent tone calculated to set her at her ease. Then suddenly, and with a changed voice and a secret look into her face, I added: "It is a headstone; a dead body lies here."

She quivered, and her lids fell. For all her self-possession—and she is the most self-possessed person I ever saw in my life—she showed a change that gave me new thoughts and made me summon up all the strength I am mistress of, in order to preserve the composure which her agitation had so deeply shaken.

"You shock me," were her first words, uttered very slowly, and with a transparent show of indifference. "It is not usual to find a garden used for a burial place. May I ask whose body lies here? That of some faithful black or of a favorite horse?"

"It is not that of a horse," I returned, calmly. And greatly pleased to find that I had placed her in a position where she would be obliged to press the question if she would learn anything more, I walked slowly on, convinced that she would follow me.

She did, giving me short side glances, which I bore with an equanimity that much belied the tempest of doubt, repugnance and horror that were struggling blindly in my breast. But she did not renew the subject of the grave. Instead of that, she opened one of her most fascinating conversations, endeavoring by her wiles and graces to get at my confidence and insure my good will.

And I was hypocrite enough to deceive her into thinking she had done so. Though I showed her no great warmth, I carefully restrained myself from betraying my real feelings, allowing her to talk on, and giving her now and then an encouraging word or an inviting smile.

For I felt that she was a serpent and must be met as such. If she were the woman I thought her, I should gain nothing and lose all by betraying my distrust, while if she felt me to be her dupe I might yet light upon the secret of her interest in the oak parlor.

Her daughter was waiting for us in the doorway when we reached the house. At the sight of her pure face, with its tender gray eyes and faultless features, a strong revulsion seized me, and I found it difficult not to raise my arms in protest between her beauty and winning womanliness and the subtile and treacherous-hearted being who glided so smoothly toward her. But the movement, had I made it, would have been in vain. At the sight of each other's faces a lovely smile arose on the daughter's lips, while on the mother's flashed a look of love which would be unmistakable even on the countenance of a tiger, and which was at this moment so vivid and so real that I never doubted again, if I had ever doubted before, that mademoiselle was her own child—flesh of her flesh, and bone of her bone.

"Ah, mamma," cried one soft voice, "I have been so lonesome!"

"Darling," returned the other, in tones as true and caressing, "I will not leave you again, even for a walk, till you are quite well." And taking her by the waist, she led her down the hall toward the stairs, looking back at me as she did so, and saying: "I cannot take her to Albany until she is better. You must think what we can do to make her strong again, Mrs. Truax." And she sighed as she looked up the short flight of stairs her daughter had to climb.

October 15, 1791.That stone in the garden seems to possess a magnetic attraction for madame. She is over it or near it half the time. If I go out in the early morning to gather grapes for dinner, there she is before me, pacing up and down the paths converging to that spot, and gazing with eager eyes at that simple stone, as if by the force of her will she would extract its secret and make it tell her what she evidently burns to know. If I want flowers for the parlor mantel, and hurry into the garden during the heat of the day, there is madame with a huge hat on her head, plucking asters or pulling down apples from the low-hanging branches of the trees. It is the same at nightfall. Suspicious, always suspicious now, I frequently stop, in passing through the upper western hall, to take a peep from the one window that overlooks this part of the garden. I invariably see her there; and remembering that her daughter is ill, remembering that in my hearing she promised that daughter that she would not leave her again, I feel impelled at times to remind her of the fact, and see what reply will follow. But I know. She will say that she is not well herself; that the breeze from the river does her good; that she loves nature, and sleeps better after a ramble under the stars. I cannot disconcert her—not for long—and I cannot compete with her in volubility and conversational address, so I will continue to play a discreet part and wait.

October 17, 1791.Madame has become bolder, or her curiosity more impatient. Hitherto she has been content with haunting the garden, and walking over and about that one place in it which possesses peculiar interest for her and me. But this evening, when she thought no one was looking, when after a hurried survey of the house and grounds she failed to detect my sharp eyes behind the curtain of the upper window, she threw aside discretion, knelt down on the sod of that grave, and pushed aside the grass that grows about the stone, doubtless to see if there was any marks or inscription upon it. There are none, but I determined she should not be sure of this, so before she could satisfy herself, I threw up the window behind which I stood, making so much noise that it alarmed her, and she hastily rose.

I met her hasty look with a smile which it was too dark for her to see, and a cheerful good evening which I presume fell with anything but a cheerful sound upon her ears.

"It is a lovely evening," I cried. "Have you been admiring the sunset?"

"Ah, so much!" was her quick reply, and she began to saunter in slowly. But I knew she left her thoughts out there with that mysterious grave.

12 m.Another midnight adventure! Late as it is, I must put it down, for I cannot sleep, and to-morrow will bring its own story.

I had gone to bed, but not to sleep. The anxieties under which I now labor, the sense of mystery which pervades the whole house, and the secret but ever-present apprehension of some impending catastrophe, which has followed me ever since these women came into the house, lay heavily on my mind, and prevented all rest. The change of room may also have added to my disturbance. I am wedded to old things, old ways, and habitual surroundings. I was not at home in this small and stuffy apartment, with its one narrow window and wretched accommodations. Nor could I forget near what it lay, nor rid myself of the horror which its walls gave me whenever I realized, as I invariably did at night, that only a slight partition separated me from the secret chamber, with its ghastly memories and ever to be remembered horrors.

I was lying, then, awake, when some impulse—was it a magnetic one?—caused me to rise and look out of the window. I did not see anything unusual—not at first—and I drew back. But the impulse returned, and I looked again, and this time perceived among the shadows of the trees something stirring in the garden, though what I could not tell, for the night was unusually dark, and my window very poorly situated for seeing.

But that there was something there was enough, and after another vain attempt to satisfy myself as to its character, I dressed and went out into the hall, determined to ascertain if any outlet to the house was open.

I did not take a light, for I know the corridors as I do my own hand. But I almost wished I had as I sped from door to door and window to window; for the events which had blotted my house with mystery were beginning to work upon my mind, and I felt afraid, not of my shadow, for I could not see it, but of my step, and the great gulfs of darkness that were continually opening before my eyes.

However, I did not draw back, and I did not delay. I tried the front door, and found it locked; then the south door, and finally the one in the kitchen. This last was ajar. I knew then what had happened. Madame has had more than one talk with Chloe lately, and the good negress has not been proof against her wiles, and has taught her the secret of the kitchen lock. I shall talk to Chloe to-morrow. But, meantime, I must follow madame.

But should I? I know what she is doing in the garden. She is wandering round and round that grave. If I saw her I could not be any surer of the fact, and I would but reveal my own suspicions to her by showing myself as a spy. No; I will remain here in the shadows of the kitchen, and wait for her to return. The watch may be weird, but no weirder than that of a previous night. Besides, it will not be a long one; the air is too chilly outside for her to risk a lengthy stay in it. I shall soon perceive her dark figure glide in through the doorway.

And I did. Almost before I had withdrawn into my corner I heard the faint fall of feet on the stone without, then the subdued but unmistakable sound of the opening door, and lastly the locking of it and the hasty tread of footsteps as she glided across the brick flagging and disappeared into the hall beyond.

"She has laid the ghost of her unrest for to-night," thought I. "To-morrow it will rise again." And I felt my first movement of pity for her.

Alas! does that unrest spring from premeditated or already accomplished guilt? Whichever it may be—and I am ready to believe in either or both—she is a burdened creature, and the weight of her fears or her intentions lies heavily upon her. But she hides the fact with consummate address, and when under the eyes of people smiles so brightly and conducts herself with such a charming grace that half the guests that come and go consider her as lovely and more captivating than her daughter. What would they think if they could see her as I do rising in the night to roam about a grave, the unmarked head-stone of which baffles her scrutiny?

October 18, 1791.This morning I rose at daybreak, and going into the garden, surveyed the spot which I had imagined traversed by Madame Letellier the night before. I found it slightly trampled, but what interested me a great deal more than this was the fact that, on a certain portion of the surface of the stone I have so often mentioned, there were to be seen small particles of a white substance, which I soon discovered to be wax.

Thus the mystery of her midnight visit is solved. She has been taking an impression of what, in her one short glimpse of yesterday evening, she had thought to be an inscription. What a wonderful woman she is! What skill she shows; what secrecy and what purpose. If she cannot compass her end in one way, she will in another; and I begin to have, notwithstanding my repugnance and fear, a wholesome respect for her ability and the relentless determination which she shows in every action she performs.

When she finds that her wax shows her nothing but the natural excrescences and roughnesses of an unhewn stone, will she persist in her visits to the garden? I think not.

October 19, 1791.My last surmise was a true one. Madame has not spent a half hour all told in the garden since that night. She has turned her attention again to the oak parlor, and soon we shall see her make some decided move in regard to it.

CHAPTER XXI.

IN THE OAK PARLOR

October 20, 1791.THE long expected move has been made. This morning madame asked me if I had not some room on the ground floor which I could give to her daughter and her in exchange for the one they now occupy. Her daughter had been accustomed to living on one floor, and felt the stairs keenly.

I answered at first—"No." Then I appeared to bethink me, and told her, with seeming reluctance, that there was one room below which I sometimes opened to guests, but that just now it was in such a state of dilapidation I had shut it up till I could find the opportunity of repairing it.

"Oh!" she replied, subduing her eagerness to the proper point, "you need not wait for that. We are not particular persons. Only let me see the roses come back to my daughter's cheeks, and I can bear any amount of discomfort. Where is this room?"

I pretended not to hear her.

"It would take two days to get it into any sort of condition fit for sleeping in," I murmured reflectively. "The floor is so loose in places that you cannot walk across it without danger of falling through. Then there is the chimney—"

She was standing near me and I heard her draw her breath quickly, but she gave no other sign of emotion, not even in the sound of her voice as she interrupted me with the words:

"Oh! if you have got to make the room all over, we might as well not consider the subject. But I am sure it is not necessary. Do let me see it, and I can soon tell you whether we can be comfortable there or not."

I had sworn to myself never to enter that room again, but such oaths are easily broken. Leaving her for a moment, I procured my key, and taking her with me down the west hall, I unlocked the fatal door and bade her enter.

She hesitated for an instant, but only for an instant. Then she walked coolly in, and stood waiting while I crossed the floor to the window and threw it open. Her first glance flashed to the mantel and its adjacent wainscoting; then, finding everything satisfactory in that direction, it flew over the desolate walls and stiff, high-backed chairs, till it rested on the bare four-poster, denuded of its curtains and coverlets.

"A gloomy place!" she declared; "but you can easily make it look inviting with fresh curtains and a cheerful fire. I am sure that, dismal as it is, it will be more welcome to my daughter than the sunny room up stairs. Besides, the window looks out on the river, and that is always interesting. You will let us come here, will you not? I am sure, if we are willing, you ought to be."

I gasped inwardly, and agreed with her. Yet I made a few more objections. But as I intended that she should sleep in this room, I finally cleared my brow, and announced that the room should be ready for her occupancy on Friday; and with this she had to be content.

October 21.Bless God that I am mistress in my own house! I can order, I can have performed whatever I choose, without fuss, without noise, and without gossip. This is very fortunate just now, for while I am openly having the floor mended in the oak parlor, I am secretly having another piece of work done, which, if once known, would arouse suspicions and awaken conjectures that would destroy all my plans concerning the mysterious guests who insist upon inhabiting the accursed oak parlor.

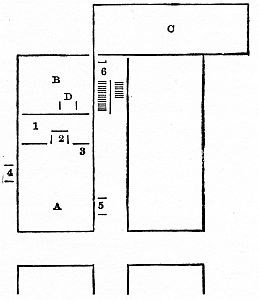

What this work is can be best understood by a glance at the accompanying diagram, which is a copy of the one drawn up by the Englishman for Mr. Tamworth.

A—Oak parlor. B—Bedroom. C—Kitchen, etc. D—Passage I have had made.

1—Secret chamber. 2—Fire-place. 3—Secret spring. 4—Garden window. 5—Door to oak parlor. 6—Clock on stairs to second story. Entrance to room B under stairway.

Here you see that the secret chamber lies between the rooms A and B. A is the parlor and B is the small room in which I had put up my bed after the nocturnal adventure of October 10. It has always been used as a store room until now, and as no one handles the keys of this house but myself, the fact of my using it for any other purpose is known only to Margery and a certain quiet and reticent workman from Cruger's shop, to whom I have intrusted the task of opening a passage at D through the wall. For I must have proper means of communication with this room before I can allow Madame Letellier and her daughter to take up their abode in it. Though the former's plans are a mystery to me; though I feel that she loves her daughter, and, therefore, cannot meditate evil against her, still my doubts of her are so great that I must know her intentions, if possible, and to do this I contemplate keeping a watch over that den of wicked memories which will be at once both unsuspected and vigilant.

The flooring of the parlor is nearly completed, and to-night will see the door of communication between my room and the secret chamber hung and ready for use.

October 22.A month ago, if any one had told me that I would not only walk of my own free will into the secret chamber, but take up my abode in it, eat in it and sleep in it, I would have said that person was mad. And yet this is just what I have done.

The result of my first vigil was unexpected. I had looked for—well, I hardly know what I did look for. My anticipations were vague, but they did not lead me in the right direction. But let me tell the story. After I had installed my guests in their new apartment, I informed them that I would have to say good-by for a season, as I had an affection of the eyes—which was true enough—which at times compelled me to shut myself up in a dark room and forego all company. That I felt one of these spells coming on—which was not true—and that by a speedy resort to darkness and quiet, I hoped to prevent the attack from reaching its usual point of distress. Mademoiselle Letellier looked disappointed, but madame ill disguised her relief and satisfaction. Convinced now beyond all doubt that she had some plan in mind which made her dread my watchfulness, I made such final arrangements as were necessary, and betook myself at once to my new room. Once there, I moved immediately into the dark chamber, and walking with the utmost circumspection, crossed to the wall adjoining the oak parlor, and laying my ear against the opening into that room, I listened.

At first I heard nothing, probably because its inmates were still. Then I caught an exclamation of weariness, and soon some words of desultory conversation. Relieved beyond expression, not only because I could hear, but because they talked in English, I withdrew again into my own room. The most difficult problem in the world was solved. I had found the means by which I could insinuate myself, unseen and unsuspected, into the secret confidences of two women, at moments when they felt themselves alone and at the mercy of no judgment but that of God. Should I learn enough to pay me for the humiliation of my position? I did not weary myself by questioning. I knew my motive was pure, and fixed my mind upon that.

Several times before the day was over did I return to the secret chamber and bend my ear to the wall. But in no instance did I linger long, for if the two ladies spoke at all it was on trivial subjects, and in such tones as indicated that neither their passions nor any particular interests were engaged. For such talk I had no ear.

"It will not be always so," I thought to myself. "When night comes and the heart opens, they will speak of what lies upon their minds."

And so it happened. As the inn grew quiet and the lights began to disappear from the windows, I crept again to my station against the partition, and in a darkness and atmosphere that at any other time in my life would have completely unnerved me, hearkened to the conversation within.

"Oh, mamma," were the first words I heard, uttered in English, as all their talk was when they were moved or excited, "if you would only explain! If you would only tell me why you do not wish me to receive letters from him! But this silence—this love and this silence are killing me. I cannot bear it. I feel like a lost child who hears its mother's voice in the darkness, but does not know how to follow that voice to the refuge it bespeaks."

"Time was when daughters found it sufficient to know that their parents disapproved of an act, without inquiring into their reasons for it. Your father has told you that the marquis is not eligible as a husband for you, and he expects this to content you. Have I the right to say more than he?"

"Not the right, perhaps, mamma. I do not appeal to your sense of right, but to your love. I am very unhappy. My whole life's peace is trembling in the balance. You ought to see it—you do see it—yet you let me suffer without giving me one reason why I should do so."

The mother's voice was still.

"You see!" the daughter went on again, after what seemed like a moment of helpless waiting. "Though my arms are about you, and my cheek pressed close to yours, you will not speak. Do you wonder that I am heart-broken—that I feel like turning my face to the wall and never looking up again?"

"I wonder at nothing."

Was that madame's voice? What boundless misery! what unfathomable passion! what hopeless despair!

"If he were unworthy!" her daughter here exclaimed.

"It you could point to anything he lacks. But he has wealth, a noble name, a face so handsome that I have seen both you and papa look at him in admiration; and as for his mind and attainments, are they not superior to those of all the young men who have ever visited us? Mamma, mamma, you are so good that you require perfection in a son-in-law. But is he not as near it as a man may be? Tell me, darling, for in my dreams he always seems so."

I heard the answer, though it came slowly and with apparent effort.

"The marquis is an admirable young man, but we have another suitor in mind whose cause we more favor. We wish you to marry Armand Thierry."

"A shop-keeper and a revolutionist! Oh, mamma!"

"That is why we brought you away. That is why you are here—that you might have opportunity to bethink yourself, and learn that the parents' views in these matters are the truest ones, and that where we make choice, there you must plight your troth. I assure you that our reasons are good ones, if we do not give them. It is not from tyranny—"

Here the set, strained voice stopped, and a sudden movement in the room beyond showed that the mother had risen. In fact, I presently heard her steps pacing up and down the floor.

"I know it is not tyranny," the daughter finished, in the soft tones that were so great a contrast to her mother's. "Tyranny I could have understood; but it is mystery, and that is not so easily comprehended. Why should you and papa be mysterious? What is there in our simple life to create secrecy between persons who love each other so dearly? I see nothing, know nothing; and yet—"

"Honora!"

The word struck me like a blow. "Honora!" Great heaven! was that the name of this young girl?

"You are giving too free range to your imagination. You—"

I did not hear the rest. I was thinking of the name I had just heard, and wondering if my suspicions were at fault. They would never have called their child Honora. Who were these women, then? Friends of the Dudleighs? Avengers of the dead? I glued my ear still closer to the wall.

"We have cherished you." The mother was still speaking. "We have given you all you craved, and more than you asked. From the moment you were born we have both lavished all the tenderness of our hearts upon you. And all we ask in return is trust." The hard voice, hard because of emotion, I truly believe, quavered a little over that word, but spoke it and went on. "What we do for you now, as always, is for your best good. Will you not believe it, Honora?"