Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

What I know of farming:

The Seventh Census (1850) returned the Hay-crop of the preceding year at 13,838,642 tuns, which the Eighth Census increased to 19,129,128 tuns as the product of 1859. Confident that most farmers underestimate their Hay-crops, and that hundreds of thousands who do not consider themselves farmers, but who own or rent little homesteads of two to ten acres each, keeping thereon a cow or two and often a horse, fail to make returns of the two to five tuns of Hay they annually produce, considering them too trivial, I estimate the actual Hay-crop of all our States and Territories for the current year at 40,000,000 tuns, or about a tun to each inhabitant, although I do not expect the new Census to place it much, if any, above 25,000,000 tuns. The estimated average value of this crop is $10 (gold) per tun, making its aggregate value, at my estimate of its amount, $400,000,000 – and the quantity is constantly and rapidly increasing.

That quantity should be larger from the area devoted to meadows, and the quality a great deal better. I estimate that 30,000,000 acres are annually mowed to obtain these 40,000,000 tuns of Hay, giving an average yield of 1-1/3 tuns per acre, while the average should certainly not fall below two tuns per acre. My upland has a gravelly, rocky soil, not natural to grass, and had been pastured to death for at least a century before I bought it; yet it has yielded me an average of not less than 2-1/2 tuns to the acre for the last sixteen years, and will not yield less while I am allowed to farm it. My lowland (bog when I bought it) is bound henceforth to yield more; but, while imperfectly or not at all drained, it was of course a poor reliance – yielding bounteously in spots, in others, little or nothing.

In nothing else is shiftless, slovenly farming so apt to betray itself as in the culture of Grass and the management of grass lands. Pastures overgrown with bushes and chequered by quaking, miry bogs; meadows foul with every weed, from white daisy up to the rankest brakes, with hill-sides that may once have been productive, but from which crop after crop has been taken and nothing returned to them, until their yield has shrunk to half or three-fourths of a tun of poor hay, these are the average indications of a farm nearly run out by the poorest sort of farming. Such farms were common in the New England of my boyhood; I trust they are less so to-day; yet I seldom travel ten miles in any region north or east of the Delaware without seeing one or more of them.

Fifty years ago, I judge that the greater part of the hay made in New-England was cut from sour, boggy land, that was devoted to grass simply because nothing else could be done with it. I have helped to carry the crop off on poles from considerable tracts on which oxen could not venture without miring. It were superfluous to add that no well-bred animal would eat such stuff, unless the choice were between it and absolute starvation. In many cases, a very little work done in opening the rudest surface-drains would have transformed these bogs into decent meadows, and the product, by the help of plowing or seeding, into unexceptionable hay.

There are not many farmers, apart from our wise and skillful dairymen, who use half enough grass-seed; men otherwise thrifty often fail in this respect. If half our ordinary farmers would thoroughly seed down a full third of the area they usually cultivate, and devote to the residue the time and efforts they now give to the whole, they would grow more grain and vegetables, while the additional grass would be so much clear again.

We sow almost exclusively Timothy and Clover, when there are at least 20 different grasses required by our great diversity of soils, and of these three or four might often be sown together with profit; especially in seeding down fields intended for pasture, we might advantageously use a greater variety and abundance of seed. I believe that there are grasses not yet adopted and hardly recognized by the great body of our farmers – the buffalo-grass of the prairies for one – that will yet be grown and prized over a great part of our country.

As for Hay-Making, my conviction is strong that our grass is cut in the average from two to three weeks too late, and that not only is our hay greatly damaged thereby, but our meadows needlessly impoverished and exhausted. The formation and perfection of seed always draw heavily upon the soil. A crop of grass cut when the earliest blossoms begin to drop – which, in my judgment, is the only right time – will not impoverish the soil half so much as will the same crop cut three weeks later; while the roots of the earlier cut grass will retain their vitality at least thrice as long as though half the seed had ripened before the crop was harvested. Grass that was fully ripe when cut has lost at least half its nutriment, which no chemistry can ever restore. Hay alone is dry fodder for a long Winter, especially for young stock; but hay cut after it was dead ripe, is proper nutriment for no animal whatever – not even for old horses, who are popularly supposed to like and thrive upon it.

The fact that our farmers are too generally short-handed throughout the season of the Summer harvest, while it seems to explain the error I combat, renders it none the less disastrous and deplorable. I estimate the depreciation in the value of our hay-crop, by reason of late cutting, as not less than one-fifth; and, when we consider that a full half of our farmers turn out their cattle to ravage and poach up their fields in quest of fodder a full month earlier than they should, because their hay is nearly or quite exhausted, the consequences of this error are seen to diffuse themselves over the whole economy of the farm.

From the hour in which grass falls under the Mower, it ought to be kept in motion until laid at rest in the stack or the barn; keep stirring it with the tedder until it is ready to be raked into light winrows, and turn these over and over until they will answer to go upon the cart. In any bright, hot day, the grass mowed in the morning should be stacked before the dew falls at night; while, if any is mowed after noon, it should be cocked and capped by sunset, even though it be necessary to open it out the next fair morning.

I have a dream of hay-making, especially with regard to clover, without allowing it to be scalded by fierce sunshine. In my dream, the grass is raked and loaded nearly as fast as cut, drawn to the barn-yard, and there pitched upon an endless apron, on which it is carried slowly through a drying-house, heated to some 200° Fahrenheit by steam or by charcoal in a furnace below, somewhat after the manner of a hop-kiln. While passing slowly through this heated atmosphere, the grass is continually forked up and shaken so as to expose every lock of it to the drying heat, until it passes off thereby deprived of its moisture and is precipitated into a mow or upon a stack-bottom at the opposite side; load after load being pitched upon the apron continuously, and the drying process going steadily forward by night as well as by day, and without regard to the weather outside. I do not assert that this vision will ever be realized; but I have known dreams as wild as this transformed by time and thought into beneficent realities.

I ask no one to share my dreams or sympathise with their drift and purpose. I only insist that Hay-making, as it is managed all around me, is ruder in its processes and more uncertain in its results than it should or need be. We cut our grass rapidly and well; we gather and house it with tolerable efficiency; but we cure much of it imperfectly and wastefully. The fact that most of it is over-ripe when cut aggravates the pernicious effects of its subsequent exposure to dew and rain; and the net result is damaged fodder which is at once unpalatable and innutritious.

XXVII.

PEACHES – PEARS – CHERRIES – GRAPES

Our harsh, capricious climate north of the latitudes of Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and St. Louis – so much severer than that of corresponding latitudes in Europe – is unfavorable, or at least very trying, to all the more delicate and luscious Fruits, berries excepted. Except on our Pacific coast, of which the Winter temperature is at least ten degrees milder than that of the Atlantic, the finer Peaches and Grapes are grown with difficulty north of the fortieth degree of latitude, save in a few specially favored localities, whereof the southern shore of Lake Erie is most noted, though part of that of Lake Ontario and of the west coast of Lake Michigan are likewise well adapted to the Peach.

It is not the mere fact that the mercury in Fahrenheit's thermometer sometimes ranges below zero, and the earth is deeply frozen, but the suddenness wherewith such rigor succeeds and is succeeded by a temperature above the freezing point, that proves so inhospitable to the most valued Tree-Fruits. And, as the dense forests which formerly clothed the Alleghenies and the Atlantic slope, are year by year swept away, the severity of our "cold snaps," and the celerity with which they appear and disappear, are constantly aggravated. A change of 60°, or from 50° above to 10° below zero, between morning and the following midnight, soon followed by an equally rapid return to an average November temperature, often proves fatal even to hardy forest-trees. I have had the Red Cedar in my woods killed by scores during an open, capricious Winter; and my observation indicates the warmest spots in a forest as those where trees are most likely to be thus destroyed. After an Arctic night, in which they are frozen solid, a bright sun sends its rays into the warmest nooks, whence the wind is excluded, and wholly or partially thaws out the smaller trees; which are suddenly frozen solid again so soon as the sunshine is withdrawn; and this partly explains to my mind the fact that peach-buds are often killed in lower and level portions of an orchard, while they retain their vitality on the hill-side and at its crest, not 80 rods distant from those destroyed. The fact that the colder air descends into and remains in the valleys of a rolling district contributes also to the correct explanation of a phenomenon which has puzzled some observers.

Unless in a favored locality, it seems to the unadvisable for a farmer who expects to thrive mainly by the production of Grain and Cattle, to attempt the growing of the finer Fruits, except for the use of his own family. In a majority of cases, a multiplicity of cares and labors precludes his giving to his Peaches and Grapes, his Plums and Quinces, the seasonable and persistent attention which they absolutely require. Quite commonly, a farmer visits a grand nursery, sees with admiration its trees and vines loaded with the most luscious Fruits, and rashly infers that he has only to buy a good stock of like Trees and Vines to insure himself an abundance of delicious fruit. So he buys and sets; but with no such preparation of the soil, and no such care to keep it mellow and free from weeds, or to baffle and destroy predatory insects, as the nurseryman employs. Hence the utter disappointment of his hopes; borers, slugs, caterpillars, and every known or unknown species of insect enemies, prey upon his neglected favorites. At intervals, some domestic animal or animals get among them, and break down a dozen in an hour. So, the far greater number come to grief, without having had one fair chance to show what they could do, and the farmer jumps to the conclusion that the nurseryman was a swindler, and the trees he sells scarcely related to those whose abundant and excellent fruits tempted him to buy. I counsel every farmer to consider thoughtfully the treatment absolutely required for the production of the finer Fruits before he allows a nurseryman to make a bill against him, and not expect to grow Duchesse Pears as easily as Blackberries, or Ionas and Catawbas as readily as he does Fox-grapes on the willows which overhang his brook; for if he does he will surely be disappointed.

Some of our hardier and coarser Grapes – the Concord preëminent among them – are grown with considerable facility over a wide extent of our country; and many farmers, having planted them in congenial soil, and tended them well throughout their infancy, are rewarded by a bounteous product for two or three years. Believing their success assured, they imagine that their vines may henceforth be neglected, and in the course of two or three more years they are often utterly ruined. I know that there are wild grapes of some value, in the absence of better, which thrive and bear without attention; but I do not believe that any grape which will sell in a market where good fruit was ever seen, can be grown north of Philadelphia but by constant care and labor, or at a cost of less than five cents per pound, under the most judicious and skillful treatment. In California, and I presume in most of our States south of the Potomac and Ohio, choice grapes may be grown more abundantly and more cheaply. Yet I think the localities are few and far between in which a tun of good grapes can be grown as cheaply as a tun of wheat, under the most judicious cultivation in either case.

I do not mean to discourage grape-growing; on the contrary, I would have every farmer, even so far north as Vermont and Wisconsin, experiment cautiously with a dozen of the most promising varieties, including always the more hardy, in the hope of finding some one or more adapted to his soil, and capable of enduring his climate. Even in France, the land of the vine, one farm will produce a grape which the very next will not: no man can satisfactorily say why. The farmer, who has tried half a dozen grapes and failed with all, should not be deterred from further experiments, for the very next may prove a success. I would only say, Be moderate in your expectations and careful in your experiments; and never risk even $100 on a vineyard, till you have ascertained, at a cost of $5 or under, whether the species you are testing will thrive and bear on your soil.

In my own case, my upland mainly sloping to the west, with a hill rising directly south of it, I have had no luck with Grapes, and I have wasted little time or means upon them. I have done enough to show that they can be grown, even in such a locality, but not to profit or satisfaction.

I would advise the farmer who proposes to grow Pear, Peaches, and Quinces, for home use only or mainly, to select a piece of dry, gravelly or sandy loam, underdrain it thoroughly, plow or trench it very deeply, and fertilize it generously, in good part with ashes and with leaf-mold from his woods. Locate the pig-pen on one side of it, fence it strongly, and let the pigs have the run of it for a good portion of each year. In this plat or yard, plant half a dozen Cherry and as many Pear trees of choice varieties, the Bartlett foremost among them; keep clear of all dwarfs, and let your choicest trees have a chance to run under the pig-pen if they will. Plant here also, if your climate does not forbid, a dozen well-chosen Peach-trees, and two each year thereafter to replace those that will soon be dying out; and give half a dozen Quinces moist and rich locations by the side of your fences; surrounding each tree with stakes or pickets that will preclude too great familiarity on the part of the swine, and will not prevent a sharp scrutiny for borers in their season. Do not forget that a fruit-tree is like a cow tied to an immovable stake, from which you cannot continue to draw a pail of milk per day unless you carry her a liberal supply of food; and every Fall cart in half a dozen loads of muck from some convenient swamp or pond for your pigs to turn over: Should they leave any weeds, cut them with a scythe as often as they seem to need it; never allowing one to ripen seed. There may be easier and surer ways to obtain choice fruits; but this one commends itself to my judgment as not surpassed by any other. I think few have grown fruits to profit but those who make this a specialty; and I feel that disappointment in fruit-culture is by no means near the end. You can grow Plums, or Grapes, or Peaches, outside of the climate most congenial to them, but this is a work wherein success is likely to cost more than its worth. Try it first on a small scale, if you will try it; and be sure you do it thoroughly.

XXVIII.

GRAIN-GROWING – EAST AND WEST

I disclaim all pretensions to ability to teach Western farmers how to grow Indian Corn abundantly and profitably, while I cheerfully admit that they have taught me somewhat thoroughly worth knowing. In my boyhood, I hoed Corn diligently for weeks at a time, drawing the earth from between the rows up about the stalks to a depth of three or four inches; thus forming hills which the West has since taught me to be of no use, but rather a detriment, embarrassing the efforts of the growing, hungry plants to throw out their roots extensively in every direction, and subjecting them to needless injury from drouth. I am thoroughly convinced that Corn, properly planted, will, like Wheat and all other grains, root itself just deep enough in the ground, and that to keep down all weeds and leave the surface of the corn-field open, mellow and perfectly flat, is the best as well as the cheapest way to cultivate Corn. And I do not believe that so much human food, with so little labor, is produced elsewhere on earth as in the spacious fields of Wheat and Corn in our grand Mississippi valley.

And yet I have seen in that valley many ample stretches covered with Corn, whereof the tillage seemed susceptible of improvement. Riding between these great corn-fields in October, after everything standing thereon had been killed by frost, it seemed to my observation that, while the corn-crop was fair, the weed-crop was far more luxuriant; so that, if everything had been cut clean from the ground, and the corn and the weeds placed in opposite scales, the latter would have weighed down the former. I cannot doubt that the cultivation, or lack of cultivation, which produces or permits such results, is not merely slovenly, but unthrifty.

The West is for the present, as for a generation she has been, the granary of the East. In my judgment, she will not long be content to remain so. Fifty years ago, the Genesee valley supplied most of the wheat and flour imported into New-England; ten years later, Northern Ohio was our principal resource; ten years later still, Michigan, Indiana, northern Illinois, and eastern Wisconsin, had been added to our grain-growing territory. Another decade, and our flour manufacturers had crossed the Mississippi, laying Iowa and Minnesota under liberal contributions, while western New-York had ceased to grow even her own breadstuffs, and Ohio to produce one bushel more than she needed for home consumption. Can we doubt that this steady recession of our Egypt, our Hungary, is destined to continue? Twenty-three years ago, when I first rode out from the then rising village of Chicago to see the Illinois prairies, nearly every wagon I met was loaded with wheat, going into Chicago, to be sold for about fifty cents per bushel, and the proceeds loaded back in the form of lumber, groceries, and almost everything else, grain excepted, needed by the pioneers, then dotting, thinly and irregularly, that whole region with their cabins. Now, I presume the district I then traversed produces hardly more grain than it consumes; taking Illinois altogether, I doubt that she will grow her own breadstuffs after 1880; not that she will be unable to produce a large surplus, but that her farmers will have decided that they can use their lands otherwise to greater advantage. Iowa and Minnesota will continue to export grain for perhaps twenty years longer; but even their time will come for saying, "New-York and New-England (not to speak of Old England) are too far away to furnish profitable markets for such bulky products; the cost of transportation absorbs the larger part of the cargo. We must export instead Wool, Meat, Lard, Butter, Cheese, Hops, and various Manufactures, whereof the freight will range from 2 up to not more than 25 per cent. of the value." They thus save their soil from the tremendous exaction made by taking grain-crop after grain-crop persistently, which long ago exhausted most of New-England and eastern New-York of wheat-forming material, and has since wrought the same deplorable result in our rich Genesee valley; while eastern Pennsylvania, though settled nearly two centuries ago, having pursued a more rational and provident system of husbandry, grows excellent wheat-crops to this day.

I insist that the States this side of the Delaware; though they will draw much grain from the Canadas after the political change that cannot be far distant, will be compelled to grow a very considerable share of their own breadstuff; that the West will cease to supply them unless at prices which they will deem exorbitant; and that grain-growing eastward of a line drawn from Baltimore this north to the Lakes will have to be very considerably extended. Let us see, then, whether this might not be done with profit even now, and whether the East is not unwise in having so generally abandoned grain-growing.

I leave out of the account most of New-England, as well as of Eastern New-York, and the more rugged portions of New-Jersey and Pennsylvania, where the rocky, hilly, swampy face of the country seems to forbid any but that patchy cultivation, wherein machinery and mechanical power can scarcely be made available, and which seem, therefore, permanently fated to persevere in a system of agriculture and horticulture not essentially unlike that they now exhibit. In the valleys of the Penobscot, the Kennebec, the Hudson, and of our smaller rivers, there are considerable tracts absolutely free from these natural impediments, whereon a larger and more efficient husbandry is perfectly practicable, even now; but these intervales are generally the property of many owners; are cut up by roads and fences; and are held at high prices: so that I will simply pass them by, and take for illustration the "Pine Barrens" of Southern New-Jersey, merely observing that what I say of them is equally applicable, with slight modifications, to large portions of Long Island, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas.

The "Pine Barrens" of New-Jersey are a marine deposit of several hundred feet in depth, mainly sand, with which more or less clay is generally intermingled, while there are beds and even broader stretches of this material nearly or quite pure; the clay sometimes underlying the sand at a depth of 10 to 30 or 40 inches. Vast deposits of muck or leaf-mold, often of many acres in extent and from two to twenty feet in depth, are very common; so that hardly any portion of the dry or sandy land is two miles distant from one or more of them, while some is usually much nearer; and half the entire region is underlaid by at least one stratum of the famous marl (formed of the decomposed bones of gigantic marine monsters long ago extinct) which has already played so important and beneficent a part in the renovation and fertilization of large districts in Monmouth, Burlington, Salem, and other counties.

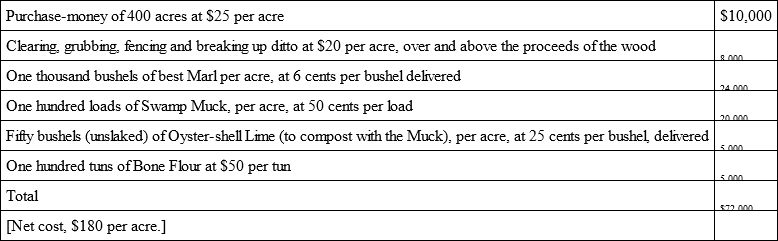

Let us suppose now that a farmer of ample means and generous capacity should purchase four hundred acres of these "barrens," with intent to produce therefrom, not sweet potatoes, melons, and the "truck" to which Southern Jersey is so largely devoted, but substantial Grain and Meat; and let us see whether the enterprise would probably pay.

Let us not stint the outlay, but, presuming the tract to be eligibly located on a railroad not too distant from some good marl-bed, estimate as follows:

I believe that this tract, divided by light fences into four fields of 100 acres each, and seeded in rotation to Corn, Wheat, Clover and other grasses, would produce fully 60 bushels of Corn and 30 of Wheat per acre, with not less than 3 tuns of good Hay; and that by cutting, steaming, and feeding the stalks and straw on the place, not pasturing, but keeping up the stock, and feeding them, as indicated in a former chapter of these essays, and selling their product in the form of Milk, Butter, Cheese and Meat, a greater profit would be realized than could be from a like investment in Iowa or Kansas. The soil is warm, readily frees itself, or is freed, from surplus water; is not addicted to weeds; may be plowed at least 200 days in a year; may be sowed or planted in the Spring, when Minnesota is yet solidly frozen; while the crop, early matured, is on hand to take advantage of any sudden advance in the European or our own seaboard markets. Labor, also, is cheaper and more rapidly procured in the neighborhood of this great focus of immigration than it is or can be in the West; and our capable farmers may take their pick of the workers thronging hither from Europe, at the moment of their landing on our shore. Of course, the owner of such an estate as I have roughly outlined, would be likely to keep a part of his purchase in timber, proving the quality thereof by cutting out the less desirable trees, trimming up the rest, and planting new ones among them; and he would be almost certain to devote some part of his farm annually to the growth of Roots, Vegetables, and Fruits. But I have aimed to show only that he would grow grain here at a profit, and I think I have succeeded. His 60 bushels of corn (shelled) per acre could be sold at his crib, one year with another, for 60 silver dollars; and he need seldom wait a month after husking it for customers who would gladly take his grain and pay the money for it. This would be just about double what the Iowa or Missouri farmer can expect to average for his Corn. The abundant fodder would also be worth in New-Jersey at least double its value in Iowa; and I judge that the farmer able to buy, prepare, fertilize, and cultivate 1,200 acres of the Jersey "barrens," could make more than thrice the profit to be realized by the owner of 400 acres. He would plow and seed as well as thrash, shell, cut stalks and straw, and prepare the food of his animals, wholly by steam-power, and would soon learn to cultivate a square mile at no greater expense than is now involved in the as perfect tillage of 200 acres.