Полная версия:

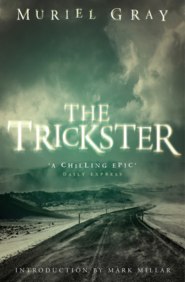

The Trickster

Calvin looked round the room from behind his mug of coffee. None of these people would ever be safe again if he didn’t act. That darkness would reach them all eventually, one way or another, once it had been released for good. Did he care? They certainly didn’t care about him. He saw himself through their eyes. A useless, drunken old grey-haired Indian, stinking of his own dried urine, a face lined by abuse and tragedy, wearing clothes that were like diseased and peeling skins instead of fabric. He was no saviour. But the Great Spirit, he knew, cared about them all; the girl behind the counter, the two surly young men in the corner in leather jackets and jeans, the working man on the next stool wearing the overalls of an elevator company, and Calvin Bitterhand. Loved them without question or prejudice. Prejudice was man’s invention.

Yes, even though the people in this room would never know that he thought of himself as their brother, it was his duty to act on their behalf. What else could he do? To ignore the Eagle and stay would mean life would go on as normal. He could peacefully spend the last few years of his life as scum on the streets, drinking himself nearer death and crying himself to sleep in doorways.

He must go to Silver and he must go now. But he was not pure enough to face what he knew was waiting for him. Nineteen years had passed since he’d left the reserve, and in all those years he’d never performed a sun dance, or fasted, not even prayed. He was tainted with self-abuse. Broken by booze. There was only one solution. Penance. He would walk. If he didn’t make the two hundred miles, then the Great Spirit had other plans for him. But he was going to try.

Calvin swallowed the last of his coffee and managed a weak smile at the girl moving some cakes around the display.

‘Want another, chief?’

He shook his head, climbed slowly and painfully off his stool and walked over to where she stood on the other side of the plastic-covered counter. She stopped toying with her cakes and straightened up to confront him. Calvin put his hands on the counter to steady himself, noticing her eyes flicking to the gaps where his fingers used to be. He held up his head and spoke to her softly.

‘I have a long journey now. No more money. You give me food?’

The waitress, Marie-Anne MacDonald, looked back at him and found herself hesitating. Normally she gave old bums the treatment they deserved. If they couldn’t pay they hit the street. You slipped one of them an old danish or a doughnut past its sell-by, and before you knew where you were you had a string of them hanging around the door expecting to be fed like dogs. It was her butt on the line and if Jack came in and saw her giving charity to any old scrounger it would certainly be her who’d get it in the neck. Okay, it wasn’t a great job, but it was a job. The shop shut at four so she had all afternoon to watch the soaps and then get ready to go out with Alan. Suited her fine, and she wasn’t going to lose it for a bum. Anyway, these people could work if they wanted to. They just didn’t want to. Look at her. She had to work didn’t she? Sure, she’d like to stand around all day drinking, but she came in here at seven-thirty every day to earn her crust, and she hated these Indian bums who thought life owed them a living. She let them in so she could take their money off them, the money they’d begged from some sucker, and then throw them out when they got comfortable. Marie-Anne sometimes wished she could teach the useless pigs that white people weren’t all one big welfare cheque.

At least that was the rule she lived by normally. This guy was different. When he looked at her just then, his black shiny eyes fixing her with a stare, there was no self-pity in them, no pleading or cajoling. More like defiance, as if he were ordering her to do something she knew she had to but had forgotten.

And she caught a strange scent from him, not of piss and liquor, but of a fresh wind and trees, the way washed sheets smell when they’ve been out on the line blowing in the spring breeze.

Made her think of when she was little and she and her father picnicked on the Bow River, way out of town. The mountains were like a jagged cut-out in the distance, and she would run through the pines, laughing as she fell in the long grass in the clearing between the trees. The smell was the same. Green, wet, fresh, delicious.

Marie-Anne, still looking into Calvin’s watery black eyes, put a hand absently into the refrigerated display case in the front of the counter, scooped eight cling-wrapped sandwiches into a bag and handed it to him.

Calvin took it, nodded to her and slowly, wearily, left the shop. She watched him go, transfixed as his hunched figure pushed the door open and shuffled past the window out of sight.

Eight sandwiches. She was in for it if she couldn’t account for how eight sandwiches walked right out of the cool shelf. Each one was worth a dollar sixty, in fact one had been a jumbo shrimp mayo, worth two dollars seventy-five. Without thinking she went into her pocket book under the coffee machine, took out thirteen dollars and put them in the till. Jack would never know. The elevator maintenance man called for another cup of coffee and Marie-Anne went to pour it, with a smile on her face that would last her until closing, although then, as now, she couldn’t tell you why.

13

It would be out of his hands in a few hours. The worst thing, as always, was that the media would go apeshit. Craig stared at Brenner’s slim report as if it told him he had a week to live. Instead, it told him loud and clear that Joe hadn’t died in a car accident, told him that Joe had been ripped apart and then tipped over the gorge as an afterthought.

There had been some grim excitement when the truck driver had been found, the one who kicked his own bucket on the highway. But when they hauled in the body there had been absolutely no sign of blood, a weapon or even a struggle. Zilch. The guy was clean as a whistle. In short, that poor bastard was certainly the last guy over the pass and probably the only witness they were going to get; but Craig was sure that no way did he murder Joe Reader.

He put his hands to his face and mashed the skin round his eyes. They would send someone from Edmonton now. The rules said you couldn’t lead an investigation if you were personally involved, and boy, was he involved. The guy who did that to Joe would know how involved if he ever found himself in a room with Craig.

He let his gaze wander from the document of doom on the desk to the window, where the falling snow was thicker than the fake stuff they used to chuck around on a John Denver Christmas special.

How to deal with the media. That was the next big one. Craig could just imagine how the ratings-hungry louses were going to cover this. What made better copy than a murder in a tourist town, where the biggest stink is usually some skis getting stolen, or some guy winning a busted face in a bar brawl? Suddenly, there’s a jackpot; two patrollers dying in a freak avalanche explosives accident, then a murder that would make Stephen King say yuk. All against a backdrop of folks having winter-wonderland fun in the snow. Christ, it would have the American networks circling Silver like crows round a carcass.

Bad thought. It made him see Joe again. Or what had been left of Joe. Craig sighed and replayed the tape in his head one more time. Joe’s pick-up was the second last vehicle to cross the pass that night. The truck came after. He was sure of that. Seen the tracks himself. The murderer couldn’t possibly have survived up there without a vehicle, so either he was in Joe’s car, or Legat’s.

Or both. Craig’s mouth opened slightly. Or both. In Joe’s truck as far as the gorge then hitched a ride in the Peterbilt. He got excited. Then he stopped getting excited. Joe’s truck had been pushed over the edge. Something really powerful had pushed it. A single killer and some old truck driver with a dodgy heart couldn’t possibly have done it by themselves. It would have taken either ten men or another vehicle, at least another pick-up. The snow that had fallen relentlessly for at least ten hours after the event made sure they would never know the answer to that one. A murderer couldn’t have chosen better conditions to cover his tracks. And anyway, why would someone like the Legat guy have taken part in such a foul deed? His records showed he was just a regular trucker: no record, nothing untoward, and strangely, for someone who just took the coward’s way out, nothing to suggest he would want to. The suicides Craig had dealt with in twenty years of policing were usually caused by drink, gambling debts, sexual problems or mental illness. Ernie Legat didn’t seem to suffer from any of them. Was he forced to do something despicable? Was that why he had committed suicide? Didn’t make sense. He would have just driven straight to the RCs if there had been any funny business and he’d survived. Craig pulled himself up. Legat wasn’t murdered, remember, just died of the cold. For the hundredth time he asked himself what the hell were they dealing with here.

The local TV and radio stations had covered the ski patrol deaths and Wolf River Valley Cable had run some crap about the dangers of avalanching. But this was the real thing. A bloody, messy, unexplained, motiveless cop-killing, bound to go network, and he shrank at the prospect. If their man was a psycho, headline news wouldn’t help. Where was the piece of shit now? That’s what he needed to know. The son of a bitch could be walking round town collecting for the blind as far as Craig knew, since right now Silver had more strangers than residents. That was, if he was still here. What if he was going the other way? To Stoke. He dismissed it. Instinct told Craig McGee the murderer was headed towards Silver.

He pushed the button on his phone. ‘Holly, I’m going out for an hour or two. Tell Sergeant Morris to hold the fort.’

It crackled back. ‘He’s out here already. There’s some messages. Do you need them now?’

Craig smiled. His wife used to say Holly was like something out of Twin Peaks. Even if he wanted to dispute it, his secretary gave him cause every day to give in and agree.

‘Well that’s for you to say. You know what they are.’

‘I guess they can wait.’

He released the button and grabbed his storm jacket from the peg.

Outside the privacy of his room, in the open-plan office, the place was buzzing. All eighteen constables were on duty, leave cancelled, and what looked like most of them were milling round the operations board like they were waiting for something to happen on its own. It seemed like colour marker pens were more fun than getting out there and doing some police work.

Craig searched for Morris. He saw him sitting on the edge of a desk talking into a phone like he was a Hollywood theatrical agent, holding the phone beneath his chin and gesticulating to whoever was unfortunate enough to be on the other end with both hands. Not today, thought Craig. Today he couldn’t find the energy to play boss with this herd. Constable Daniel Hawk was at his desk studying the photos of Joe’s truck. Craig flicked him on the shoulder as he passed.

‘Going up to the pass to look round the site again. You want to get me up there in your Ford, constable?’

Daniel got up without speaking, put on his hat and followed his superior officer out into the car park.

The snow was getting silly now. Ploughs were doing their best, with the skiing traffic crawling behind them like ducklings after their mother, but it looked as if the snow would win by dark. Silver was going to be blocked off again. At least by road. A long discordant hoot from the distance sounded like the freight train on its way down the mountain was laughing at the cars. The tracks were clear now after the explosion, and those mile-long iron snakes of coal kept rolling through like nothing had happened. Daniel drove slowly and silently, accepting his place humbly in the line of cars.

Craig glanced across at him. ‘So how many colours have we managed to get on the wipe-clean?’

Daniel smiled. ‘We’re working on ten. But there’s still a debate about whether the truck driver should be pink or green.’

‘I wasn’t being funny, Hawk. I was expressing displeasure.’

‘I know, sir.’

Craig looked out the window, paused a while. ‘How are the guys coping with it? The fact it was Joe, I mean.’

Daniel made a little shrug, his eyes fixed on the white mess ahead. ‘They cope. You know. Angry I guess, but they figure we’ll get him.’

‘And you?’

‘The same.’

Daniel was putting up a defence shield. Craig could feel it, but he carried on.

‘Joe wasn’t seeing anyone else or anything, was he?’

‘Not to my knowledge. You knew him as well as me.’

‘Sure. But you bowled with him. He would have said if anything was wrong.’

Daniel took his eyes off the road for the first time, and shot his staff sergeant a look. The traffic slowed behind the plough in sympathy.

‘Why don’t you just say what’s on your mind, sir?’

‘And what’s that?’

‘That Joe was half-blood Cree and I’m full Kinchuinick, so we must have been best of buddies. That’s what you’re getting at isn’t it? The only Indians, even half-Indians, in the detachment, and we’re bound to stick together.’

Craig lowered his eyes. ‘Come on, Hawk. That’s not what I meant.’

‘I think it’s exactly what you meant. Sir.’

Daniel Hawk was right of course, but Craig wasn’t going to let his clumsy mishandling of the constable stand in the way of what he wanted to know. ‘Okay.’ He gave in softly, paused again, thinking. ‘I just wondered if there was anything cultural, anything particular to Native Canadians I wouldn’t know. Something that might have escaped me.’

Daniel Hawk continued to look straight ahead. Craig, over his embarrassment now, was starting to get annoyed. ‘Aw Christ, Hawk. I’m fucking sorry if it’s not politically correct to notice the fact that you and Joe happened to share some Indian blood.’

‘We didn’t. I repeat. He was half-Cree. I’m full Kinchuinick.’

‘Whatever. Quit acting like I just swindled Manhattan off you for a dollar and answer the question. Was there anything going on with Joe I should know about?’

Constable Hawk threw him that look again, then decided he’d turned the knife enough. He looked at last like he was thinking instead of brooding. ‘Nah. Nothing. He was pretty stable with Estelle and all. I didn’t notice anything weird.’

Hawk’s boss nodded solemnly. It was just as Craig thought. He’d have known if there had been anything wrong with his sergeant. It was just that niggling little maggot of insecurity that white cops have when dealing with Indians that made Craig even bring the topic up. He was sorry he had to. He never thought of Joe as anything but Joe. And whether Daniel Hawk believed it or not, he thought only of him as a damned good constable. So what that they’d been the only two Native Canadians in the detachment? The detachment also boasted one Sikh, a German and a half-Japanese. It was worth checking. Anything was worth checking. They had precious little else to go on.

Daniel drove on in silence but he was still thinking. Craig could practically hear the wheels turning in there.

‘What? There’s something. Isn’t there?’

Hawk shook his head. ‘Nah. It’s nothing about Joe. It’s the cultural bit that made me think of something.’

‘Tell me.’ Craig was hungry for it. Whatever it was.

Daniel looked grim, fighting to analyse whatever it was he’d conjured up.

‘Okay, like I say, it’s probably nothing. In fact, given the time involved it’s absolutely, definitely, nothing. But the way Joe died. It made me think of something else. That’s all.’

Craig turned his body towards Daniel. ‘Go on.’

‘I saw something like it. While I was policing on Redhorn. But it happened around twenty years ago.’

Craig tried to work it out. Daniel Hawk was only thirty-five years old, tops. How could he have presided over a murder at the tender age of fifteen? They were recruiting young into the Mounties, but not that young.

‘I don’t understand, Hawk. What do you mean you saw it?’

‘I said the murder happened over twenty years ago. That’s what the forensics guys came up with. We only found the mutilated remains of the body six years ago. It got dug up by some white construction guys who were pile-driving for the new rodeo centre. Course if it’d been found by Indians it would never have been reported. That’s the Kinchuinick way. Keeps the reserve a tight community. Makes police work almost impossible. The person, whoever it was, hadn’t even been reported missing.’

Craig tried to work this out. ‘So you uncovered an old body killed over two decades ago that was similar in its disfigurement to Joe’s injuries?’

‘Not similar. Identical.’

‘Indian?’

‘They couldn’t say for sure. No dental records or nothing.’ He looked across at Craig. ‘Contrary to popular white Canadian myth, we’re kinda the same as you under the skin.’

Craig ran a hand over his mouth, ignoring the dig. ‘Why didn’t you mention this?’

‘I only thought of it recently. I’ve been wondering if it’s relevant.’

Craig exhaled. ‘Fuck.’

‘Sorry. It just didn’t seem that important.’

‘Where are the Native Police files kept, Hawk? At Redhorn?’

‘Yeah. The Tribal Administrator keeps them, but since the Mounties from Stoke were called in they got them too.’

‘Remember the year?’

‘Sure. Larry was born that year. 1987.’

Craig drummed the dash impatiently, his desire to have that file on his knee right now, eating at him like a hunger. The traffic was as terrible as the snow. The tailback behind the plough stretched for at least a quarter of a mile, every vehicle apart from theirs revealing by their ski racks that they contained humans in the search for fun and thrills in this white stuff. Daniel looked across at him and read his discomfort.

‘You still want me to head for the site?’

‘No. Carry on to Stoke.’

Daniel nodded as if reprimanded and fixed his eyes on the road again. He wasn’t looking forward to seeing those photos again, but it served him right for bringing back the whole sorry affair. Maybe the Kinchuinick way was best. Maybe he should have kept his trap shut. But then he wasn’t really a Kinchuinick any more. He was a policeman.

Constable Benson, stamping his feet in the snow, raised a heavily-gloved hand to the Ford as they cruised past the taped-off site. Daniel waved back. It was wilderness up there. The Trans-Canada and the rail track sneaked over this high pass like intruders, as if they knew man had little right to be here and should think twice about leaving his mark. This was the highest point, and from here they could cruise all the way back down to Stoke, still trailing the city skiers as they slid about after the plough.

Craig had driven up and down here about two dozen times since the murder. If he was waiting for that movie-cop’s moment of divine inspiration he was going to have to wait a long time. Nothing about being there, about experiencing the physical presence of Wolf Pass and its inaccessibility to the pedestrian, lit a fire under his cold, empty ignorance.

This was new territory. There had only ever been one murder in his time in Silver. A pathetic, sad murder: a summer tourist battered to death in a rage by a drunk redneck from the mines up north, allegedly for insulting his girlfriend. Ugly and savage. Sylvia’s death had been neither. It had been what they described as peaceful. Craig disagreed. There was somehow more peace in brutality, a natural order where the ripping or tearing of flesh logically and visibly resulted in the escape of the human life-force from its prison of solid matter. The insidious creeping death in which the body was attacked from within was to him a thousand times more violent. He did not associate the hollow white cheeks of his once rosy-skinned wife with any form of peace.

When the doctor had told him, in that stupid pink-carpeted room in the hospital, full of plants and shit as if that made what got said in there any better, that Sylvia’s cancer was in the womb and that it would be a matter of days, he’d experienced a kind of elation. It was anger, and unimaginable grief, but it fired him up. He would go in there and get that cancer the way he went out and pulled in a thief. Yes, it would all be okay. Staff Sergeant Craig McGee to the rescue. We Always Get Our Man. Except you couldn’t arrest cancer. She’d died so doped up with morphine Craig doubted if she’d even known he was there. But he was. He held her cool thin hand as she let out one small breath and never took another. That was her death. Banal and pointless. He didn’t even call the nurse, just sat and looked at her, knowing it was over, that she’d gone. What was that garbage some writer said about not really dying, just going into another room? She was dead. There was, as far as Craig was concerned, no other room. This life was the only room there ever was, and Sylvia had left it and shut the door quietly behind her.

He envied Estelle Reader her grief. The grotesque and spectacular end to Joe’s life seemed to have a drama, a showmanship that gave it meaning. He could never say it to anyone, but he felt it. Sylvia’s death meant nothing to anyone but him, and even then it was more about his grief than her life. Lots of people died of cancer. The hospital in Calgary checked them in and out like library books, and nothing made those guys in white surgical trouser suits raise an eyebrow. But they would have raised an eyebrow if they’d seen Joe Reader. That made Joe’s death special and Sylvia’s ordinary, and sometimes Craig could hardly bear to think that anything about Sylvia could have been ordinary.

If anyone was ordinary it was him. At least he had been. Now though, he could hardly remember the thick-skinned unthinking cop he’d been for nearly two decades, letting the extraordinary events of life and death that were unavoidable in his job float past him as though he were immune. Not the kind of immunity that made him feel immortal. More as if he didn’t really notice he was alive. Taking things for granted. That time in Scotland, they’d walked on the beach in the Outer Hebrides and Sylvia had lain down on the cold wet sand, sifting through some shells. She’d picked ten tiny, delicate half-moon pink shells and laid them out in front of her.

‘Look. Babies’ fingernails.’

He’d crouched down behind her, his arms round her neck which was swathed in woollen scarves against the ridiculous weather, and looked at those beautiful fragile things.

She reorganized them earnestly, as though the order mattered. ‘Our baby will have tiny nails like that and you can bite them for him. Stop him scratching his face.’

Yes, he’d thought. That’s right. We will. No doubt about anything. The McGees were married, they would have children and they would grow old and proud of those children. That’s how life went.

Craig was not superstitious then and nor was he now, but the memory of the gust of wind that ripped across the sands on that huge, freezing, empty beach, came back to him often, the wet wind that had whipped away those paper-thin shells and made Sylvia laugh as she tried in vain to gather them up again. He thought about that a lot now. His life, no longer on those invisible oiled rails that carry a person through without having to ponder direction, was now as fragile as those shells. The wind would come, he knew, and swipe him away too. And what kind of wind would it be? Joe’s had been a hurricane. A huge, angry hurricane. That’s the way Joe went, and he was jealous. Joe, Joe, Joe. Must keep thinking about Joe.

The murder on the Redhorn reserve could be nothing or something. But he was anxious to know, and by the time they viewed the squat grey town of Stoke beneath them, he was bursting with impatience.

Daniel had been quiet throughout the journey, the pair of them sitting like eavesdroppers as the police radio occasionally spat out other people’s conversations. When he spoke, they had been silent for at least three-quarters of an hour.