Полная версия

Полная версияMythical Monsters

Cardan216 states that whilst he resided in Paris he saw five winged dragons in the William Museum; these were biped, and possessed of wings so slender that it was hardly possible that they could fly with them. Cardan doubted their having been fabricated, since they had been sent in vessels at different times, and yet all presented the same remarkable form. Bellonius states that he had seen whole carcases of winged dragons, carefully prepared, which he considered to be of the same kind as those which fly out of Arabia into Egypt; they were thick about the belly, had two feet, and two wings, whole like those of a bat, and a snake’s tail.

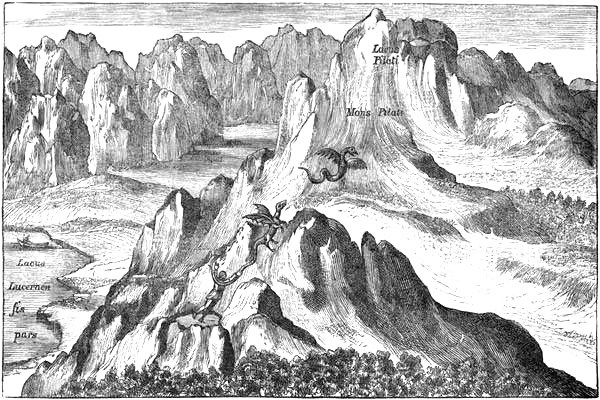

It would be useless to multiply examples of the stories, no doubt fables, current in mediæval times, and I shall therefore only add here two of those which, though little known, are probably fair samples of the whole. It is amusing to find the story of Sindbad’s escape from the Valley of Diamonds reappearing in Europe during the Middle Ages, with a substitution of the dragon for the roc. Athanasius Kircher, in the Mundus Subterraneus, gives the story of a Lucerne man who, in wandering over Mount Pilate, tumbled into a cavern from which there was no exit, and, in searching round, discovered the lair of two dragons, who proved more tender than their reputation. Unharmed by them he remained for the six winter months, without any other sustenance than that which he derived from licking the moisture off the rock, in which he followed their example. Noticing the dragons preparing for flying out on the approach of spring, by stretching and unfolding their wings, he attached himself by his girdle to the tail of one of them, and so was restored to the upper world, where, unfortunately, the return to the diet to which he had been so long unaccustomed killed him. In memory, however, of the event, he left his goods to the Church, and a monument illustrative of his escape was erected in the Ecclesiastical College of St. Leodegaris at Lucerne. Kircher had himself seen this, and it was accepted as an irrefragable proof of the story.

Fig. 39. – The Dragons of Mount Pilate.

(From the “Mundus Subterraneus” of Athanasius Kircher.)

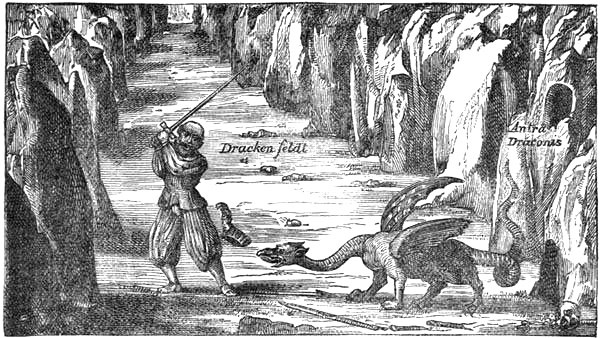

Another story is an account also given by A. Kircher,217 of the fight between a dragon and a knight named Gozione, in the island of Rhodes, in the year 1349 A.D. This monster is described as of the bulk of a horse or ox, with a long neck and serpent’s head – tipped with mule’s ears – the mouth widely gaping and furnished with sharp teeth, eyes sparkling as though they flashed fire, four feet provided with claws like a bear, and a tail like a crocodile, the whole body being coated with hard scales. It had two wings, blue above, but blood-coloured and yellow underneath; it was swifter than a horse, progressing partly by flight and partly by running. The knight, being solicited by the chief magistrate, retired into the country, when he constructed an imitation dragon of paper and tow, and purchased a charger and two courageous English dogs; he ordered slaves to snap the jaws and twist the tail about by means of cords, while he urged his horse and dogs on to the attack. After practising for two months, these latter could scarcely retain their frenzy at the mere sight of the image. He then proceeded to Rhodes, and after offering his vows in the Church of St. Stephen, repaired to the fatal cave, instructing his slaves to witness the combat from a lofty rock, and hasten to him with remedies, if after slaying the dragon he should be overcome by the poisonous exhalations, or to save themselves, in the event of his being slain. Entering the lair he excited the beast with shouts and cries, and then awaited it outside. The dragon appearing, allured by the expectation of an easy prey, rushed on him, both running and flying; the knight shattered his spear at the first onset on the scaly carcase, and leaping from his horse continued the contest with sword and shield. The dragon, raising itself on its hind legs, endeavoured to grasp the knight with his fore ones, giving the latter an opportunity of striking him in the softer parts of the neck. At last both fell together, the knight being exhausted by the fatigue of the conflict, or by mephitic exhalations. The slaves, according to instruction, rushed forward, dragged off the monster from their master, and fetched water in their caps to restore him; after which he mounted his horse and returned in triumph to the city, where he was at first ungratefully received, but afterwards rewarded with the highest ranks of the order, and created magistrate of the province.218

Fig. 40. – The Dragon of the Drachenfeldt. (Athanasius Kircher.)

Kircher had a very pious belief in dragons. He says: “Since monstrous animals of this kind for the most part select their lairs and breeding-places in subterraneous caverns, I have considered it proper to include them under the head of subterraneous beasts. I am aware that two kinds of this animal have been distinguished by authors, the one with, the other without, wings. No one either can or ought to doubt concerning the latter kind of creature, unless perchance he dares to contradict the Holy Scripture, for it would be an impious thing to say it when Daniel makes mention of the divine worship accorded to the dragon Bel by the Babylonians, and after the mention of the dragon made in other parts of the sacred writings.”

Harris, in his Collection of Voyages,219 gives a singular resumé. He says: – “We have, in an ancient author, a very large and circumstantial account of the taking of a dragon on the frontiers of Ethiopia, which was one and twenty feet in length, and was carried to Ptolemy Philadelphus, who very bountifully rewarded such as ran the hazard of procuring him this beast. – Diodorus Siculus, lib. iii… Yet terrible as these were they fall abundantly short of monsters of the same species in India, with respect to which St. Ambrose220 tells us that there were dragons seen in the neighbourhood of the Ganges nearly seventy cubits in length. It was one of this size that Alexander and his army saw in a cave, where it was fed, either out of reverence or from curiosity, by the inhabitants; and the first lightning of its eyes, together with its terrible hissing, made a strong impression on the Macedonians, who, with all their courage, could not help being frighted at so horrid a spectacle.221 The dragon is nothing more than a serpent of enormous size; and they formerly distinguished three sorts of them in the Indies, viz. such as were found in the mountains, such as were bred in caves or in the flat country, and such as were found in fens and marshes.

“The first is the largest of all, and are covered with scales as resplendent as polished gold.222 These have a kind of beard hanging from their lower jaw, their eyebrows large, and very exactly arched; their aspect the most frightful that can be imagined, and their cry loud and shrill;223 their crests of a bright yellow, and a protuberance on their heads of the colour of a burning coal.

“Those of the flat country differ from the former in nothing but in having their scales of a silver colour,224 and in their frequenting rivers, to which the former never come.

“Those that live in marshes and fens are of a dark colour, approaching to a black, move slowly, have no crest, or any rising upon their heads.225 Strabo says that the painting them with wings is the effect of fancy, and directly contrary to truth, but other naturalists and travellers both ancient and modern affirm that there are some of these species winged.226 Pliny says their bite is not venomous, other authors deny this. Pliny gives a long catalogue of medical and magical properties, which he ascribes to the skin, flesh, bones, eyes, and teeth of the dragon, also a valuable stone in its head. ‘They hung before the mouth of the dragon den a piece of stuff flowered with gold, which attracted the eyes of the beast, till by the sound of soft music they lulled him to sleep, and then cut off his head.’”

I do not find Harris’s statement in Diodorus Siculus, the author quoted, but there is the very circumstantial description of a serpent thirty cubits (say forty-five feet) in length, which was captured alive by stratagem, the first attempt by force having resulted in the death of several of the party. This was conveyed to Ptolemy II. at Alexandria, where it was placed in a den or chamber suitable for exhibition, and became an object of general admiration. Diodorus says: “When, therefore, so enormous a serpent was open for all to see, credence could no longer be refused the Ethiopians, or their statements be received as fables; for they say that they have seen in their country serpents so vast that they can not only swallow cattle and other beasts of the same size, but that they also fight with the elephant, embracing his limbs so tightly in the fold of their coils that he is unable to move, and, raising their neck up underneath his trunk, direct their head against the elephant’s eyes; having destroyed his sight by fiery rays like lightning, they dash him to the ground, and, having done so, tear him to pieces.”

In an account of the castle of Fahender, formerly one of the most considerable castles of Fars, it is stated – “Such is the historical foundation of an opinion generally prevalent, that the subterranean recesses of this deserted edifice are still replete with riches. The talisman has not been forgotten; and tradition adds another guardian to the previous deposit, a dragon or winged serpent; this sits for ever brooding over the treasure which it cannot enjoy.”

I shall examine, on a future occasion, how far those figures correspond to the Persian ideas of dragons and serpents, the azhdaha (اژدها = dragon) and már (مار = snake), which, as various poets relate, are constant guardians of every subterraneous ganj (گنج = treasure).

The már at least may be supposed the same as that serpent which guards the golden fruit in the garden of the Hesperides.

CHAPTER VII.

THE CHINESE DRAGON

We now approach the consideration of a country in which the belief in the existence of the dragon is thoroughly woven into the life of the whole nation. Yet at the same time it has developed into such a medley of mythology and superstition as to materially strengthen our conviction of the reality of the basis upon which the belief has been founded, though it involves us in a mass of intricate perplexities in connection with the determination of its actual period of existence.

There is no country so conservative as China, no nation which can boast of such high antiquity, as a collective people permanently occupying the same regions, and preserving records of their polity, manners, and surroundings from the earliest date of their occupation of the territory which still remains the centre of their civilization; and there is none in which dragon culture has been more persistently maintained down to the present day.

Its mythologies, histories, religions, popular stories, and proverbs, all teem with references to a mysterious being who has a physical nature and spiritual attributes. Gifted with an accepted form, which he has the supernatural power of casting off for the assumption of others, he has the power of influencing the weather, producing droughts or fertilizing rains at pleasure, of raising tempests and allaying them. Volumes could be compiled from the scattered legends which everywhere abound relating to this subject; but as they are, for the most part, like our mediæval legends, echoes of each other, no useful purpose would be served by doing so, and I therefore content myself with drawing, somewhat copiously, from one or two of the chief sources of information.

As, however, Chinese literature is but little known or valued in England, it is desirable that I should devote some space to the consideration of the authority which may be fairly claimed for the several works from which I shall make quotations, bearing on the Chinese testimony of the past existence, and date of existence, of the dragon and other so-called mythical animals.

Incidental comments on natural history form a usual part of every Chinese geographical work, but collective descriptions of animals are rare in the literature of the present, and almost unique in that of the past. We are, therefore, forced to rely on the side-lights occasionally afforded by the older classics, and on one or two works of more than doubtful authenticity which claim, equally with them, to be of high antiquity. The works to which I propose to refer more immediately are the Yih King, the Bamboo Books, the Shu King, the ’Rh Ya, the Shan Hai King, the Păn Ts’ao Kang Muh, and the Yuen Kien Léi Han.

As it is well known that all the ancient books, with the exception of those on medicine, divination, and husbandry, were ordered to be destroyed in the year B.C. 212 by the Emperor Tsin Shi Hwang Ti, under the threatened penalty for non-compliance of branding and labour on the walls for four years, and that a persecution of the literati was commenced by him in the succeeding year, which resulted in the burying alive in pits of four hundred and sixty of their number, it may be reasonably objected that the claims to high antiquity which some of the Chinese classics put forth, are, to say the least, doubtful, and, in some instances, highly improbable.

This question has been well considered by Mr. Legge in his valuable translation of the Chinese Classics. He points out that the tyrant died within three years after the burning of the books, and that the Han dynasty was founded only eleven years after that date, in B.C. 201, shortly after which attempts were commenced to recover the ancient literature. He concludes that vigorous efforts to carry out the edict would not be continued longer than the life of its author – that is, not for more than three years – and that the materials from which the classics, as they come down to us, were compiled and edited in the two centuries preceding the Christian era, were genuine remains, going back to a still more remote period.

The “Yih King” or “Yh King.”The Yih King is one of those books specially excepted from the general destruction of the books. References in it to the dragon are not numerous, and will be found as quotations in the extracts from the large encyclopædia Yuen Kien Léi Han, given hereafter. This work has hitherto been very imperfectly understood even by the Chinese themselves, but the recent researches of M. Terrien de la Couperie lead us to suppose that our translations have been imperfect, from the fact that many symbols have different significations in the present day to those which they had in very ancient times, and that a special dictionary of archaic meanings must be prepared before an accurate translation can be arrived at, a consummation which may shortly be expected from his labours. I find in my notes, taken from the manuscript of a lecture given before the Ningpo Book Club in 1870, by the Rev. J. Butler, of the Presbyterian Mission, that “the way in which the dragon came to represent the Emperor and the Throne of China227 is accounted for in the Yih King as follows: – The chief dragon has his abode in the sky, and all clouds and vapours, winds and rains are under his control. He can send rain or withhold it at his pleasure, and hence all vegetable life is dependent on him. So the Emperor, from his exalted throne, watches over the interests of his people, and confers on them those temporal and spiritual blessings without which they would perish.” I abstain from dwelling on this or any other passages in the Yih King, pending the translation promised by M. De la Couperie, the nature of whose views on it are condensed in the note228 attached, being extracts from his papers on the subject.

The Annals of the Bamboo BooksThese are annals from which a great part of Chinese chronology is derived. Mr. Legge gives the history of their discovery, as related in the history of the Emperor Woo, the first of the sovereigns of Tsin, as follows:

“In the fifth year of his reign, under title of Hëen-ning229 [= A.D. 279], some lawless parties, in the department of Keih, dug open the grave of King Sëang of Wei [died B.C. 295] and found a number of bamboo tablets, written over, in the small seal character, with more than one hundred thousand words, which were deposited in the imperial library.”

Mr. Legge adds, “The Emperor referred them to the principal scholars in the service of the Government, to adjust the tables in order, having first transcribed them in modern characters. Among them were a copy of the Yih King, in two books, agreeing with that generally received, and a book of annals, in twelve or thirteen chapters, beginning with the reign of Hwang-te, and coming down to the sixteenth year of the last emperor of the Chow dynasty, B.C. 298.”

“The reader will be conscious of a disposition to reject at once the account of the discovery of the Bamboo Books. He has read so much of the recovery of portions of the Shoo from the walls of houses that he must be tired of this mode of finding lost treasures, and smiles when he is now called on to believe that an old tomb opened and yielded its literary stores long after the human remains that had been laid in it had mingled with the dust. From the death of King Sëang to A.D. 279 were 574 years.”

Against this, however, which is not a very weighty objection, if we consider the length of time that Egyptian papyri have been entombed before their restoration to the light, Mr. Legge ranges preponderating evidence in favour of their authenticity, and concludes that “they had, no doubt, been lying for nearly six centuries in the tomb in which they had been first deposited when they were then brought anew to light.”

The annals consist of two portions, one forming what is undoubtedly the original text, and consisting of short notices of occurrences, such as, “In his fiftieth year, in the autumn, in the seventh month, on the day Kang shin [fifty-seventh of cycle] phœnixes, male and female, arrived,” &c. &c. It also records earthquakes, obituaries, accessions, and remarkable natural phenomena. The other portion is interspersed between these, in the form of rather diffuse, though not very numerous, notes, which by some are supposed to be a portion of the original text, by others, to have been added by the commentator Shin Yo [A.D. 502-557].

In the latter, frequent references are made to the appearance of phœnixes (the fung wang), ki-lins (unicorns), and dragons.

In the former we find only incidental references to either of these, such as, “XIV. The Emperor K‘ung-kea. In his first year (B.C. 1611), when he came to the throne, he dwelt on the west of the Ho. He displaced the chief of Ch‘e-wei,230 and appointed Lew-luy231 to feed the dragons.”

According to the latter, Hwang Ti (B.C. 2697) had a dragon-like countenance; while the mother of Yaou (B.C. 2356) conceived him by a dragon. The legend is: “After she was grown up, whenever she looked into any of the three Ho, there was a dragon following her. One morning the dragon came with a picture and writing. The substance of the writing was – the Red one has received the favour of Heaven… The red dragon made K‘ing-teo pregnant.”

Again, when Yaou had been on the throne seventy years, a dragon-horse appeared bearing a scheme, which he laid on the table and went away.

The Emperor Shun (B.C. 2255) is said to have had a dragon countenance.

It is also said of Yu (the first emperor of the Hia dynasty) that when the fortunes of Hia were about to rise, all vegetation was luxuriant, and green dragons lay in the borders; and that “on his way to the south, when crossing the Kiang, in the middle of the stream, two yellow dragons took the boat on their backs. The people were all afraid; but Yu laughed, and said, ‘I received my appointment from Heaven, and labour with all my strength to nourish men. To be born is the course of nature; to die is by Heaven’s decree. Why be troubled by the dragons?’ On this the dragons went away, dragging their tails.”

From these extracts it will be seen that the dragon, although universally believed in, was already mythical and legendary, so far as the Chinese were concerned.

The “Shu King”232 or “Shoo King”is, according to Dr. Legge, simply a collection of historic memorials, extending over a space of one thousand seven hundred years, but on no connected method, and with great gaps between them.

It opens with the reign of Yaou (B.C. 2357), and contains interesting details of the polity of those remote ages.

It contains a record of the great inundation occurring during his reign, which Mr. Legge does not identify with the Deluge of Genesis, but which Dr. Gutzlaff and other missionary Sinologues consider to be the same.

It is interesting to find in this work, claiming so high an antiquity, references to an antiquity which had preceded it – a bygone civilization, perhaps – as follows, in the book called Yih and Ts‘ih.233 The emperor (Shun, B.C. 2255 to 2205) says, “I wish to see the emblematic figures of the ancients – the sun, the moon, the stars, the mountain, the dragon, and the flowery fowl, which are depicted on the upper garment; the temple cup, the aquatic grass, the flames, the grains of rice, the hatchet, and the symbol of distinction, which are embroidered on the lower garment. I wish to see all these displayed with the five colours, so as to form the official robes; it is yours to adjust them clearly.” Here the dragon is chosen as an emblematic figure, in association with eleven others, which are objects of every-day knowledge, and this, I think, establishes a presumption that it itself was not at that date considered an object of doubtful credibility.

Similarly, we find the twelve symbolical animals, representing the twelve branches of the Horary characters (dating, see Williams’ Dictionary, from B.C. 2637), to be the rat, the ox, tiger, hare, dragon, serpent, horse, sheep, monkey, cock, dog, boar, where the dragon is the only one about whose existence a question can be raised. From this latter we learn that there was no confusion of meaning then between dragons and serpents; the distinction of the two creatures was clearly recognized, just as it was many centuries afterwards by Mencius (4th century B.C.), who, in writing of these early periods, says, “In the time of Yaou, the waters, flowing out of their channels, inundated the Middle Kingdom. Snakes and dragons occupied it, and the people had no place where they could settle themselves”; and again, “Yu dug open their obstructed channels, and conducted them to the sea. He drove away the snakes and dragons,234 and forced them into the grassy marshes.”

The “’Rh Ya.”The ’Rh Ya or Urh Ya,235 also transliterated Eul Ya and Œl Ya, a dictionary of terms used in the Chinese classics, but more especially of those in the Shi King, or “Book of Odes,” a collection of ancient ballads compiled and arranged by Confucius.

There is a tradition that it was commenced by the Duke of Chow 1100 B.C., and completed or enlarged by Tsz Hia, a disciple of Confucius.

Dr. Bretschneider suggests that each heading or phrase in the original book merely represents the book names and the popular names of the plants and animals.

The bulk of the work at present extant consists of the commentary by Kwoh P‘oh (about A.D. 300) and, in some editions, of additional commentaries by other authors.

The illustrations selected from it for the present volume are reduced from those in a very fine folio copy, for the loan of which I am indebted to Mr. Thomas Kingsmill, of Shanghai.

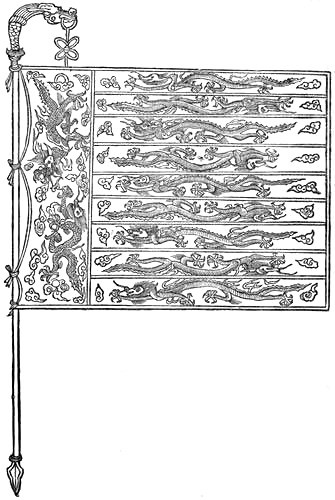

Fig. 41. – The Banner called Tsing K’i.

(From the ’Rh Ya.)

These profess to date back so far as the Sung dynasty (A.D. 960 to A.D. 1127), and it is interesting to observe that the representations of tools of husbandry then in use (Fig. 50, p. 232), and of the methods of hawking (Fig. 46, p. 225), fishing (Fig. 47, p. 227), and the like, are such as might be taken without alteration from those of the present day.