Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Pastoral Days; or, Memories of a New England Year

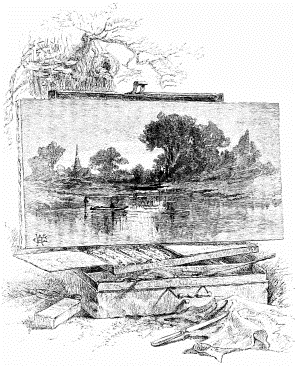

Now we confront a rude slab fence, an ancient landmark, that terminates its length at the edge of the stream, where its gray and crumbling boards are secured with rusty nails against the trunk of a tall buttonwood-tree. A loosened slab is easily found, and we are soon upon the other side; and after picking our way through a forest of bush-elders, we emerge upon an open lot of low flat pasture-land, known always as the “old swamp meadow.” No other five acres on the face of the earth are so dear to me as this neglected field. I know its every rise and fall of ground, its every bog, and its lush greenness is refreshing even to the thought.

It is a luxuriant garden of all manner of succulent and juicy vegetation; an outbursting extravagance of plant life of almost tropical exuberance. All New England’s most majestic and ornamental flora seem congregated in its congenial soil; and even when a boy I learned to know and love them all, and even call them by their names.

Here are towering stems of iron-weed lifting high their scattered purple crowns, and in their midst the woolly clumps of boneset, its white flowered cushions intermingling with the dense pink tufts of thorough-wort.

On every side we overlook whole patches of these splendid blossoms, with their crests closely crowded in a mosaic of pink and white. And here’s a bed of peppermint and spearmint, interspersed with flaming spikes of cardinal lobelia; and here a lusty plant of Indian mallow, entangled in a maze of gold-thread and smart-weed. Here are massive burdocks six feet high, and great trees of jimson-weed, with their large spiral flowers and thorny pods.

High fronds of chain-fern rise up on every side from a jungle of bur-marigolds and clotburs, and tear-thumbs, with their saw-toothed stems and tiny bunches of pink blossoms.

No inch of ground in the old swamp lot but which does its tenfold duty; and what it lacks in quality of produce it amply makes up in quantity. Even a neighboring bed of clean-washed gravel is overrun with creeping mallow, with its rounded leaves and little “cheeses” down among their shadows.

EVEN-TIDE.

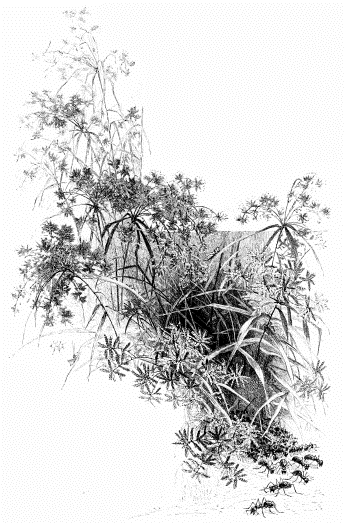

Farther on we see the lily-pond, with its surrounding swamp and its legion of crowded water-plants. Here are rank, massive beds of swamp-cabbage, and lofty cat-tails by the thousand among the bristling bogs of tussock-sedge and bulrush. Here are calamus patches, and alder thickets, and sedges without number; and the prickly carex and blue-flag abound on every side. There are galingales and reeds, and tall and graceful rushes, turtle-head and jointed scouring grass, and horse-tail, besides a host of other old acquaintances, whose faces are familiar, but whose names I never knew. But they were all my friends in boyhood. I knew them in the bud and in the blossom, and even in their winter skeletons, brown and broken in the snow. Near by there is a ditch: you never would know it, for it is completely hidden from view beneath an interlacing growth of jewel-weed. But see that gorgeous mass of deep scarlet that floods the farther bank! Nowhere within a circuit of miles around is there such a regal display of cardinal flowers as this: skirting the borders of the ditch for rods and rods, clustering about a ruined, tumbling fence, whose moss-grown pickets are almost hidden in the dense profusion of bloom.

Then there is its airy companion, the “touch-me-not,” with its translucent, juicy stem, and its queer little golden flowers with spotted throats – the “jewel-weed” we used to call it. I know not why, unless from the magic of its leaf, which, when held beneath the water, was transformed to iridescent frosted silver. We all remember its sensitive, jumping seed-pods, that burst even at our approach for fear that we should touch them; but no one can fully appreciate the beauty of the plant who has not seen its silvery leaf beneath the water. Here it justifies its name, for it is indeed a jewel.

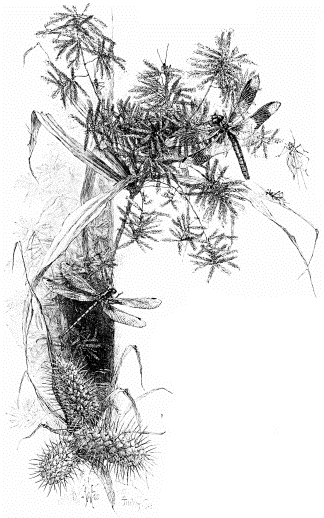

How often in those olden times have I lain down among these bulrushes and sedges near the lily pond, and listened to the buzzing songs of the crickets and the tiny katydids that swarmed the growth about me, and filled the air with their incessant din. I remember the little colony of ants that picked their way among the rushes; that gauzy dragon-fly too, that circled and dodged about the water’s edge, now skimming close upon the surface, now darting out of sight, or perhaps alighting on an overhanging sedge, as motionless as a mounted specimen, with wings aslant and fully spread. “Devil’s darning-needles” they were called. The devil may well be proud of them; for darning-needles of such precious metals and such exquisite design are rare indeed. They were of several sizes too. Some were large, and flashed the azure of the sapphire; others fluttered by with smoky, pearly wings, and slender bodies glittering in the light like animated emeralds: and another I well remember, a little airy thing, with a glistening sunbeam for a body, and wings of tiny rainbows.

I remember how I watched the disturbed motion of the arrow-heads out in the water, as the cautious turtles worked their way among them, and crawled out upon the stump close by.

Here they huddled together, a dozen or more, with heads erect, and turning from side to side as they surveyed the surrounding carpet of lily-pads, or listened to the bass-drum chorus of the great green bull-frogs among the pickerel-weed; and when I jumped and yelled at them, what a rolling, sprawling, splashing in the mud! It fairly makes me laugh to think of it. But there is hardly a leaf or wisp of grass in this old swamp lot but what brings back some old association or pleasant reminiscence.

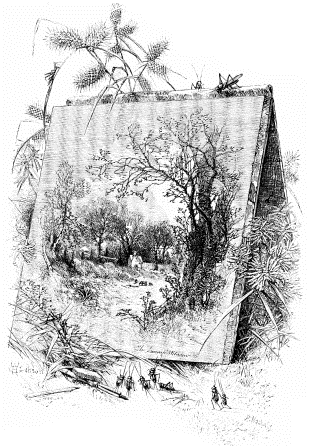

For a week thus we idled, now on the mountain, now in the meadow, while I, with my sketch-book and collecting-box, either whiled away the hours with my pencil, or left the unfinished work to pursue the tantalizing butterfly, or search for unsuspecting caterpillars among the weeds and bushes.

SOME ART CONNOISSEURS.

PROFESSOR WIGGLER.

On a sprig of black alder I found one – the same little fellow as of old, afflicted with the peculiarities of all his progenitors. We used to call him “Professor Wiggler,” owing to an hereditary nervous habit of wiggling his head from side to side when not otherwise employed. To this little humpbacked creature I am indebted for a great deal of past amusement. Distinctly I remember the whack-whack-whack on the inside of the old pasteboard box as the captive pets threatened to dash out their brains in their demonstrations at my approach. Professor Wiggler is really a most remarkable insect, as one might readily imagine from his scientific name, for in learned circles this individual is known as Mr. Gramatophora Trisignata. He has many strange eccentricities. At each moult of the skin he retains the shell of his former head on a long vertical filament. Two or three thus accumulate, and, as a consequence, in his maturer years he looks up to the head he wore when he was a youngster, and ponders on the flight of time and the hollowness of earthly things, or perhaps congratulates himself on the increased contents of his present shell. When fully grown, he stops eating, and goes into a new business. Selecting a suitable twig, he gnaws a cylindrical hole to its centre and follows the pith, now and then backing out of the tunnel, and dropping the excavated material in the form of little balls of sawdust. At length he emerges from the hollow, and again drawing himself in backward, spins a silken disk across the opening, and tints it with the color of the surrounding bark. Here he spends the winter, and comes out in a new spring suit in the following May. Only recently I had in my possession several of these twigs with their enclosed caterpillars, and in every one the color of the silken lid so closely matched the tint of the adjacent bark, although different in each, that several of my friends, even with the most careful scrutiny, failed to detect the deceptive spot. Whether the result of chance or of the instincts of the insect, I do not know; but certain it is that he paints with different colors under varying circumstances.

Insect-hunting had always been a passion with me. Large collections of moths and butterflies had many times accumulated under my hands, only to meet destruction through boyish inexperience; and even in childhood the love for the insect and the passion for the pencil strove hard for the ascendency, and were only reconciled by a combination which filled my sketch-book with studies of insect life.

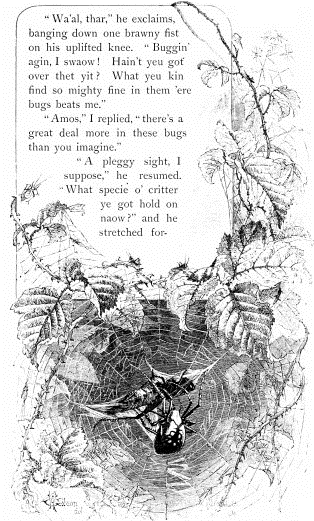

There was one inhabitant of our fields which had always been to me a never-failing source of entertainment. There he is, the gilded tyrant. I see him now swinging to and fro on his glistening nest of silken threads, his golden yellow form glowing in bold relief against the dark recess in the brambles. My sketch is left in the grass, and I am soon seated in front of the gossamer maze. A festive grasshopper jumps up into my face, and makes a carom on the web. With a spasmodic snap of one hind leg he extricates it from its entanglement, and in another instant would fall from the meshes; but the agile spider is too quick for him. With a movement so swift as almost to elude the eye, he draws from his body a silver cloud of floss, and with his long hind legs throws it over his captive. The head and tail of the grasshopper are now further secured, after which the spider carefully straddles around the struggling insect, and bites off the other radiating webs in close proximity. The unlucky prey now hangs suspended across the opening. With business-like coolness his tormentor dangles himself from the edge of the torn web, and another cataract of glistening floss is thrown up and attached to the under side of the prisoner, after which he is turned round and round, as if on a spit. The stream of floss is carried from head to foot, and in less time than it takes to describe it the victim is wrapped in a silken winding-sheet, and soon meets his death from the poisoned fangs of his captor. Here is but one of the thousands of tragedies that are taking place every hour of the day in our fields. While deeply interested in the closing scenes of this one, I suddenly become aware of a shadow passing over the bushes. I turn my head, and meet the puzzled and pleasant gaze of Amos Shoopegg, as he stands there, hands in pockets, and milk-pail swinging from his wrist.

THE TYRANT OF THE FIELDS.

ward his fringed and weather-beaten neck, and peered over the brambles. “What is’t ye got thar – straddle-bug?” He came still nearer, and looked at the spider. “Wa’al, darn my pictur ef ’tain’t an old yeller-belly! P’r’aps you don’t know that them critters is pizen. Why, Eben Sanford’s gal got all chawed up by one on ’em. Great Sneezer!” he exclaimed, taking three or four strides backward, with both hands uplifted. I had merely raised my hand and gently smoothed the spider.

“Wa’al,” he continued, “yen kin rub ’em daown ef yeu pleze; but fer my part, I’d ruther keep off abaout a good spittin’ distance” – which was the Shoopegg way of expressing a length of about fifteen feet. Amos was crossing lots for his “caow,” he said; but in spite of his plea that the “old heiffer” was “bellerin’” like “Sam Hill,” and was “gittin’ ’tarnal on-easy,” I made him tarry sufficiently long to enable me to send him off a wiser man.

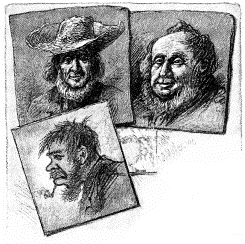

Amos Shoopegg is a type of a large class of the native element of Hometown. Of course, “Shoopegg” is not his actual name. In the long line of his prided Puritan ancestry no one ever bore it before him. This is only an affectionate epithet given him by the village boys full twenty years ago, and it has stuck to him closer than a brother ever since, as those festive surnames always do. Nominally, Amos was a farmer. In summer he was one in fact, and could swing off as pretty a swath in haying as any man in town. But in the winter he changed his vocation, and became a disciple of the “waxed-end.” All day long he could be seen, closeted with a little red-hot stove, plying his trade in his small, square shop, up near the old red school-house. Here he pounded on the big lapstone on his knees, or, with strap and foot-stick in position, punched and tugged around the edge of those marvellous brogans. He made slings and leather “suckers” for the boys, and furnished them with all the black-wax they could chew – or stow-away, to stick between the lining of their pockets. And the huge wooden shoe-pegs that he drove beneath his hammer were a sight to behold. The man who used his “cheap line of goods” might verily say he walked upon a wood-pile.

So they dubbed him “Shoe-peg,” or “Shoop” for brevity. There are others among his neighbors who would furnish an inexhaustible source of study to the student of character. There’s old Rufus Fairchild, known as “Roof,” a rotund specimen of rural jollity, his round face set in dishevelled locks of gray, with a twinkle in his eye and a good word for everybody. And there’s Father Tomlinson, who keeps the post-office down by the dam, as genial an old fellow as ever wrapped up his throat in a white stock. And I might almost continue the list indefinitely. But there is one I must especially mention; and, now that I think of it, he really should have headed the list, for he stands alone – or at least he does sometimes. If you are in search of the embodiment of typical Erin, you need go no farther; here he is. This individual represents another nationality which swells the population of Hometown – the hard-working laborers who toil in the great factory down in the glen, called “Satan’s Misery.” The above personage is one of the best-hearted creatures in the town; but it is the old story, and the world to him is enclosed in the compass of a barrel-hoop. When last I saw him he was in an evident decline, but as I put my finger on his wrist I could still feel the pulsations of the whiskey coursing through his veins.

“Look here, my good fellow,” I said to him one day, “why don’t you taper off a little? If you keep on in this way, you’ll be in your grave in less than a month. How would you like that?”

“Arrah, begorra,” he replied, with a look of hopeful resignation, “if I cud awnly be shure o’ me gude skvare dthrink in the other wurrld, oi wudn’t moind.”

The record of a single evening spent in the village store, with its rural jargon and homespun yarns, its odd vernacular and rustic gossip, would make a volume as rare and unique as the characters it would depict.

The store itself is a matchless picture in its way, and for variety in accessory is as rich as could be wished for. The low, murky ceiling, hung with all manner of earthly goods – scythes and rakes, boots and pails, in pendulous array; bottles and boxes, brooms and breast-pins, are here – in short, everything that heart could wish or thought suggest, from speckled calicoes to seven-cent sugar, or from a three-tined fork to a goose-yoke. Evening after evening, for an hour or so, I was tempted thither, until I found the week had gone. Sunday came again – Sunday in New England. The old bell swung on its wheel in the belfry, ringing out its call to devotion, and ere the echo had died in the recesses of the mountain beyond the still atmosphere reverberated with an answering peal from the little sister church in the valley below, as the scattered groups with strolling steps wend their way to “meeting,” and the gay loads from Newborough go flitting by on the accustomed Sunday drive.

Monday dawned on Hometown. It found me up and doing. I had enjoyed one week of glorious loafing, but work was the programme for the next. I went to Draper’s Inn and engaged a horse and buggy “until further notice.” “A spang-up team” he called it, and it would be up “in half a jiffy.” We were waiting for it when it came, and what with our variety of luggage in the shape of canvases, color-boxes, hammocks, camp-seats, and easels, every bit of available space in that buggy was well utilized. Before the clock has struck nine, we are spinning along down through the village, now past the store, now over the bridge, and turning to the right, we glide by the little post-office, as the kind face of Father Tomlinson nods a “good-bye” from the door-way.

A little farther, and we have left the little slope-roofed school-house in our path, and are soon ascending the long hill of Zoar, from which we look back four miles to the cliff and nestling town. In ten minutes more we approach the brow of a steep declivity, and the broad Housatonic opens up to view, winding off into the misty mountains in the distance. There is now a drive of half a mile along the side of a wild mountain-slope, where mountain-laurels grow in wild profusion, and the rooty, overhanging banks are tufted with rich green moss, overgrown with checker-berries and arbutus. The river roars far down below us, and for a few minutes our eyes feast on as lovely an extent of varied New England landscape as is easily found. And yet this is only a short section of one of the many matchless drives that follow the course of this beautiful river around the borders of Hometown.

FAMILIAR FACES AT THE VILLAGE STORE.

Suddenly we leave the stream as it glides away on an abrupt turn beneath the crescent of a rocky precipice, and before we have fairly lost the sound of the ripples we have arrived at our journey’s end. A pair of bars under an old butternut-tree mark the place. The carriage is backed to the side of the road, and the horse turned loose in the rocky meadow. This is Joab Nichols’s “pasture lot,” with fodder consisting principally of huge boulders, hardhack, and spleenwort; to be sure, with a stray relish of “butter-and-eggs” here and there, and a thousand white saucers of wild carrot handy to go with them. One or two trips across the field bring all our luggage, and we are soon enjoying cool comfort in the hemlock shade of a fairy grotto. Above us the babbling brook bounds and splashes over mossy rocks, disappearing in a mass of creamy foam, from under which it eddies toward us only to plunge twenty feet into a miniature cañon below. Again, yonder it bubbles into a whirling pool, where the bordering ferns bend and nod above its buoyant surface; and now gliding from view beneath the tangle of drooping boughs, it disappears only to burst forth once more in its merry song as it rushes over the rapids.

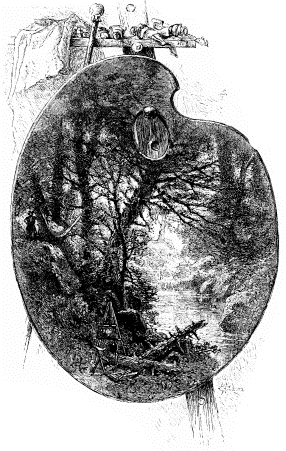

“I chatter, chatter as I go,To join the brimming river;For men may come and men may go,But I go on forever.”Here in this wild retreat I have found my sylvan studio – shut in by fringed and fragrant evergreens, enlivened by the undergrowth of feathery fronds, and the shimmer of the beech, as the tracery of overhanging boughs trembles in the gentle breeze. Day after day finds us in this little paradise, and as one in luxurious hammock swings away the hours, now lost in fiction, now in short repose, or perhaps with busy needle fashions graceful figures in Kensington design, the canvas on the easel shows a fortnight’s constant care, and the palette changes to a keepsake of a sunny memory – a tinted souvenir.

For two weeks the gurgling brook sang to us in this wild retreat. As evening after evening closed in upon us, the unfinished pictures were stowed away in horizontal crevices between the rocks, and, with hammock still swinging in the trees, we left the gloom to the hooting owl, that evening after evening, with tremulous cry, proclaimed the twilight hour from the tall hemlock overhead. Ere long the murmuring Housatonic shimmers below us in the moonlight as we hurry on our homeward way, and the distant lights of Hometown are soon seen glimmering; through the evening mist. The old bridge now rumbles through the darkness its signal of our return, and the host of Draper’s Inn is seen awaiting us at the illumined door-way. A quiet, cosy supper, and in the rays of a gleaming lantern, held aloft to light our path, we follow our lengthening shadows to the old front gate. Repeat this day’s record fourteen times, and you have the sum of a happy experience, with but one drawback: it had an end – an end that would have left its reaction, were it not for the store of increased pleasure that awaited us for the few closing days of our pilgrimage – for me, at least, although in other scenes, its climax.

A SOUVENIR.

Many like me are happy in the possession of a dear old homestead; but there are few, I ween, who enjoy the blessing of a double inheritance such as has been my lot – two homes which share my equal devotion, two homes without a choice; the one this beloved heirloom in Hometown, and the other – But you shall see. We shall be there soon, for the little satchel is packed, and the carriage awaits us at the gate. A drive of eighteen miles is before us – a beautiful series of pictures. Down through the village, past the old red mill and smithy, with its ringing anvil, and we are soon winding our way through a sombre glen. Presently we catch glimpses of the great rumbling factory, with its clouds of smoke and steam melting into the wooded mountain above. The old yellow bridge now creaks under our approach, and ere we are aware a sudden turn leads us out of a wilderness on to the shore of the beautiful Housatonic. For a few minutes the rushing water trickles through the wheels as over jolting stones our pony leads us through the ford, and, refreshed by the cool bath, makes a lively sally up the eastern bank. For ten miles the Housatonic guides us around its winding curves through a path of ever-changing beauty, now shut in by the dense, dark evergreens, and again emerging into a bower of silvery beeches, where the roadway is carpeted with mottled shadows, and the dappled trunks flicker with the softened glints of sunlight. Here we come upon a sandy stretch where the road is sunken between two sloping banks thick-set with mulleins and sweet-fern, and overrun with creeping brambles. The stone-wall above is wreathed in trailing woodbine, and along its crest we see the swaying tips of wheat from the edge of the field just beyond; and here we pass a border of whortleberry bushes, laden with their fruit. Now it is a hazel thicket crowding close upon our wheels, and among the leaves we see the brown, tanned husks of the ripening nuts, almost ready for that troop of boys and girls that you may be sure are watching and waiting for them.

The old gray toll-bridge soon nears to view, with its two long spans and fantastic beams. Farther on, peering from its willows, stands the ruined cider-mill, with its long moss-grown lever jutting through the trees – an old-time haunt, now crumbling in decay. But we only catch a glimpse of it, for in a moment more we are shut in beneath another bower of beeches and white birches, where the road takes a steep ascent, and the rippling river sends up its sunny reflections among the leaves and tree-trunks. When once more upon a level, it is to look ahead through a long avenue of shade – a leafy canopy two miles in length – with only an occasional break to open up some charming bit of landscape across the water. In these two miles of umbrage you may see types of almost every tree that grows within the boundaries of New England. Old veteran beeches are here, their trunks disfigured with scars that once were names cut in the bark. Here are spots that look like half obliterated figures; and here are spreading hieroglyphs that tell, perhaps, of old-time vows plighted at the trysting-tree; and here’s a semblance of a heart, a broken heart indeed, if its present form be taken as a prophetic symbol.

ALONG THE HOUSATONIC.

There are magnificent rock-maples too, and silver-maples that shake down their little swarms of winged seeds. Tulip-trees and spotted buttonwoods grow side by side, and quivering aspens and white poplars are seen at every clearing. There are yellow birch-trunks frayed out with the wind, and great snake-like stems of grape-vine, that twist and writhe among the branches of the trees. There are hop hornbeams, and chestnuts, and – But there is no need to enumerate them all. Just think of every New England tree you ever knew, and add a score besides, and you will form a slight idea of the varied verdure that hems in this charming Housatonic drive, with its rocky roadside embroidered in trickling moss and fumitory; and rose-flowered mountain-raspberry growing so close upon the road that your pony takes a wayward nip, and plucks its blossomed tip as he passes.