Полная версия

Полная версияPrivate Letters of Edward Gibbon (1753-1794) Volume 2 (of 2)

LORD SHEFFIELD'S OFFER FOR NEWHAVEN.

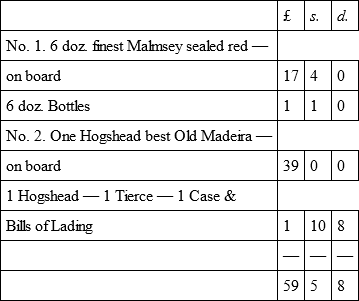

We almost howled when we read the tremendous account of nearly five months' confinement – the weakness in your traces affrighted me most, but I rejoiced exceedingly in your last, which says that you have advanced to nearly your usual condition of strength. I never heard of Pyrmont waters for the gout – but I grieve to tell you that notwithstanding repeated applications I find your Hogshead of Madeira (which is on its travels) may not arrive sooner than 4, 5, or 6 months. I must spare you all I can of my Old Madeira which is in London, but I do not know that it will amount to a quantity worth the trouble of sending. I shall make every effort and inquire everywhere for you. As to Sir Ralph Payne, surely a letter directed to him in London would find him, if you think that mode preferable.

Your plan as to Charlotte Porten might be the most desirable, but nothing could be more fancifull than to suppose it could possibly succeed, unless you could send a Demon cracked from Paris to hang the mother to a Lanthern.

My last letter answers your question whether Hester had left you the fee-simple of the Sussex Estate. I have learned nothing more concerning that Holy woman since the receipt of the Copy of her Will, nor am I likely, unless I should find some of the family of the Laws in London next winter. I think you should inclose to me an order to the Executors, Messrs. William Law, Senior, of Kings Cliffe, and William Law of Stamford, to deliver to me all the Writings, Papers, Surveys, Plans, &c., relating to the Sussex Estate, and you may add, those which relate to the Family of Gibbon.

When Batt was here not long since, I mentioned to him your old Aunt's Bequest and my proposition to you; at first, he did not object, but next day he scouted my folly and extravagance in diminishing my Income. My observations that I should and could easily cut down annually more timber than would pay the difference, and that in case I went to glory, those who came after me would be fully compensated in the end for loss of Income – I say, these observations seemed to make little impression on him. However, I was somewhat chilled, yet I cannot help thinking it or something of the kind might answer to both of us, if you should be desperately disposed to sell to increase your Income. I should acquire a position on the Sea-Shore – but you may have thought of something that would answer your purpose better.

You admire the Minister's secrecy and vigour. There is no secrecy in the case, but surely he has made a desperate plunge, and it appears to me a very wanton one – and if it is right to take an advantage, he is losing the opportunity.153 It is difficult to suppose that Spain will engage single-handed with us, but we may bully them into it, and although France cannot at present do much, yet the adherence of the National Assembly to the Family compact may help the Spaniards to be stout, and above all it would be good policy in the French Aristocrats to dash France into a war at all events.

You are incorrigible, but we desire that you will encourage De Severy to write. It is surprising he can write and remember English so well. The alterations in your Chateau pleased us very much. I have enquired more than once whether you would have the provision for Mrs. Gibbon to be £200 or £300. You pay the latter, but I understand.

Everybody is looking into Bruce's Travels.154 Part takes the attention, but they are abominably abused. Banks objects to the Botany, Reynell to the Geography, Cambridge to the History, The Greeks to the Greek, &c., &c.; yet the work is to be found on every table. Bruce printed the work, and sold 2000 copies to Robertson for £6000. He sells to the booksellers at 4 guineas, and they to their customers at 5 guineas.

555

M. LANGER AT WOLFENBUTTEL.

This letter is apparently written to M. Langer, the Librarian of the Ducal Library of Wolfenbuttel. A translation of part of it was found with Gibbon's manuscript of the Antiquities of the House of Brunswick, and published by Lord Sheffield (Gibbon's Miscellaneous Works, vol. iii. pp. 353-558).

À Rolle, ce 12 Octobre, 1790.Je vous aurois plutot remercié, Monsieur, des soins obligeans que vous avez bien voulû vous donner pour me procurer les Origines Guelficæ,155 si d'un côté notre honnête libraire Mr. Pott ne m'avoit pas appris que vous etiez en voyage, si de l'autre je n'avois pas été moi même en proye à l'acces de goutte le plus rigoureux et le plus long que j'aye encore éprouvé.

Nous revoici à present dans notre état ordinaire, je marche, et vous ne courez plus. Je vous suppose bien etabli, bien enfoncé dans votre immense bibliotheque dans un endroit qui fournit peut-être un choix plus étendu et plus interessant des morts que des vivans. Comme vous êtes également propre à vivre avec les uns et les autres, je desirerois pour votre bonheur aussi bien que pour celui de vos amis, que vous pûssiez enfin executer comme moi le projet de chercher une douce retraite sur les bords du lac Leman. Il s'en faut de beaucoup que vous n'y soyez oublié: nous parlons souvent de vous surtout dans la famille de Severy, nous regrettons votre absence et en nous rappellant l'aimable franchise, la vivacité piquante de l'Esclave, nous cherisons l'esperance de vous revoir parmi nous en homme libre, ne dependant que de vos gouts et pouvant vous donner tout entier aux lettres et à la societé.

Vous aurez sans doute appris la perte irreparable que j'ai faite du pauvre Deyverdun. En vertu de son testament et de mes arrangemens avec son heritier Mr. le Major de Montagny, je me suis assuré ma vie durant la jouissance de sa maison et de son jardin. Vous en connoissez tous les agrémens qui se sont encore augmentés par une dépense assez considerable et assez bien tendu que j'y ai faité depuis sa mort. Je dois être content de ma position mais on ne peut pas remplacer un ami de trente ans. Votre curiosité, peut-être votre amitié, desirera de connoitre mes amusemens, mes travaux, mes projets pendant les deux ans qui se sont écoulé depuis la dernière publication de mon grand ouvrage. Aux questions indiscretes qu'on se permet trop souvent vis-à-vis de moi, je responds avec une mine renfrognée et d'une manière vague, mais je ne veux rien avoir de caché pour vous et pour imiter la franchise que vous aimez, je vous avouerai naturellement que ma confidence est fondée en partie sur le besoin que j'aurai de votre secours.

Après mon retour d'Angleterre les premiers mois ont été consacrés à la jouissance de ma liberté et de ma bibliotheque, et vous ne serez pas étonné si j'ai renouvellé une connoissance familière avec vos auteurs Grecs et si j'ai fait vœu de leur reserver tous les jours une portion de mon loisir. Je passe sous silence ces tristes momens dans lesquels je n'ai été occupé qu'à soigner et à pleurer mon ami: mais dès que j'ai commencé à me retrouver un esprit moins agile, j'ai cherché à me donner quelque distraction plus forte et plus interessante que la simple lecture. Le souvenir de ma servitude de vingt ans m'a cependant effrayé et je me suis bien promis de ne plus m'embarquer dans une entreprise de longue haleine que je n'acheverois vraisemblablement jamais. Il vaut bien mieux, me suis je dit, choisir, dans tous les pays et dans tous les siecles, des morceaux historiques que je traiterai separément suivant leur nature et selon mon gout. Lorsque ces opuscules (je pourrai les nommer en Anglais, Historical Excursions) me fourniront un volume, je le donnerai au public: ce don pourroit etre renouvellé jusqu'a ce que nous soyons fatigués ou ce public ou moi même: mais chaque volume, complet par lui même, n'exigera point de suite, et au lieu d'être borné comme la diligence au grand chemin, je me promenerai librement dans le champ de l'histoire en m'arrêtant partout où je trouve des points de vue agreables. Dans ce projet je ne vois qu'un inconvenient, – un objet interessant s'étend et s'aggrandit sous le travail: je pourrois être entrainé au dela de mes bornes, mais je serai doucement entrainé sans prevoyance et sans contrainte.

THE HISTORY OF THE GUELFS.

Mes soupçons ont été vérifiés dans le choix de ma première excursion. Ce que j'avois si bien prevu n'a pas manqué d'arriver à mon premier choix et ce choix vous expliquera pourquoi j'ai demandé avec tant d'empressement les Origines Guelficæ. Dans mon histoire j'avois rendu compte de deux alliances illustres, d'un fils du Marquis Azo d'Este avec une fille de Robert Guiscard,156 d'une princesse de Brunswick avec l'Empereur Grec. Un premier appercu de l'antiquité et de la grandeur de la maison de Brunswick a excité ma curiosité, et j'ai cru me pouvoir interesser les deux nations que j'estime le plus par les mémoires d'une famille qui est sortie de l'une pour regner sur l'autre. Mes recherches, en me devoilant la beauté de ce sujet, m'en ont fait voir l'étendue et la difficulté. L'origine des Marquis de Ligurie et peut-être de Toscane a été suffisament eclaircie par Muratori et Leibnitz; l'Italie du moyen age, son histoire et ses monumens, me sont très connus et je ne suis pas mécontent de ce que j'ai déjà écrit sur la branche cadette d'Este qui est demeurée fidelle a garder ses cendres casanières. Les anciens Guelfs ne me sont point étrangers, et je me crois en etat de rendre compte de la puissance et de la chute de leurs heritiers, les Ducs de Bavière et de Saxe.

La succession de la maison de Brunswick au trône de la Grande Bretagne sera très assurément la partie la plus interessante de mon travail; mais tous les materiaux se trouvent dans ma langue, et un Anglois devroit rougir s'il n'avoit pas approfondi l'histoire moderne et la constitution actuelle de son pays. Mais entre le premier Duc et le premier Electeur de Brunswick il se trouve un intervalle de quatre cent cinquante ans, je suis condamné à suivre dans les tenèbres un sentier étroit et raboteux, et les divisions, les sous divisions, de tant de branches et de territoires repandent sur ce sentier la confusion d'un labyrinthe Genealogique. Les événemens sans éclat et sans liaison sont bornés à une province d'Allemagne et ce n'est que vers la fin de cette periode que je serois un peu ranimé par la reformation, la guerre de trente ans, et la nouvelle puissance de l'Electorat. Comme je me propose de crayonner des Memoires et non pas de composer une histoire, je marcherois sans doute d'un pas rapide, je presenterois des resultats plutot que des faits, des observations plutot que des récits: mais vous sentez, combien un tableau general exige de connoissances particulières, combien l'auteur doit être plus savant que son livre.

Or cet auteur, il est à deux cent lieues de la Saxe, il ignore la langue et il ne s'est jamais appliqué à l'histoire de l'Allemagne. Eloigné des sources, il ne lui reste qu'un seul moyen pour les faire couler dans sa bibliotheque. C'est de se menager sur les lieux même un correspondant exact, un guide eclairé, un oracle enfin qu'il puisse consulter dans tous ses besoins. Par votre caractère, votre esprit, vos lumières, votre position, vous êtes cet homme precieux et unique que je cherche, et quand vous m'indiquerez un suppléant aussi capable que vous même je ne m'addresserois pas avec la même confiance à un étranger. Je vous accablerois librement de questions, et de nouvelles questions naitroient souvent de vos reponses; je vous prierois de fouiller dans votre vaste depôt; je vous demanderois des notices, des livres, des extraits, des traductions, des renseignements sur tous les objets qui peuvent intéresser mon travail. Mais j'ignore si vous êtes disposé à sacrifier votre loisir, vos études chéries à une correspondance pénible sans agrémens et sans gloire. Je me flatte que vous feriez quelque chose pour moi, vous feriez encore davantage pour l'honneur de la maison à laquelle vous êtes attaché, mais suis-je en droit de supposer que mes ecrits puissent contribuer de quelque chose à son honneur?

J'attends, Monsieur, votre reponse qu'elle soit prompte et franche. Si vous daignez vous associer à mon entreprise, je vous envoyerai sur le champ mon premier interrogatoire. Votre refus me decideroit à renoncer à mon dessein, ou du moins à lui donner une nouvelle forme. J'ose en même tems vous demander un profond secret: un mot indiscret seroit repeté par cent bouches et j'aurois le desagrement de voir dans les journaux, et bientôt dans les papiers Anglois, une annonce, peut-être défigurée, de mes projets littéraires, qui ne sont confiés qu'à vous seul.

J'ai l'honneur d'être,E. G.556.

To Lord Sheffield

[Oct. 17, '90.]SERVITUDE TO LAWYERS.

You call me incorrigible: but I never was less disposed than at present to plead guilty. Have you forgot the general picture of mind, body and estate which I sent you since my recovery? in the tranquil life of Lausanne a long interval might elapse without affording any features to alter or any colours to vary. On the most interesting topic, poor Buriton, it is mine to hear rather than to write, and most ardently indeed do I now desire to hear of the conclusion of that incomprehensible business. Is it possible, are we under such servitude to the lawyers that an obsolete act without force or meaning should have hung us up for a year in Chancery? If I do not learn before the end of the year that the money is paid and placed, I shall be as miserable as pecuniary events can make me; when it is done I am easy and happy for life. In the midst of your arduous affairs I do not suspect any failure of zeal, but I now call upon you to redouble your speed, and to strain every nerve till we have reached the goal. Till the present business I never imagined that it was difficult to find people who would take your money. It is lucky that Sainsbury has consented to leave £8000 on Buriton: with regard to the remainder I leave it absolutely to your judgement, but since you distrust with reason private bond security, I see no other way than throwing it into the funds; a short delay might be allowed in expectation of their sinking, but the rise and fall are so uncertain, that it might be the 'rusticus expectat dum defluat amnis.' In the mean while Buriton rent must be paid, and as the two quarters due at Lady day had been neglected, the whole year till last Michaelmas must be rigorously exacted. I do not believe (though I would not give a gentleman the lye) that you ever asked me the question about Mrs. G.'s jointure: it will be an handsome, an easy compliment to give her a right to the three hundred which I pay her in fact.

Let us now make a tour to Newhaven. Upon the whole I am very well satisfied. You remark that about February, 1788, the old Saint decimated her nephew: but have you forgot that her atheistical nephew had neglected to accept her invitation and would not even write her a civil letter? surely he has no right to complain. I am ignorant of the character and behaviour of the Laws, but in the general principle of preferring friends to relations, I think her perfectly right. – You were not surely impatient for an answer to your proposal: it demands the coolest deliberation, and there cannot be the smallest occasion for dispatch. I will however impart such ideas as have arisen.

1. I agree with Batt in thinking it an unwise measure for yourself. Is this a time to diminish your income when you must enlarge or at least support your expence, when you know that for seven years to come you will not enjoy the benefit of a single winter fallow? If you have timber it will be sufficiently wanted for your annual supplies.

2. The balance of my fortune and my wishes depends on a contingency which I have neither power nor inclination to hasten. As soon as the Belvidere subsides, I am rich beyond all my plans of expence at Lausanne. Every winter such an event is probable, and it is highly probable that it will happen in three or four winters. It is indeed possible that a fine thread may be drawn to a great length without breaking, and if I turned a landed estate into an annuity, I should never be at a loss to employ the superfluity. If my heir, the creature of my choice does not think he has enough, the dog has too much.

557.

Lord Sheffield to Edward Gibbon

Sheffield Place, 3rd Jan., 1791.It occurs to me in the midst of much hurry, that you may have a wish for further information on the subject of the Madeira. It was shipped for Ostend on the 3rd Dec., with full and ample instructions (according to your own directions) for its conveyance to Basle, where it is to wait your further orders. I suppose that on the receipt of my former letter you wrote to your correspondent there.

The Wine is gone in one hogshead and one tierce, marked & No. E. G. No. 1 & 2.

The Bill as follows —

Probably it is the best wine of the kind that ever reached the centre of Europe. You will remember that an Hogshead is on his travels through the torrid zone for you. I suppose you do not mean to decline it when it arrives. No wine is meliorated to a greater degree by keeping than Madeira, and you latterly appeared so ravenous for it, that I must conceive you wish to have a stock.

I have had a Congress with Sainsbury, &c. The business has been referred to the Master of the Rolls. I have talked with the Master. It seems in good train. The conveyance is preparing. The message of young Porten is very troublesome. Sainsbury wished to avoid taking the £8000 on mortgage. I remonstrated strongly. He agreed, handsomely, to take it rather than embarrass. I have promised £4000 on a Yorkshire mortgage. I have been very busy in Town. I am glad I cannot finish the Paper, because you are such a worthless fellow, that you do not answer even on business.

Yours ever,S.N.B. – The Birth of Maria, & the Justices are waiting for me at the Inn.

558.

To Lord Sheffield

1791.GIBBON'S SERIOUS ILLNESS.

*Your indignation will melt into pity, when you hear that for several weeks past I have been again confined to my chamber and my chair. Yet I must hasten, generously hasten, to exculpate the Gout, my old enemy, from the curses which you already pour on his head. He is not the cause of this disorder, although the consequences have been somewhat similar.* After some days of fever and a most violent oppression in my head and stomach, the morbid humour forced itself into my right leg, which was covered from my knee to my toe with a strong inflammatory Erisipèle or Rash. I was gradually relieved by a plentiful discharge of pus atque Venenum (excuse the indelicacy) which, according to my Physician, has surpassed that of fifty blisters. The skin has been compleatly renewed, and I now crawl about the house upon two sticks. *I am satisfied that this effort of nature has saved me from a very dangerous, perhaps a fatal, crisis; and I listen to the flattering hope that it may tend to keep the Gout at a more respectful distance.* You will determine whether it ought to raise or sink the purchase of my annuity.

I must confess that I am disappointed, vexed, harrassed, fatigued with the strange procrastination of the Buriton affairs which are now verging to the end of the second year. In former transactions while we were fighting with knaves and madmen nothing could surprise, but in this amicable connection with a willing and able purchaser, it is indeed provoking that term after term we should be hung up (a most proper expression) in the forms of the Court of Chancery. You are now on the spot, and I conjure you by every tye of friendship and humanity to steal some moments from the service of Bristol, to strain every nerve of your active genius, and to send me a speedy and satisfactory account that the business is terminated, and the money paid. The funds are indeed so very high, that I agree with you in preferring a clear four per cent. which they do not yield, on the solid basis of the Earth, I mean on good landed security. I therefore much approve of your holding Sainsbury to his engagement of retaining the £8000 on the mortgage of Buriton's own self, and hope you will not fail of success in registering £4000 more in Yorkshire. Should any loose hundreds remain, they may be best added to my India bonds in Gosling's hands. I much fear that another half year from Buriton will become due (at Lady-day), and hope you will order Andrews to exact it without mercy or delay.

I feel myself much embarrassed how to define or establish my claims on Hugonin. We always treated with the confidence of friends, and the ease of Gentlemen, and his short accounts, from art or accident, were always so vague, that I could never discern to what half year his remittances applied. I am satisfied that two years or at least eighteen months have never been accounted for; but on the most moderate footing I may demand the year's rent which ended at Michaelmas 1788, and which was not paid when I left England. The agency of Hugonin will not be disputed, the Tenant's receipt will prove that it was paid into his hands, and even the silence of Gosling's books will afford some evidence that it never was remitted for my use. Besides, will not the onus probandi rest on Hugonin's heirs, who ought to produce my discharge? On recollection I may even state my damages at eighteen months, since according to a vile abuse, the tenant only paid at Michaelmas the year's rent which had been due the previous Lady-day.

ACCEPTS ANNUITY FOR NEWHAVEN.

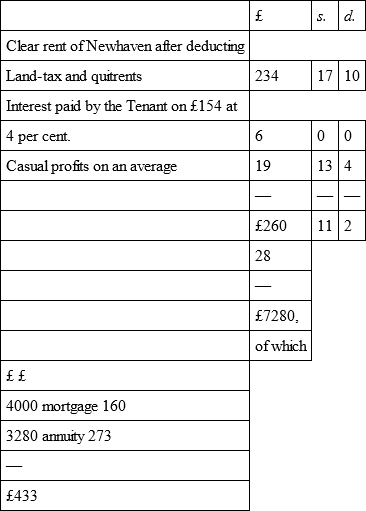

I now proceed to the important business of Newhaven, and am not sorry that we have both of us taken sufficient time to avoid the reproach of rash and precipitate measures. As you are not an infant I will decline any farther remonstrance of what may be proper or improper for yourself, and will think solely of my own interest. After mature consideration I am resolved to amplify my income by the sale of Newhaven, leaving one half of the purchase money to sink in an Annuity and the other half to swim in a Mortgage. My old scruples against pecuniary transactions with a friend are much diminished by my experience of the delays and difficulties which occur in a treaty with a stranger, and I flatter myself that you will not think it necessary to ascertain my title to the Estate by an amicable suit in Chancery. Your statement is impartial and your terms are liberal: Twenty-eight years' purchase appears a fair price for an Estate circumstanced like mine, and I am not ambitious of paying more than twelve years for the chance of my earthly existence. But I do not perfectly acquiesce in your striking off the casual profits to balance the casual losses and repairs, and I must request that you would try a very simple calculation: Supposing the three per Cents at eighty, your landed estate, after deducting every possible outgoing, would pay you as good interest as your money in the funds. Is such an equality reasonable? Should you pay nothing for the solid security of land? Is the National Debt less exposed than the Sussex acres to be swallowed in the Ocean? The calculation is easy.

Suppose we reduce this sum to £7000 and divide it equally, the produce will be £430 (£140 for the Mortgage, £290 for the Annuity). I cannot think my expectations quite unreasonable, but I leave the final arbitration to yourself, as if we were treating with a third person, and I authorize you to conclude with Lord Sheffield on such conditions as I ought to ask and he will be disposed to give. The farm itself will never answer for the Mortgage, and you will obtain a good and sufficient security for the annuity. In the meanwhile I should be glad to know when I may expect the payment of some rent, and from what date it will begin to accrue to me.

N.B. – Your own offer is £4200, the Mortgage; £280 Annuity. But arithmetic is erroneous: 3052 divided by 12 do not produce 280 but only 254. You are a pretty man of business. So much for Newhaven.

Since we are talking of Wills, I must request that you would commit mine to the flames. By the first opportunity I will send you the duplicate of another which I have constructed on more rational principles. You will not disapprove the preference which I now give to the children of Sir Stanier Porten: they are the nearest, the most indigent and the most deserving of my relations.