Полная версия

Полная версияWhip and Spur

In this storied little island one is never for long out of the presence of places on the traditions of which our life-long fancies have been fed. Our road home lay past the indistinct mass of rubbish, clustered round with ivy and with the saddest associations, which was once Fotheringay Castle; and as we turned into the village my companions pointed out the still serviceable but long-unused “stocks” where the minor malefactors of the olden time expiated their offences.

We reached the Haycock at three, a moist but far from unpleasant body of tired and dirty men, having ridden, since nine in the morning, over fifty-five miles, mostly in the rain, and often in a shower of mud splashed by galloping hoofs. By six o’clock we were in good trim for dinner, and after dinner for a long, cosey talk over the events of the day, and horses and fox-hunting in general. My own interest in the sport is confined mainly to its equestrian side, and I am not able to give much information as to its details. Any stranger must be impressed with the firm hold it has on the affections of the people, and with the little public sympathy that is shown for the rare attempts that are made to restrict its rights.

It would seem natural that the farmers should be its bitter opponents. It can hardly be a cheerful sight, in March, for a thrifty man to see a crowd of mad horsemen tearing through his twenty acres of well-wintered wheat, filling the air with a spray of soil and uprooted plants. But let a non-riding reformer get up after the annual dinner of the local Agricultural Association and suggest that the rights of tenant-farmers have long enough lain at the mercy of their landlord and his fox-hunting friends, with the rabble of idle sports and ruthless ne’er-do-weels who follow at their heels, and that it is time for them to assert themselves and try to secure the prohibition of a costly pastime, which leads to no good practical result, and the burdens of which fall so heavily on the producing classes,—and then see how his brother farmers will second his efforts. The very man whose wheat was apparently ruined will tell him that in March one would have said the whole crop was destroyed, but that the stirring up seemed to do it good, for he had never before seen such an even stand on that field. Another will argue that while hunting does give him some extra work in the repair of hedges and gates, and while he sometimes has his fields torn up more than he likes, yet the hounds are the best neighbors he has; they bring a good market for hay and oats, and, for his part, he likes to get a day with them himself now and then. Another raises a young horse when he can, and if he turns out a clever fencer, he gets a much larger price for him than he could if there were no hunting in the country. Another has now and then lost poultry by the depredations of foxes, but he never knew the master to refuse a fair claim for damages; for his part, he would scorn to ask compensation; he likes to see the noble sport, which is the glory of England, flourishing, in spite of modern improvements. At this point, and at this stage of the convivial cheer, they bring in the charge at Balaklava, and other evidences that the noble sport, which is the glory of old England, breeds a race of men whose invincible daring always has won and always shall win her honor in the field;—and Long live the Queen, and Here’s a health to the Handley Cross Hunt, and Confusion to the mean and niggardly spirit that is filling the country with wire fences and that would do away with the noble sport which is the glory of old England! Hear! hear!! And so it ends, and half the company, in velvet caps, scarlet coats, leathers and top-boots, will be early on the ground at the first meet of the next autumn, glad to see their old cover-side friends once more, and hoping for a jolly winter of such healthful amusements and pleasant intercourse as shall put into their heads and their hearts and into their hearty frames and ruddy faces a tenfold compensation for the trifling loss they may sustain in the way of broken gates and trampled fields.

I saw too little to be able to form a fair opinion as to the harm done; but when once the run commences no more account is made of wheat, which is carefully avoided when going at a slow pace, than if it were so much sawdust; fences are torn down, and there is no time to replace them; if gates are locked, they are taken off the hinges or broken; if sheep join the crowd in an enclosure and follow them into the road, no one stops to see that they are returned: we are after the hounds, and sheep must take care of themselves. I saw one farmer, in an excited manner, open the gates of his kitchen-garden and turn the hounds and twenty horsemen through it as the shortest way to where he had seen the fox go; his womenfolk eagerly calling “Tally-ho!” to others who were going wrong. I have never seen a railroad train stopped because of the conductor’s interest in a passing hunt, but I fancy that is the only thing in England that does not stop when the all-absorbing interest is once awakened.

Whatever may be the effect on material interests, the benefit of this eager, vigorous, outdoor life on the health and morals of the people is most unmistakable. Such a race of handsome, hale, straight-limbed, honest, and simple-hearted men can nowhere else be found as in the wide class that passes as much of every winter as is possible in regular fox-hunting; and to make an application of their example, we could well afford to give over many of our fertile fields to ruthless destruction, and many of our fertile hours to the most senseless sport, if it would only replace our dyspeptic stomachs, sallow cheeks, stooping shoulders, and restless eagerness with the hale and hearty and easy-going life and energy of our English cousins. Hardly enough women hunt in England to constitute an example; but those who do are such models of health and freshness as to make one wish that more women had the benefit of such amusement both there and here. It is very common to see men of over sixty following the hounds in the very élite of the field; they seem still in the vigor of youth. At seventy many are yet regular at their work; and it is hardly remarkable when one finally hangs up his red coat only at the age of eighty. Considering all this, it almost becomes a question whether, patriotism to the contrary notwithstanding, it would not be a good thing for a prosperous American, instead of settling down at the age of forty-five to a special partnership and a painful digestion, to take a smaller income where it would bring more comfort, and by a judicious application of the pig-skin to rehabilitate his enfeebled alimentation.

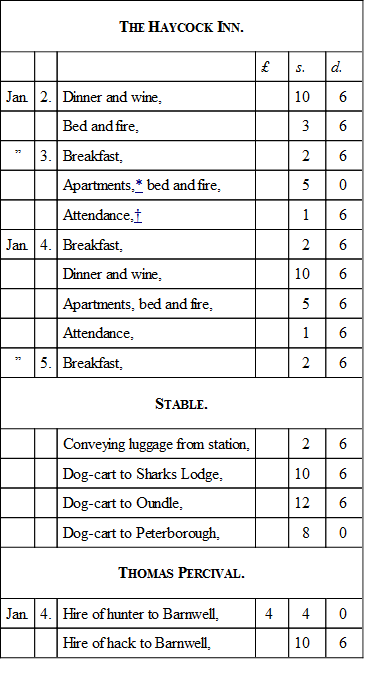

Fox-hunting is a costly luxury if one goes well mounted and well appointed. It can hardly be made cheap, even when one lives in his own house and rides his own horses. With hotel bills and horse-hire, it costs still more. As an occasional indulgence it is always a good investment. My own score at the Haycock was as follows,—by way of illustration, and because actual figures are worth more than estimates. (I was there from Thursday afternoon until Sunday morning, went out with a shooting-party on Friday, dined out on Friday night, and hunted on Saturday.)

* The run of the house.

† We are apt to consider this a petty swindle, but it has the advantage that you get what you pay for.

Eight pounds, twelve shillings, and sixpence; which being interpreted means $47.30 in the lawful currency of the United States. The hunter and hack for one day cost $23.52.

An American friend living with his family in Leamington (much more cheaply than he could live at home), kept two hunters and a hack, and hunted them twice a week for the whole season (nearly six months) at a cost, including the loss on his horses, which he sold in the spring, of less than $1,500. I think this is below the average expense.

The cost of keeping up a pack of hounds is very heavy. The hounds themselves, a well-paid huntsman, two or three whippers-in, two horses a day for each of these attendants (hunting four days a week, this would probably require four horses for each man), and no end of incidental expenses, bring the cost to fully $20,000 per annum. This is sometimes paid wholly or in part by subscription and sometimes entirely by the Master of the Hounds. One item of my friend’s expenses at Leamington was a subscription of ten guineas each to the Warwickshire, North Warwickshire, Atherstone, and Pytchley hunts. Something of this sort would be necessary if one hunted for any considerable time with any subscription pack, but an occasional visitor is not expected to contribute.

A stranger participating in the sport need only be guided by common modesty and common-sense. However good a horseman he may be, he cannot make a sensation among the old stagers of the hunting-field. Probably he will get no commendation of any sort. If he does, it will be for keeping out of the way of others,—taking always the easiest and safest road that will bring him well up with the hounds, not flinching when a desperate leap must be taken, and following (at a respectful distance) a good leader, rather than trying to take the lead himself. However promising the prospect may be, he had better not do anything on his own hook; if he makes a conspicuous mistake, he will probably be corrected for it in plainer English than it is pleasant to hear.

One of the memorable days of my life was the day before New-Year’s. Ford had secured me a capital hunter, a well-clipped gelding, over sixteen hands high, glossy, lean, and wiry as a racer. “You’ve got a rare mount to-day, sir,” said the groom as he held him for me to get up; and a rare dismount I came near having in the little measure of capacity with which Master Dick and I commenced our acquaintance, before we left the Regent. He was one of those horses whose spirits are just a little too much for their skins, and all the way out he kept up a restless questioning of his prospect of having his own way. Still he was in all this, as in his manner of doing his work when he got into the open country, such a perfect counterpart of old Max, who had carried me for two years in the Southwest, that I was at home at once. If I had had a hunter made to order, I could not have been more perfectly suited.

The meet (North Warwickshire) was at Cubbington Gate, only two miles from Leamington, and a very gay meet it was. The road was filled with carriages, and there was a goodly rabble on foot. About three hundred, in every variety of dress, were mounted for the hunt, a dozen or so of ladies among them. Three of these kept well up all day, and one of them rode very straight. The hounds were taken to a wood about a mile to the eastward of Cubbington, where they soon found a fox, which led us a very straight course to Princethorpe, about three miles to the northeast.

I had done little fencing for seven or eight years, and the sort of propulsion one gets in being carried over a hedge is sufficiently different from the ordinary impulses of civil life to suggest at first the element of surprise. Consequently, though our initial leap was a modest one, I landed with only one foot in the stirrup and with one hand in the mane; but I now saw that Dick was but another name for Max, and this one moderate failure was enough to recall the old tricks of the craft. As the opportunity would perhaps never come again, this one was not to be neglected, and I resolved to have one fair inside view of real fox-hunting. Dick was clearly as good a horse as was out that day; the leaping was less than that to which we were used among the worm-fences, fallen timber, and gullies of Arkansas and Tennessee; and there was but a plain Anglo-Saxon name for the only motive that could deter me from making the most of the occasion. Mr. Lant, the Master of the Hounds, was not better mounted for his lighter weight than was I for my fourteen stone; and his position as well as his look indicated that he would probably go by the nearest practicable route to where the fox might lead, so we kept at a safe distance behind him and well in his wake. The hesitation and uncertainty which had at first confused my bridle-hand being removed, my horse, recognizing the changed position of affairs, settled down to his work like a well-trained and sensible but eager beast as he was. From the covert to Princethorpe we took seven fences and some small ditches, and we got there with the first half-dozen of the field, both of us in higher spirits than horse and rider ever get except by dint of hard going and successful fencing.

Here there was a short check, but the fox was soon routed out again and made for Waveley Wood, a couple of miles to the northwest.

Waveley Wood is what is called in England a “biggish bit of timber,” and the check here was long enough to allow the whole field to come up. As we sat chatting and lighting our cigars, “Tally-ho!” was called from the other side of the cover, and we splashed through a muddy cart-road and out into the open just as the hounds were well away. Now was a ride for dear life. Every one had on all the speed the heavy ground would allow. In front of us was a “bullfinch” (a neglected hedge, out of which strong thorny shoots of several years’ growth have run up ten or twelve feet above it). I had often heard of bullfinches, and no hunting experience could be complete without taking one. It was some distance around by the gate, the pace was strong, and the spiny fringe had just closed behind Mr. Lant’s red coat as he dropped into the field beyond. “Follow my leader” is a game that must be boldly played; so, settling my hat well down, holding my bridle-hand low, and covering my closed eyes with my right elbow, with the whip-hand over the left shoulder, I put my heart in my pocket and went at it, and through it with a crash! An ugly scratch on the fleshy part of the right hand was the only damage done, and I was one of the very few near the pack. Dick and I were now up to anything; we made very light of a thick tall hedge that came next in order, and we cleared it like a bird; but we landed in a pool of standing water, covering deeply ploughed ground, the horse’s forefeet sinking so deeply that he could not get them out in time, and our headway rolled us both over in the mud, I flat on my back. Dick got up just in time for his pastern to strike me in the face as I was rising, giving me a cut lip, a mouthful of blood, and a black and blue nose-bridge. My appearance has, on occasions, been more respectable and my temper more serene than as I ran, soiled and bleeding, over the ploughed ground, calling to some workmen to “catch my horse.”

I was soon up and away again. There seemed some confusion in the run, and the master being out of sight, I followed one of the whips as he struck into a blind path in a wood. It was a tangled mass of briers, but he went in at full pace, and evidently there was no time to be lost. At the other side of the copse there was a set of low bars, and beyond this a small, slimy ditch. My leader cleared the bars, but his horse’s hind feet slipped on the bank of the ditch, and he fell backwards with an ugly kind of sprawl that I had no time to examine, for Dick took the leap easily and soon brought me into a field where, on a little hillock, and quite alone, stood the huntsman, dismounted, holding the dead fox high in his left hand, while with his long-leashed hunting-crop he kept the hungry and howling pack at bay. The master soon came up, as did about a dozen others, including a bright little boy on a light little pony. The fox’s head (mask), tail (brush), and feet (pads) were now cut off and distributed as trophies under the master’s direction. The carcass was then thrown to the pack, that fought and snarled over it until, in a twinkling, the last morsel had disappeared. This was the “death,”—by no means the most engaging part of the amusement. From the find to the killing was only twenty-five minutes, into which had been crowded more excitement and more physical happiness than I had known for many a long day.

The second cover drawn was not far away. With this fox we had two hours’ work, mainly through woods at a walk and with the hounds frequently at fault, but with some good leaping. Finally he was run to earth and abandoned.

We then went to a cover near Bubbenhall, but found no fox, and then, with the same luck, to another east of Baggington. It was now nearly four o’clock, growing dusk, and beginning to rain. The hounds started for their kennels, and Dick and I took a soft bridle-path skirting the charming road that leads, under such ivy-clad tree-trunks and between such hedges as no other land can show, through Stoneleigh Village and past Stoneleigh Abbey to Leamington, and a well-earned rest.

My memorandum for that day closes: “Horse, £2 12s. 6d.; Fees, 2s.; and well worth the money.”

THE END