Полная версия:

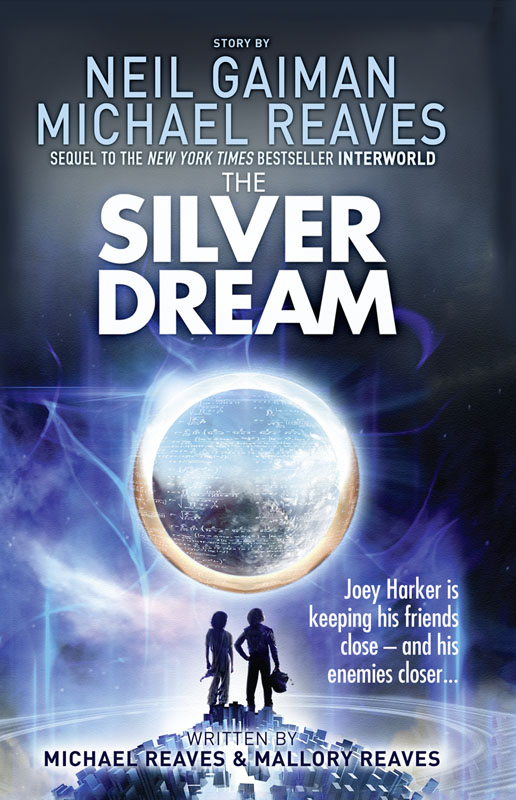

The Silver Dream

Dedication

For MALLORY

with deep appreciation

from Michael and Neil

For KARI

and the MARKER-MORSE FAMILY

from Mallory

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

CHARACTER GUIDE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ALSO IN THIS SERIES

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Joey’s Team

Joey Harker

J/O HrKr—male, younger cyborg version of Joey.

Jai—male, senior officer. Spiritual, likes big words.

Jakon Haarkanen—female, wolflike.

Jo—female, has white wings, can fly only on magic worlds.

Josef—male, comes from a denser planet. Large and strong.

Other Walkers of Note

Jaya—female, red-gold hair, voice like a siren.

Jenoh—female, catlike. Mischievous.

Jerzy Harhkar—male, quick and birdlike, feathers for hair. Joey’s first friend on Base.

Joaquim—male, new Walker.

Joliette—female, vampirelike. Has a friendly rivalry with Jo.

Jorensen—male, senior officer. Good-natured, taciturn.

Teachers and Officers

Jaroux—male, the librarian. Loves knowledge, is friendly and quirky.

Jayarre—male, Culture and Improvisation teacher. Cheerful, charismatic.

J’emi—female, Basic Languages teacher.

Jernan—male, quartermaster. Strict and stingy with equipment.

Jirathe—female, Alchemy teacher. Body made from ectoplasm.

Joeb—male, team leader, senior officer. Laid-back, brotherly attitude.

Jonha—male, officer. From a magic world. Skin like tree bark.

Jorisine—female, officer. From a magic world. Elflike.

Joseph Harker (the Old Man)—male, the leader of InterWorld. Older version of Joey. Stern, has a cybernetic eye.

Josetta—female. The Old Man’s assistant. Friendly, well organized, no-nonsense.

Josy—female, officer, has long golden hair with knives braided into it.

CALL ME JOE.

Please.

It’s not that I have anything against “Joey”—it’s a perfectly good name, and it’s worked fine for the first sixteen years of my life. But that’s the point. I’m sixteen now, almost seventeen, and the name “Joey” just doesn’t feel like me anymore. Which maybe isn’t surprising, given that I’ve met more versions of myself than Star Wars has clones. When you stop to think about it, I’ve probably got the biggest identity crisis of all time going, so if I want to drop one lousy letter from my name, I think I’m entitled.

I was trying to explain this to Jai, which wasn’t easy, considering that we and the rest of the team were pinned down by Binary scouts shooting what looked like elongated blobs of mercury at us, and Jai’s not the easiest person to talk to unless you happen to have a dictionary chip installed between your ears. Which I don’t.

He listened, returning fire with more mercury blobs (which are called “plasma pods” in case you’re wondering), and then asked, “Are you unambiguously certain?” Behind him, Jakon leaped on top of a power condenser, crouching all sleek and furry, snarling as she looked for more prey. The wolf girl version of me looked like she might be enjoying this a little. She always did, but I suppose there was nothing wrong with loving your job. . . .

“Excuse me,” Jai said crisply, aiming over my shoulder down the length of the big chamber in the abandoned power plant. He fired the emitter, which made a sort of thwip! sound. I caught a crazy, distorted glimpse of movement from behind me, reflected off the chest area of Jai’s encounter suit: a Binary scout on a grav-board, trying for a sneak attack. Then the plasma pod hit him and negated the binding force in his atomic nuclei, which is how Jai would’ve described it. Me, I’d just say he disappeared in a puff of smoke and a sound like zzzapht!!

This caused a momentary lull in the fighting on both sides, which I took advantage of to ask what he meant. “Huh?” I said. (I get a lot more mileage out of words than Jai does.)

“Are you unambiguously certain?” he repeated patiently. He pointed the emitter in various directions. Thwip. Thwip.

Next to me, J/O fired his laser-cannon arm at a group of attacking scouts. “That means are you sure,” he offered helpfully, and I rolled my eyes. J/O did have a dictionary chip installed between his ears, and took every opportunity to make me aware of it. I ignored him.

“That I want to change my nickname? Yes.”

“No, that your chronological age is in fact sixteen.”

I started to tell him that his brain had finally grown too big for his head, but stopped. He had a point.

Though we don’t time travel in the classic sense in the InterWorld organization, we all know that time itself isn’t independent, aloof, and serene from all the myriad worlds that make up the various versions of Earth. Though I’d never encountered any Earths on which time itself seemed subjectively altered—Earths on which everyone seemed to ta-a-a-l-lk-k . . . r-e-e-a-l . . . s-l-o-o-w . . . or Earths where everyoneranaroundliketheywereinanoldsilentmovieandtheyalltalkedlikethis!—still, most people knew that time passed quicker or slower in some planes as opposed to others. Just as it was also known that after some time spent in those worlds, your own time sense, not to mention your body, adjusted to the new temporal reality.

I’d been in quite a few such parallel planes in the time I’d been a member of InterWorld. Which meant that Jai had a valid reason for asking, but only up to a point. I might be, as far as I knew, older than my birthday said I was. Or younger. Problem was, there was no way to measure the rate that time passed “outside” the plane we were in. And even if there were, what about time spent in the In-Between, that crazy-quilt collision of various realities and worlds that a Walker used as a shortcut from one reality to the next? Besides, it was all subjective, tied in with consciousness, so really, you only were “as old as you felt.”

I said as much to Jai, who looked at me as if I’d just pointed out to him that the sky was blue. (Usually. On this world it was more greenish.) “Indubitably,” he said, and then he lost me again. “And are you unquestionably certain your haecceity is defined by your moniker?”

“My what?”

“Your moniker. Your name.”

“I know that one. My . . . hi-ex-it . . . ?”

“Haecceity. Your youness. The qualities that make you you, rather than me.”

“Even I didn’t know that one,” J/O admitted, looking like he was filing it away somewhere—which he likely was.

“That’s an ironic thing to ask,” I said, “considering that you are me. Or I’m you, whichever.”

“Yet we all possess qualities which render us unique. Haecceity is the particular characteristics of those qualities that make you you.”

Thwip. Thwip. Zzzapht!!

I pondered that as another rutabaga bit the dust. I was getting used to seeing it, which was both a relief and a disturbance, if you know what I mean. The emitter dissolved the atomic bonding, which meant no muss, no fuss. They just went poof—or zzapht. And they weren’t people in the same sense that we were. They looked human until you got up close; then their skin had a waxy, unfinished look, which made sense, since they were actually clones made primarily from cellulose and plant matter. The Binary was big on cookie-cutter assembly-line cannon fodder, just like HEX’s armies of choice were usually zombies. There wasn’t much point in feeling bad about killing something that was nine-tenths dead to begin with. But it still bothered me that it was bothering me less, if that makes any sense.

I was about to say something else to Jai, when I heard Josef approaching. Josef came from a world much denser than most of ours, so it wasn’t hard to recognize his heavy tread. “What’s up, Josef?” I asked, without turning my head. I was tracking another rutabaga.

He didn’t reply immediately, so I squeezed off my shot (thwip!) and glanced over my shoulder at him. “They’ve sent in reinforcements,” he rumbled, looking troubled.

“How many?” Jai asked, and I knew then it was bad, because Jai usually can’t ask anything in less than ten syllables. Josef shook his head.

“Too many to count quickly.”

J/O turned and looked at the nearest blank wall. “Tapping into an exterior security cam,” he said. J/O’s a cyborg version of me, from an Earth that is currently recovering from the Machine Wars. He’s got more hydraulic fluid circulating in him than blood, so when I watched the color drain from his face I knew something was very wrong. He was younger than me by a few years, and while he always handled himself well on missions—and made sure to point it out when he did—it was moments like this that I was reminded of his youth.

“Let’s see,” I said.

One of his eyes was cybernetic; it usually looked almost identical to his natural eye, save the circuitry going through it. That eye grew brighter, and on the wall there appeared a black-and-white projection of the outside. At first there was little to see: just more blasted masonry, exposed rebar, and the like. But then—

There was movement.

Lots of movement.

Rutabagas swarmed down the blasted, torn-up streets; over, around, and through walls; and even up from manholes and huge cracks in the pavement. There must’ve been a hundred in the first couple of minutes. And they just kept coming.

J/O had only tapped into the visual, not the audio, if there even was one. It really was eerie, seeing them coming, wave after wave, in utter silence.

And I realized that the silence also meant the hostilities had stopped inside the power plant. The veggie clones already in here with us had ceased their attack. Of course: No point in wasting more of their numbers when they can just sit back and wait. Six of us against five hundred or so of them . . .

Suddenly my deep and abiding concern over what I wanted to be called didn’t seem very important.

The walls and floor began to tremble. They were right outside.

“What now, fearless leader?” This was from Jo, another version of me—a girl with angelic white wings.

“Now I think we die,” Josef rumbled. Big guys are usually phlegmatic, and they didn’t get much bigger than Josef.

I gripped my emitter hard. “Not on my watch,” I said.

Jakon looked at me. Her eyes glittered in her furry face. “And what are you gonna do?”

“Think of something,” I said, with far more confidence than I felt.

A shot fired by a rutabaga outside demolished the camera J/O was tapped into. The feed dissolved in a burst of static. At the far end of the big chamber I could see what remained of the initial Binary attack force gathering. Behind us a window shattered, and rutabagas began climbing in.

I looked around wildly. Left, right, down, up—there was an air vent above us, the kind that might have led to vent shafts, but I wasn’t sure how much help that would be. Certainly Josef couldn’t fit up there; he was almost twice my size and about four times as dense. Jo had her wings, but she couldn’t do more than glide unless there was enough magic in the air to support flight; this world was completely taken over by Binary, much closer to the technological end of the spectrum than the magical—and she couldn’t carry more than one of us anyway.

I raised my arm to give the order to attack. There was no time left and no other choice. I couldn’t sense a portal anywhere near us, so we couldn’t escape through the In-Between. If Hue had come along on this assignment, things might’ve been different, but the little pan-dimensional critter’s a lot like a cat: Sometimes he just disappears for weeks at a time.

We needed a miracle, but I wasn’t going to put a lot of faith in the term “deus ex machina” when we were surrounded by Binary.

We’d have to fight. Before I could give the order, however, the air in front of us began to glow. It was warm, the kind of cozy heat that radiated from a fireplace on a cold night. The glow formed an oval shape, and through it stepped a girl.

My age, no more—if that. She had shaggy black hair and wore a strange outfit that seemed cobbled together out of various locales and times: Moorish pantaloons, a mantle from the Renaissance, a blouse that looked Victorian. I noticed all those later, though. At the moment all I noticed were her hands.

Actually her fingernails, to be exact. Each nail looked like a tiny circuit board. She pointed her right index finger at the Binary scouts. The nail glowed green, the rutabagas were surrounded by a green light, and . . . froze. Not in terms of temperature but in terms of movement. Then she pointed her left pinkie at us; it glowed, and we were all enveloped in a purple light.

Just before the room disappeared, she looked at me. I had a brief impression of long lashes surrounding violet eyes. “Hey, cutie,” she said. And winked.

I saw Jakon give me a big grin, full of fangs. And I knew, as the chamber vanished from around us, that I’d turned crimson clear to the tips of my ears.

THE IRONY IS THAT I’ve been known to get lost just going from my bunk to the bathroom.

I used to think it was simply that I had no sense of direction. And it’s true—I didn’t. But one thing I’ve learned over the last two years is that things are never simple. It turns out that my lousy sense of direction is limited to the first three spatial dimensions: longitude, latitude, and altitude. But there are other directions, lots of them. Eight at least, and probably a whole bunch more.

If you’re like I was at first, just trying to visualize eight or more ways that proceed at right angles on top of the three we already have gives you a massive ice cream headache. Where are these other dimensions? Why can’t we interact with them the way we do with the three we already have?

Well, according to the brain trust at Base Town, they were “compactified” (one of the fun things about being a scientist is being able to make up new words) the instant this universe began; somehow they were shrunk down to distances less than the diameter of an atom. If you pick any one of the “big three”—let’s say “up”—you can use it as an infinite vector and head away from the Earth—past the moon, past Mars . . . out of the solar system and into the dark. You’ll never run out of “up.”

That’s because we live—most of us, anyway—in a three-space world (or four, if you want to get technical). In a three-space world there’s just enough room for three vectors to proceed at ninety degrees from a point; they’re mutually perpendicular. (Time is a constant until we get fairly far up the asymptotic curve, so we can ignore it for now.) But there are also universes where the rules are “looser,” where there’s more “room” for new directions to exist.

I know—it’s hard to conceive of such things. But remember: All we really know of the universe is what filters in through our senses, and that isn’t a whole lot. Take the electromagnetic spectrum. It includes virtually every ripple of energy that powers the cosmos, from the long, lazy radio waves we communicate with through microwaves that we cook with all the way up to X-rays and gamma rays, which pack enough punch into their wavelengths to outshine an entire galaxy. All that majesty, all that infinite variety of energy, and all we see is a narrow little slice of it: seven measly colors. It’s like being invited to a royal banquet and then only being allowed to pick the crumbs off one plate.

So, take everything I just told you, and then try to imagine it all at once. Things moving at angles you didn’t even know existed, inverting and reverting and transforming, all painted with colors and textures and noises, and mash it all together. Then picture it reflected in two cracked mirrors, facing each other. That’s kind of what the In-Between is like.

That’s where the girl took us, though it was by far the most wrenching transition I’d ever experienced. I’d traveled to the In-Between more times than I could count by now, and the jump had never once made me feel as queasy as it did when she brought us there.

That’s where we were, though; I could tell before I even opened my eyes. All my senses, both internal and external, were verifying it. I could tell by the incredible and ever-changing sounds: mostly wind chimes but occasionally faraway noises like car horns, rumblings, birdsongs, water flowing, and every now and then the strains of an old instrumental from the 1930s that my dad was fond of, “Powerhouse,” by Raymond Scott. If you’ve ever watched an old Warner Bros. Looney Tunes cartoon, you’ve probably heard it. I could smell paprika; chocolate; and an astringent, medicinal smell that I couldn’t identify. The breeze felt now like feathers, now like fine-grain sandpaper. All this before I even opened my eyes.

So I opened my eyes.

I was standing on what looked like a Rand McNally globe of a terrestrial planet. It was maybe twenty feet in diameter and I was sticking out from it at a forty-five-degree angle, halfway between the equator and the South Pole, just like the Little Prince on his asteroid (assuming the South Pole was on the “bottom” relative to me and the rest of my team, who were standing or floating upon or nearby a whole slew of various other improbabilities).

And something wasn’t right.

That probably seems like a pretty ridiculous statement; after all, when is anything ever right about the In-Between? It’s the essence of wrongness, entropy’s landfill. Saying there was something not right about it was like saying there was something a little scary about Lord Dogknife.

But the feeling was unmistakable. Furthermore, it wasn’t going away.

Jo opened her eyes then, and by the look on her face, I could tell she felt the same way.

J/O looked accusingly at me. “Where did you take us?”

“Hey, I didn’t take us anywhere! It was that girl,” I said. Technically, Jai was our senior officer, but after a training mission had gone awry and I’d rescued them from the clutches of HEX, most of them tended to look to me in a pinch. There are drawbacks to being even an unofficial team leader, the biggest of which is getting blamed for everything.

“Fine, then where’d your girlfriend take us?” Jo’s voice was as accusing as J/O’s glare, and it probably didn’t help my case that I was crimson again, but I tried to protest anyway. “She’s not my—”

Before I could finish, several members of my team gave little reactions of surprise, looking past me. I whirled as the unfamiliar voice sounded from behind me, my hands coming up in a defensive position. I know it sounds like cheesy kung fu movie stuff, but you learn to think fast in the In-Between.

“Yes, I’d say that is rather premature,” said the mysterious girl, giving me another wink, “since we’ve only just met.”

“Who are you?” The question was clear and strong, the voice of someone not at all intimidated—unfortunately, it was Jakon’s voice, not mine. All I’d managed to do was stutter. My tongue felt like it was tied in a Gordian knot.

“A friend,” she answered easily, giving a little shrug of one shoulder. When I’d still been home—before my life became cluttered with Multiverses, Altiverses, and versions of me sporting fur, fangs, wings, and bionic implants—I had a wild, passionate, undying crush on a girl named Rowena. Rowena had sometimes done that artless little shrug when she was being silly or coy. I’d come to covet it, to take it as proof that I could amuse her in some way, even if all I’d said to prompt it was “That test was murder, huh?” or “Do they really expect us to run a mile in eight minutes?”

“Not good enough,” I said. I stepped off the miniature world and onto a bright red cube the size of a steamer trunk that was busily engaged in turning itself inside out. It stabilized as soon as my shoe touched it. Gravity shifted to accommodate, and behind me the “planet” collapsed into a point and vanished. I hardly noticed. Oddly, the memory of Rowena had strengthened my resolve a bit. I’d never been able to talk to her because, really, what do you say to a girl like that when you’re just one guy in a school of hundreds? There had been nothing special about me then.

Now, however, I was more than just a high school kid—I was a Walker. (Although, when you get right down to it, now I was essentially one guy in an army of a few hundred different versions of me, but thinking of it like that wasn’t conducive to my self-esteem right then.) “Tell me who you are, where you’ve taken us, and—”

She looked at me with what might have been something akin to respect but was more likely just surprise that the blushing idiot was able to form sentences. Probably the latter, because instead of actually answering me, she said, “You honestly don’t recognize the In-Between?”

“Of course I recognize—” I began, only to have her talk over me again.

“Then that renders your second question a little superfluous, doesn’t it?”

I kept talking, going right over her as she finished. “—but it’s not our In-Between.” As I said it, it became clearer to me that whatever was wrong about the In-Between was her doing. She was an unknown, and quite possibly an agent of either HEX or the Binary. But even so, I was inclined to trust her—and that really scared me. I couldn’t risk her finding out the way back to Base. The notion wasn’t likely; it took a specific formula to get back to InterWorld, and only Walkers knew it. She was clearly not a Walker. Yet, she’d traversed the In-Between. . . .

She gave me a considering glance. “You’re right. And wrong, but mostly you’re right. I’m sorry about that; I needed to make sure the Binary were off your trail.” She gave that same one-shouldered shrug and a wink. “Not to worry; it’s fixed.”

Then that purple light enveloped us again, before we could react, and that same sense of severe dislocation, worse than anything I’d ever experienced before—

And then we were home, back on the base that we all recognized. Everything was as it should be. We’d made it back to InterWorld.

Only . . .

She was with us.

THE OLD MAN IS . . .

If your principal and your sternest grandparent had a child born on the last day of summer before school starts, and that child grows up in the moment you realize you’ve been caught filching a cookie from the jar. In other words, he exists simply to remind you of all the bad things you’ve ever done, all the things you’ve ever failed at, and all the mistakes you will ever make.