Полная версия:

House of Glass

But France had a particular passion for cultural assimilation, one that has only continued to sharpen, because of the country’s devotion to the principle of laïcité, or secularity. Originally intended as a neutral, even benign principle, laïcité was instituted in 1905 with the separation of Church and state, which meant that state funding was withdrawn from religions in order to place all faiths on an equal footing and protect schools in particular from the influence of the Catholic Church. But whereas in America today the separation of Church and state means the state cannot interfere in religion, in France it means all signs of religion are banned in the public sphere, which has led to endless torturous arguments about whether Muslim women can wear headscarves or burkinis. As many modern Muslim writers have pointed out, stopping a Muslim woman from covering herself does not mean she’ll go skipping down the Croisette in a bikini like a twenty-first-century Brigitte Bardot, but rather that she’ll cloister herself off even further from French society. And to a certain extent this is what Chaya did: aware that she was not part of or welcome in French bourgeois society as she was, she stayed firmly in the Pletzl. Henri, Alex and Sara, who had the active desire to assimilate, did otherwise.

Despite what right-wing politicians today suggest, assimilation is neither simple nor the answer. There exists, allegedly, a magical sweet spot where immigrants are assimilated enough so as not to offend natives with their jarringly exotic customs, but not so assimilated that they are stealing natives’ jobs and diluting the culture of the country. Immigrants are blamed by the media and politicians for not locating this spot themselves, but no one else has ever been able to define its whereabouts either, primarily because its location shifts depending on a country’s economic situation.

By the 1930s, growing numbers of French people came to see dangers in the idea of Jews assimilating, mixing among them unrecognised. After the relaxation of naturalisation laws in 1927, right-wing newspapers and politicians spoke doomfully about immigrants taking jobs as well as Jews corrupting French society with their Bolshevik ideas and infecting the people with their strange foreign germs. When it came to assimilation, Jews couldn’t win: mix into the culture and they were condemned; stay separate and they were damned. The Jewish Question was becoming a seemingly irresolvable puzzle and it would not be long before someone offered up the Final Solution.

Today, Jewish assimilation remains controversial, and while you still hear anti-Semites warning against it, some of the most striking critics are ultra-Orthodox Jews, who use the same arguments as those advanced by the rabbinical traditionalists of the nineteenth century. (And their fidelity to those arguments is, in their eyes, the point.) According to a study carried out by the Rabbinical Centre of Europe in 2014, as many as 85 per cent of Jews in Europe are assimilated, leading one member of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate Council to lament: ‘The assimilation in the shocking numbers that we see is worse than the Holocaust we saw.’[11]

You don’t need to be assimilated, or Jewish, to find this statement repulsive. But it is true that recognisably observant Jewish people and communities are far less commonly seen in Europe today than they were at the beginning of the twentieth century. That’s not just because the Holocaust killed off so many of them[12] and many of the survivors went elsewhere (Israel, mainly), although both of those factors are certainly part of it – it’s because the successive generations have assimilated. Contrary to what Herzl and many others thought, Jewish assimilation has proven to be more than possible – it has become inevitable. As society has become increasingly secular, and Jews have made secure lives for themselves in western countries, often intermarrying with other faiths, the story of Jewish identity in the late twentieth century became a story of assimilation. Whether Jews are truly accepted depends on which Jew you ask, and how many times they’ve been accused on social media that day of being part of a Zionist conspiracy. But in terms of Jews living, working and socialising with non-Jews, this has become such a non-issue it’s almost hard to believe there was a time when it was otherwise, although that time is still very much in living memory: my grandparents would have been horrified if my father had married a non-Jewish woman, while my parents could not have cared less about the religion of my sister’s and my chosen partners. Jews have become more assimilated with each successive generation, and this is certainly borne out by my family. And for us, the path that led us here began with Henri.

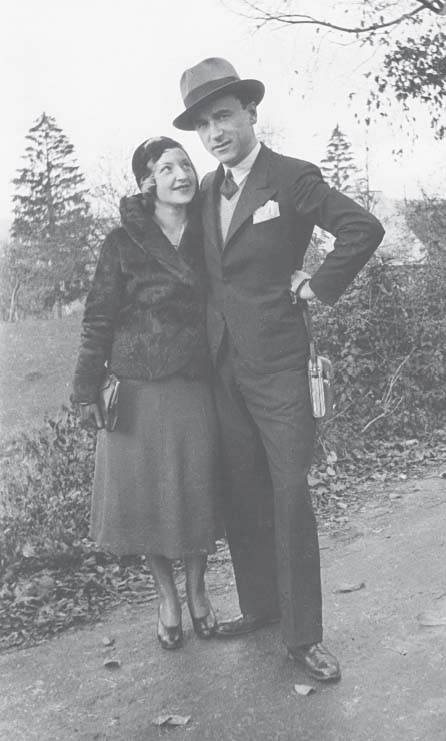

All the Glass siblings were style-conscious, thanks to Reuben’s influence, but Henri approached fashion the most methodically, because it was part of his process of becoming French. He studied how his neighbours looked and he copied them, buying three-piece suits when he could find them second-hand; double-breasted wool coats with velvet collars; starchy white shirts and silk ties, and always a hat. Henri’s style was yet another thing Alex admired about his brother, and whenever he could find the material, he made pocket handkerchiefs for him, which Henri would carefully iron and then fold neatly to stick out of his breast pocket. In everything, from his studies to his appearance, he was utterly meticulous.

He was also a very private person, so when I started to research him I originally worried he might be the lacuna in the book, as he never talked about himself.

‘Did your father leave anything that might tell me about the past – an address book, perhaps, or even old calendars?’ I asked his daughter, Danièle, the first time I interviewed her for this book in her flat in Paris.

‘Oh yes, a couple of things. Come down to the basement, I’ll show you,’ she said mildly.

I followed her down the stairs, expecting, at most, some old birthday cards, perhaps a business card or two. She unlocked the door to her building’s storage unit and there were four suitcases, each containing every receipt Henri ever got, every business transaction he conducted, every letter he received and every photo he ever took, all perfectly filed in perfect French. Henri’s careful bookkeeping was a reflection of his naturally precise nature but also of his lifelong fear that the authorities would one day call him to account, because he wasn’t truly French. As a result I probably now know more about the minutiae of his business affairs than I do about my own.

For Henri, there was one big hurdle to his assimilation into French society: his failing businesses with Jacques. By 1931 the letters from lawyers were threatening the brothers with jail, each one another kick at his dreams. A man who has the bailiffs chasing him couldn’t be a respectable Frenchman, after all. At last, one spring day, the worst letter arrived, telling him to meet the lawyer’s assistant in Gare Saint-Lazare, in la Salle des Pas Perdus – the Room of Lost Steps, the poetic French name for the hallway or waiting area in railway stations or courthouses – and she would serve him with bankruptcy papers. He dressed wearily that morning, putting on his three-piece suit, fully expecting this to be the end of his brief Parisian life. Instead, it marked the true beginning of it.

Sophie Huttner, also known as Sonia, was born in 1905 in Kopyczynce, a small city 500 kilometres to the east of Chrzanow, in what is now the Ukraine. Born into a middle-class Jewish family and exceptionally bright from a young age, she moved to Paris in 1928 to study at the Sorbonne,[13] but she really came to experience life, and she certainly succeeded in that. At the time she arranged to serve this tall, quiet man with bankruptcy papers, she’d had at least two boyfriends, a Prussian prince and a man from Barcelona, and she later hinted there had been more; Sonia had always been popular with men, and it was not hard to see why. Although not beautiful the way Sara was – Sonia’s features were earthier and less delicate – she was sexy, smart, funny and flirtatious, and she knew how to tip her head down and then look up at a man through her lashes with an irresistible little smile. As soon as Henri saw her, waiting for him in the Room of Lost Steps, he fell hopelessly in love.

Henri and Sonia shortly after they met in Paris, 1930s.

Although both were Jewish and raised in Austria-Hungary, their backgrounds were utterly different. Henri’s father had been a travelling salesman, whereas Sonia’s father was a government official. Henri had to learn French when he arrived in Paris but Sonia had grown up speaking it, because her nanny had been a dispossessed French aristocrat. Sonia didn’t even really have to work, and she lived comfortably on her family’s money for her first few years in France. But she was too smart to sit around, and she had enough drive to power the whole of Paris. She was fluent in half a dozen languages: French, Polish, German, Spanish, English, Portuguese, and she could easily switch between them in conversation. So she worked as an interpreter at several companies and as a secretary at others, and it just so happened that she was working as a secretary in a lawyer’s office when she was sent to serve papers at Gare Saint-Lazare.

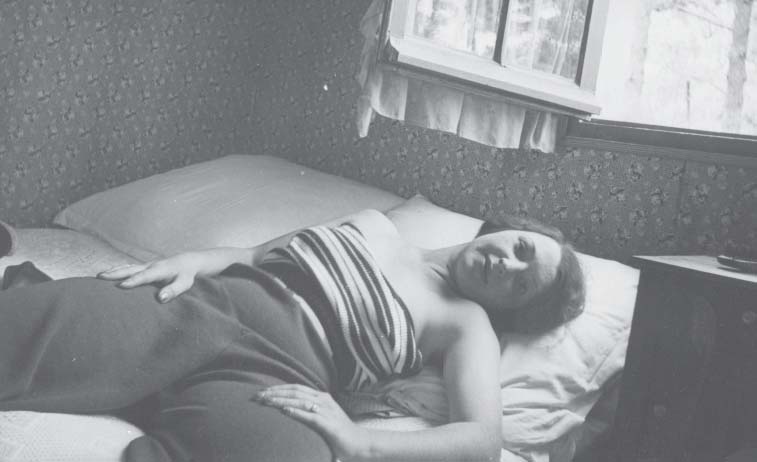

Henri was thirty-one when he met Sonia, but I could find no record of any other girlfriends in his past – no names mentioned among his letters, no teasing references by Sonia during their long lifetime together. It is entirely possible she was his first girlfriend, and he was certainly besotted by her. Henri was a keen photographer and while he took, at most, a few dozen photos of his family, he took hundreds of photos of Sonia during their courtship: here’s Sonia looking up coquettishly on a bridge; here’s Sonia in a beret, tight pencil skirt and sexy halter-neck top, plucking a leaf from a bush. Henri loved to photograph her, and Sonia loved to be photographed, posing with the ease of one who never lacked confidence about her looks. In one photo, taken in someone’s room, Sonia poses by a bed in a pair of high-waisted trousers and jacket. In the second picture, she has taken off the jacket to reveal a skimpy vest top, and she is now sitting on the bed. In the last, she has rolled the straps of her vest off her shoulder and she is lying on the bed and spreading her legs, looking into the camera with a sexuality so frank it is unnerving. I found these photos among Sonia’s possessions, twenty years after she died, and I let out a yelp when I got to the last one; you don’t expect to find eighty-year-old evidence of your great-uncle and great-aunt’s love life on an average Tuesday afternoon.

And apparently it was a very happy love life: Henri and Sonia got married on Christmas Day 1932, in Lwow, not far from where Sonia grew up, so her family could attend. Adolf Hitler would become chancellor of Germany just a few weeks later, but among the dozens of cards and letters the couple received from Sonia’s relatives and friends back home, many of whom would be killed in the Holocaust within a decade, there was only joy and hope for the future: ‘May you have a long and happy wedded life! Love, the Liebermans’; ‘Wishing joy and long life, the Zygfryd Reizs’; ‘God bless the newlyweds and their families on this happy day, the Koenigow Mlyniecs.’ And in one of Sonia’s scrapbooks I found a telegram from her new sister-in-law in France, dated 25/12/1932: ‘Bonheur bonheur bonheur de tout coeur – Sara.’

Henri didn’t have as much money as the Prussian prince, and maybe wasn’t as exciting as the man from Barcelona. But Sonia chose him because, as she explained to their daughter decades later, ‘I saw he was a good son and brother.’

Which was not to say that she was wild about his family. Chaya she quickly got the measure of when Henri took her to his mother’s flat on rue des Rosiers and she saw how much Henri longed to get some kind of independence from her. So she fashioned herself between them, stepping in whenever Chaya asked Henri to accompany her to synagogue or to do her shopping at the local kosher markets. Jacques, Sonia thought, was sweet, the sweetest of them all, only lacking in backbone. Sara bemused her with her love of fashion. But Sara told her how happy she was to have a real sister – she’d had Mindel, but Mindel had died so long ago, and she had Rose Ornstein, but Rose was really her cousin. Sonia was her sister! She’d desperately wanted a sister, and Sonia, touched, told her she felt the same.

Sonia and Sara.

Alex was a different story: Sonia and Alex loathed one another from the moment they met. Alex couldn’t believe that his idolised older brother – so tall and so handsome! – who, to his mind, could have had his pick of any Frenchwoman in Paris would choose this short, dumpy Polack. Henri had been a father figure to Alex for pretty much all of his life, ever since Reuben went off to war, and he reacted to Sonia’s arrival like a petulant child to a new stepmother. He thought she was ugly, fat and unworthy of his brother. And Sonia, who sized up Alex about as quickly as she did Chaya, saw in Alex an arrogant bully. Neither of them ever found cause to alter their first impression.

But family aside, Henri and Sonia were blissfully content newlyweds. Sonia had a much easier relationship with her past than Henri, because her childhood had been much happier. There were no tortured issues about identity, assimilation or non-assimilation for Sonia: she had grown up multilingual, so flitting between nationalities felt utterly natural to her, and her language skills were so good she was often mistaken for a native of multiple countries. And yet, even though Sonia spoke Polish and Yiddish, they almost always spoke to one another in French.

Henri, Sonia, Sara, Chaya and Jacques in Henri and Sonia’s apartment shortly after their marriage.

Soon after they were settled in their new apartment, on rue Victor-Cousin, just next to the Sorbonne, they held a housewarming supper for the Glasses, to compensate for the fact that none of them could travel to Lwow for the wedding. Henri took a photo of the evening to commemorate it, and I found the picture, eighty years later, in a small envelope on which he had written ‘famille’. Henri is the first one you notice in the photo, because he is the only one standing. In fact, he appears to be in mid-leap, as he has presumably dashed into the photo frame after having set up the camera. But even in his haste, his three-piece suit sits perfectly on him and every hair is perfectly in place. The only difference about him in this photo compared to previous ones is how happy he clearly is: he is making an unabashed open-mouthed smile and both hands are resting gently on Sonia, who is sitting in front of him. Sonia looks a little more solemn, and with her drooping shoulders and slightly raised eyebrows she looks like she’s asking the camera on the exhale, ‘Can you believe I’m stuck with this lot now?’ By contrast, Sara next to her looks absolutely delighted. She is twenty-two and a striking beauty; her confident pose, with her chin resting coquettishly on the backs of her fingers, makes her, for once, overshadow her usually more dominating sister-in-law. Chaya is seated next to her, a little in the shadows and, as usual, her eyes are going in two different directions, one looking suspiciously at the viewer, the other at Sonia. And finally there is Jacques, not quite as smartly dressed as Henri, but still stylish and very handsome, with the same finely drawn features as Sara. He is holding a French newspaper, whose front page bears a picture of Marshal Pétain, who had just been made Minister of War, and would in six years’ time become the chief of state of Vichy France. He would have more to do with the direction of Jacques’s life than Jacques could ever have imagined as he dangled the newspaper between his long thin fingers. Whereas everyone else in the photo is looking at the camera, Jacques is gazing off to the side, as if he was about to head in a different direction to the rest of them. Alex is not in the photo. Presumably he declined Henri’s invitation.

‘My father was brilliant, but he never had any success before he met my mother,’ Henri and Sonia’s daughter Danièle told me. And she was right. One of the first moves Sonia made when she and Henri got together was to help him get off the bankruptcy charge, and the second was to extricate him from his business with Jacques. Henri felt enormous guilt about leaving his brother, but, as Sonia rightly perceived, Jacques didn’t actually care that much about the business, and certainly didn’t hold it against his brother for leaving it. At last, Henri was free of the work that had caused him so much anxiety, and brought him so little satisfaction. He could simply enjoy his happy marriage with Sonia. But he now had another concern: it was 1935, he was thirty-four, and worried.

‘My time is running out,’ Sonia later recalled him saying.

But fate already had a plan for him, one more befitting to his education than running a fur and carpentry shop. Henri, or quite possibly Sonia, had recently met a man who worked at the Sorbonne Science Faculty. He said that he needed a machine that could reproduce documents quickly and cheaply, and yet no such machine existed in the whole of France. Did anyone know a man who might be able to help, perhaps one with engineering and photography experience?

Henri had finished his engineering studies a decade earlier, but he had forgotten none of it. Sonia obtained a false identity card for him on the black market so, at long last, he could get a job that utilised his education, and he went to work in the Sorbonne, like the proper Frenchman he longed to be. He could finally leave the Pletzl behind and use the skills he’d studied so hard to acquire at university. And Henri wasn’t just a good engineer, he was a truly original one. According to his American patent application, which was accepted on 12 February 1940, he made a machine ‘whereby reproductions may be made on the same scale as the original or on different scales … The prints may be made on glass, negatives, films or sensitized papers.’ In other words, he made a machine that reproduced not just documents but blueprints on microfilm and paper, and these reproductions could be to scale or – crucially – shrunk to much smaller size, making them both easy to store and illegible to anyone until Henri’s machine then reproduced them again at full size. This was to become the machine’s most important feature, and Henri was using technology that was then at the absolute cutting edge. No other machine in France could do this. Henri named his machine the Omniphot.

In less than a year, he sold versions of it to the Paris Observatory, the Army Geographic Service (now known as the Institut Géographique National) and the Paris Municipal School of Physics and Chemistry. Henri was so successful that in 1937 – just two years after despairing of the direction of his life to Sonia – he showed his Omniphot machine at the Paris fair, where it was spotted by a businessman called Marc Haenel. Monsieur Haenel instantly spotted the potential of Henri’s invention and convinced him to go into business with him to create their own company, Photosia, where they would do specialist microfilming. Henri agreed. This was to prove an extremely fortuitous meeting, and just in time, too: Henri’s machine would soon be desperately needed by the Resistance movement, and his adopted country turned out to need him at least as much as he needed it.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов