Полная версия

Полная версияThe American Revolution

The fall of Lord North’s ministry, and with it the overthrow of the personal government of George III., was now close at hand. For a long time the government had been losing favour. In the summer of 1780, the British victories in South Carolina had done something to strengthen it; yet when, in the autumn of that year, Parliament was dissolved, although the king complained that his expenses for purposes of corruption had been twice as great as ever before, the new Parliament was scarcely more favourable to the ministry than the old one. Misfortunes and perplexities crowded in the path of Lord North and his colleagues. The example of American resistance had told upon Ireland, and it was in the full tide of that agitation which is associated with the names of Flood and Grattan that the news of Cornwallis’s surrender was received. For more than a year there had been war in India, where Hyder Ali, for the moment, was carrying everything before him. France, eager to regain her lost foothold upon Hindustan, sent a strong armament thither, and insisted that England must give up all her Indian conquests except Bengal. For a moment England’s new Eastern empire tottered, and was saved only by the superhuman exertions of Warren Hastings, aided by the wonderful military genius of Sir Eyre Coote. In May, 1781, the Spaniards had taken Pensacola, thus driving the British from their last position in Florida. In February, 1782, the Spanish fleet captured Minorca, and the siege of Gibraltar, which had been kept up for nearly three years, was pressed with redoubled energy. During the winter the French recaptured St. Eustatius, and handed it over to Holland; and Grasse’s great fleet swept away all the British possessions in the West Indies, except Jamaica, Barbadoes, and Antigua. All this time the Northern League kept up its jealous watch upon British cruisers in the narrow seas, and among all the powers of Europe the government of George III. could not find a single friend.

Rodney’s victory over Grasse, April 12, 1782The maritime supremacy of England was, however, impaired but for a moment. Rodney was sent back to the West Indies, and on the 12th of April, 1782, his fleet of thirty-six ships encountered the French near the island of Sainte-Marie-Galante. The battle of eleven hours which ensued, and in which 5,000 men were killed or wounded, was one of the most tremendous contests ever witnessed upon the ocean before the time of Nelson. The French were totally defeated, and Grasse was taken prisoner, – the first French commander-in-chief, by sea or land, who had fallen into an enemy’s hands since Marshal Tallard gave up his sword to Marlborough, on the terrible day of Blenheim. France could do nothing to repair this crushing disaster. Her naval power was eliminated from the situation at a single blow; and in the course of the summer the English achieved another great success by overthrowing the Spaniards at Gibraltar, after a struggle which, for dogged tenacity, is scarcely paralleled in the annals of modern warfare. By the autumn of 1782, England, defeated in the United States, remained victorious and defiant as regarded the other parties to the war.

But these great successes came too late to save the doomed ministry of Lord North. After the surrender of Cornwallis, no one but the king thought of pursuing the war in America any further. Even the king gave up all hope of subduing the United States; but he insisted upon retaining the state of Georgia, with the cities of Charleston and New York; and he vowed that, rather than acknowledge the independence of the United States, he would abdicate the throne and retire to Hanover. Lord George Germain was dismissed from office, Sir Henry Clinton was superseded by Sir Guy Carleton, and the king began to dream of a new campaign. But his obstinacy was of no avail. During the winter and spring, General Wayne, acting under Greene’s orders, drove the British from Georgia, while at home the country squires began to go over to the opposition; and Lord North, utterly discouraged and disgusted, refused any longer to pursue a policy of which he disapproved. The baffled and beaten king, like the fox in the fable, declared that the Americans were a wretched set of knaves, and he was glad to be rid of them. The House of Commons began to talk of a vote of censure on the administration. A motion of Conway’s, petitioning the king to stop the war, was lost by only a single vote; and at last, on the 20th of March, 1782, Lord North bowed to the storm, and resigned. The two sections of the Whig party united their forces. Lord Rockingham became Prime Minister, and with him came into office Shelburne, Camden, and Grafton, as well as Fox and Conway, the Duke of Richmond, and Lord John Cavendish, staunch friends of America, all of them, whose appointment involved the recognition of the independence of the United States.

GEORGE III

Lord North observed that he had often been accused of issuing lying bulletins, but he had never told so big a lie as that with which the new ministry announced its entrance into power; for in introducing the name of each of these gentlemen, the official bulletin used the words, “His Majesty has been pleased to appoint!” It was indeed a day of bitter humiliation for George III. and the men who had been his tools.

But it was a day of happy omen for the English race, in the Old World as well as in the New. For the advent of Lord Rockingham’s ministry meant not merely the independence of the United States; it meant the downfall of the only serious danger with which English liberty has been threatened since the expulsion of the Stuarts. The personal government which George III. had sought to establish, with its wholesale corruption, its shameless violations of public law, and its attacks upon freedom of speech and of the press, became irredeemably discredited, and tottered to its fall; while the great England of William III., of Walpole, of Chatham, of the younger Pitt, of Peel, and of Gladstone was set free to pursue its noble career. Such was the priceless boon which the younger nation, by its sturdy insistence upon the principles of political justice, conferred upon the elder. The decisive battle of freedom in England, as well as in America, and in that vast colonial world for which Chatham prophesied the dominion of the future, had now been fought and won. And foremost in accomplishing this glorious work had been the lofty genius of Washington, and the steadfast valour of the men who suffered with him at Valley Forge, and whom he led to victory at Yorktown.

In the light of the foregoing narrative it distinctly appears that, while the American Revolution involved a military struggle between the governments of Great Britain and the United States, it did not imply any essential antagonism of interests or purposes between the British and American peoples. It was not a contest between Englishmen and Americans, but between two antagonistic principles of government, each of which had its advocates and opponents in both countries. It was a contest between Whig and Tory principles, and it was the temporary prevalence of Toryism in the British government that caused the political severance between the two countries. If the ideas of Walpole, or the ideas of Chatham, had continued to prevail at Westminster until the end of the eighteenth century, it is not likely that any such political severance would have occurred. The self-government of the American colonies would not have been interfered with, and such slight grievances as here and there existed might easily have been remedied by the ordinary methods of peace. The American Revolution, unlike most political revolutions, was essentially conservative in character. It was not caused by actually existing oppression, but by the determination to avoid possible oppression in future. Its object was not the acquisition of new liberties, but the preservation of old ones. The principles asserted in the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 differed in no essential respect from those that had been proclaimed five centuries earlier, in Earl Simon’s Parliament of 1265. Political liberty was not an invention of the western hemisphere; it was brought to these shores from Great Britain by our forefathers of the seventeenth century, and their children of the eighteenth naturally refused to surrender the treasure which from time immemorial they had enjoyed.

The decisive incident which in the retrospect appears to have made the Revolution inevitable, as it actually brought it upon the scene, was the Regulating Act of April, 1774, which annulled the charter of Massachusetts, and left that commonwealth to be ruled by a military governor. This atrocious measure, which was emphatically condemned by the most enlightened public sentiment in England, was the measure of a half-crazy young king, carried through a parliament in which more than a hundred members sat for rotten boroughs. It was the first violent manifestation of despotic tendency at the seat of government since 1688; and in this connection it is interesting to remember that in 1684 Charles II. had undertaken to deal with Massachusetts precisely as was attempted ninety years later by George III. In both cases the charter was annulled, and a military governor appointed; and in both cases the liberties of all the colonies were openly threatened by the tyrannical scheme. But in the earlier case the conduct of James II. at once brought on acute irritation in England, so that the evil was promptly removed. In the later case the evil was realized so much sooner and so much more acutely in the colonies than in England as to result in political separation. Instead of a general revolution, overthrowing or promptly curbing the king, there was a partial revolution, which severed the colonies from their old allegiance; but at the same time the success of this partial revolution soon ended in restraining the king. The personal government of George III. was practically ended by the election of 1784.

BUST OF WASHINGTON, CHRIST CHURCH, BOSTON

Throughout the war the Whigs of the mother country loyally sustained the principles for which the Americans were fighting, and the results of the war amply justified them. On the other hand, the Tories in America were far from agreed in approving the policy of George III. Some of them rivalled Thurlow and Germain in the heartiness with which they supported the king; but others, and in all probability a far greater number, disapproved of the king’s measures, and perceived their dangerous tendency, but could not persuade themselves to take part in breaking up the great empire which represented all that to their minds was best in civilization. History is not called upon to blame these members of the defeated party. The spirit by which they were animated is not easily distinguishable from that which inspired the victorious party in our Civil War. The expansion of English sway in the world was something to which the American colonies had in no small share contributed, and the rejoicings over Wolfe’s victory had scarcely ceased when the spectre of fratricidal strife came looming up in the horizon. An American who heartily disapproved of Grenville’s well-meaning blunder and Townshend’s malicious challenge might still believe that the situation could be rectified without the disruption of the Empire. Such was the attitude of Thomas Hutchinson, who was surely a patriot, as honest and disinterested as his adversary, Samuel Adams. The attitude of Hutchinson can be perfectly understood if we compare it with that of Falkland in the days of the Long Parliament. In the one case as in the other sound reason was on the side of the Moderates; but their fatal weakness was that they had no practical remedy to offer. Between George III. and Samuel Adams any real compromise was as impossible as between Charles I. and Pym.

It was seriously feared by many patriotic Tories, like Hutchinson, that if the political connection between the colonies and the mother country were to be severed, the new American republics would either tear themselves to pieces in petty and ignominious warfare, like the states of ancient Greece, or else would sink into the position of tools for France or Spain. The history of the thirty years after Yorktown showed that these were not imaginary dangers. The drift toward anarchy, from which we began to be rescued in 1787, was unmistakable; and after 1793 the determination of France to make a tool of the United States became for some years a disturbing and demoralizing element in the political situation. But as we look at these events retrospectively, the conclusion to which we are driven is just opposite to that which was entertained by the Tories. Dread of impending anarchy brought into existence our Federal Constitution in 1787, and nothing short of that would have done it. But for the acute distress entailed by the lack of any stronger government than the Continental Congress, the American people would have been no more willing to enter into a strict Federal Union in 1787 than they had been in 1754. Instead of bringing anarchy, the separation from Great Britain, by threatening anarchy, brought more perfect union. In order that American problems should be worked out successfully, independence was necessary.

It is to be regretted that the attainment of that independence must needs have been surrounded with the bitter memories inseparable from warfare. In such a political atmosphere as that of the ancient Greek world it need not have been so. The Greek colony, save in two or three exceptional cases, enjoyed complete autonomy. Corinth did not undertake to legislate for Syracuse; but the Syracusan did not therefore cease to regard Corinthians as his fellow-countrymen. The conceptions of allegiance and territorial sovereignty, which grew to maturity under the feudal system, made such relations between colony and mother state impossible in the eighteenth century. Autonomy could not be taken for granted, but must be won with the sword.

But while, under the circumstances, a war was inevitable, it is only gross ignorance of history that would find in such a war any justification for lack of cordiality between the people of the United Kingdom and the people of the United States. As already observed, it was not a war between the two peoples, but between two principles. The principle of statecraft against which Washington fought no longer exists among either British or Americans; it is as extinct as the dinosaurs. In all good work that nations can do in the world, the British people are our best allies; and one of the most encouraging symptoms of the advancement of civilization in recent years is the fact that a grave question, which in earlier times and between other nations would doubtless have led to bloodshed, has been amicably adjusted by arbitration. The memory of what was accomplished in 1872 at Geneva is a prouder memory than Saratoga or Yorktown. From such an auspicious beginning, it is not unlikely that a system may soon be developed whereby all international questions that can arise among English-speaking people shall admit of settlement by peaceable discussion. It would be one of the most notable things ever done for the welfare of mankind, and it is hoped that the closing years of our century may be made forever illustrious by such an achievement.

Transcriptions

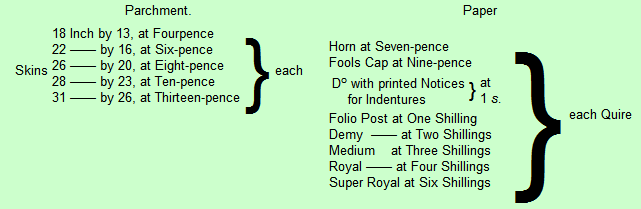

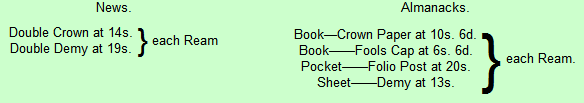

Transcription of the text of paper pricesSTAMP-OFFICE, Lincoln’s-Inn, 1765A TABLE

Of the Prices of Parchment and Paper for the Service of America.

Paper for Printing

GENTLEMEN,

The committees of correspondence of this and several of the neighbouring towns, having taken into consideration the vast importance of withholding from the troops now here, labour, straw, timber, slitwork, boards, and in short every article excepting provisions necessary for their subsistance; and being under a necessity from their conduct of considering them as real enemies, we are fully satisfied that it is our bounden duty to withhold from them everything but what meer humanity requires; and therefore we must beg your close and serious attention to the inclosed resolves which were passed unanimously; and as unanimity in all our measures in this day of severe trial, is of the utmost consequence, we do earnestly recommend your co-operation in this measure, as conducive to the good of the whole.

We are,Your Friends and Fellow Countrymen,Signed by Order of the joint Committee,William Cooper, ClerkTranscription of the text of King’s ProclamationBy the KING,A PROCLAMATIONFor suppressing Rebellion and SeditionGEORGE R.

Whereas many of Our Subjects in divers Parts of Our Colonies and Plantations in North America, misled by dangerous and ill-designing Men, and forgetting the Allegiance which they owe to the Power that has protected and sustained them, after various disorderly Acts committed in Disturbance of the Publick Peace, to the Obstruction of lawful Commerce, and to the Oppression of Our loyal Subjects carrying on the same, have at length proceeded to an open and avowed Rebellion, by arraying themselves in hostile Manner to withstand the Execution of the Law, and traitorously preparing, ordering, and levying War against Us. And whereas there is Reason to apprehend that such Rebellion hath been much promoted and encouraged by the traitorous Correspondence, Counsels, and Comfort of divers wicked and desperate Persons within this Realm: To the End therefore that none of Our Subjects may neglect or violate their Duty through Ignorance thereof, or through any Doubt of the Protection which the Law will afford to their Loyalty and Zeal; We have thought fit, by and with the Advice of Our Privy Council, to issue this Our Royal Proclamation, hereby declaring that not only all Our Officers Civil and Military are obliged to exert their utmost Endeavours to suppress such Rebellion, and to bring the Traitors to Justice; but that all Our Subjects of this Realm and the Dominions thereunto belonging are bound by Law to be aiding and assisting in the Suppression of such Rebellion, and to disclose and make known all traitorous Conspiracies and Attempts against Us, Our Crown and Dignity; And We do accordingly strictly charge and command all Our Officers as well Civil as Military, and all other Our obedient and loyal Subjects, to use their utmost Endeavours to withstand and suppress such Rebellion, and to disclose and make known all Treasons and traitorous Conspiracies which they shall know to be against Us, Our Crown and Dignity; and for that Purpose, that they transmit to One of Our Principal Secretaries of State, or other proper Officer, due and full Information of all Persons who shall be found carrying on Correspondence with, or in any Manner or Degree aiding or abetting the Persons now in open Arms and Rebellion against Our Government within any of Our Colonies and Plantations in North America, in order to bring to condign Punishment the Authors, Perpetrators, and Abettors of such traitorous Designs.

Given at Our Court at St. James’s, the Twenty-third day of August, One thousand seven hundred and seventy-five, in the Fifteenth Year of Our Reign.

God save the KingLONDON:Printed by Charles Eyre and William Strahan, Printers to theKing’s most Excellent Majesty. 1775Transcription of A Page from “COMMON SENSE”The Sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ’Tis not the affair of a City, a County, a Province or a Kingdom; but of a Continent – of at least one eight part of the habitable Globe. ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected even to the end of time by the proceedings now. Now Is the seed-time of Continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now, will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

By referring the matter from argument to arms, a new æra for politics is struck – a new method of thinking hath arisen. All plans, proposals, &c. prior to the 19th of April, i. e. to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacks of the last year; which tho’ proper then, are superseded and useless now. Whatever was advanced by the advocates on either side of the question then, terminated in one and the same point, viz. a union with Great-Britain; the only difference between the parties, was the method of effecting it; the one proposing force, the other friendship: but it hath so far happened that the first hath failed, and the second hath withdrawn her influence.

As much hath been said of the advantages of reconciliation, which like an agreeable dream, hath passed away, and left us as we were, it is but right that we should examine the contrary side of the argument, and enquire into some of the many material injuries which these Colonies sustain, and always will sustain, by being connected with, and dependant on Great-Britain. – To examine that connection and dependance, on the principles of nature and common sense, to see what we have to trust to if separated, and what we are to expect if dependant.

Transcription of the text of Clark’s LetterColonel Clarks Compliments to Mr Hamilton and begs leave to inform him that Col. Clark will not agree to any other Terms than that of Mr Hamilton’s Surendering himself and Garrison, Prisoners at Discretion.

If Mr Hamilton is Desirous of a Conferance with Col. Clark he will meet him at the Church with Captn Helms.

Feb 24th 1779 Geo Clark1

See my Critical Period of American History, chap. i.

2

In his account of the American Revolution, Mr. Lecky inclines to the Tory side, but he is eminently fair and candid.

3

On the pedestal of this statue, which stands in front of the North Bridge at Concord, is engraved the following quotation from Emerson’s “Concord Hymn: " —

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,Here once the embattled farmers stood,And fired the shot heard round the world.The poet’s grandfather, Rev. William Emerson, watched the fight from a window of the Old Manse.

4

It was in this church on March 23, 1775, that Patrick Henry made the famous speech in which he said, “It is too late to retire from the contest. There is no retreat but in submission and slavery. The war is inevitable, and let it come! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death.”

5

In the letter, of which a facsimile is here given, Allen gives the date of the capture of Ticonderoga as the 11th, but a minute survey of the contemporary newspaper and other sources of information makes it clear that this must be a slip of the pen. In his personal “Narrative,” Allen gives the date correctly as the 10th.

6

This sketch was made on the spot for Lord Rawdon, who was then on Gage’s staff. The spire in the foreground is that of the Old West Church, where Jonathan Mayhew preached; it stood on the site since occupied by Dr. Bartol’s church on Cambridge Street, now a branch of the Boston Public Library. Its position in the picture shows that the sketcher stood on Beacon Hill, 138 feet above the water. The first hill to the right of the spire, on the further side of the river, is Bunker Hill, 110 feet high. The summit of Breed’s Hill, 62 feet high, where Prescott’s redoubt stood, is nearly hidden by the flames of burning Charlestown. At a sale of the effects of the Marquis of Hastings, descendant of Lord Rawdon, this sketch was bought by my friend Dr. Thomas Addis Emmet.